How the ‘Pampas Bull’ conquered Silverstone for Ferrari’s first ever F1 victory

Formula One’s most successful team are returning to the top after years in the wilderness. Mick O’Hare looks back at the stocky farm worker who secured the scarlet cars’ first win

When Max Verstappen so very controversially took the chequered flag in Abu Dhabi last year to win his first Formula 1 world championship, change was in the air. The arguments will rage long and hard about whether Verstappen – through no skulduggery on his part – stole the title from Lewis Hamilton, as the rule book was tested to its limit and possibly beyond. But a new kid was on the block whether the old guard at Hamilton’s Mercedes team liked it or not.

And whatever the rights and wrongs of the decisions that gifted Verstappen his first title, there is no doubt that this 2022 season, the Red Bull driver and his teammate, Sergio Perez, have been quick out of the blocks, winning seven of the nine races so far. But they have been pushed all the way by Ferrari’s Charles Leclerc who has taken victory in all the races Red Bull haven’t, and would have won more had car reliability issues not blighted his campaign. Nonetheless, the illustrious Italian team and their venerable scarlet cars are back in the game after years in F1’s wilderness. Ferrari are resurgent once more. But if it seems a long time between drinks, it wouldn’t be the first time that the sport’s most famous marque had lived through a drought.

In its early days, the world championship was dominated by an Italian team, but it wasn’t Ferrari. The very first F1 world championship Grand Prix was won by Giuseppe “Nino” Farina in an Alfa Romeo at Silverstone in 1950. The Alfas were utterly dominant throughout that first season and by the time F1 returned to the former airfield in Northamptonshire the following year, Farina was reigning world champion and Alfa Romeo had won every one of the intervening eight Grands Prix. Everybody knew who was the favourite to take victory at Silverstone again.

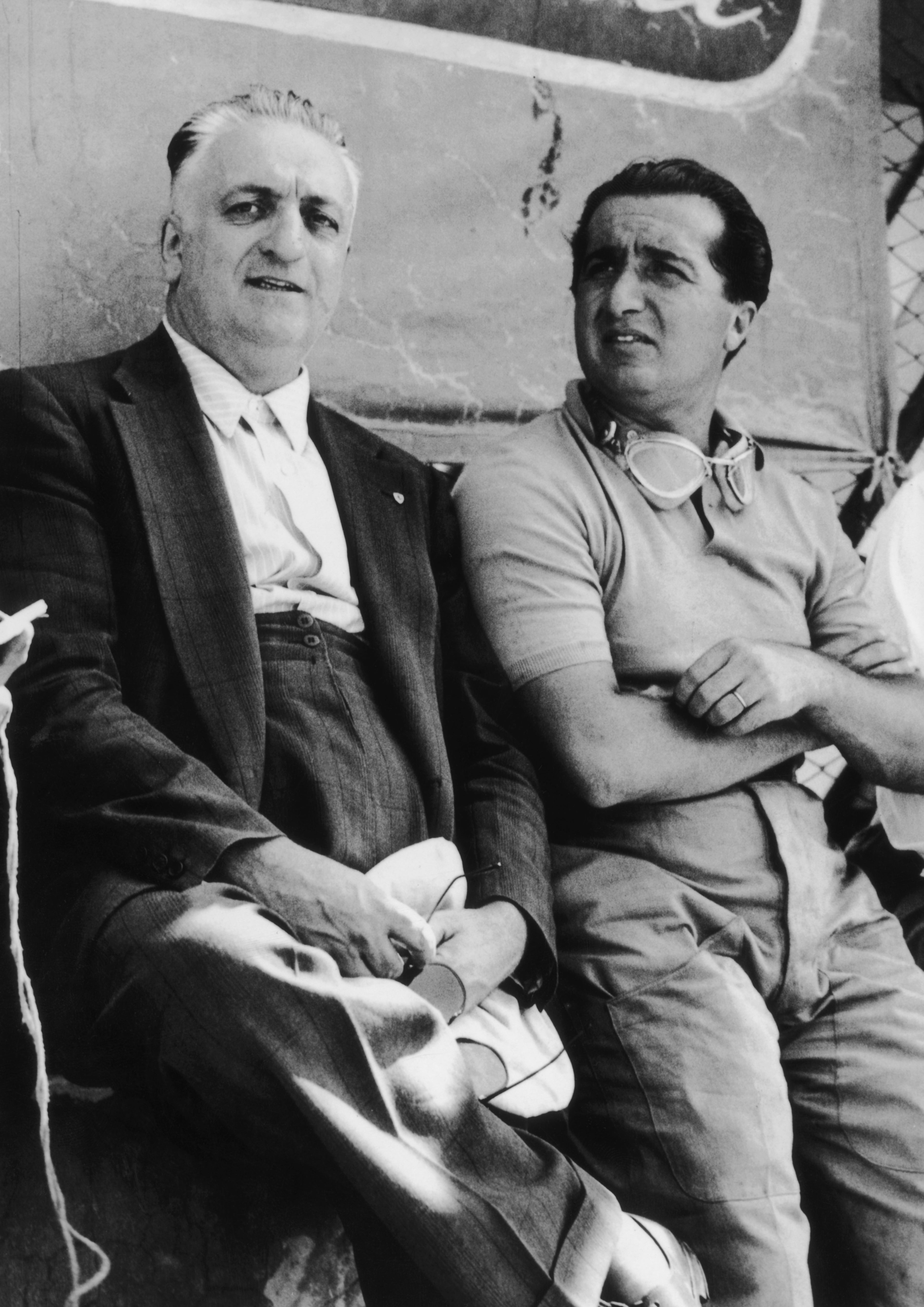

Everybody except a former farmhand from Argentina and his enigmatic Italian boss. They had spotted a flaw in Alfa Romeo’s strategy and arrived at Silverstone hoping to exploit it. The Argentine was Jose Froilan Gonzalez – Cabezon or “Big-Head” to his mates at home on account of his substantial girth, but known in Europe by the less brutal moniker of the Pampas Bull – and his boss was the man who over the subsequent decades would fashion the most famous of all F1 teams in his Delphic image: Enzo Ferrari.

Ferrari have competed in every season since the world championship began in 1950, the only team to do so. And while today the team are still considered the one every driver longs to race for – a career in F1 is thought by many to be incomplete without having done so – it was not ever thus. When that first world championship blasted off the grid the Alfas were top dogs, with the Ferraris trailing in their wake. And Enzo had good reason to be displeased. Prior to the Second World War, his eponymous team had been contracted to act as Alfa Romeo’s factory team, but in 1938 they had parted ways. Enzo did not like being crossed, and nor did he like his decisions being questioned. Even more, he didn’t like coming second.

Alfa’s drivers, throughout that great run of success in the early 1950s, were the three Fs: Italians Farina and Luigi Fagioli, and the Argentine who would later become five-time world champion, Juan-Manuel Fangio. Meanwhile, at Ferrari, the experienced Italians, Alberto Ascari and Luigi Villoresi, were backed up by compatriot Piero Taruffi.

Gonzalez – a long-time friend of Fangio – had travelled from South America to race for Argentina’s European racing team, hoping to take on the locals in the newly constituted world championship. But at the 1951 French Grand Prix, he had been asked by the Ferrari team to stand in for the sick Taruffi. He jumped at the chance and briefly led the race, but halfway through he was told to hand over his car to Ascari, the team leader whose own car had broken down. In the early days of the world championship, cars could be shared. Thinking he had somehow failed, Gonzalez was summoned to the Ferrari factory in Maranello and told to wait outside Enzo Ferrari’s office.

He later reported feeling sick and on the verge of tears. He expected a dressing down for some misdemeanour or for an error he must have made during the race. Instead, he left Maranello with a Ferrari contract in his pocket. Enzo had been impressed with his drive in France. “I had been summoned to meet ‘the sacred monster’ of motorsport and survived,” he said later. “I still felt sick. But this time with euphoria.” So tongue-tied had he been that Enzo assumed he had a speech impediment. “I couldn’t even think of the Italian word for thank you, only the Spanish,” he recalled. He would make his full Ferrari debut in the next race, the British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

As the new driver, he was given an older model Ferrari to that of his teammates. It mattered less, however, than the plan cooked up at the factory in Maranello. In the 1949 Belgian Grand Prix – the year before the world championship began – Ferrari had been beaten by Louis Rosier in a Talbot-Lago. Although the Talbot was slower than the Italian cars, its petrol consumption was much better. Enzo had taken note, as he did after every defeat, and was aware that the 1951 Alfa Romeos consumed fuel at an alarming rate – they were managing fewer than two miles per gallon. If his cars could conserve their fuel, their pit stop during the race would be shorter. Ferrari might have found the chink in Alfa Romeo’s armour.

Gonzalez’s photograph was not even in the programme for the Silverstone race and nor was he on the entry list, such had been the rapidity of his signing. He was happy enough to remain anonymous, describing himself as “a peasant made good”. In his debut race, he hoped to provide adequate back-up to his more celebrated and better-paid teammates. Except, even though he’d never driven at Silverstone before, he ripped the form book into pieces and qualified on pole position. Now the motorsport press was suddenly taking notice.

As start time approached Gonzalez began to get extremely nervous. “I kept pacing back and forth under tremendous tension,” he recalled. “I wandered aimlessly in a daze. It was a very foreign arena. My mind would not concentrate on anything but the race. I even carried on a conversation with myself: ‘What are you doing among so many field marshals? What will they say in Argentina? What will your parents think?’ The starting grid was Hades, breathing was difficult. I thought I would pass out. I even muttered out loud: ‘How will you get out of this?’” The five-minute horn interrupted his reverie and Gonzalez “had to rush to the toilet”.

He felt better as he climbed into his car. And as the flag dropped he and Fangio raced side by side under the spectator footbridge, before Gonzalez dived into the first corner ahead of Fangio and, to the surprise of the crowd, began to pull away from his Argentine mentor. Both had, in that first rush, been overtaken by Farina and Felice Bonetto in a one-off drive in a fourth Alfa. But by the end of the first lap the two Argentines were at the front and soon being instructed by their teams to drive their own races. Both were clearly faster than their teammates who had been left behind in the melee.

Eventually Fangio recovered from the shock of being usurped by his upstart compatriot and grabbed the lead on the 10th lap. “I knew he would have to make a pit stop just like me,” said Gonzalez, “so I didn’t fight and risk a crash. And we knew his stop would take longer than mine.” But Gonzalez kept close, sawing the wheel this way and that as his bulk was pushed first to one side of his cockpit and then the other, power-sliding his car through the corners in stark contrast to the relaxed, imperious style of Fangio.

Just before Fangio made his stop for fuel and tyres, Gonzalez retook the lead. Because of the huge tanks the Alfa required, filling them took an age and, with the car needing new tyres too, the pit stop took far longer than Ferrari’s would.

Minutes later Gonzalez received the instruction to bring his car into the pits. Ascari had retired his Ferrari. Disconsolate, Gonzalez brought his car in fully expecting to once again have to hand it over to his team leader. But Ascari was in generous mood. He had appreciated Gonzalez’s graciousness in handing over his car in France and had no intention of depriving him of the possibility of a maiden victory. He placed his hand on his Gonzalez’s shoulder and told the team to let him drive on.

Flirting with his car’s (and the track’s) limits, Gonzalez’s inelegant style kept him in contention, knowing that his shorter stop would likely decide the outcome. In the book Great Moments in Sport, motorsport historian Doug Nye wrote: “At the end of the straights he would choose his line, stamp on the brakes, fling on steering lock to make his car slide and balance it through the corner, wheels pointing straight ahead, now on opposite lock, whirling through the turn…” He was wringing the neck of his car. Twice he hit the protective straw bales lining the circuit. At one point he had to weave his way through them to get back on track. Racing journalist Maurice Hamilton’s book on the history of the British Grand Prix describes how Gonzalez seemed to “be trying to tear the steering wheel from its roots as he grasped the rim and appeared to physically push the car faster than it cared to go”.

It was enough. Not only was Fangio burning through fuel he was wearing through his tyres trying to keep pace with his countryman. He tried everything, his car juddering and vibrating through the turns, but the game was up – Ferrari’s master plan had come to fruition. “Towards the end I was more than a minute ahead,” remembered Gonzalez. “Not even Fangio could make up the time, so I eased off, even looking over my shoulder to check.” He recalled that the British crowd had “forgotten their usual restraint. They were jumping and waving and yelling like mad.”

Gonzalez had scythed his way to a famous victory. The Alfas were beaten, and by a team owned by the man they had fired. “Enzo killed his mother,” ran one lurid headline. Fangio, though, was magnanimous towards his compatriot and friend saying: “It’s your day. I always knew it would come.” “A phenomenon, this Froilan,” wrote a clearly impressed Autosport magazine.

Gonzalez was dragged from his cockpit in an almost bewildered state, thrust before his nation’s ambassador and then carried onto the podium to meet Queen Elizabeth, later to become Queen Mother. He couldn’t stop crying. “My wife Amelia was there,” he wrote in My Greatest Race. “She hugged me, the Argentine ambassador embraced me, all their faces blurred as they surrounded me, encircling me. I still feel their warmth and the moisture of their tears mingling with mine. They led me forward to meet the Queen of England. From all sides I heard cries I did not understand, hands trying to reach me, words not in my own tongue. It was strange music.” When the Argentine flag was hoisted and his national anthem played, the Pampas Bull cried again.

It was Ferrari’s first world championship race victory of 240 to date, more than any other team. Alfa Romeo would still go on to win the title that year – the first of Fangio’s five – but it would be their last. Ascari won the 1952 title and Ferrari have gone on to win 14 more drivers’ championships. As for the stocky farm worker turned international racing driver, the peasant who cavorted with the field marshals and the Queen of England, Gonzalez would win only once more. It was also at Silverstone, in the 1954 British Grand Prix, this time beating the dominant Mercedes team, coincidentally once more headed by Fangio.

Unfortunately, Gonzalez was injured shortly after his second British Grand Prix victory in an accident at the Dundrod Tourist Trophy race in Northern Ireland. He attempted a comeback but was never as competitive as before, although he did share victory in the 1954 Le Mans 24-Hour race with Maurice Trintignant. He died in 2013 aged 90, back home in Buenos Aires. Of his now-famous day in July 1951, he said: “Two weeks earlier I hadn’t been a Ferrari driver, now I was their first-ever winner, beating Fangio, beating Ascari, beating the field marshals.”

The tide of Grand Prix history turned that afternoon, just as it seems to be turning again today. Before Leclerc’s victory at this season’s Bahrain Grand Prix, it had been three years and 45 races since Ferrari had last won, a drought even longer than that of the early 1950s. Gonzalez would doubtless appreciate the emotional high that success after so long can bestow on both driver and team. He took the memory of his 1951 win to the grave still telling people who would listen that “I often find myself again in that turmoil of hands, voices and cries which, if I close my eyes, I can still see and hear around me…”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments