The death of the author

We should never have ascribed godlike powers of creativity to writers. They are just content generators... and that’s not new. The reader has always called the shots, explains Andy Martin

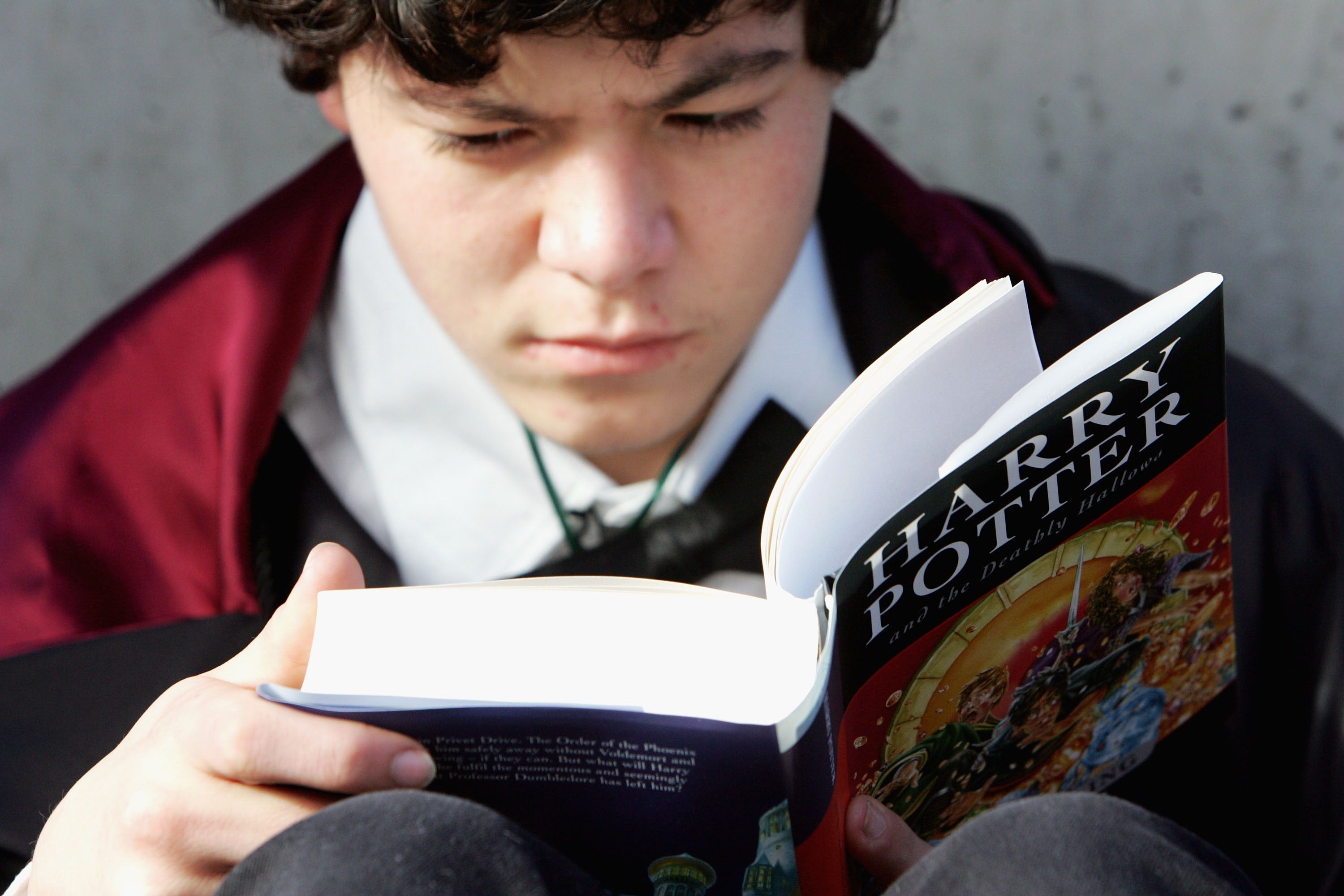

JK Rowling is a lot of old Hogwarts. Not just because she picked on an old school as the setting for her stories of witches, wizards and assorted archaic absurdities. It’s more that she went down the traditional well-trodden track of finding an agent and publisher. According to legend, she put her submission to the agent in a bright pink envelope so it would garner attention and be duly salvaged from the slush pile. And it would then, in the classic manner, be rejected over and over again by blinkered fools (who perhaps have been required to commit publishing hara-kiri) before finally being accepted by Bloomsbury. Many writers, also using the garish envelope technique, sometimes with added glitter, have tried to follow. But the Rowling model is now about as antiquated and irrelevant as flying broomsticks.

Consider the case of Andy Weir, author of the bestselling The Martian, made into a film by Ridley Scott starring Matt Damon. He wasn’t even a writer, he was a software engineer in Silicon Valley. But he had a notion of getting a book out there and even tried his hand at going down the traditional route in the 1980s: agent? No thanks! Publisher? No way! But he carried on jotting in his spare time regardless.

With the internet up and running in the 1990s, he set up his own website and posted a few stories online. He emailed them to people. One of his stories was about a mission to Mars. Assuming it all went wrong, how would you survive? He tried to work it out and would post a chapter every now and then. Readers, often of a technical inclination, would write back to him, offering corrections or alternatives.

Weir would try to fix the physics or the chemistry. He finished it but readers wrote to him asking him to make it into an e-reader format. So he did that. Then someone else asked for a Kindle version – he did that too. He chose the lowest price Amazon would allow – 99 cents. Weir could hardly believe it when more people bought the Kindle book than the free one he was offering – and he saw it climbing up the Amazon charts until it was number 1 in the science fiction category.

Then he got the email. “I think we could get your book into print and if you don’t have an agent, I’d like to represent you.” From an agent. They were contacting him, not the other way around. “I’m like, wow,” says Weir. After that it snowballed. Random House put a pre-emptive offer on the table. “It was a no-brainer – it was more money than I make in a year in my current job, and that was just the advance.” And it was not long before Hollywood came calling. Weir remains modest and genuinely dumbfounded by the sequence of events. From blog to blockbuster. From his laptop to sales in 31 international territories. The Martian had conquered Earth.

Sociologist John Thompson went to meet Weir, and records this tale in the opening chapter of his magisterial new Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing. He concludes that “the very changes that had enabled Weir to realise his childhood dream were wreaking havoc in an industry that had operated in pretty much the same way for as long as anyone could remember”.

Weir got started (at the age of 9) by writing “fanfiction”, riffing on works he loved. So too EL James (or Erika Leonard), she of Fifty Shades of Grey. She was a fan of Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight vampire series, so she started posting the further adventures of Edward Cullen and Bella Swan on the fanfiction website, FanFiction.net under the pen name “Snowqueen’s Icedragon”.

It used to be that writers would write and readers would read: writers would quite literally tell the reader what to read. No longer

But the stories were too erotic for FanFiction.net’s taste, so she took them off to her own website, 50Shades.com, ramped up the sadomasochistic content and renamed her characters Christian Grey and Anastasia Steele. The first version of the trilogy dribbled out in 2011 through a small Australian publisher until, after orgasmic social media attention, it was picked up (yet again) by Random House and republished in 2012. The books sold more than 125 million copies worldwide. And if the associated Hollywood bonkbuster earns you more than a billion dollars at the global box office, really, who even cares about the reviews any more?

Harry Potter, The Martian, and Fifty Shades: all phenomenally successful, all genre fiction, all multi-media. Rowling no doubt remains the standout in terms of sheer productivity, sales stats, and now multiple identities too (having been revealed as the woman behind the Strike tec series by “Robert Galbraith”). But she is also the throwback in terms of her publishing paradigm, she is the anomaly, while Weir and James exemplify (in a stratospheric way) a significant evolution in the contemporary scene.

Novels are not just read any more, they are reader-led, reader-driven, colonised and compromised by readers, prior to publication. It used to be that writers, selected by agents and publishers – the so-called “gatekeepers” of the industry – would decide what we were going to read. They don’t any more: readers do.

“It’s something Amazon understood early on,” Thompson said when I spoke to him recently. “Except they don’t call them readers any more, they call them customers.” Amazon, or its algorithm, knows what you like and is determined to ensure you get more and more of it.

But there are other websites out there, beyond Amazon, beyond FanFiction.net, where the future of fiction is currently being played out. In the UK, Unbound offers a form of crowdfunding for projects, so too Inkshares in the US. In Toronto, Sophie, who is in charge of “content production” at Wattpad (as reported by Thompson) says: “We let the crowd decide.” In 2019 Wattpad had 80 million users worldwide and boasted more than 565 million story uploads (and has morphed into Wattpad Books and Wattpad Presents). This is not an exercise in “self-publishing”. To all intents and purposes, the “self” has ceased to exist at Wattpad.

Online, there is no more wandering lonely as a cloud. It used to be that writers would write and readers would read: writers would quite literally tell the reader what to read. No longer. At Wattpad writers and readers co-exist on a plane of intimate interaction and reciprocity.

As in the entanglements of Fifty Shades, it is hard to know who is doing what to whom. The very notion of “authorship” is eclipsed by the network or community and the old gatekeepers are removed from the equation. Wattpad is accessed predominantly by mobile devices and from now on stories are (literally) “phoned in” and “chatted” into existence. “The social media component is not an added extra but is integral to the writing process,” says Thompson.

Using my phone, I had to divulge some personal information to get on to the website. I said that I “write mainly for fun” (which is true, mainly). I was interested in “adventure”, “contemporary fiction” and “fanfiction” – and now I’m starting to read Break Open by Lisa H. “Years ago,” runs the standfirst, “their hearts broke. He’s now ready to pick up the pieces. She’s engaged.” There is a warning that I’m about to get “sexual content, violence and coarse language”. I’ve got to admit, I’m already hooked, even though I don’t exactly fit the Wattpad demographic, which is predominantly (but not exclusively) teenage girls.

But now I’m logged on I get to “vote” on stories and make comments, even while they’re being written (Lisa H has had 69.8k reads and 3k votes – and there are already 25 “parts” to her story). I find there are other readers out there, such as “ilikeemrealnasty” and “cluelesslyobsessed” and “sexybookwormlover” scribbling comments or more likely emojis in the margins.

Ironically enough the story concerns (in part) a character who is fighting for a certain publication “in an atmosphere that was hostile to anything in print, and only welcoming to easily digestible digital media”. I haven’t quite got into this yet, but if I click on “paid stories” I can “thank writers for creating the stories you love by monetarily supporting them”. So I can pay them (using “Wattcoins” moreover) as well as vote for them, if I like their style.

This is the future of publishing ... the readers are orchestrating writers, pulling their strings, shaping the books to suit themselves, not being dictated to any more

Roman tightens his jaw (in Break Open). “I love it when men tighten the muscle in their jaws – I just find it so sexy,” says KaylaMVibes. Not everyone is crazy about it when he snubs Jade though. “Well shiet,” says Redstories. It gets a simple “No” from mbalientle24 with a skulls emoji. On the other hand, “I love the way u wrote this” says asdfghjkl123455553 when Nina and Roman bump into one another at the bar and sparks fly.

When it comes to the TV and movie studios who pick up Wattpad content, they can “leave out Jade (or whoever) – nobody likes her!” The cuts are backed up by the data. And there is a ready fan-base for adaptations. Thompson makes clear that this is the future of “publishing” – the readers are, in effect, orchestrating writers, pulling their strings, shaping the books to suit themselves, not being dictated to any more. The author becomes a mere supplier, their works determined and validated by demand not by sheer genius. We let the crowd decide.

But this is not just the future, it’s the ancient past too. Consider the case of Homer, for example, the “author” of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Homer did not exist. Homer is a convenient label for the generations of oral performers who told and re-told stories of great Greek heroes whose origins were remote and lost in time.

Epic poetry is a compendium of loosely connected oral-formulaic compositions. The original recitation that the subsequent texts were based on had to be delivered if not around a campfire at least in a finite public or private domain where a crowd could hear a single speaker. Theatre, largely scripted, was a natural extension of this archetype. But in its original form the pre-literate “text” or tale was subject to variation and improvisation according to the requirements of the crowd: “Tell us another one about Odysseus/Achilles/Helen!”

The performer of these stories became known as “Homer” or “homeros”, meaning “hostage”, because this close encounter involved not so much a captive audience as a captive writer who was not allowed to be freewheeling and imaginative but rather skilled in satisfying the requirements of the mob, always potentially violent. Plato suggested banishing Homer (and other poets) from the city, but I have no doubt that some of these earlier homers, after running up against the zeitgeist (rather like Trotskyists in Stalinist Russia), trying to be more like “authors”, will have met a bloody end. It was the primal “death of the author” (in Roland Barthes’ resonant phrase).

EO Wilson, the father of biodiversity and sociobiology, argues (in his Origins of Creativity) that the oral starting point of storytelling must be something like the stories about hunting that are told by the Ju/’hoansi bushmen of the Kalahari. In these pre-Homeric epic adventures or “firelight talk” hunters regale other hunters with stories about the hunt.

This is one about taking down an antelope with a poison arrow:

Wandering bards could never have wandered too far from a pre-existing script, not unless they wanted to incur the wrath of their most powerful listeners

“He’s safe, he thinks. He turns around. I am behind him. I creep forward, eh! I creep I creep, I am just that far, eh! Just that far from me to there, quiet, quiet, I’m quiet, I’m slow, I have my bow, I set the arrow. Ai! I shoot. Waugh! I hit him! He jumps. Ha ha! He jumps! He runs. He’s gone! I shot him. Right there, just here the arrow went in. He jumped, he ran that way, going that way, but I got him.”

This is the verbal equivalent of neolithic cave paintings. There is, in effect, no distance between “writer” and “reader”: the creators and consumers of these elemental narratives are one and the same, switching places, bouncing stories from one to another in a spontaneous network in which there are only nodes, RTs, recollections of prior performances, and no discernible originary transmission. At night (as Elizabeth Marshall Thomas points out in The Old Way: A Story of the First People) the night-time fireside stories are more fantastical than in the more practical “daytime talk”.

Wandering bards could never have wandered too far from a pre-existing script, not unless they wanted to incur the wrath of their most powerful listeners. The idea of appending your name to any of these early epics will have seemed absurd and without justification even to the most skilled. “Homer” was not just blind – as an early tradition had it, and therefore incapable of either reading or writing – but devoid of any identity.

The author was always anonymous. Think, for example, of those quite literally “timeless” works, since they cannot be tied down a specific point of origin, like Gilgamesh – the Babylonian epic and palimpsest and compilation of Sumerian poems, bearing the trace of many hands and assorted languages and bearing only a title not the name of some self-assertive author figure (Gilgamesh himself was in some version “Bilgamesh”).

So too Beowulf, handed down in Old English, one of the founding works of what can loosely be referred to (in a rather preening, narcissistic and perhaps obsolete way) as “English literature”, even though exclusively concerned with the ancient antics of militant Scandinavians. I’m currently reading the new and very colloquial translation (“hashtag: blessed”) by Maria Dahvana Headley that opens not with Seamus Heaney’s “So…” but rather “Bro…”, implying a circle of predominantly male narrators and audience.

The text as we have it now is a tapestry (or “mashup”) of discrete tales that weave into one another – rather like a “set” performed by a DJ in our day, which will be made up (as one musician explained to me) of “bangers” together with one or two “tunes” that the DJ might have conjured up to hold them all together. I am reminded that another of the hypothetical etymologies of “Homer” is “he who fits the song together”.

Nobody sees Jesus post-crucifixion. Rising from the dead ... is a classic writerly response to popular demand: You can’t just let him die! OK, then, well what if he rises from the dead – and will return? That way we have the possibility of a sequel

The post-literate and the pre-literate converge. I am going back to Beowulf because I am sick of our lingering over-emphasis on the concept of the author, our idolisation of a myth. The “traditional” model of the author-reader relationship is in fact a recent invention and doomed, I hope, to fade away. It is JK Rowling that is the anomaly, not the Weirs and James’s of this world. And how did the “author-function” even begin? Partly, I surmise, out of questions like: how did it all begin?

Bereshit, the first word of the Book of Genesis: “In the beginning…” (which should perhaps be better translated “In a beginning…”). We expect everything to have a point of origin. “Once upon a time”, “Il était une fois” and no doubt in many other languages too: we assume a singularity. But as the wise Jorge Luis Borges writes: “It was the first night, but several centuries had already preceded it…” It probably began with homo faber. We started making things, which gave us the idea that everything needed a maker, including the makers. Hence the concept of the Maker. Soon it was not enough to have a genealogy (“begat… begat… begat”), there had to be a Genesis story too – we had to fill in the gap at the very beginning, to extrapolate backwards.

As soon as we had a God for a hero, so too heroes tended to become more godlike. And “authors” alongside them, garnering some of the credit and glory they attributed to their characters. We went from God the Creator – Babylonian tales overlapping with the myths of Gilgamesh – to individually named evangelists.

Authorship is inseparable from miracle-working, walking on water, and resurrection. The first draft of the gospel according to Mark, the oldest gospel, omits the virgin birth and witnesses to the resurrection. Nobody sees Jesus post-crucifixion. Rising from the dead – as in the case of Sherlock Holmes recovering implausibly from the Reichenbach Falls episode – is a classic writerly response to popular demand: You can’t just let him die! OK, then, well what if he rises from the dead – and will return? That way we have the possibility of a sequel.

Read More:

The practical daytime story (he died on the cross) turns into a firelight talk (but he lives again). Or, fast-forwarding to JK Rowling, what if we have witches and wizards and magic wands? All modern super-heroes are mutant forms of myth or religion, a contemporary form of the opium of the people.

It’s a pity we ever ascribed godlike powers of creativity to writers – they’re just content generators. Rowling and Weir and James: like the troubadours of old, and the contributors to Wattpad of today, they were only ever giving their audience what they wanted to hear.

The most successful writers of all, like James Patterson and Lee Child, don’t even write any more – they leave it to their most dedicated readers to do the job for them and content themselves with banking the cheque. They have become brands. It’s a mistake to think of writers as gifted individuals – do we ever imagine that a certain Mr McDonald made that burger or that Ben or Jerry made that icecream?

John B Thompson’s ‘Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing’ is out now (Polity Books)

Andy Martin is the author of ‘With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher’ (Polity Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks