Facebook Australia was a defining moment for the web, journalism and democratic sovereignty

Facebook’s decision to withdraw services from Australia led to worldwide condemnation. But behind the florid rhetoric lies a dramatic story involving cash, corruption and a revenge drama of epic proportions, writes Chris Horrie

Bald mountain in Blaine County Idaho provides one of the best – if not the best – natural runs for skiing anywhere in the world. The lure of the great outdoors, the thrill of the descent, the dazzling sunsets and crystal Rocky Mountain air is enhanced by a certain bohemian chic. The nearby resort of Sun Valley was once the home of Ernest Hemingway and hero journalist Martha Gellhorn, who lived there rent-free in the town’s ski lodge in the 1930s on the rare occasions when they were not in some war zone or other dangerous spot.

You or I might, therefore, imagine Martha Gellhorn spinning in her proverbial grave when in July 2016 Murdoch met the head of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, in his private Sun Valley villa to see if they could end the cold war over control of the global news industry which had been escalating between them for a decade.

Murdoch and Zuckerberg were not so much unlikely as wildly inappropriate bedfellows. The former had reduced journalism to a type of “criminal enterprise”, as a leading British parliamentarian put it, brought to a new low in the estimation of the public everywhere; the latter had ripped the financial guts out of the entire news industry, meaning that large parts of the press, especially at its grassroots was in danger of disappearing entirely.

The meeting did not go well. The immediate cause of friction was a change to the secret algorithm Facebook used to select stories from news websites around the world, a huge proportion of which in the US, UK and Australia at least, were owned and operated by Murdoch. Facebook paid nothing for this content but was starting to earn billions of dollars each year from advertisers trying to reach users persuaded to stay on the site by the news material.

Murdoch’s team had taken to calling this business model a form of “piracy” or even “theft”. But Zuckerberg argued that Murdoch couldn’t really complain. His companies made money too – indirectly from the additional audience brought to his titles via their daily hook up with Facebook. Without the trap door of Facebook, users would have to hunt around the internet to find his titles. With Facebook functioning as a sort of shopping mall of internet content (and definitely not a publisher), everyone who had a place in that shopping mall was a winner.

Now Zuckerberg had changed the algorithm, affecting the type and source of content that would be prominent in Facebook’s news feed; the equivalent, potentially, of being taken out of the prime supermarket position in the entrance to the mall and buried away amid the tumbleweed on the third floor up the escalator, next to the toilets and the seldom-visited local charity shop.

It was not just that Murdoch’s content was being downgraded, even if that was the case. It was that Zuckerberg had made the change without warning and without negotiating. Murdoch’s team demanded more control over the position of their content on Facebook, expressed as “consultation” over any changes to the algorithm. Murdoch’s position at that time was one of weakness. He had to concede that Zuckerberg could keep all or most of the ever-growing revenues he was getting, as Murdoch saw it, from pointing to content on his news outlets so long as Facebook continued to function as a free and ubiquitous distribution system for those outlets.

For once Murdoch was unable to stack the cards in advance in a business negotiation. But he was not entirely empty-handed. Where money would not work Murdoch turned to politics, as he had often done in the past, and especially the politics of personal vilification. He would aim for regulatory and legislative changes which would hamper his rival Facebook and give him the initiative. The negotiations went public in the United States.

Murdoch’s Fox News channel began to emit a steady drumbeat of hostile Facebook coverage designed to make the company a pariah, weakening its political position and making it vulnerable to threats of disbandment. Zuckerberg was monstered as a heartless “globalist” elitist who made his money distributing horrific videos of rapes, murders and suicides while displaying a cavalier attitude towards child protection. The campaign of coverage was relentless with any attempt by Facebook to remove content of this sort or provide protection turned into admission of the website’s complicity.

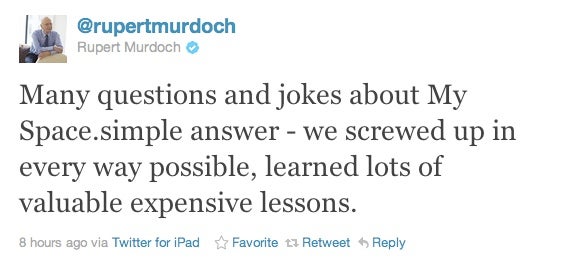

Murdoch knew first-hand how devastating this sort of publicity could be. The fact appears to have disappeared down the same memory hole as Murdoch’s role in the phone hacking scandal, but the reality is that it was Murdoch, and not Zuckerberg, who was the first entrant into the global social media, friending and content-sharing business. In 2005 Murdoch bought MySpace –the first truly global social media website – paying $580 million to acquire what was then the largest website in the world with more users even than Google.

MySpace was Murdoch’s prototype version of Facebook and it was fraught with the same problems of unintentionally – or carelessly – distributing inappropriate material and failing to protect vulnerable users, especially children, from harm. The problems with MySpace were if anything proportionately worse than with Facebook, and the resistance to provide effective protection for users (a major operating cost for sites like this) appeared to be greater.

An inquiry in the US responding to parental fears that their children were being stalked by sexual predators on the site found that MySpace had allowed approximately 90,000 registered sex offenders to become members over a period of two years in just one state, Connecticut. The site was found to have done little to prevent “an onslaught of sexual predators targeting younger social-networking clients”.

The investigation found that MySpace’s age verification was ineffective (at that time) and children as young as 12 could link through to pornography or interact on sexual themes with adults. There had been seven incidents of sexual assault in the state directly linked to MySpace. There were other problems including self-harm and even suicide attributed to cyber bullying permitted by the site and the phenomena of teens advertising house parties, unfiltered by the site, attracting hundreds of riotous teenagers. One teenage girl was shot dead at a violent MySpace organised party in Seattle.

In 2017 Facebook revealed that a Russian group had paid them $100,000 for 3,000 political adverts aimed at voters

Ironically, Facebook was launched as a safe and non-sleazy alternative to MySpace. Zuckerberg’s site was an immediate success partly because of its better (if still imperfect) privacy protection policies and its relatively simple, unfussy design. MySpace in contrast had been heavily laden with annoying pop-up ads for Murdoch content and paid-for advertising. The site was insecure and users sometimes found themselves drowning in spam, or that they had become victims of identify fraud. In 2008 more than half a million private MySpace user pictures were stolen from the site and made available to hackers on a dark web download site.

Murdoch initially dismissed Facebook as a passing fad: “Flavour of the month,” as he put it. Even when Facebook overtook MySpace in 2008 with 123.9 million users against 114.6 million, Murdoch continued to invest in MySpace for another four years. In 2012 Murdoch admitted he had got it wrong. He sold MySpace for $35 million, losing $545 million on the sale price. MySpace still operates under a slightly different name, under new management and with an entirely different ethos.

In the four years after his MySpace debacle Murdoch was consumed by the backwash of the News of the World phone hacking scandal which, at one point, looked like dragging down his entire empire. Worse still he appeared to be without a digital strategy, flailing around with tentative and gimmicky new media ventures which went nowhere.

Commentators began to say that Murdoch understood newspapers and rolling television news; but the internet was different. Murdoch could not operate there because he could not see how he could monopolise the medium. He thus re-organised the empire, divesting himself of the entertainment and movie-making wing of 21st Century Fox, suspecting it would no longer be able to reap profits in competition with a number of cheap start-up streaming and distribution companies.

By 2016 Murdoch had completed his corporate re-jig, was concentrating all his efforts on Fox News and American politics and was ready to apply pressure to Facebook, now effectively his only serious long-term private sector competitor in the battle for domination of the internet. The result was the now famous alliance between the audience for Fox News and the political base which was to propel Donald Trump to the US presidency.

In 2016 Hilary Clinton’s Democrats had already factored in the Fox News audience as a large but not decisive segment of the US electorate – an alliance of poorly educated sexists, racists, homophobes – and calculated they would still win a majority against Trump, as the polls indicated. The Democrats were astonished when Trump won, and came to believe his victory was largely the result of Russian state intelligence propagandists expertly targeting key groups of swing voters using Facebook and its lightly supervised news feeds.

The political pressure on Zuckerberg became intense. And it came from both sides of the political aisle. In September 2017 Facebook, under pressure from a Senate investigation, revealed that a Russian group had paid them $100,000 for 3,000 political adverts aimed at voters in the 2016 presidential election. In October of the same year researchers traced six Facebook accounts to Russian propaganda agents who had managed to share damaging and untrue stories about Hilary Clinton 340 million times. Zuckerberg’s Facebook and not Murdoch’s Fox News was seen as the cause of Trump’s victory and calamitous presidency.

Zuckerberg was being attacked by Fox, Trump and the Republicans for supposedly systematic anti-conservative bias among his archetypal super-liberal silicon valley workforce. The politics became still more difficult when leaks from Facebook headquarters indicated bias against the political right was widespread among teams charged with keeping Facebook’s content politically neutral. But the hypocrisy was once again palpable. Murdoch’s news operations were a by-word for bias and even outright propaganda in every country where he was a major player.

Zuckerberg was nevertheless on the horns of a dilemma. If he moved to remove “fake news” or political extremism such as racism from his website he would be accused of political bias and editorial control as a sort of creepy, vaguely weird self-appointed Big Brother. But if he maintained his original stance of “content neutrality”, allowing anyone to post anything regardless of veracity, he would be providing an open door for foreign powers to create an echo-chamber designed to whip carefully selected segments of the US population into a destructive frenzy.

The most widely canvassed solution to this problem was that Facebook should maintain “content neutrality” but only among a group of verified or certified, reliable sources of news. Murdoch saw his chance and grabbed the initiative. In January 2018, two years after the tempestuous Sun Valley meeting with Zuckerberg, Murdoch issued a scathing statement which castigated Facebook and Google for “stealing” content from legitimate news organisations, such as his own, and for “popularising scurrilous news sources through algorithms that are profitable for these platforms but inherently unreliable”.

Murdoch was moving on, too, from his demand for some control over Facebook’s algorithm. He now wanted hard cash payments in the form of a share of Facebook’s advertising revenues. And he was ready to use the political muscle provided by his newspapers and TV channels to force Zuckerberg to pay up.

It was time, Murdoch said in his statement, for a new approach to the economics of digital news. Facebook should pay directly for the right to link to “trusted publishers” to fund verified “quality journalism” which in turn would squeeze out “fake news” in all of its many guises.

Murdoch’s definition of a “trusted publisher” was that of a company, such as his own, which was able to charge “carriage fees” for inclusion on a pay TV system. The argument was that nobody would pay for fake news, at least not for very long. It just so happened that the news websites such as Sky News and Fox News, linking to his newspaper websites, would qualify for payment from Facebook.

But rivals including public service broadcasters like the BBC or news organisations which did not produce rolling cable or satellite TV channels, such as Murdoch’s great rival the New York Times, would get, nothing. Analysts concluded that Murdoch’s proposal, if adopted, would entitle him to claw back perhaps half of Facebook’s advertising revenues – producing around $90 billion a year and growing, with the other half shared between four or five rival cable news channels and their associated websites.

Facebook, Google and other social media companies could only be compelled to make such payments by regulators, and that would require the intervention in the US of Trump and the Republican Party. Trump’s defeat in the US election was doubtless a set-back for Murdoch, but he had another card to play: His former homeland of Australia.

In May 2019, a few months before Trump’s defeat, Scott Morrison, leader of the Liberal party, Australia’s rough equivalent of the US Republicans, won that country’s general election to the surprise of almost everyone. It was the third in a trio of “populist” electoral upsets in countries where Murdoch dominated the news media: Trump in the US, Brexit in the UK and now the Liberals in Australia. Morrison described the result as “a miracle”.

Facebook Australia was turned back on again and Zuckerberg will have to negotiate with Murdoch, entirely on Murdoch’s terms and backed by a law enacted by a government he recently helped

The defeated Labour Party, favourite in the polls, pointed to a campaign of vilification of their candidate, of rabid anti-immigrant propaganda and climate-change scepticism amounting, critics said, to “climate denial”. The alliance between Murdoch and Morrison had been so close that even former Liberal party leader Malcolm Turnbull complained that under Scott Morrison a “full merger” between his party and Murdoch media had taken place. Murdoch’s spokespeople, for their part, claim that this was just sour grapes. The Labour Party had lost, they said, because they were useless.

Co-incidence or not Morrison was ready to regulate Facebook and Google in Australia, forcing them to pay “the media” for the use of news content. Using Murdoch’s “carriage fee” definition, that might mean as much as 70 per cent of Facebook and Google’s advertising revenue would henceforth be handed over to Murdoch under the terms of a new law proposed by Morrison. This would have enormous impact in Australia where almost 75 per cent of total advertising revenue last year went to Google and Facebook according to Australian competition authorities.

Naturally, Murdoch welcomed the proposed new law as a way of funding “responsible journalism”, and even of strengthening democracy. Many bought into this narrative, including news organisations and media outlets which might expect to get their own, more modest shares of advertising revenues, and from journalists’ unions, which hoped that the money provided by Facebook would result in more jobs.

But there was no guarantee in the Murdoch plan that this would happen. He would be free to use the billions to invest in his company more generally – in acquisitions to further consolidate his near-monopoly position perhaps. Previous pledges given to governments to invest in journalism and editorial independence when, for example, monopoly restrictions were lifted to allow him to gain control of The Times in London, proved to be worth less than the paper they were written on. The first draft of the proposed law would have excluded Australia’s equivalent of the BBC from receiving payment.

Facebook’s image was so tarnished that many went along with the unusual idea that Rupert Murdoch, the political power-broking mastermind of the MySpace and phone hacking disasters, was the best guarantor of the future of public service journalism and the person most suited to safeguard the financial basis of the industry. One dissenting voice was that of Sydney-based billionaire software developer Mike Canon-Brookes. He took to Twitter to denounce the proposed law as “a shakedown”.

Google’s Australian branch gave into the pressure right away, negotiating undisclosed payments to Murdoch and other Australian publishers, rumoured to be around $20 million a year, to avoid the likely higher payments which could be imposed by way of compulsory arbitration under the terms of the proposed law. Facebook, in contrast, “went nuclear” as one commentator put it, by closing down Facebook in Australia rather than handing over cash to Murdoch.

Zuckerberg’s plan appears to have been that Australian voters, finding that their Facebook accounts no longer worked, would pressure the Morrison government to abandon the proposed law.

The tactic was a PR disaster. Murdoch’s spokespeople described Facebook’s withdrawal as “an act of war” by a private company against a sovereign nation. For once politicians and publishers on the centre and left found themselves on the same side as Murdoch and his outlets: he had united an unbeatable coalition of self-interest and naive optimism across the political spectrum.

Zuckerberg suffered a humiliating defeat. Facebook Australia was turned back on again and Zuckerberg will have to negotiate with Murdoch, entirely on Murdoch’s terms and backed by a law enacted by a government he has recently helped into power against all odds. Most importantly of all Murdoch’s victory in Australia has created a legal precedent that will soon begin to roll through the courts in every significant media market in the world.

In a long career Mark Zuckerberg is just about the only significant media player who inflicted defeat on Murdoch. At the dawn of the social media age it was Facebook which put paid to MySpace – Murdoch’s attempt to dominate the new media just as effectively as he dominated the old.

The tables have turned once again. For Murdoch, revenge has turned out to be a dish served cold – and profitable on an almost unimaginable scale.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks