‘I remember his charisma could hold a room in his thrall’: My friend David Bowie

David Lister knew David Bowie. As we approach the fifth anniversary of his death, he recalls the early years of multimedia performances and his passion for art

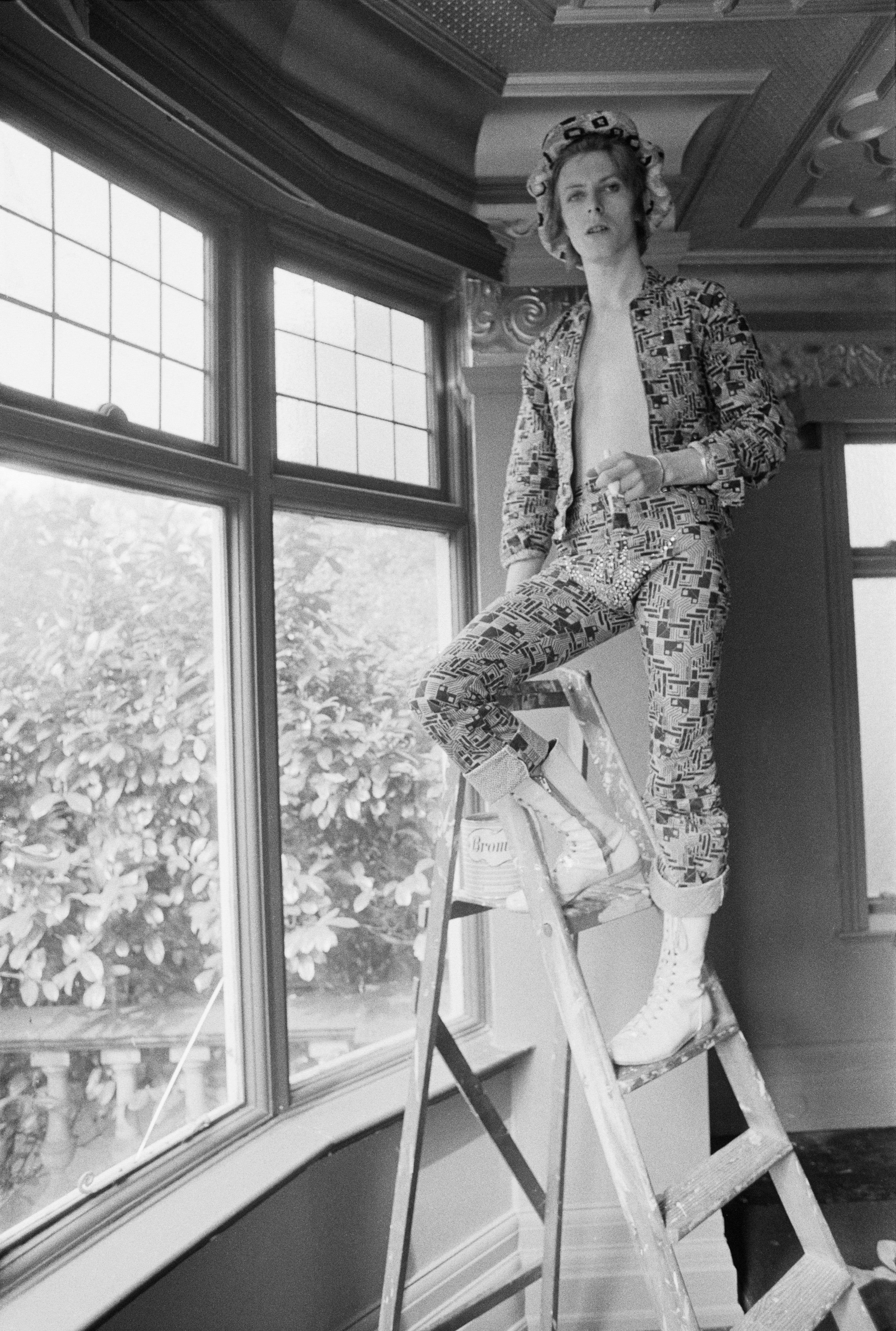

Like most right-thinking people of my generation – and subsequent generations – I was a huge fan of David Bowie. And when I was young, I was lucky enough to go to the now disappeared Rainbow theatre in London’s Finsbury Park to see him perform. That gig in August 1972 was to be one of the most memorable rock concerts of my life. For a start, the support band, a promising outfit called Roxy Music, weren’t half bad. The stage set, though, was odd. There was a ladder and scaffolding on stage, and I remember with some embarrassment remarking to my companion that it was pretty poor form by the venue not to have cleared all those remnants of renovation work away before the concert.

Well, rock as theatre was a new concept then, new that very night actually, especially with the multimedia elements it also contained –mime, dancers, a screen, a light show, you name it, so I’ll use that as an excuse. And then came the most theatrical sight of all. First, the sounds of Beethoven’s Ninth as adapted in electronic form for the then current film A Clockwork Orange. Then, Bowie came on stage – to gasps from the audience – in a blue Lurex jacket open to the navel, his hair described afterwards in a review by Petticoat magazine as “a solid bob of flaming Apricot Gold, made even brighter by a deathly white made-up face”. Bowie went through various costume changes during the show, again a novelty at a rock concert, and climbed to the top of the scaffolding for ‘Space Oddity’, to simulate being in space.

Ziggy Stardust had been presented to the world. Fellow anoraks might be interested to know that Bowie opened the concert with “Lady Stardust”, side two, track one of his recently released Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars album. Word of mouth and the reviews that followed that concert helped sales of the album to soar.

It was certainly a privilege to be at the Rainbow that night. But I’d never have dreamt, as I rubbed my eyes wondering if what I had seen was real, that I would become friends with the guy, receive Christmas cards from him and his wife Iman, and a limited edition recording as a gift from David, or that he would ask me to write the catalogue essay for his art exhibition, when he, perhaps a little nervously, made the foray from music to painting.

Fast forward more than 20 years from that magical Rainbow night to the mid-nineties. Bowie, his interest in art burgeoning, had taken a big interest, both editorial and financial, in the magazine Modern Painters. I was introduced to him by the magazine’s editor Karen Wright, who was a friend. Over a dinner with some others at Soho’s Gay Hussar restaurant we talked art, though I was secretly keener to talk music. I mentioned that I had just come back from an assignment at Blackpool’s rather splendid Tower ballroom. Had he ever been there? He gave me a look. “In the sixties and seventies, I played everywhere!”

I recall someone at the table slightly prissily remarking that one of the painters being discussed had rather loose morals sexually. “Oh, how unusual for an artist!” exclaimed Bowie, bursting into the loud and infectious roar of laughter that I was to get to know well.

Shortly afterwards he agreed to an interview with me for The Independent. It was at the time of one of his more experimental periods. He was telling me how his next album would contain mash-ups of found lyrics. Will there be any tunes, I asked a trifle impudently. “I doubt it,” he replied, accompanied by that idiosyncratic roar of laughter. We must have hit it off, and the discussion on art at the Gay Hussar had not been wasted, because he later got in contact to say he was putting on an exhibition of his paintings in London. Would I write the catalogue essay for the show?

I happily did. His figurative paintings were sometimes dark, always powerful, his self-portraits seemingly influenced by Francis Bacon, such was their ability to disturb the viewer.

His own art collection, on show at Sotheby’s a few years ago, which I reviewed, showed some of his other influences and his love of buying an extremely wide range of art. It contained works by, among many others, Egon Schiele, Stanley Spencer, Rubens, David Bomberg, Marcel Duchamp and Damien Hirst.

I was rewarded – and it was more than reward enough – with the gift of a two-disc CD and a Christmas card signed David & Iman, with one of his more abstract paintings on the front. He had written in pencil at the bottom that this card was number 66 of 150. I was more than happy to be number 66.

The album he had recorded, and which I now realise the 66/150 probably referred to, was signed for me with a personal message, and was called all saints. It was released privately, made as a Christmas gift for friends and family, and is a 90-minute compilation of largely instrumental works recorded between 1977 and 1993. He sent me my copy at Christmas 1994 after his art exhibition.

Indeed, I looked it up for the first time in writing this article, and Wikipedia describes it as “a two-disc set made as a Christmas gift for Bowie’s friends and family in 1993, only 150 copies of which were made. Due to its rarity, the album became a highly desirable collector’s item over the years.”

Believe it or not, I had not known that until this week. It was always one of my more treasured possessions. Now it is even more so. (By the way, all saints of 1993, made for friends and family, is not to be confused with All Saints of 2001, a commercially recorded album, with notable differences in track listing. Nothing is ever simple with Bowie).

We saw each other a number of times after that. I can recall sitting next to him for part of one of the Q magazine award luncheons. He was to receive an award jointly with Brian Eno, his producer and collaborator during his Berlin years in the seventies. Back at the Rainbow, of course, Eno had been part of that first Roxy Music line-up.

At that Q awards lunch, David would occasionally turn to Iman to make a remark about one of his peers collecting an award. I would have loved to have known what he whispered to her about Van Morrison. Whatever it was, it achieved the feat of bringing a half-smile to her sphinx-like face, normally set in the same, eminently photographable expression. (My own efforts to start a conversation with her were rather one-sided. Superstars are much easier to engage with than supermodels, I found).

There was a gathering of the award winners on stage for a photo taking place at the conclusion of the lunch, and a couple had already gone up. I nudged Bowie. “Go on, up you go.” He glanced at the stage. “I don’t know. It’s a bit sparse.” A lesson for me there. A true superstar likes to make his entrance towards the end, not the beginning.

I’m glad we had bonded during that decade, because it made the next meeting one that we could laugh about, rather than making him angry. It was a strange and memorable occasion, leading certainly to the biggest scoop I ever had in my journalistic career, and one that travelled round the world.

It occurred on a sultry evening in New York in 1998. There was a reception hosted by Bowie at the artist Jeff Koons’ studio on the corner of Broadway and East Houston Street. It was for the launch of William Boyd’s book Nat Tate, a history of the American abstract expressionist who suffered from depression and destroyed 99 per cent of his work. His short, tragic life ended when he committed suicide at the age of 31 by jumping off the Staten Island ferry.

Bowie read from the book at the reception while the great and the good, the cool and the goggle-eyed of New York’s art world, all listened intently, keen to learn more of the exploits, art and genius of Nat Tate, though some, of course, muttered about how they had long appreciated him. And this all was taking place in the surreal surrounds of Jeff Koons’ kitsch sculptures, stainless steel balloon dogs and rabbits.

It was a major event with British national papers running extracts from the book and reporting on the launch. Among the guests at the stellar launch were artists Frank Stella and Julian Schnabel, novelist Jay McInerney, Paul Auster and Siri Hustvedt.

But I had discovered the rather wonderful truth, namely that Boyd’s book was a stunningly brilliant hoax by an excellent author, a satire on that very art world. Nat Tate had never existed. I sought out some of the addresses cited in the book, and they didn’t exist either. Bowie at that time only drank water and sent an assistant to get some as he embarked on reading from the page about Tate’s death to the assembled gathering. I caught his eye. He was certainly in on the hoax. Whether he guessed what I was about to reveal, I have no idea, but I did get one of those inimitable, impish grins. I do believe he saw the funny side; William Boyd less so, as my subsequent front-page exclusive in The Independent, somewhat lessened the effect of the upcoming London launch of the same book.

The book, Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960, was the first to be released under the imprint of Bowie’s new publishing venture, called 21. The elaborate hoax (exposing amid much else the art world’s fear of ever saying the dreaded words “I’ve never heard of him”) was a project that would undoubtedly have appealed to his love of fantasy, acting a role, creating a persona, and being mischievous.

Indeed his sense of mischief almost went too far. He wrote on the cover of the book: “William Boyd’s description of Tate’s working procedure is so vivid that it convinces me that the small oil I picked up on Prince Street, New York, in the late Sixties, must indeed be one of the lost Third Panel Triptychs. The great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist’s most profound dread – that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist – did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate.”

The Nat Tate saga ran and ran. In 2011, Sotheby’s sold a drawing by Nat Tate. It was, of course, by William Boyd. And when, relatively recently, I looked up Nat Tate on Wikipedia, I found that my part in his unmasking was duly recorded, but so was the conclusion by Newsweek magazine that I too did not, and do not, exist.

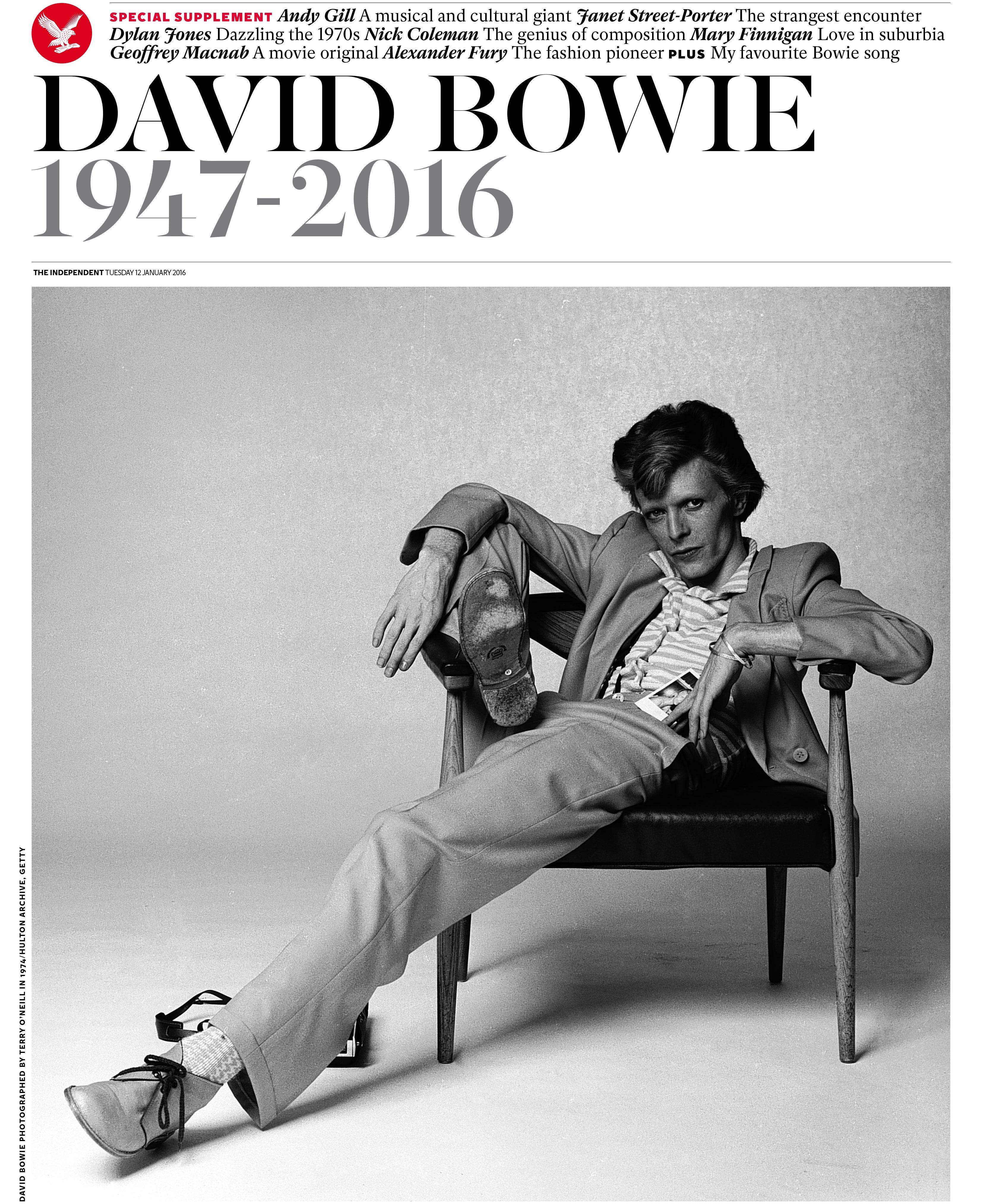

All those happy and varied memories of Bowie contrast, of course, with the sadness and shock that I and all his fans across the world felt on the morning of 10 January 2016. The Independent’s print edition still had a few months to run, so we were able to produce a special supplement commemorating David Bowie’s life, which I helped to organise, as well as writing a piece about my memories of him.

How do I most remember him now? I remember his eagerness and curiosity to chat about art across all the art forms. I remember that he was endearingly tactile. Most of all I remember the indefinable -- his charisma that could hold a room in his thrall. A sort of stage presence, which unusually even among those who possess it, was evident off-stage too. I remember his generosity. I remember that heartwarming smile, which could in a startling second become a roar of laughter, and set the whole room laughing too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks