For people with endometriosis, getting a diagnosis, treatment and a cure is still a waiting game

Despite millions suffering its debilitating effects, the conition remains taboo. It’s time to bring research and awareness to the forefront and find a cure, says Enis Yucekoralp

Endometriosis is a debilitating and chronic medical condition that affects around 1 in 10 women. In the United Kingdom, that equates to over 1.5 million sufferers: the second-most common gynaecological condition in the country.

Agonising and under-diagnosed, endometriosis is not just incurable at present but incurably underfunded: the average diagnosis time currently stands at an astonishing seven and a half years. Considering its life-destroying and debilitating effects, that endometriosis remains as unresolved and enigmatic in 2020 is unacceptable.

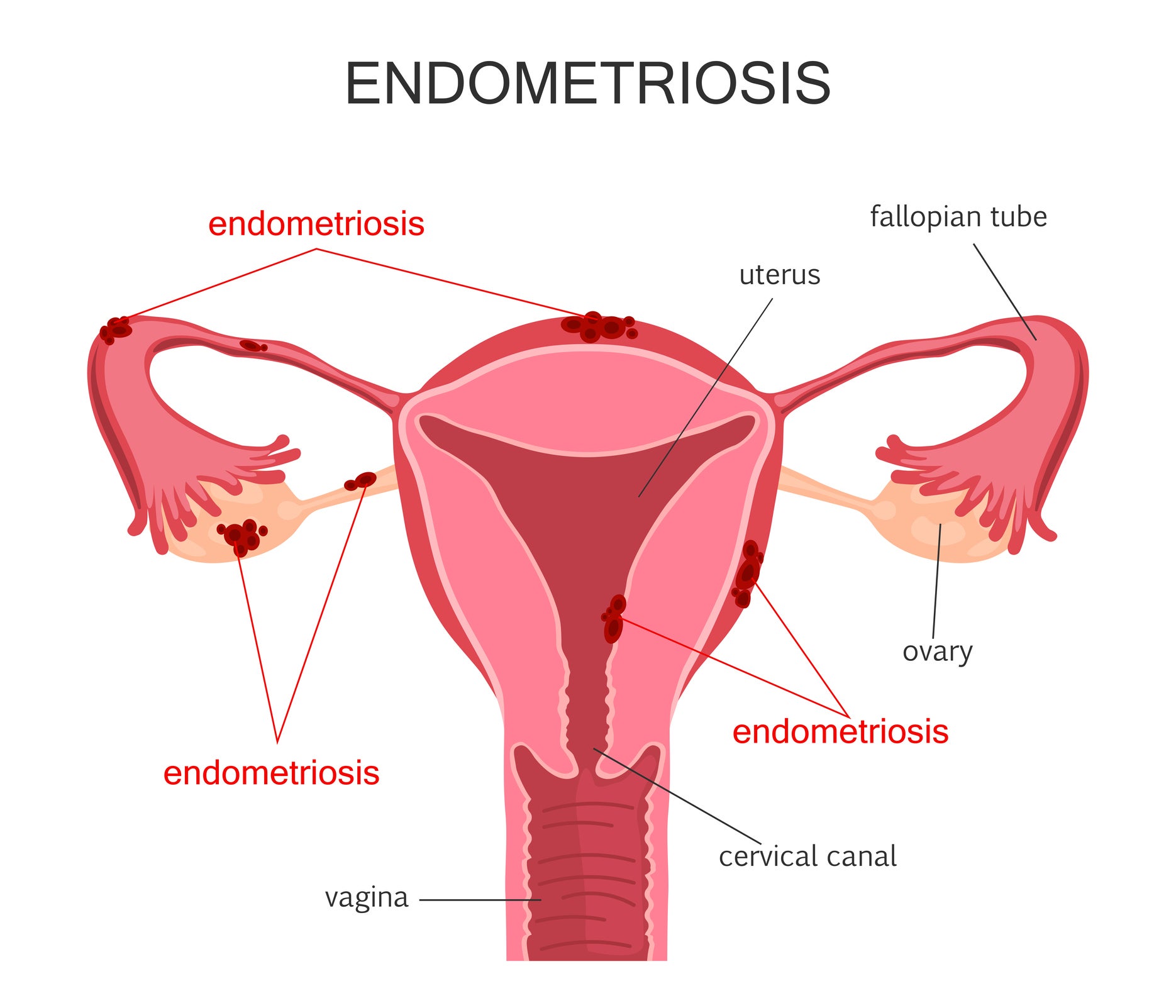

femIts cause is still unknown and until more research is conducted a cure seems consigned to the waiting list. At root, it occurs when cells similar to those found in the tissue lining of the uterus (the endometrium), grow elsewhere in the body – most commonly around the fallopian tubes, the ovaries and surrounding area, and other tissue around the uterus.

Every month, these cells follow the menstrual cycle of the uterine tissue. However, unlike the cells in the womb that leave the body during menstruation, the blood becomes trapped and causes acute pelvic pain, heavy and painful periods, and often leaves renders patients infertile.

According to the NHS, the common symptoms of endometriosis (which can vary in presence and intensity) are multivalent and difficult to systemise because, among other things, bowel problems and the menstrual cycle are linked.

Symptoms include: pain in the lower stomach or back (pelvic pain), which is usually worse during your period; period pain that prevents your usual activities; pain during or after sex; pain when urinating or defecating during your period or at other times; nausea, constipation, diarrhoea, or blood in your urine during your period; or difficulty getting pregnant.

Heavy periods are also symptomatic of endometriosis – the notion of what is deemed a “normal” period for someone, as against a painful, heavy period also leads to diagnostic confusion.

There is anger, and resentment, but it’s a question of who do you direct that to? It’s not the doctors’ fault – it’s a long, long line of lack of funding and everything else

Despite the severity and widespread nature of endometriosis, the latency of diagnoses has been partially attributed to the fact that its symptoms have much in common with other conditions.

Globally, 176 million, or 10 per cent, of people assigned female at birth (AFAB) are affected. Although the condition is intensely endemic, it seems to languish in relative obscurity: 64 per cent of young women have never heard of it and three-quarters of men have no idea what it is. This lack of recognition is one of the major issues to contend with.

That said, the past few years have at least seen a small rise in public conversations around endometriosis; this year The Independent has produced a series of stories and news pieces. Celebrity disclosures, such as Alexa Chung’s attention-raising Instagram post earlier this year, also greatly facilitate discussion. As it is with many issues that lack comprehensive awareness, conversations and topical traction are key to getting the word out.

In October 2019, British MPs announced plans to launch an official inquiry into endometriosis after the results of a BBC study that allowed 13,500 women to broadcast its detrimental impact on their lives. Nearly all of the participants said their condition significantly damaged their mental health, sex lives and careers.

64%

of young women have never heard of endometriosis

Approximately half of those surveyed expressed that they had experienced suicidal thoughts, while the majority of respondents told researchers they relied on monthly prescription painkillers.

Once the research was published last year, an inquiry was planned by MPs that would offer patients and healthcare practitioners the opportunity to advise the government on the best ways to intervene through first-hand experience.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Endometriosis was set up in 2018 with the express purpose of raising awareness of the condition across all political parties in parliament.

In February 2020, the APPG officially launched its inquiry into the diagnosis, treatment and support options available for endometriosis. Endometriosis UK, the country’s leading charity on the condition, is also providing support.

They said that information has already been collected from 13,000 of those with the condition and that MPs are continuing to gather data and evidence from healthcare professionals.

Organising this evidence into a report to be published in October 2020 will provide the government with a set of recommendations on how to improve the provision of care for the millions of people in the UK with endometriosis.

Emma Cox, CEO of Endometriosis UK, tells me: “We'd like the governments in all four nations to recognise endometriosis and the impact it can have, and, to ensure that the health departments and the NHS in each nation plan accordingly.

“I know the NHS is under pressure, but people shouldn’t have to go to a GP multiple times, shouldn’t be sent to the wrong specialist, shouldn’t be going to A&E to get help if there’s a clearer pathway.

“What I’d like to see is endometriosis diagnosed, treated and have more effective pathways so if you’ve got suspected endometriosis you should be seen by a specialist who has training in looking after and recognising the condition, not being seen by a general gynaecologist.”

The impact of Covid-19 and the need to gain extra insight into its impact on endometriosis sufferers has delayed the initial publication of the APPG’s research.

“Due to the pandemic, the NHS has the unenviable job of managing huge waiting lists from cancelled surgery and appointments. We need to ensure that endometriosis doesn’t get forgotten about and that the impact it can have is not minimised,” Cox says. “We all know there’s going to be delays as services resume, but there are a lot of people who have had surgery or treatments put off.”

Encouragingly, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has issued a proposed guidance framework for gynaecological services during the pandemic, which includes endometriosis.

“Historically, endometriosis has been often overlooked. Let’s not do that this time. Let’s give it the due priority it needs along with everything else,” she adds. “I think we should learn from some of the things that have happened with Covid in terms of access via remote consultations, for example.

“While that won’t work for everyone, and people should be able to see a specialist face-to-face if they need to, we don’t want to just leave people who were due to have quite life-changing surgery in March and April to not hear anything for months.”

50%

of women with endometriosis become infertile

As well as the issue of pathways for treatment, another area this report hopes to improve is the recognition of endometriosis on a wider scale. With both mental and menstrual wellbeing added to the 2020 primary and secondary school curriculum in England – though not yet the rest of the UK – a fundamental opportunity has emerged this September.

Young people will be taught how to recognise symptoms, to know the right biological terminologies and to overcome any fears or embarrassment about menstruation.

Education is vital in addressing the lack of understanding around endometriosis. It enables and empowers people, particularly young sufferers, to talk about it in practical terms and seek help.

Cox tells me: “I think one of the real challenges we have with endometriosis is that the extent it grows and the impact it has varies from person to person and it can be a real spectrum.

"Some people will be debilitated by the disease – they might not be able to work, it could impact all aspects of their life – whereas others might actually have endometriosis but limited symptoms: others might not even know they’ve had it.

It is extreme to have a six-inch needle plunged into your stomach each month. It is extreme to go through the menopause at 25. It is mind-boggling that the only options available to me for endometriosis were radical hormone treatments and invasive surgery

“Some people might find out and decide they want surgery and that’s completely fine, but I think one of the challenges, for me, is how do we raise awareness without scaring everybody that isn’t going to get it really seriously?

“It’s estimated that 20 per cent of those with endometriosis have it on their bowel, bladder, or impacting on other organs significantly and we need make sure they get help and that people recognise the impact it can have on their life, but how do we do that without scaring, for instance, the 18-year-old who has just been told they’ve got endometriosis? That’s one of our real challenges.”

By raising medical awareness of the condition, symptoms can be recognised and GPs empowered to suspect the presence of endometriosis.

In fact, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines require that healthcare professionals consider endometriosis as a possible diagnosis if any one of the listed symptoms are present. If someone is suffering from chronic pelvic pain the issue should be resolved not just superficially but as a means of diagnosing the root cause.

“Specialist centres can only see 20 per cent of the patients,” Cox explains, “so there's 80 per cent of patients who are likely being seen by a general gynaecologist, without specialist training in this area, and I think that's wrong.”

Indeed, as she states, the NICE guidelines stipulate that there should be an endometriosis specialist in every gynaecology centre – this includes a recommendation that certain types of endometriosis, for instance, those affecting the bowel, are always treated by a specialist.

By its nature, an average approximates. It disguises those being diagnosed in under a year but it does the same to those being diagnosed in 15 years: double the national average.

As of yet, there is no blood test for endometriosis and though cysts may sometimes show up on scans there is no simple way to test for it. The only way to achieve a long-fought diagnosis is through a surgical operation called a laparoscopy.

Zoe King, a creative educator who has suffered with chronic pain and gynaecological symptoms for 14 years, eventually underwent a laparoscopy to definitively diagnose her endometriosis this year. “I finally had the surgery, and, along with endometriosis, they found three cysts”, she tells me, “one on each ovary and one in the fallopian tube.”

“They made three incisions – one with a camera – then they fill you up with gas and have a look around. If there is stuff to take away they can remove it, but having this operation is the only way of getting diagnosed. Then the recovery in total is probably around 12 weeks, so it’s not a quick little procedure,” she adds.

“It’s strange – you finally get diagnosed, but there’s not proven treatment to help and there’s no cure. You’re just left sort of having to try things that might help, not things that definitely will help. You just have to get through it relying on brave women to put themselves forward for testing, to then help others with similar conditions.

“Some women only get diagnosed with endometriosis after trying to conceive naturally and there being a problem, then investigations and a laparoscopy reveal there’s endometriosis.

“Not every woman will have symptoms, but, although it’s awful to be in so much pain, in a way at least you sort of know that something's not right to push to be tested,” she says. “For some women it's heartbreaking for it to have been left so long that you then can no longer have children.”

Up to 50 per cent of those afflicted are infertile and up to 10 per cent of the general female population is afflicted with endometriosis, according to a 2010 study published in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics.

There is five times the amount of research into erectile dysfunction (which affects 19 per cent of men) than there is into understanding PMS (which affects around 90 per cent of women)

For some cis women or trans, intersex, and non-binary patients, endometriosis can have a colossal impact on their life – bringing it to a standstill or else miring them in depression or other mental health conditions.

Testimonies, such as Cori Smith’s account of being a trans man with endometriosis, detail the condition’s complex discriminations and misinformed biases.

On his transition and the multiple challenges of endometriosis, Smith wrote: “I think most can agree doctors can be insulting, misinformed, and uneducated — when speaking to you about your body, and endometriosis.

“Combine those with the fact that someone could be transgender, non-binary, or intersex, and you have served a mystery to your doctor. A scenario which is common, but not common enough for doctors to understand how to appropriately talk to someone going through it. Unfortunately, this can lead to even more mistreatment.”

While it is not a universal experience, many patients have been dismayed by doctors’ blasé dismissal, downplaying or incredulity of their painful symptoms of endometriosis.

A medical cynicism that labels manifest pain as imagined “women's issues” makes a lack of treatment and delayed diagnosis the inevitable consequences. Sometimes patients’ complaints and details are recorded inaccurately, or they are patronisingly told they have a low pain threshold, or, despicably, that they are simply “hysterical”.

This is something Zoe King has also experienced as a patient throughout the years: “The first time I felt symptoms were probably when I was around 16 years old when I started getting recurrent, unexplained UTIs. I wasn’t sexually active, but as a young woman I felt doctors wouldn’t believe me or they would accuse me of being unhygienic – just really, really patronising. This was from various GPs, both male and female.

“Then, that sort of just continued over the years. They didn’t put me forward to have any tests done, they would just constantly prescribe long-term antibiotics which it later transpired caused scarring of the lungs in some patients. After that, it was then people telling me I had IBS, because I would just get a really swollen stomach and just be in a lot of pain.”

“I love the NHS so much. My mum has worked for the NHS for 40-odd years, but there’s just lack of funding everywhere.

“There is anger, and resentment, but it's a question of who do you direct that to? It’s not the doctors’ fault – it’s a long, long line of lack of funding and everything else. Which is why it's important to have conversations, to give women the confidence to go to the doctor's and declare their symptoms.”

It wasn’t until she went to see a new GP, told him that her ovulation pain had become worse than her period pain, and eventually had a physical exam that demonstrated the excruciating pain in her ovaries that they finally agreed with her suspicion that it was endometriosis and pursued testing.

The frustration of the issue is that it is clear that some GPs are extremely adept at identifying the symptoms of endometriosis while some are not. In terms of effective wholesale diagnoses the goal is to make the particular, universal.

An issue of language: tampons and pads are always referred to as ‘sanitary products’ or as discreet ‘feminine hygiene’ products, but this contributes to the misinformed fallacy that periods are somehow 'dirty’

Contemporary medicine – rooted as it is in the patriarchal system – seems to continue to misogynistically dismiss or neglect the concerns and complaints of others.

The outrage that followed a study by Italian doctors, one which sought to rate the attractiveness of women with different stages of endometriosis, was entirely justified and speaks to the persistence of chauvinist attitudes in medical discourse.

There remains a gender bias in medical science and research funding. There is five times the amount of research into erectile dysfunction (which affects 19 per cent of men) than there is into understanding PMS (which affects around 90 per cent of women). A damning indictment of a historical disparity.

Due to funding decisions being made by men, there has undoubtedly been less research into women’s health than in other medical conditions.

What we desperately need is an increased drive for research into endometriosis– we need to find out what causes it and how to cure it, while more investment and knowledge will allow medical professionals to design better treatments and to drastically reduce the latency of diagnoses.

Perhaps due to menstruation stigma, this can also be an issue of language: tampons and pads are always referred to as “sanitary products” or as discreet “feminine hygiene” products, but this contributes to the misinformed fallacy that periods are somehow “dirty”.

Indeed, endometriosis is linked to a range of taboo subjects, which further precludes discussion of the condition. Whether periods and menstruation, bowel issues and faeces, or women’s fertility, the fact that it is also essentially an “invisible” condition contributes to the lack of understanding and recognition of its hidden effects. As well as being faced with dubiety in the doctor’s surgery, many patients are accused of truancy and absenteeism for simply being subject to a relentless cycle of hidden menstrual pain.

The pressures from employers and schools can contribute to complicating the associated impacts of endometriosis. This brings with it an added unnecessary stress, coupled with the anxiety of whether a flare-up is going to come at an inopportune time at work or in their personal lives.

Cox explains that “from an employment perspective, there can be a lack of understanding for those people that have cyclical menstrual conditions who suffer from symptoms intermittently, not all the time. Their manager's attitude may be it’s just something that ‘all women have to deal with’ or they are labelled ‘flaky’. It can be the same with menopause and other menstrual conditions.

There is evidence to suggest that the wide-ranging burdens of endometriosis – in terms of treatment, healthcare, and lost work – costs the UK economy £8.2 billion annually

“There’s also something specific for young people with the condition, because of the length of time to diagnosis. Those suffering as adolescents may miss school, college and exams, and not get the support or consideration they need as they don’t have a diagnosis. Not attaining their potential in education will affect their work options, career and have an impact for life.”

The world of work can sometimes operate as an exclusionary system, one which mirrors society in its pervasive intolerance of real difference. In terms of chronic or intermittent conditions such as endometriosis, the overvaluing of presenteeism in patriarchal capitalism does not allow for the recognition or leniency of monthly staff absences.

Certainly, there are also a range of associated costs incurred by endometriosis that extend beyond medical health. By being forced to suspend working careers, to settle for part-time work, drop hours, or take time off, those suffering with the condition will be denied tens of thousands of pounds worth of lost income and salaries. This could also impact on future earnings and pension savings.

All this, together with spending on treatment plans and possible private surgeries, results in a collateral impact of financial woe for endometriosis sufferers. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that the wide-ranging burdens of endometriosis – in terms of treatment, healthcare and lost work – costs the UK economy £8.2bn annually.

On an individual level, raising the issue with people who may be affected is vital – its ubiquity means that everyone will know someone who is dealing with endometriosis. At the very least, being prepared to talk to people sensitively about menstrual issues is something everybody can muster.

Endometriosis UK continues to campaign valiantly and successfully to raise awareness for the condition. Events like this summer’s Walk for Endo – a fundraising initiative that challenges supporters to walk 7.5km in solidarity with the long average wait times facing endometriosis sufferers – generate essential funds to continue the amazing work that the charity does.

Working with the APPG to apply pressure to the government, collaborating with the Royal College of General Practitioners and other institutions, and those in the press and media to raise awareness, Endometriosis UK provides the inspirational blueprint.

“What we really want to see is diagnosis times coming down,” Cox says. “It’s not a disease where someone’s going to walk in and have one appointment and be diagnosed; however, I do believe that in five years times average diagnosis time should be three or four years; in 10 years’ time it should be under a year on average. We need a real push to do that.”

At its root, the aim is to see comprehensive recognition for endometriosis, to raise awareness through education, to greatly amplify the number of scientific studies into the condition, and to enable its sufferers to access help, support and effective treatments as soon as possible. We need to fight on all fronts to find a cure.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks