‘We won’t let Jaywick die’: How the residents of England’s poorest town are taking a stand against coronavirus

In a pandemic that disproportionately affects the poor, the odds would appear to have been stacked against Jaywick Sands. But that’s not the whole story, writes Laurie Churchman

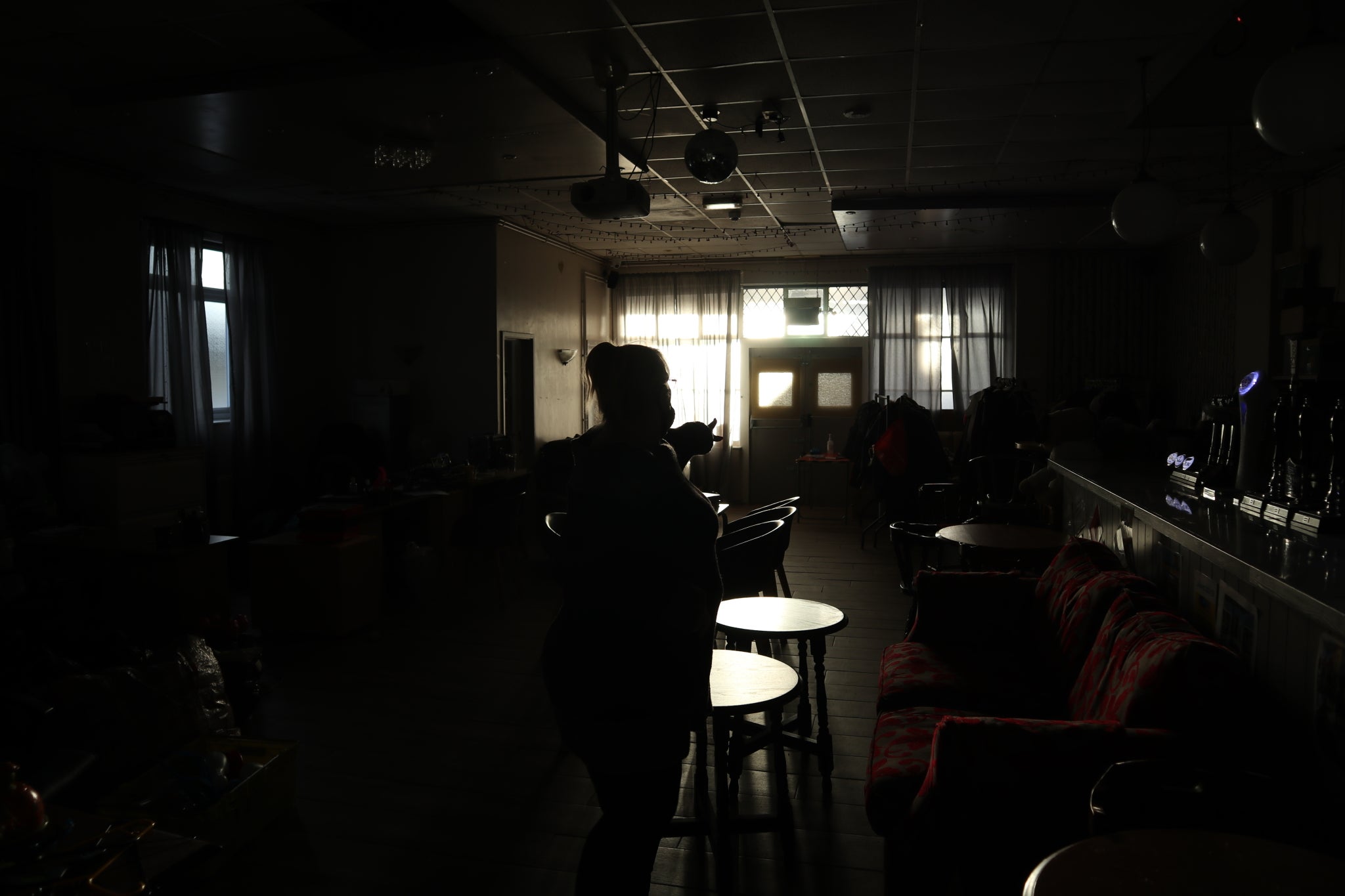

Landlady Jayne Nash flicks a switch in the back room of the Never Say Die pub. The light falls on a storage unit stocked as if for a military operation. There are stacks of tinned food, bags of pasta and tubes of toothpaste. By an old set of beer taps, there are rails of donated uniforms. But they’re not for an army – they’re for schoolchildren.

Jayne sighs. The makeshift food bank was refilled this morning. It’s already half empty. “People really rely on us,” she says. “The lockdown’s been horrendous for Jaywick, but we’ve got to keep going. Who else is going to help?”

The food bank has been a lifeline for more than 3,000 people – around half Jaywick’s population. In a pandemic that disproportionately affects the poor, the odds would appear to have been stacked against Jaywick Sands. But that’s not the whole story.

The Essex resort has topped a government index of the most deprived parts of the country since 2010. It has high rates of unemployment, and many of its residents have chronic health problems and depend on benefits. The housing in some parts of the seafront estate is falling apart.

According to the Office for National Statistics, people in the most deprived areas of England and Wales are more than twice as likely to die after contracting Covid-19.

Initially, Jaywick escaped the high infection rates seen elsewhere in Essex. Before Christmas it was among the last places still under the lower Tier 2 coronavirus restrictions. But as the new Covid-19 variant spreads, cases are on the rise. Many people here now know someone in the resort who has died.

Jaywick is facing huge challenges, but defiance has always been the watchword of this often-maligned community.

Simon Scott, out for his daily walk along the seafront, has been undergoing chemotherapy in the middle of a pandemic. But he says he doesn’t feel overwhelmed. The 62-year-old was diagnosed with cancer during the first lockdown and has been shielding alone at his home in Jaywick ever since. He believes people here are resilient: “We just get on with it – we’re used to putting up with a lot.”

The area has endured decades of neglect, and its history is often portrayed as an example of a failed social experiment. Jaywick Sands was dreamt up in 1928 as a budget bolthole for East Enders looking to get out of the capital.

The resort was the brainchild of property developer Frank Stedman, who encouraged Londoners to buy cheap plots of land and build their own homes on a patch of former salt marsh by the sea.

The new village drew workers from the Ford plant in Dagenham. Houses were made from the firm’s wooden packing crates, and streets were named after makes of cars – some of them now just a dim motoring memory. There are Austin, Alvis and Humber Avenues, and a Lotus Way. The roads were even set out in the shape of a car radiator grille.

There were coaches from London to the coast, amusements, even a toy train. Jaywick was sold as a place to exercise and take in the sea air, a new life for as little as £25.

It wasn’t long before the cracks started to appear.

Bombed-out East Enders began to flee London, their homes reduced to rubble during the Second World War. Flimsy holiday housing was soon home to families living full-time in Jaywick. The temporary properties buckled under the pressure. Today, many residents are still living in cramped, poorly built short-term accommodation.

One of the biggest problems, according to local historian Norman Jacobs, was that Clacton council didn’t approve of the whole idea of Jaywick. “It warned the area was prone to flooding, and when the development went ahead anyway, they wouldn’t provide support – no electricity, no water, no doctor’s surgeries,” he explains.

In January 1953, Jaywick did indeed become one of the places worst-hit by the North Sea floods that swept across England’s east coast. Thirty-five people – one in 20 of the population – died when a violent storm coincided with a spring tide. The surge circumvented the resort’s sea defences. Some residents drowned in their beds.

The problem of neglect hasn’t gone away. Scott says when he first moved to Jaywick from West Ham five years ago, his pothole-ridden street looked “like something from the 17th century”.

Over time, Jaywick has come to be seen as something of an embarrassment for the authorities – not least when the resort received a high-profile visit from a UN special rapporteur on poverty and human rights in 2018 as part of an investigation into Britain’s treatment of the poor. After hearing moving testimonies from people in Jaywick, Philip Alston launched a stinging attack on what he saw as Britain’s lack of support for the most vulnerable in society.

Promises of development and big investment come and go so often they’ve become something of a joke here. But recently Jaywick has been seeing the benefits of an injection of cash. The roads of the estate are covered in fresh tarmac now. And despite the grim statistics and talk of decay, many residents say they wouldn’t want to live anywhere else. The sense of belonging is palpable. Jacobs says the feeling of being overlooked for so long has helped forge a strong, tight-knit community.

Residents have resisted moves to demolish parts of the estate. And they have grown tired of hearing their town described as deprived. They have a different story to tell.

Scott says the resort’s sense of community is evident in the good-natured way people say thank you as they get off the bus, and, during the Covid crisis, how they’ve worn their masks and followed social distancing rules to protect one another. Tales of drunken fights and degradation on the internet don’t reflect what Jaywick is really about.

Countering the bad reputation and misrepresentation is part of what it means to live here. There was outrage in 2018 when a photo of a Jaywick street was used in a misleading Republican campaign advert about the dangers of urban decay in the US.

There was anger, too, over the estate’s portrayal in the Channel 5 documentary series Benefits by the Sea. Residents branded it “poverty porn”, claiming the producers had deliberately filmed in the most dilapidated properties.

One band of locals got so fed up with the negative publicity they founded the Jaywick Sands Revival Group to “dispel the myths” about the seaside resort. The group is now drawing on the same spirit of defiance as it confronts a huge new challenge in the pandemic.

Using local grants, the campaigners took over the Never Say Die pub in August, transforming it into a hub for Jaywick’s grassroots response to Covid. “It’s been brilliant,” says co-founder Rosina Herriott, 72. “We’re get-up-and-goers – we had an idea and just ran with it.”

When the government initially refused to provide free school meals over the October half-term holiday, the pub stepped up and dispensed hundreds of packed lunches.

Volunteers have been delivering groceries to elderly and vulnerable people in isolation, handing out school uniforms and offering careers advice in an area devastated by the economic impact of the virus. As pubs around the country shut down for good, the takeover has been an astonishing success. The Never Say Die has weathered two lockdowns, and staff are making sure the volunteer operation carries on through the third.

“People get the wrong idea about Jaywick,” says Jayne Nash. “We might be deprived in terms of money, but you can’t say that about community spirit.” She believes this means people in Jaywick are better equipped than it might seem to cope with Covid-19.

“People care about each other round here,” she says. “Everyone’s got a mask on in the shops. Because it’s such a small community, we know if we do this we’re going to keep the numbers down in the pandemic.”

The Never Say Die’s food bank is still open, but the main bar is shut under the latest lockdown. The view from the window is a bleak reminder of the economic reality. Shop fronts have their metal shutters pulled down tight. “The lockdown’s had a massive impact,” Jayne says. “We’ve got a lot of disabled and elderly stuck on their own in their bungalows, and it’s been killing us financially.”

At the local shop, The Stores, owner Ali Kaya has watched Jaywick’s high street become a “ghost town” as businesses close their doors all around him. The seafront arcade is long since closed. The pubs, the hairdresser and the tattoo parlour are all shut. Some businesses fear they may have to pack up for good.

“Shops here have taken a big hit,” Ali says. “There’s barely anyone about on the streets. If this carries on long-term, not many businesses will survive. Government grants just won’t cover it. We still keep hearing about people dying. I just don’t know what’s going to happen. I’m holding out hope things are going to get better. What else can I do?”

Ward councillor Dan Casey understands it has been difficult for Jaywick’s businesses. He knows people are struggling financially in every corner of his patch, but his chief concern is the spread of the virus. He speaks of his fears for a 96-year-old woman who contracted Covid-19. Terrified by stories of coronavirus tearing through the care sector, she dreaded having to go into a local nursing home.

“She told me before she went in she was worried about getting the virus. Now, she’s come down with it, and I heard she’s not eating anything.”

“Three people died on the estate the other week,” he said. “It hits you when it’s people you know.” He is optimistic the resort can bounce back after the pandemic, but admits it could take time for Jaywick to get back on its feet.

At the Never Say Die, the volunteers are focusing on the people they can help directly. A man walks in off the windswept beach asking for a hand with a job application, and Jayne offers to fill in his reference forms.

She remembers a mother-of-four who came in recently, pregnant and unable to afford anything for Christmas. “We gave her a tree and did gifts for her mum, dad and nan,” she explains. “Someone even donated a pram. We gave them a dinner ready to cook on Christmas Day, and she was just in tears.

“No one here should have to go without now,” Jayne says. “We’re going to make sure of it – we’re not going to let Jaywick die.”

You can donate to the Jaywick Sands Revival group here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks