Should old age burn and rage against the close of day?

For poets, it seems, you have to fit into one camp or the other: to be, or not to be. For Dylan Thomas it was certainly ‘to be’ – but was he right to rage against death, wonders Andy Martin

Do not go gentle into that good night” has some claim to being one of the most famous – perhaps even beloved – poems in the English language. It provides the theme to Christopher Nolan’s wonderful film, Interstellar. It gets a shout-out in Doctor Who, Independence Day and Family Guy, not to mention any number of songs. The poet Paul Muldoon reckons (no doubt speculatively) that it is read at two out of every three funerals. It’s practically the equivalent of singing “happy birthday” where funerals are concerned. Which clearly makes little sense, given that a funeral would by definition involve a person who is in fact already dead, whereas the poem, if it is doing anything, is urging you not to die. Don’t go! If I was at one of those funerals – always assuming it’s not mine – I would be saying: “Isn’t it a bit late for that? That boat has sailed.”

But more than that, I think this poem is so wrong it’s messing people up. Like so much great literature, its utility, as a source of practical advice, is either nil or negative. At best, it’s the expression of a mood. For one thing I can’t imagine why it would ever be read at a woman’s funeral. Women do not feature in this poem at all: it’s all about men. Quite literally (and patriarchally): the word “men” comes up no less than four times in the 19 lines: we have “Wise men”, “Good men”, “Wild men”, and “Grave men”. Of women, there is no sign. Don’t they die too?

But wasn’t the poem addressed to his dying father? A hypothetical father figure comes up in the poem (“there on the sad height”) but Thomas was writing this in Florence in 1947 and his father (who was certainly ill) didn’t die, in Wales, until the end of 1952. More likely the poet was addressing it to himself, because if anyone had a powerful death-wish it was Dylan Thomas.

His widow, Caitlin Thomas, wrote that “Dylan had this rather odd view that all the best poets died young and that he himself would never make 40, and there were times when he almost seemed to live his life by that”. As it happens he was 39 when he died, in New York, in 1953. He was no great fan of longevity as such. He had drunk himself into a coma, having first uttered the immortal line, “I’ve had 18 straight whiskies. I think that’s the record”.

When Caitlin (who definitely was “raging”) arrived at his death bed, she reportedly asked: “Is the bloody man dead yet?” Thomas had adopted the persona of the “roistering, drunken, doomed poet” that was always likely to kill him. It is possible he felt some degree of guilt at having ducked active service in the Second World War, getting himself rejected on medical grounds with an epic hangover. So if he was “raging” against anything – “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” – it was himself.

I have no argument with champions of Dylan Thomas who want to say that he wrote great poetry. I have to acknowledge his mastery of form – here, the villanelle, skilfully orchestrated, with its refrains and only two rhymes (“ight” and “ay” spun across 19 lines). I’ve always been a fan of those poems of his, like “Fern Hill” (“And I was green and carefree, famous among the barns”), that are life-affirming nostalgic evocations of a Welsh childhood. But Thomas is a poetic extremist, a fundamentalist, with none of the nuances of, say, Eliot or Auden or Larkin. Everything he wrote was hyped-up and rhetorical to the point of madness and absurdity. But most of all when he came to writing about death.

Probably all literature revolves around the great question, to be or not to be. Dylan Thomas declares himself (for the purpose of the poem) of the “to be” school of thought. This is so reasonable as to be a basic premise of life. Clearly George Floyd wanted to breathe, otherwise he would not have complained (to the man who was slowly killing him), “I can’t breathe!” By the same token, if you get taken down by Covid-19, and your lungs are starved of oxygen, you will want to keep breathing more than ever. If you can breathe, then breathe.

But do you always, and at any costs, and at any age, “rage against the dying of the light”? Do you require immortality? Thomas may be focusing on that phase of life we describe as “death throes”, suggesting some kind of violent struggle.

“Do not go gentle” is so much a man’s poem it hints at those classically masculine tropes of fighting the good fight and going into battle against some kind of invisible enemy (which is in fact your own body running out of steam). If I can get away from fathers and consider the case of my own mother, did I want her to go out, a few years back, in a fit of death-rage? No, not really, any more than I felt that “old age should burn and rave at close of day”.

![Our impulse ‘is to fight [death], to die with chemo in our veins or a tube in our throats or fresh suture in our flesh’](https://static.the-independent.com/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2020/07/16/15/Burial-chambers.jpg)

She was in her nineties and had lost command of her own life. When I watched her in hospital one long night, hooked up to a ventilator, and hanging by a thread, it became obvious to me that sometimes your body is struggling to die, not to live. I authorised the doctor to administer more morphine and alleviate the pain at the risk of abbreviating her life. Do go gentle.

Post-Shipman, the medical profession lives in fear of being sued for engineering death prematurely. But sometimes engineering life, extending it artificially, through the application of technology, is not so much pointless as cruel. It has to be about quality of life as much as quantity. As the surgeon Atul Gawande argues in Being Mortal, “our every impulse is to fight, to die with chemo in our veins or a tube in our throats or fresh suture in our flesh. The fact that we may be shortening or worsening the time we have left hardly seems to register.” When it comes to the end of his own father, he “worried most about the mistake of prolonging his suffering too long”. And even his father says: “I’m thinking how to not prolong the process of dying.” He was beyond rage.

The medical profession lives in fear of being sued for engineering death prematurely. But sometimes engineering life, extending it artificially, through the application of technology, is not so much pointless as cruel

In the “not to be” corner, we have, above all, Socrates. When Keats opens his “Ode to a Nightingale” with the lines, “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains/My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,” he is recalling the death of Socrates. The philosopher had been condemned to death by a court in Athens for corrupting youth with his ideas and not believing in the gods. There was no First Amendment in Fifth-Century BC Athens. The “security” of the state took priority over individual freedoms. Contrary to the wishes of his followers, who were ready to spring him from prison, Socrates willingly, calmly, chose hemlock and he felt his body freezing from the toes upwards, thus enabling him – unlike my mother, for example – to rhapsodise about death even as he was dying.

Personally I would have done a runner, if I could. I would normally vote to postpone death and, in that sense, rage against dying. But Socrates was surely right to try to overcome our natural fear and trembling in the face of death and seek serenity. It could be said though (to draw on Keats again) that he was “half in love with easeful death”.

Socrates – and his disciple Plato – took the view that since life was so radically imperfect, there must exist some alternative sphere of perfection, in which the long sought-after epistēmē of knowledge and eternal truth was to be attained. Nothing in life quite measured up to the purity of concepts and geometry and therefore death must be their domain. Before life and afterwards were both fine, it was the bit in the middle that was the problem. The true philosopher, Socrates reckoned, would naturally gravitate towards death. When Socrates said, “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius” (the god of healing), he was saying that death will cure all ills.

Rage against the dying of the light or “tender is the night”, as Keats has it? Keats was dead (of tuberculosis) by the age of 25 and it was probably the tradition of the deceased Romantic poet that led to the James Dean theory of live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse. There must be circumstances where the modern equivalent of hemlock and the one-way ticket to Switzerland (or, in my own case, Montana) is justified. But more often than not the Grim Reaper will be unwelcome.

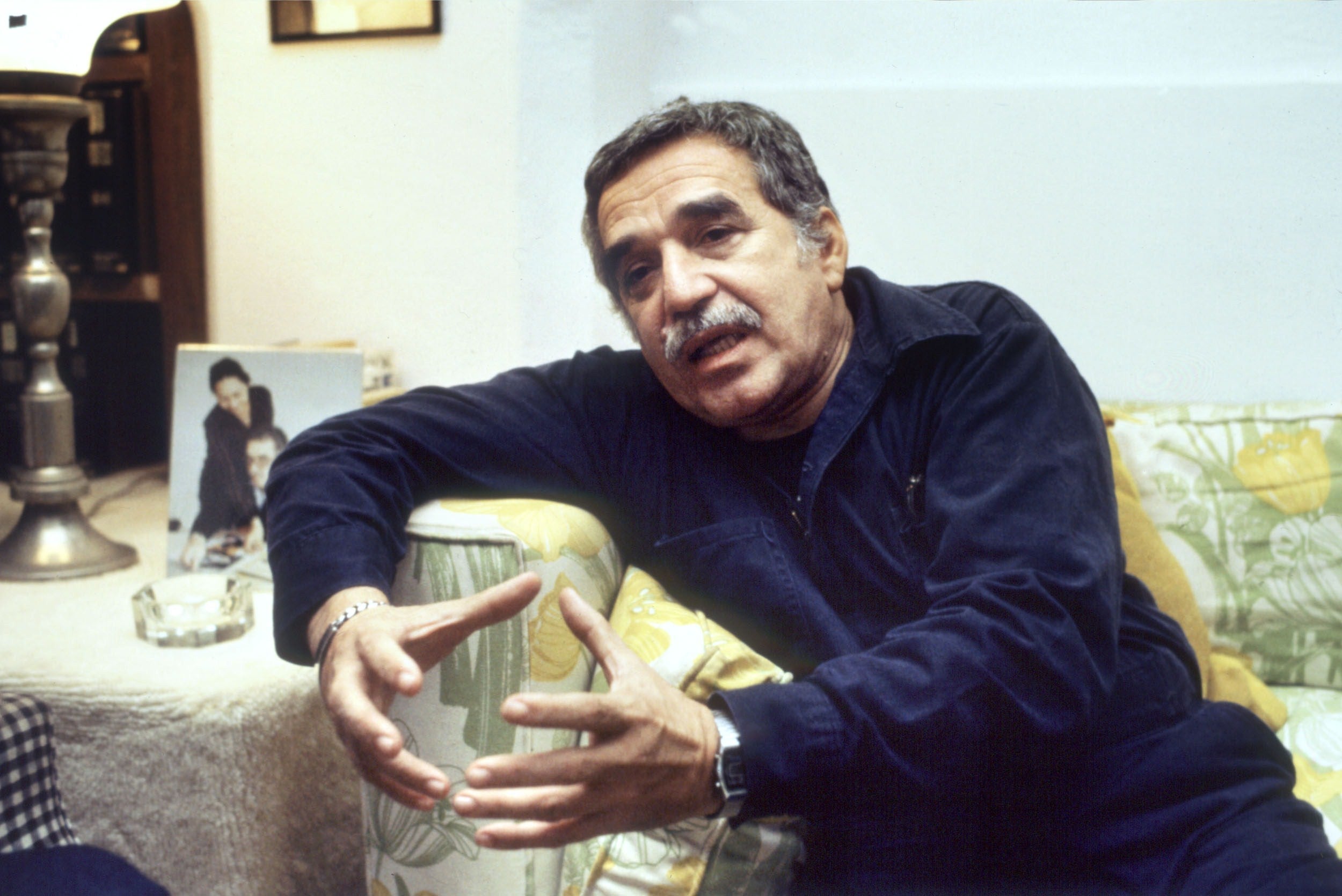

In the midst of “mass termination”, as a friend in New York neatly summarised the reign of Covid-19, I have recently been reading Love in the Time of Cholera by the Colombian Nobel prize-winning writer, Gabriel Garcia Marquez (translated by Edith Grossman). In the original Spanish, cólera can mean “rage” as well as the disease.

Marquez himself lived to the age of 87. With, I can’t help noticing, a decent head of hair (and flourishing moustache). This strikes me because one of the torments that he puts his hero Florentino Ariza through is to have all his hair fall out at a relatively early age. He battles in vain against baldness, trying out 172 infallible cures. And then his teeth fall out – or he has them all taken out – and relies ever after on false teeth. But he has to keep on going because he is still in love with Fermina Daza.

He fell in love with her while still a beardless youth, and she (it seems) with him, then she drops him completely – “Forget it!” – and marries a doctor who has a bad habit of falling for his patients. The decades roll by but Florentino never wavers (although he has countless love affairs to try to forget, if only for a while). For over half a century (“fifty-one years, nine months and four days” – he knows exactly), he persists in love.

For anyone in the second half of their life, Love in the Time of Cholera is going to be a disturbing read. Florentino is barely into his fifties before he is described as having “crossed the line into old age” (another character is “sinking into the quicksand of an unfortunate old age”). He is starting to look like a vampire (not one of those good-looking young vampires). That naked scalp of his “emits a phosphorescent glow in the dark”.

I kept on thinking as I read the book that, realistically, Florentino ought to give up. His obsession is ridiculous, verging on immoral. Fermina had given no sign of any lingering interest in him, beyond pity. But, against all reason, he refuses to let it go. Does he rage against death or desire it, to put him out of his misery? At a certain point he is stricken by “a thunderbolt of panic that death, the son of a bitch, would win an irreparable victory in his fierce war of love”. It becomes a race between death and love to see which will win.

There is a madness to Marquez without doubt. Perhaps no one in their right mind would keep that one-sided flame burning for so long in the face of chilly indifference. But Marquez also pinpoints love for someone or something beyond yourself (and it could be the love of an idea, like Socrates, or the planet, or cooking, or jogging) as the only basis for – as per the Beegees – “stayin’ alive”.

“The body carries on for as long as you do,” as he puts it. For Marquez, love not rage is the best formula for longevity. Especially when unrequited.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Surf, Sweat and Tears’ (published by OR books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments