Utopia and Decline: East German art finally comes in from the cold

Unlike their western counterparts, artists in East Germany could make a good living painting – as long as they painted what the state wanted. William Cook is in Dusseldorf for an exhibition of these rare and long-forgotten works

In the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, a grand Art Deco gallery beside the River Rhine, German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier is opening an exhibition of East German Art. The huge hall is crowded with sleek Teutonic VIPs. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this is the first major survey of East German Art mounted since German reunification. But why is it happening here, in one of Germany’s most westerly cities, so far from Eastern Germany? And why have we had to wait so long to see this forgotten, forbidden art?

Growing up half German in Cold War Britain, the child of two artists, from my earliest years I was immersed in German art. My uncle was an artist too, a student at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie (one of Germany’s leading art schools) under the great German artist and iconoclast Joseph Beuys. From what my parents told me, I soon became aware that there was a revolution sweeping through German art. Young West German artists (particularly at Düsseldorf’s Kunstakademie) were confronting the horrors of the Third Reich and the guilty amnesia of the postwar years, in which Germans worked hard, lived the good life and tried to forget about their awful past.

The result of this uneasy toil was the Wirtschaftswunder (Economic Miracle) which transformed West Germany from a pile of rubble into Europe’s most prosperous nation. Yet something important got lost along the way. West Germans had embraced materialism, aping the brash consumerism of the United States, in an attempt to forget about what happened between 1933 and 1945. A new generation of West German artists were now addressing this omission, especially in Düsseldorf. Many of these artists (Georg Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke…) had fled here from the East.

Whatever you said or did could (and probably would) be reported back to the authorities. Consequently, for safety’s sake, most people kept their heads down. But how can you keep quiet and still make decent art?

My uncle was a bit-part player in this revolution. He settled in Cologne, not far from Düsseldorf, and branched out into music, working with Karl-Heinz Stockhausen. He even appeared on British television once or twice. My father had been born in Eastern Germany (in Dresden – he survived the bombing as a toddler). My German grandparents were both born in the east, and fled west in 1945, taking the same route as many of those East German artists.

But what about the artists who remained in East Germany? About them we knew next to nothing. It’s these neglected artists which this new exhibition (Utopie und Untergang – Utopia and Decline) seeks to rehabilitate. “We wanted to show the richness of the art which was produced there, and to show how different it is,’’ says the museum’s director, Felix Krämer. “There’s abstraction, there’s humour.’’ It’s not all pictures of happy workers.

During the Cold War, it was hard for anyone in West Germany (or western Europe) to find out what was really happening in East Germany – and that also applied to East German art. All of the news networks were under communist control, personal communication with the west was monitored and the Ministry for State Security (aka the Stasi) scrutinised every area of public and private life, supported by a huge network of informers. Whatever you said or did could (and probably would) be reported back to the authorities. Consequently, for safety’s sake, most people kept their heads down. But how can you keep quiet and still make decent art?

Like the Nazis before them, the East German government took fine art very seriously. They recognised its power to shape popular opinion, to change the way people think. Like the Nazis, they were determined to eliminate any art they didn’t like, but their methods were more subtle. Any artist who wished to exhibit or sell their work had to apply for membership of the Association of Visual Artists, an organisation closely controlled by the East German state. If you were a member, your output was regulated and censored by the party. If you weren’t a member, your work effectively disappeared. Hence, it’s hardly surprising that East German art was so little known in the west. The official stuff was anodyne, and the unofficial stuff was hard to find.

Any artist who wished to exhibit or sell their work had to apply for membership of the Association of Visual Artists, an organisation closely controlled by the East German state

What’s more surprising is that, in the 30 years since the Wall came down, hardly any East German art has been exhibited, and never on this sort of scale. Why not? Well, when the East German state disintegrated, two things happened which kept East German art hidden for a generation. The state-sanctioned art was removed, and the communist curators were replaced by new curators from the west, who knew nothing about East German art.

When I first went east, in the early Nineties, I found no art from the GDR years on gallery walls. Everything produced between 1949 and 1989 had been taken down and hidden away. In Chemnitz (formerly Karl-Marx-Stadt) I asked the curator why there was nothing in the gallery from the last 40 years. He told me it was locked away in the basement. When I pressed him, he produced a key and took me down there for a tour. The art I found there amazed me, and this new exhibition reminded me very much of what I saw.

So what made East German art so special? Isolation. During the Cold War, West German art was heavily influenced by America, particularly by Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Conceptual Art. East German artists had scant access to these movements. The government disapproved of them – they regarded Abstract Expressionism as western propaganda.

In some respects East German artists missed out as a result of this exclusion, but it made their work more individual, more distinctive. For this show, the Kunstpalast has gathered together the work of thirteen artists who lived and worked in the GDR. The breadth of their work is extraordinary, ranging from expressionism to surrealism, from figuration to abstraction.

Naturally, East Germany had its own artistic orthodoxies, most notably the cult of Social Realism, which the Soviet Union decreed was the only suitable artistic style. As in virtually every other matter, East Germany followed the Soviet lead. Social Realism was de rigueur and every other style was verboten. “The GDR thought art has a meaning and a purpose,’’ explains the exhibition’s curator, Steffen Krautzig, over drinks on the opening night, in a quiet corner of this crowded gallery.

"Ordinary people have to be convinced by the art – the art has to be readable very easily. Surrealistic art is more than this. It’s poetic, it’s mysterious – you cannot read it easily.'’ Hence Surrealism was beyond the pale, like most other genres you can think of.

Culture and art played a big role in the East. You had to tow the line, and if you did you were guaranteed a level of security rarely available to artists in the west. You could live from it, as long as you made what they said. If not, there could be a problem

Krautzig was born and raised in East Germany. He was 12 when the Wall came down. “Culture and art played a big role in the East,’’ he recalls. You had to tow the line, but if you did you were guaranteed a level of security rarely available to artists in the west – a regular job and a steady income. “You could live from it, as long as you made what they said,’ says Steffen. ‘If not, there could be a problem.’’ In West Germany artists had the opposite problem. They were free to paint what they wanted, but they were at the mercy of the market. They had to hustle and hawk their artworks to survive.

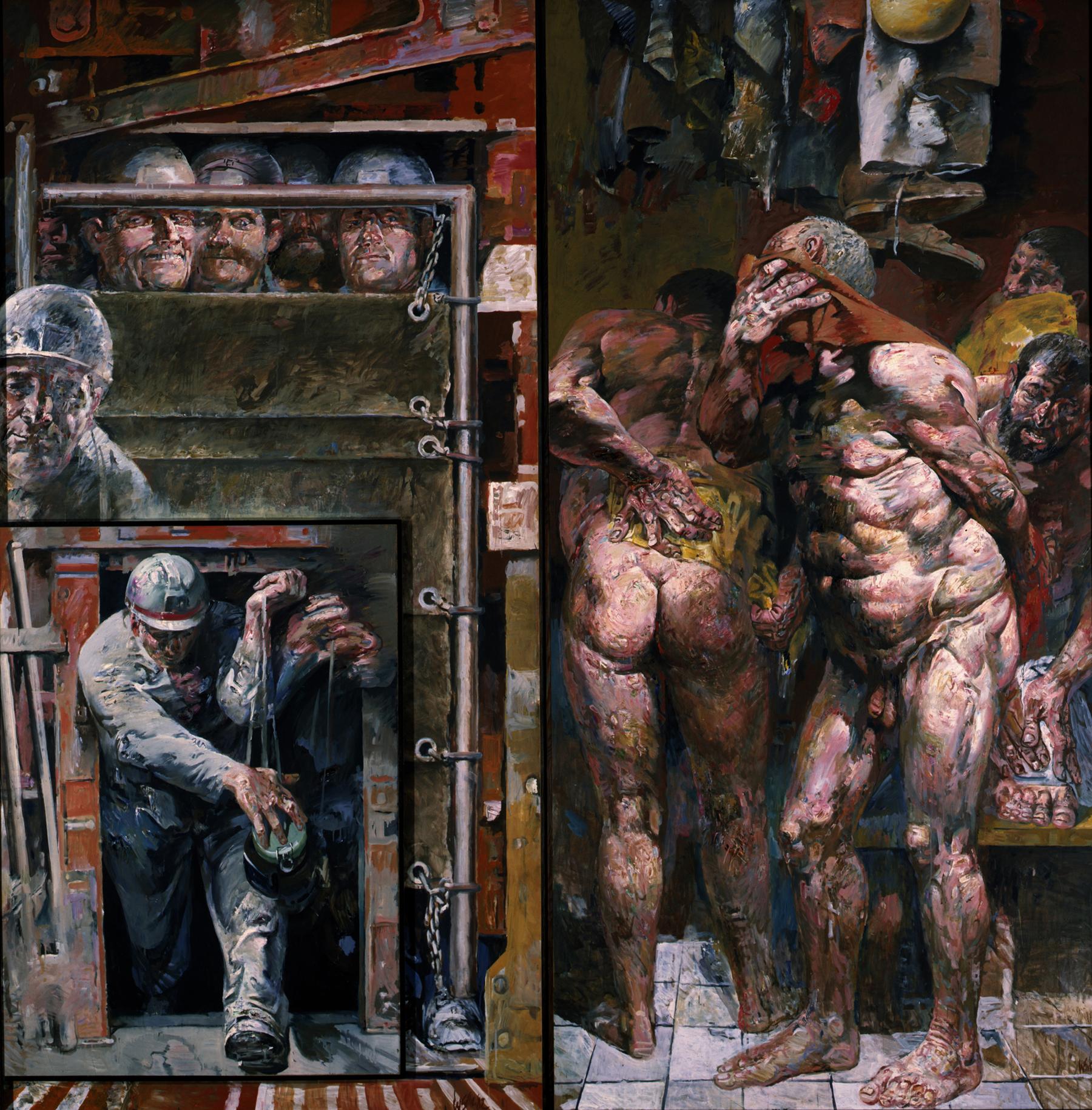

A lot of Social Realist art was awful, yet some artists produced decent art which was still acceptable to the state. One such artist was Willi Sitte, whose biography doubles as a potted history of the GDR. Born in 1921, he studied at the Herman Goering School of Painting and was then conscripted into Hitler’s Wehrmacht. He deserted, joined the Italian partisans and went East after the Second World War, to teach art.

Sitte fell foul of the East German authorities, on account of his fondness for Picasso (who was regarded as bourgeois and decadent by the communists, along with most other modernist artists). Yet in 1953, the year that workers in East Berlin revolted against the communist state, Sitte pledged allegiance to the Socialist Unity Party (East Germany’s ruling party), changed his painting style from modernist to Social Realist, and became a faithful servant of this one party state.

When relations between West Germany and East Germany began to thaw, in the 1970s, thanks to Willy Brandt’s policy of rapprochement (aka Ostpolitik), Sitte’s work was shown in West Germany, where his powerful, accomplished style (reminiscent of Oskar Kokoschka) won high praise. Nevertheless, his inclusion in this exhibition is not uncontroversial. Not only did he become president of East Germany’s Association of Visual Artists, and also a delegate of the East German parliament, after reunification he was accused of being a Stasi informer. Should his work be included here?

At the opening of the exhibition, this question was put to Cornelia Schleime, another of the artists in the show, whose work was banned by the East German government, in which Sitte played such an active part. She replied, commendably, that to ban Sitte’s work now would merely be copying the censorship of the East German regime.

It was an admirable answer, but her own work is the best retort. Born in 1953, a generation after Sitte, after the Wall came down she accessed her Stasi files, and turned them into artworks. "This work could only be realised with the help of the Ministry for State Security and its numerous helpers, who painstakingly contributed to the texts,'’ she wrote, ironically. "To them I extend my thanks.’'

Sitte and Schleime represent opposite ends of the spectrum – one a bastion of the East German establishment, the other a figure of resistance – but for most artists in this show, life in the German ‘Democratic’ Republic wasn’t so clear cut. Born in 1899, Wilhelm Lachnit was imprisoned by the Nazis on account of his “degenerate’’ art. After the war, he became a professor at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, but his art was criticised by party bigwigs. His art wasn’t overtly subversive but it still attracted disapproval. Its sombre mood was at odds with the triumphalist requirements of the state.

Werner Tübke was another artist whose paintings were deemed insufficiently optimistic. He was commissioned by the East German state to paint a big picture celebrating the Peasants Revolt of 1525, but the result was regarded as too gloomy. It was not enough to paint the correct subjects in the correct style. Paintings also had to be upbeat. Tübke cut the painting in half and then hid it away. The two halves are on display in this exhibition.

Elisabeth Voigt’s relationship with the regime was even more ambiguous. Born in Leipzig in 1893, she studied under the great German artist Kathe Kollwitz. In 1958, she quit the state-run Association of Visual Artists, yet was made an honorary member in 1977. “Burn it’’ she wrote, on the letter she received from the association. “I am not a member.’’ As she said, quite rightly, art should create a stir – politics merely crush the spirit.

Voigt’s comments were echoed by Bernhard Heisig, who studied art at the Leipzig Kunstakademie after the Second World War (during which he fought in a tank battalion and was captured by the Red Army). He became professor at the Leipzig Kunstakademie and ended up its director, but resigned in 1964 after years of hostility from cultural functionaries. In 1976 he returned to his old role, but remained critical of the regime’s prescriptive attitude to art. “Art is not an illustration of politic concepts,’’ he said (he also said, astutely, that whenever it tried to be, the results were invariably bad).

These figurative painters could usually scratch a living, so long as they weren’t directly critical of the regime. The artists who were really ostracised were those whose styles were more avant-garde. Abstract artist Hermann Glöckner was marginalised, and surrealist Gerhard Altenbourg was forced to abandon his studies, due to his “amoral choice of motifs’’.

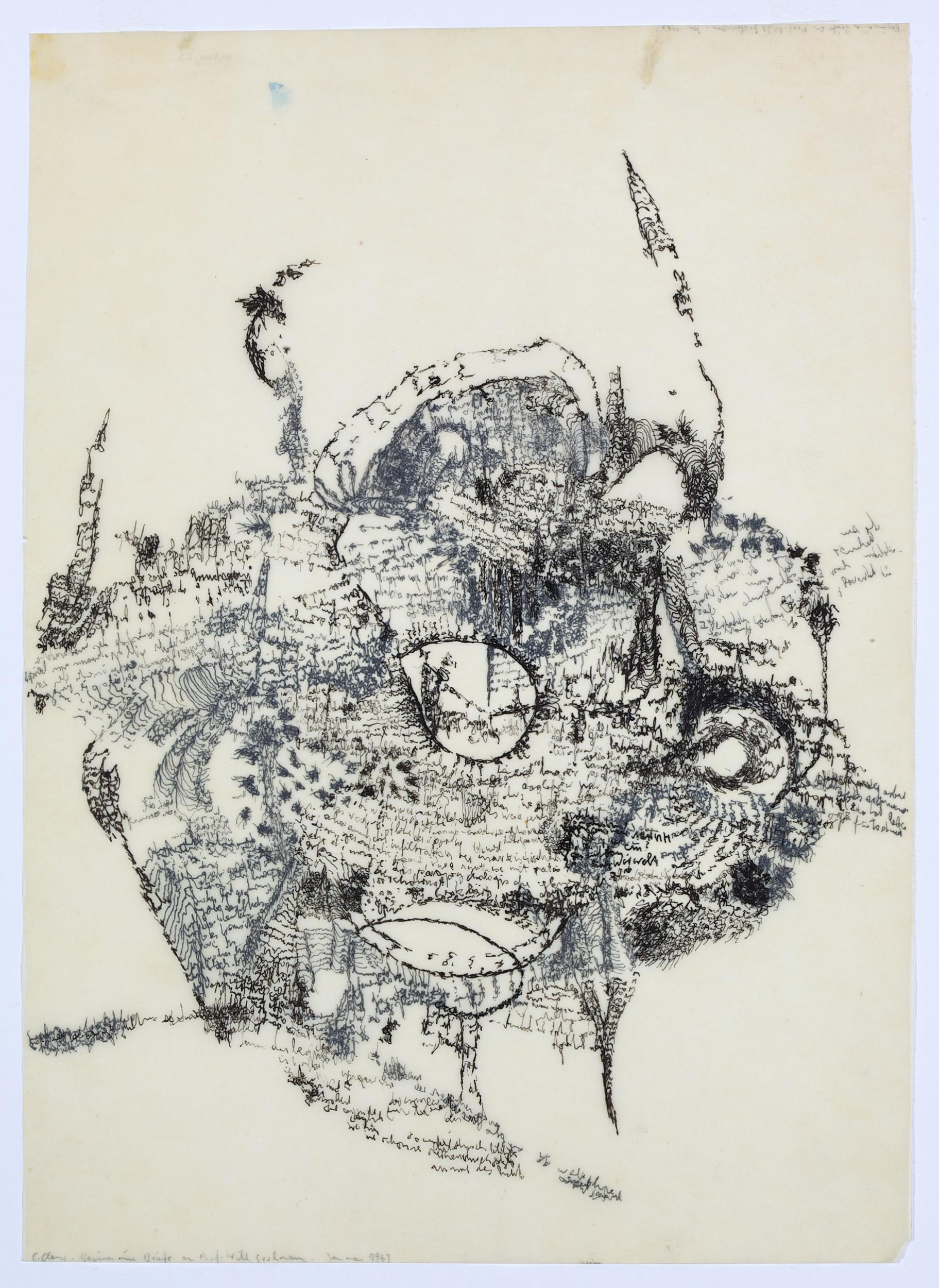

Carlfriedrich Claus was barred from the Association of Visual Artists, and thus prevented from publishing, selling or even exhibiting his work. His crime? His artworks bridged the gap between visual art and music, a form of experimentation unacceptable to the regime. Yet Claus remained a committed communist. It’s these paradoxes which make this such a fascinating show.

“It’s not black and white,’’ says Felix Krämer, over coffee at the gallery the next day. “It’s much more complicated.’’ Krämer grew up in West Germany but he travelled to East Germany as a teenager with his father, a journalist with access to the GDR. “I knew that this wasn’t a happy state, but nevertheless there were a lot of happy people there.’’

As Krämer says, it wasn’t as simple as a straight choice between Western freedom and Eastern oppression. There were also restrictions in the West. "To have that freedom to do what you want, you had to have the money. So if as an artist you don’t sell, you can’t feed your family, you can’t feed yourself – you can’t pay your rent.’'

The artist who personifies Düsseldorf’s close relationship with East German art is Albrecht Penk. Born 1939, at the start of the Second World War, he died two years ago, a renowned figure in the German art scene. Yet as a youngster in East Germany he was unable to get a place at art school. He did odd jobs to support his painting, which he could only do in private, on account of his simplistic style.

Subjected to surveillance and numerous restrictions, he fled to the west and ended up as a professor at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, around the corner from this exhibition. Today it seems absurd that he was persecuted, simply on account of his artistic style, but his story sums up the inherent absurdity of East Germany – a country riven with paranoia which imprisoned its own people and eventually collapsed under the weight of its inherent contradictions. At the time it seemed the GDR might last forever. Looking back, it seems incredible that it lasted all of 40 years.

Utopie and Untergang (Utopia and Decline). The exhibition is at the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf until 5 January 2020. For more information about the exhibition visit www.kunstpalast.de and about Düsseldorf visit www.duesseldorf-tourismus.ded

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks