The modern-day buccaneers who plunder Cornwall’s treasure

Bad housing developments are threatening Cornwall’s landscape, culture, and its sense of community – themes which have inspired Orlando Kimber’s new novel, ‘Fightback’

Cornwall is like a boat on the ocean: remote, independent and self-sufficient, but kept from conceit in her beauty by the Atlantic storms. My relationship with this remarkable country began when I left school and wanted to escape from London. A friend introduced me to a family who needed cheap labour for their flower nursery near Truro. We met on a cold, grey February afternoon at the Stanhope Arms on Gloucester Road and made the deal. I would stay in the semi-derelict Georgian Manor House that was the family home, and help to grow the fuchsias they cultivated in long, humid, opaque greenhouses.

I arrived a few days later in the driving rain, and this is how it stayed for a further six weeks. Yet this was to become one of the hottest summers of the 20th century, and I’d ended up in one of the best places in the country to enjoy it. The more I came to know the local people, the land, the sea, and the local produce, the more I felt I belonged.

Music has always been a great love, and while in Cornwall, I recorded some guitar pieces at a tiny studio, in a damp cold converted barn at Roche, heated by a three-bar electric fire. Friends made encouraging noises about the recording, so the guitar and I returned to the bright lights of London in January to seek our fortune. This ensured that my latest change of location would again be in unremitting rain. I was lucky enough to land a job with EMI film music, and began working in some of the best studios in the world, with wonderfully creative composers, and the cream of session musicians.

I went on to produce and write music for film and tv, but by 28 I was married with a child. As family life made its demands, business sucked me into its whirlpool. I continued to write music and words late at night, at weekends, or on the long commute between home and office.

As my involvement with enterprise deepened, I studied what makes good companies helpful and what makes bad companies harmful. Working as an advisor to many clients, I saw examples of brilliant management and shocking behaviour. Experience taught me that ethics are the foundation of a good business. When a corporation takes on employees or assets (such as property, land or the right to draw on a resource) they, at the very least, acknowledge a duty of care.

Some deliberately cultivate a sense of shared purpose, which inevitably results in high levels of motivation and general contentment. The ideal is ethical governance: a deep respect for staff, suppliers and customers, transparent decision-making based on good evidence, and actions aimed at genuinely sustainable outcomes. The “bad” are almost entirely selfish. It’s impossible for staff to feel “we’re in this together” when the directors clearly have the attitude of “every one for themselves” while using “survival of the fittest” as a pretext.

The highlight of my business career came when I built up a very successful operation in Qatar for a British company. Everything was wonderful until the parent company started behaving strangely … I’d recognised the poor calibre of the senior management before I’d left Britain, but it was still a surprise when they mistreated me.

My partner, Boo, and I moved back from the arid heat of the Middle East to the damp chill of a British winter. She has strong family roots in Cornwall, so we chose this as a good place to take stock after our recent adventures. However, Cornwall has one of the lowest economic outputs per capita in Europe, and the first piece I read in a local newspaper – before they went online – was the announcement of government support for enterprise in the region. This was so meagre that the total fund was half the turnover of the company I’d created.

There were vast changes since my time at the fuchsia nursery, and I felt a growing unease. I saw the same poisonous practices of pandering to tourism one sees worldwide, and the negative effect this has on the local people. Though Cornwall has an undeniable history of piracy and wrecking from ancient times, it seemed to me the modern buccaneers are those business owners who prey on the assets of Cornwall. They neither live there nor produce anything useful for the region.

Bad development destroys our sense of togetherness and identity, together with the heritage and culture that’s taken millennia to develop

What had not changed was the warmth, goodness and simplicity of those who inhabit and genuinely love Cornwall. They too had an intimate relationship with the sea, the land and, although often unspoken, the heritage and culture. This is a country which King Athelstan failed to possess when he sought to centralise government in the 11th century. He drew the line at Exeter. Even now, the magic of an even earlier age – King Arthur’s Britain – still breathes softly in a few remote and unmarked spots.

Unsurprisingly, I got involved in local and national groups, seeking to defend and conserve the environment and communities. I wrote short pieces on ethics in politics, business, culture, the home and relationships, and found I could influence others to action. As groups, we could raise awareness of problems and potential solutions, but in doing so we exposed a fatal flaw: genuine political discourse between citizens and government barely exists in Cornwall, or in Britain as a whole.

A year later, a doctor prescribed a medication for Boo’s skin cancer and it disabled her. Severely. Overnight, I became a carer. My time was no longer my own, and it cut me off from my sources of employment. As Boo’s health deteriorated, she suggested I write a novel, as all the inspiration I needed was on my doorstep.

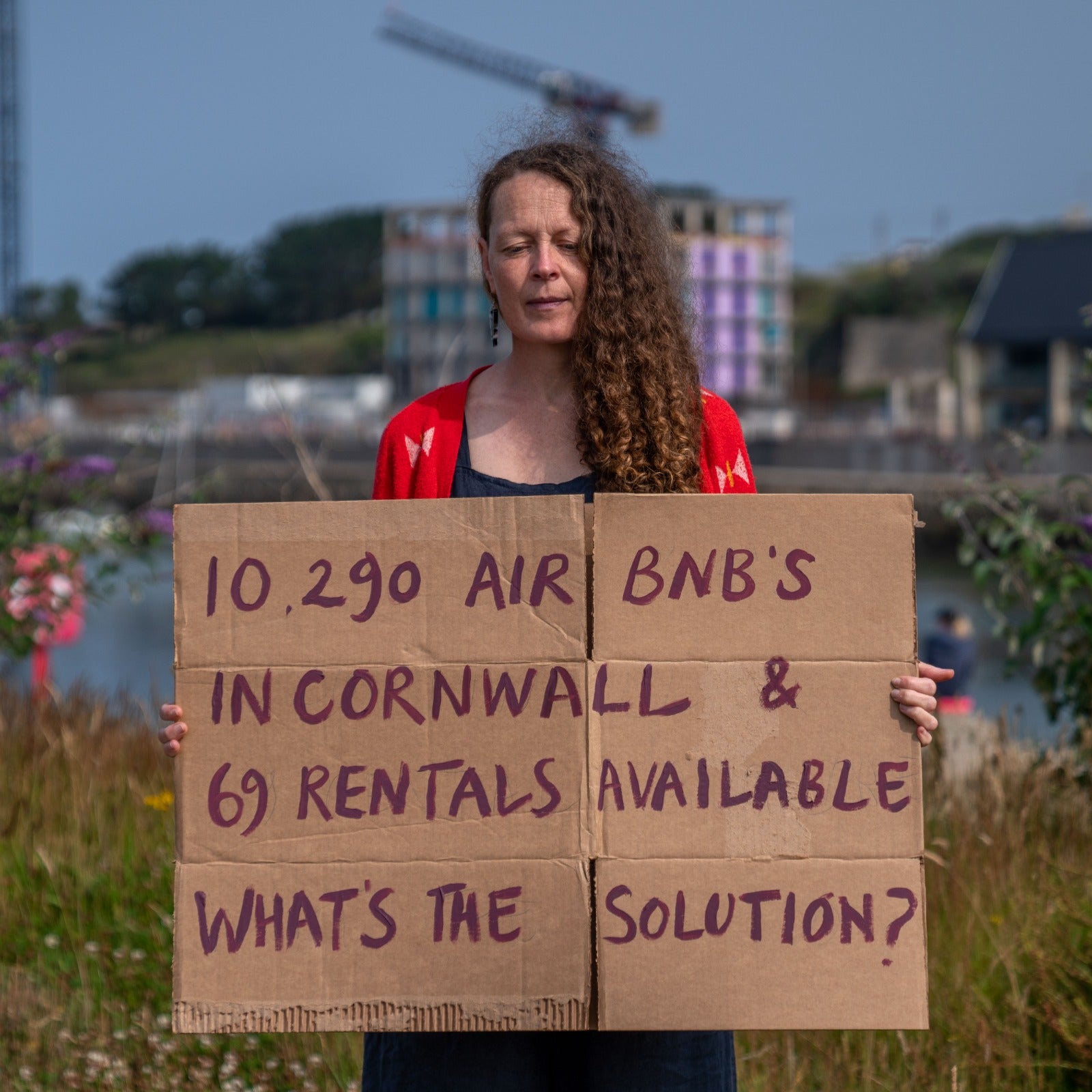

Over the past 50 years, Cornwall has had the second highest number of major residential planning applications (developments of more than 10 properties). Only Cumbria has had greater demand. Population growth in Cornwall has declined since the 1980s, so who is buying all these houses? The answer is in another statistic: the region with the highest number of properties with no usual resident is, you’ve guessed it, Cornwall. The purchases are for second homes or holiday lets.

Bad development destroys our sense of togetherness and identity, together with the heritage and culture that’s taken millennia to develop. In Cornwall, there are still countless tracks, roads, stone crosses, meadows and hamlets that bear clues to our provenance.

Cement covers all such traces and separates us from all that is fine and unique in the landscape. We still have each other, but we lose the physical distinctions – the old chapel, the narrow lane overhung with apple-tree beech leaves in spring, the granite stile – that make our places special. Once a green field is gone, it’s gone forever.

I wanted my novel to be modern, interesting and fun, but also to acknowledge how important our sense of place is to society. I needed to show that the landscape, communities and unique culture of Cornwall are being systematically destroyed. This is a loss to us all, as millions choose to take a holiday here every year.

It’s also a symptom of a national disaster unfolding in slow motion; the concreting of Britain, and its sale to the highest bidder. Most of the new owners don’t live in the local area, and many don’t even live in the UK. The loss of identity and green spaces in Cornwall is not unique – it’s a challenge that afflicts us all – but it doesn’t have to be this way.

Obviously, not all development is wrong, but we need criteria for what qualifies as suitable. For instance, there’s a specific need for protection of the landscape in Cornwall, and yet there is currently no way to assert this. An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) no longer has any statutory weight in the real world. This led me to a theme for the book of “unwanted development” – but a powerful story is about consequences, not causes. It’s about how people respond to a crisis.

Carl Webster, a house painter, grew up in St. Austell. He lives in nearby Charlestown, with his partner and two daughters, aged seven and three. “We’re very happy to live where we do, but we’ve seen a lot of changes in the past seven years. There are so many new builds thrown up around here. We’re lucky, because we bought one of the few affordable homes, which means buying at a market discount, not low cost.

“Most of the houses on our estate went for the full market price, and 50 per cent are second homes. The owners turn these into either short-term rentals, or Airbnb throughout the summer. This damages the feeling of community on the estate. My big worry is how my daughters will afford a house when they’re grown.”

My theme broadened to “community”, but I still needed a central character, so I plundered my experiences as a teenager. However, by the time we join the protagonist, Sam Alder, he’s 28 and doing his best to extend his youth as long as possible. He’s having a great time surfing and hanging out with his tribe while making a go of his carpentry workshop. He’s so sure of himself that he’s barely aware of other people’s feelings and needs.

Then something happens which threatens not only his way of life, but that of the entire community and … Sam has to follow a thread to confront “the monster” in its lair. In doing so, he must not only uncover who is behind the threat, but the source of their strength.

We live in such “interesting” times. The social contract by which government should rule by consent of the people for the common good appears to be confused. A well-known government minister once told me that “the economy needs growth” and “we have no choice”; but as Gandhi said: “True economics never militates against the highest ethical standard.”

Government empowers developers, who feel no responsibility other than to turn a profit for themselves. They then depart, leaving the community dispossessed. While the maintenance of general prosperity for one and all is a noble aim of government, surely it should not speculate in property at the cost of its citizens?

The pollution by noise and light of our quiet and remote places, the poisoning of the air by waste incinerators, and the spoiling of our rivers and coast continues as you read this. The corporations that build expensive little boxes as houses on Cornwall’s green fields are merely exercising the right given them by the government they lobby. Similarly, the companies which use the streams as sewers, and local authorities who market ancient fields as a mere commodity, are doing so because they can.

Ultimately, the message of my novel is that the land belongs to those who live there. We need to protect our coastline, our landscapes and, particularly, our communities. We need continuous investment into a practical plan that strengthens Cornwall, and works for everyone who lives there.

The “development” of houses in Cornwall currently serves neither the people who live there, the environment, nor the local economy. We are all at a crossroads. Are we going to create a society that allows ordinary people on low incomes to have a decent life and support future generations? Or will we continue to divide society into life-style and life-struggle?

If we act together we can make a difference, but we need a representative system that is fiercely protective of the interests of local people, and rigorously honest. Unlike films and novels, we cannot leave salvation to lone individuals like Sam Alder, struggling against seemingly insuperable odds.

‘Fightback’ is published by Arthur & Moose (A&M) Publishing, and is available now as both paperback and ebook

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks