How do dictators retain power, even when reviled and mocked by those they govern?

Modern-day despots wish to be blessed for their extravagant genius. But, Robert Fisk asks, what are we to make of this lunacy? And do they really believe their own hype?

Alaa Al-Aswany is a good guy. Romantic – far too romantic – about revolutions. And almost facile in his willingness to believe that generals in sun-shades who depose elected presidents can at first be trusted. But I’m not surprised that Egypt’s master-writer has now decided that dictatorship is a syndrome, a medical condition that can even be diagnosed – but not, I fear, cured. Aswany, I should add, is also a member of that profession which I find most terrifying: he is a dentist. A good man, then, to work away on the decaying teeth of the Egyptian revolution.

His latest work, The Dictatorship Syndrome – albeit less powerful than his novels (read The Yacoubian Building, if no other), which froth with veracity – is thus going to further enrage President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt, who toppled Mohamed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood official, in 2013. Sisi was pretty fed up with Aswany after his previous book, The Republic, As If came out. “It’s about how a dictatorship looks ‘as if’ it is true,” he told me back in 2014. “With fair elections, [government] departments, and so on – ‘as if’.”

Not long after we met then, Aswany was banned from publishing his weekly column in Egypt and from appearing on official media. He remained a permanent critic of the Brotherhood but, asked in October 2018 if Sisi was the same as Honsi Mubarak – overthrown in the popular uprising of 2011 – he said that the Sisi regime was “worse because today’s [Sisi] dictatorship is a wounded tiger. A wounded tiger is much more dangerous. The tiger has confidence in itself, he knows he’s strong and therefore has no need to attack anyone. The wounded tiger will never forget that he has been wounded and that he risks receiving an even more serious wound. He attacks everyone.”

In the spring of 2019, the tiger attacked Aswany. He was now also forbidden by state security to speak at public seminars. But when he criticised the regime’s nepotism and corruption – for appointing senior army officers to civilian posts – Sisi took it personally. Aswany, who had by this time judiciously moved to the United States, found himself charged by Egyptian military prosecutors “for insulting the president, the armed forces and judicial institutions”. “My only crime,” Aswany retorted, “is being an author, expressing my opinion, and criticising those who deserve it, even if it’s al-Sisi.” Addressing the Egyptian military prosecutor, he added that “if my crime is to openly express my thoughts, I recognise that and am proud of them.”

I recount this only because, in much earlier days, Aswany was far less critical of Sisi. After the destruction of the Mubarak regime in 2011, he met Sisi at the Military Service building in Cairo. “I had written an article against Tantawi [still then commander of the Egyptian army] which Sisi didn’t like. I said to him [Sisi] that I had the right to write what I thought and told him he could arrest me if he wanted. He told me he wouldn’t arrest me and was very friendly. I had the impression he didn’t necessarily agree with the decisions of Tantawi. I had a good impression about al-Sisi. I thought I could trust this man.”

And so, of course, did millions of Egyptians. In a newspaper of the time, Aswany totally accepted the utterly false figure of 30 million Egyptians on the streets protesting at Morsi’s rule and calling for the army’s (and, by extension, Sisi’s) protection – a statistic, he wrote, which “caused the army to take a great patriotic stand for implementing the will of the people and preventing the fall of the state.” This had been, he said, “one of the greatest achievements of the Egyptian people”.

The highly esteemed and veteran Egyptian journalist, the late Mohamed Heikal, initially took the same view of Sisi, although he began to withdraw his support shortly before his death almost four years ago. So did MP Anwar Sadat, nephew of the assassinated ex-president, who soon had his wings clipped by Sisi. But all this raises an important question: is dictatorship really a disease, as Aswany maintains in his new book?

I fear those most afflicted – and those whose behaviour is more worthy of medical examination by Aswany and his friends – are the millions who not only obey the dictator’s orders, through fear or corruption, but who actually love the wretched men who rule over them, who write the most awful poetry about them or who express the odious and grovelling mantra which I have so often had to listen to in the Arab world: “With our blood, with our souls, we sacrifice ourselves for you.” How do you move from trust to disgust?

Aswany and his well-educated friends would never make such promises. They are far above the pack of journalists and presenters who showed their new-found love for Sisi after the latter’s coup by appearing on Cairo television in military costumes. The re-infantilisation of the Egyptian people – who had thrown off Mubarak’s thugs only to welcome Sisi’s goons two years later – must have deeper roots. I am always reminded of the Lebanese Kahlil Gibran’s poem The Garden of the Prophet in which he laments: “The nation that welcomes its new ruler with trumpetings, and farewells him with hootings, only to welcome another with trumpetings again.”

My only crime is being an author, expressing my opinion, and criticising those who deserve it, even if it’s Sisi

Is there perhaps a different kind of infection taking hold of a people who submit to a dictator? Could it perhaps be the sickness of patriarchy? The Polish journalist and author Ryszard Kapuscinski wrote Shah of Shahs about the decline and fall of the Pahlavi throne, identifying the very minor and submissive Iranian bureaucrat who, once he arrived at his humble residence, ruled his family with dictatorial venom, visiting upon them the same shah-like patriarchal fear which he exhibited in serving his royal master. Certainly, WH Auden captured the mass insanity and fealty of “the people” so well that many would come to associate his 1939 poem about the tyrant with Saddam Hussein:

“Perfection, of a kind, was what he was after,

And the poetry he invented was easy to understand;

He knew human folly like the back of his hand,

And was greatly interested in armies and fleets;

When he laughed, respectable senators burst into laughter…

And when the tyrant cried the little children died in the streets”

In the west, where we have largely consigned European dictatorships to our empty institutional memory, we can somehow live with present-day dictators who oppress their own people – as long as they are our allies in “the war against terror” or possess vast amounts of oil and natural gas or buy trillions of dollars of our fighter-bombers, missiles and tanks. As an ally of Russia, Assad is still to be denigrated. Sisi, with 60,000 political prisoners, is “my favourite dictator” (Trump) and Saudi Arabia one of America’s most coveted protectorates.

Even European dictators of the last century can acquire a sufficiently buffoon-like status to attract our own excuses. A new book in Italy suggests, in the words of populist right-wing movements, that “Mussolini did many good things before the racial laws and the alliance with Hitler”. It attributes new roads, bridges and the draining of the Pontine marshes to Mussolini, although scarcely 6 per cent of these improvements were the work of the fascist authorities. Retirement pensions, the book says, were the work of Mussolini. Untrue. They were first introduced in 1895. Anti-Jewish laws were implemented as early as 1938.

It is true that modern-day dictators wish to be blessed for their extravagant genius. Sisi’s “new” Suez Canal – in reality a back-double waterway that allows more ships to pass each other in opposite directions but has failed to increase Suez earnings – and a series of new mega-cities outside Cairo might be the Egyptian version of Italian fascism; Aswany recalls how Gaddafi implemented the Great Man-Made River project. Now we have Mohamed bin Salman’s new futuristic mega-city on the Red Sea, a $500bn project which will supposedly include artificial rain, a fake moon, robotic maids and “holographic teachers” (the latter according to the Wall Street Journal). Who now remembers Hitler’s “new” Berlin and his Arctic-to-Sebastopol Nazi motorway?

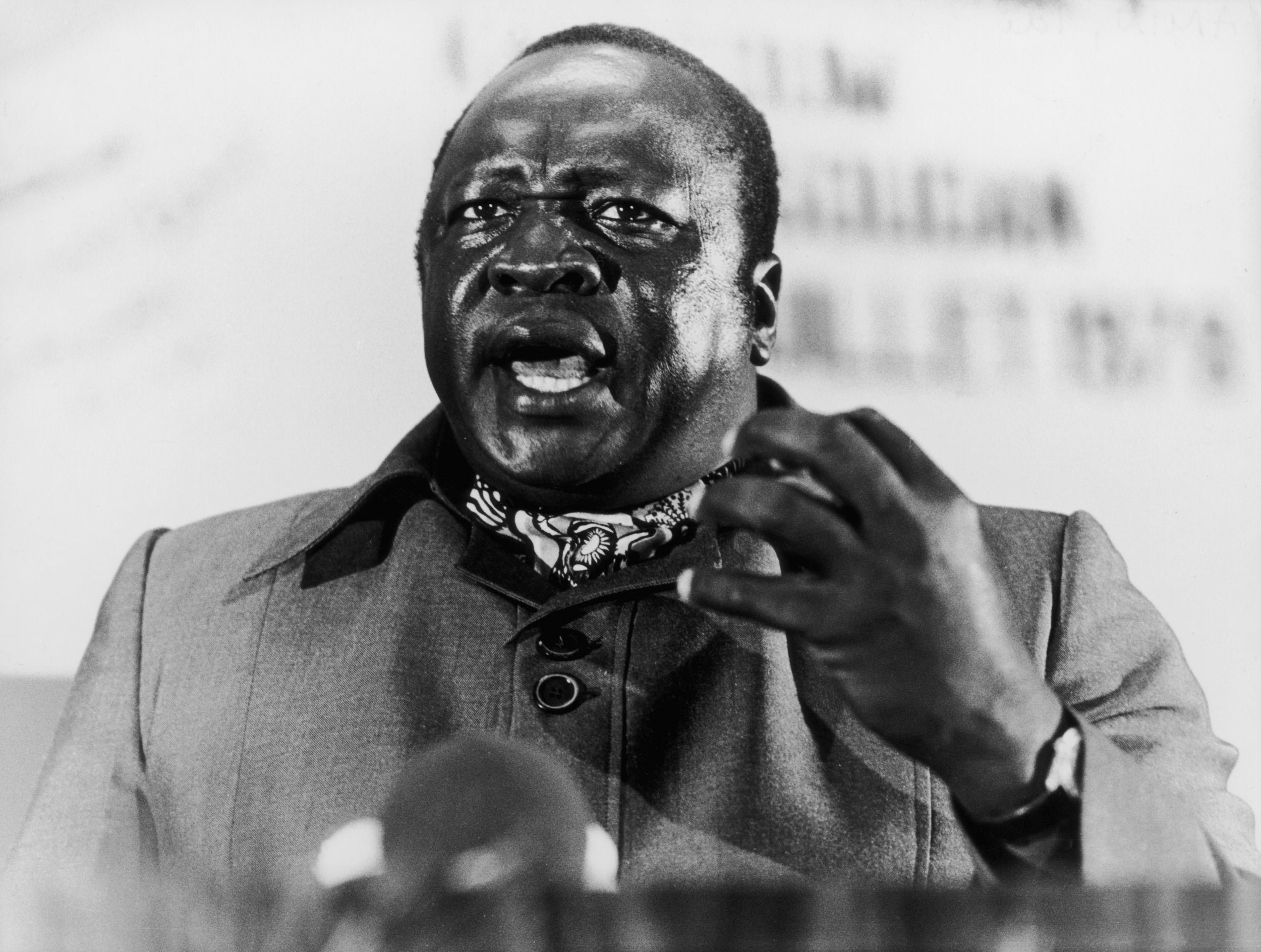

We might also remember Idi Amin who declared himself Lord of all the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular

What is one to make of this lunacy? Do the dictators really believe in their own titles? Gaddafi, Aswany reminds us, was variously called Colonel, Leader, Leader of the Libyan Revolution, Custodian of Arab Nationalism, Dean of Arab Rulers, King of Kings of Africa, Commander of the Tuareg, Leader of the Association of Coastal and Desert States and Leader of the Popular Islamic Leadership and Imam of the Muslims. We might also remember Idi Amin – like Ben Ali of Tunisia, another despot who retired to die in Saudi Arabia – who declared himself Lord of all the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular.

It’s one thing to identify aspects of humiliation and revenge in the families of future dictators but Aswany traces the course of the dictatorship syndrome through the “quest for sole power” to “a lust for glory” to “supreme isolation”. The latter leads to “a bad decision”, according to Aswany – although not often enough, in my view. A tyrant in his multi-delusional world, he says, “is like a person driving a car with no brakes or rear-view mirror. He drives without the least notion of the surroundings he is driving through, and he cannot stop the car even if he wants to ... The car will end up crashing horribly”.

It’s one thing to identify aspects of humiliation and revenge in the families of dictators but Aswany traces the course of dictatorship syndrome through the ‘quest for sole power’ to ‘a lust for glory’ to ‘supreme isolation’

Well, this certainly applied to Mussolini – his invasion of Greece – and to Hitler – his invasion of the Soviet Union. And, I suppose, to Saddam who invaded one country too many. We were happy when he began his onslaught against our super-horrid enemy Iran in 1980, but we became very angry when he invaded our friend and ally Kuwait in 1990. But Nasser, as Aswany admits, suffered the ignominy of total defeat in the 1967 Middle East war. Arafat led the Palestinians from defeat to defeat until he shook hands with the Israeli prime minister on the White House lawn and signed up to a peace agreement that has been the curse of his people ever since.

Why, Aswany asks, again, did the Egyptians hold on to Nasser after Egypt’s colossal annihilation as a military power when the British dismissed Churchill after his victory in the Second World War? The author turns to the 16th-century French philosopher Etienne de La Boetie and his The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude. He advanced the logical idea that a dictatorship does not come about by the will of the tyrant alone, but “is a human relationship in which two parties are necessary: the tyrant who decides to subjugate a people and a people who have accepted such subjugation”.

Voluntary Servitude raises many questions, not least the horse which refuses to give in to its master until broken, after which it will happily prance around the ring and sidestep and curtsey at its owner’s will. Aswany talks about the moment “when a population waives certain freedoms and submits, by conquest or deception, to the will of one individual”, who becomes a dictator. There comes about a “long submission” to the will of a tyrant

The Egyptian novelist thus finds an explanation for Nasser’s popularity. “People who submit to a dictator,” he writes, “lose their yearning for liberty and behave in the manner of the sick who seem to be bewitched, hypnotised or unconscious. The Egyptians were struck down with the plague of submission to a dictator and they clung to him after he had brought about defeat, whereas the British [after the Second World War] enjoyed the sort of psychological wellbeing that made them elect a prime minister other than Churchill.”

It may also be, I suspect, that the British knew all too well about 20th-century dictators and merely decided that in their precious and still living democracy, they preferred a socialist who sought a new life for the poor and underprivileged than a hero who had little to offer a post-war people save memories of their victory.

I have to object here, by the way, to a rather sloppy grasp of historical facts. Aswany claims that on 8 May 1945, Churchill announced “the surrender of Germany and the end of the Second World War”. Untrue. The second world war in Europe, yes. But the war itself would continue in the Pacific until August of the same year. The July 1945 UK elections were not post-war, as Aswany says. But then again, many are the western historians of the Middle East who have forgotten their facts. (The most popular is the claim that Sir Arthur Balfour signed his Declaration in 1917, when in fact he only became “Sir” in 1922).

People who submit to a dictator lose their yearning for liberty and behave in the manner of the sick who seem to be bewitched, hypnotised or unconscious

But Aswany knows his tyrants. A dictator, he says, “sees his people in two contradictory ways ... he gives a central place to the people, always singing the praises of their genius and their astonishing ability to understand and read a given situation so correctly that they can distinguish between nationalists and traitors. However, on the practical level, a dictator has absolutely no faith in the ability of the people to think independently. This underestimation of the people is perfectly consistent with the concept of a paternalistic dictator. You love your children, but you would never trust their ability to manage things alone.”

This, however, slightly misses the point. True, Mubarak, in his last speech in 2011, spoke affectionately of the people as his “children”. But the children who really mattered to him were his biological children, especially Gamal Mubarak, who was being groomed as the next Egyptian dictator. Gaddafi’s son Saif was to achieve the same pre-eminence in Libya. The Gulf kings and princes practice hereditary rule to this day. Only one uncrowned head of state has actually passed on his power to his biological child: Hafez al-Assad, whose regime passed to his son Bassel.

Is this system of primogenitor – the essence of ancestry and family and obedience to the father and the worship of patriarchy – not also at the heart of dictatorship and tyranny, of secret policemen and torture and dungeons? We humans enjoy the feeling of security in the hands of our father-figures. I am reminded often of an old Iraqi friend who described to me his post-Saddam crisis: which matters most – freedom and anarchy, or fear and security? “Under Saddam,” he said, “I could travel on a bus and I knew what I could say to my fellow passenger – and what would get me into trouble. Now I can say nothing – because I don’t know which side my fellow passenger is on.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks