The complicated story of Damon Smith, a bomb and autism

In 2017, Damon Smith was sentenced to 15 years in prison for planting a bomb on a London Tube train. But without a lawyer or jury that understood his Asperger’s, was it a fair trial? Katie Glass reports

At 10.30am on 20 October 2016, 19-year-old Damon Smith boarded a Jubilee line train at Surrey Quays station with a bomb ticking in his black Adidas rucksack. It was timed to explode at 11.02am. At 10.49am, CCTV captured Smith leaving the Underground. There was no sign of the bag.

It was at almost 11am, as the train approached Canary Wharf station, that two passengers spotted it. They alerted the driver who, seeing wires protruding from it, called the authorities for help. As the train and platform were urgently evacuated, scattering fearful commuters into the street, North Greenwich station was cordoned off and explosive experts dispatched to the scene.

Seven months later, Smith stood in the dock at the Old Bailey accused of planting a bomb on the London Underground. It was the week of the Manchester Arena attack. In those awful days, after an Islamist suicide bomber senselessly slaughtered 22 children and adults at a teenage pop gig, it felt like the whole country was in grief. Smith grinned through his trial. He’d constructed his bomb from a £2 Tesco alarm clock and flask. If it had detonated, the Met’s head of counter-terrorism, Dean Haydon, said, it would have “caused mass casualties”.

Smith was arrested on Holloway Road by police who tasered him twice. In mugshots he has blood on his forehead. Counter-terrorist police raiding the Rotherhithe home Smith shared with his mum found “a personal militia” of weapons: a knife, a blank-firing, self-loading pistol, a knuckleduster and a BB gun.

At his trial, jurors heard how Smith was obsessed with weapons. YouTube clips showed him posing with weapons. In one he aims a pistol. “Hello everyone,” he says. “I am going to shoot my gun”.

Smith was arrested carrying a copy of the Quran. Jurors heard how police found photographs on his computers of Islamist extremists. As he was sentenced to 15 years with five years on licence, Judge Richard Marks QC spoke about “the background of fear in which we all live … an all too timely reminder of which were the events in Manchester earlier this week”.

Yet Smith’s case struck me as different. When is a terrorist not a terrorist? When is a bomb not a bomb?

You can watch Smith’s police interview on YouTube. See how he sits, hands on his lap, in the interview suite, his hair messy curls, a patchy goatee, a grin on his baby face. He speaks with a high-pitched girlish voice almost laughing as he describes how he left the Underground at London Bridge on his way to London Metropolitan University and “realised I had like two hours to kill … before my next maths lesson”.

It is during this interview Smith first claimed his device was intended as a Halloween trick. In court this will be his defence. It is still what he claims in letters written to me from prison. “What I done on the train was a prank,” he writes.

Smith lived with his mum, Antonitza, in a red brick two-up two-down on a south London estate; surrounded by high rises that teenage boys patrol on bikes. The trainline runs past the back of their house.

It was here Antonitza stood looking out of the kitchen window thinking she fancied some chips, when 14 plain-clothes counter-terrorist police officers arrived to raid her house, telling her that her son was being charged under the Terrorism Act.

Antonitza pads around making tea. She has been on antidepressants since Damon’s arrest. As she speaks she collects things: her son’s certificate of excellence from college, his school reports. She wants me to understand him in a way she feels the jury never did.

He just liked BB guns because we lived in Devon. He’d play on a target in the garden or go to the moor … it was so innocent

She raised Damon in the rural Devonshire village of Bovey Tracey, on the edge of Dartmoor, with no contact from his dad. “He wasn’t like a normal child,” Antonitza says. As a toddler he flapped his arms. He’d spin. By three, he still couldn’t speak. When he started nursery, because he didn’t talk, they asked if he was deaf. The teacher said Damon “just sits under the table making noises”.

He developed fixations. “When Damon gets into something, he gets into something,” as Antonitza puts it. As a toddler it was Thomas the Tank Engine, then fire engines. “When he was very tiny he liked hoovers,” Antonitza laughs. “He had a Henry hoover. A Dyson”. Later, it was films. “He could recite the whole of Star Wars,” Antonitza grins. When Damon discovered YouTube he’d endlessly re-watch clips. He started his own channel, uploading videos. “Likes and views were important to him,” Antonitza says, “probably because he had no friends.”

When Damon was eight he was diagnosed with high-functioning Asperger syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) characterised by repetitive behaviour and difficulty interacting. He was “shy” and “well-mannered” but because of his learning difficulties he struggled to socialise. He was bullied, often violently. When Damon was nine Antonitza bought him a dog, Scooby. “The dog was his only friend.” From 10-13, Damon moved between special schools. “He didn’t have a normal life really,” Antonitza says to me. She starts to cry: “Now he never will.”

In letters from prison, Smith writes simplistically about what had been his “everyday normal life. I go to uni, go casino, listen to music, take the dog out, go places, always with mum.” The casino was another fixation. A teacher taught Damon poker when he was 12. As a teenager he continuously watched videos of Daniel Negreanu – one of his favourite poker players, whose books he would read again and again. At 18, Antonitza would drive him to Torquay casino every Wednesday to play poker “to help him socialise”. In London, Smith joined Aspers and the Hippodrome Casino, taking pictures of himself with fistfuls of £20 notes. He wins, says Antonitza, because “he hasn’t got any fear … he’s not scared of going all in”.

Although Smith had the academic capability to secure a place at London Metropolitan University reading forensic science, socially he was still “like a child”, Antonitza says. When he moved to London she came with him. “He wouldn’t have been able to look after himself. He couldn’t cook. He’d get lost. He’s never been to a pub or a nightclub like other kids his age.”

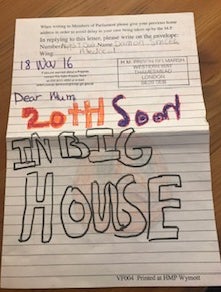

Antonitza showed me a letter from Smith – then a category A prisoner at Belmarsh. It is shocking in its childishness. Written on prison paper in purple and orange felt tips, he’s drawn a big picture of a sad orange face. “Still a big shock that I’m in prison,” he writes. “Missing YouTube”.

“He didn’t realise the seriousness of what he’d done. He didn’t realise the consequence” Antonitza says, “In his eyes it was just a prank.”.

Pranks were one of Damon’s fixations, Antoniza explained, telling me how he’d once hacked the school computer, changing the marks of a boy who’d bullied him. For other ‘tricks’ Damon has registered his granddad on a dating website, as a joke. Once, he bought insects from a pet shop and let them off in McDonalds.

Smith loved to watch prank videos on Trollstation and YouTube; among his favourites were “public bomb scare” pranks. In some, young men in Arabic dress leave rucksacks in malls, or parks and watch the results as people run scared. Some have over 12 million views.

I sat several times with Antonitza and her mother in that Rotherhithe kitchen. I asked if they believed Smith had intended his “bomb” as a prank? “Yes,” they said. “100 per cent,” said Antonitza. “Because we know him,” added her mum.

Every question I ask about Damon’s case, Antonitza answers. The guns found in her son’s room were BB guns, Antonitza points out. “He just liked BB guns because we lived in Devon. He’d play on a target in the garden or go to the moor … it was so innocent.” The knife was a fishing knife she’d bought him that Damon would “take down Hope’s Nose and gut the fish on the rocks”. Damon bought the knuckleduster for £5 on holiday in Turkey. Antonitza guiltily admits she encouraged his interest in martial arts, taking him to Taekwondo “to give him confidence”.

She’d seen Smith’s YouTube video of him firing his BB gun. “He did it to get views and likes,” she says. “He also uploaded videos of poker and computer software.”

Police dispatched to their previous home in Newton Abbot evacuated the street after finding a suspicious package in the attic: a clear plastic jar with protruding wires, containing ball bearings and metal bolts. However, bomb scene examiners concluded that although it looked like a bomb, it was not viable. Antonitza knew about it. “When we lived in Devon you don’t really think about coming to London – it’s so serious,” she shrugged.

Although our present court system allows a jury to hear the diagnosis of autism, it doesn’t allow a jury to hear how autism may have contributed specifically to what the defendant is being charged with

In court, Smith’s barrister described his act on the Underground as a progression of his previous “play-acting” rather than “a massive sudden leap into the deep end”. “Apparently,” says Antonitza casually as she brings me a fresh cup of tea, “he made it [his device] upstairs.”

At his London home police recovered an iPad containing a photograph of Smith posing with an image of Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the Islamist terrorist behind the November 2015 Paris attacks. They found he’d visited al-Qaeda sites, printing out articles including one entitled “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom”. They found a list of bomb-making materials, which included the text: “Keep this a secret between me and Allah #Inspirethebelievers”. When I ask Antonitza and her mother about the Quran Smith was arresyed with, his gran says sheepishly: “I bought him that. I also bought him Of Mice and Men.” She got them for Smith’s GCSEs. He’d got an A star in religious studies and – as was his tendency – became very interested in Islam. He could recite passages from the Quran by heart. “That’s his brain,” Antonitza says.

I ask about the photograph of Smith with Abaaoud. “It was his birthday. I was taking photographs as he was opening his presents,” his gran explains. As she snapped away, Abaaoud appeared on the television behind Smith in a news report. On her iPad she shows me the image of Smith with Abaaoud on the TV behind him. She flicks to the next photograph, and Abaaoud is gone.

It was true that he’d visited extremist sites, Smith wrote to me. “You’re not going to get a bomb manual from a peaceful Buddhist website. If you interested in bombs you have to look at extremist manuals,” he explained in his oddly practical way. It was while cut and pasting such instructions Smith inadvertently pasted the “#InspiretheBelievers” message.

Smith admits he looked at pictures of Osama bin Laden and watched videos of Saddam Hussein and Anjem Choudary. He watched Trollstation and gambling videos too. “I spend all day on YouTube,” he says, “It’s not illegal to be interested in things.” Damon explains that there were pictures of Islamist fighters on his computer because he’d made his own fake Isis YouTube video – another “joke”.

In the end all terrorism charges against Smith were dropped. He was tried for possessing an explosive device with intent. As his solicitor wrote to Antonitza: “The issue for the jury is in many ways very simple: did he or did he not have the intention to endanger life? If he did he is guilty and if not innocent”.

In court, explosive expert Lorna Philp said that – in her opinion – Smith’s bomb was “an improvised explosive device designed to explode and produce fragmentation that could cause injuries to persons and damage to property within close proximity”.

By contrast, Smith has always maintained he intended to make a harmless smoke-spewing bomb, insisting he’d deliberately modified his device from the instructions he’d found online to make it less harmful. His barrister told the court: “If you’re looking for a bang, you don’t choose something that makes a fizz.” Or as Smith dispassionately wrote to me: “If I’d wanted to kill people I’m not going to use a thermos flask. I’d use pressure a cooker.”

One time, I was sitting in Antonitza’s kitchen when Smith called from Long Lartin prison. Despite his letters and everything Antonitza had told me, I was still surprised how he sounded on the phone. His voice was high-pitched and childish, just as it had been in the police interview. His manner was oddly matter-of-fact. He described how he’d used a flimsy flask, not a solid pipe; sparklers, not fireworks and non-flammable PVC glue to make his device. When I pointed out how awful the results of his bomb could have been – according to experts – he agreed: “It would have been pretty bad.” But he told me: “I don’t think of it as being dangerous. I didn’t want to hurt anyone”.

At times, I sympathised with Smith and Antonitza. At times, I found their claims far-fetched. In particular I was troubled by one aspect of the case. The prosecution noted Smith had affixed “ball bearings” to his device, which they claimed were shrapnel intended to harm. Smith said he’d “chucked in” the ball bearings so that when police saw the device he’d created they’d be convinced it was real – not think it was “like a kiddie smoke bomb”.

Smith told me he wanted to make something newsworthy to “shut down London” and “shut down the trains”. “I wanted to watch it on the news,” he said. After leaving the rucksack on the train, he repeatedly checked the internet to see if his explosion had made the headlines. TV was important to Smith. He wrote to me describing how he’d been driven to court in a bullet-proof truck “seen on the BBC”. “Nee-naw,” he wrote.

I thought of Smith’s jury on the Tube to court hearing the announcements urging commuters to report “suspicious packages”; hearing his case days after the Manchester attack. “This is a difficult climate to ask for mercy for someone convicted of this type of offence,” Smith’s barrister said,

“Nevertheless, this case is different. It seems unique and so is this young man.” But can the square judicial process accommodate a round peg like Smith?

It took the jury just two hours to find Smith guilty. Sentencing him, Judge Marks said: “Quite what your motives were and what your true thinking was in acting as you did is difficult to discern with any degree of clarity or certainty.”

I struggled to understand Smith’s intent. I also wondered if the police, jury and judge has been given a good enough understanding of his condition. Indeed, had Smith understood the legal system in which he found himself well enough to meaningfully contribute to his defence?

This year Doctor Clare Allely, a reader in forensic psychology, co-founded a centre at the University of Salford studying autism and the criminal justice system. “If someone presents with autism it should definitely be a consideration in the criminal justice process,” Allely says, expressing concern that there may “be cases of individuals with ASD serving sentences for engaging in terroristic behaviours despite having no intention to carry out harm to others”.

Allely explains that people with ASD are “less likely to think about and appreciate the consequences of their actions and how society would view them”. She gives the example of a nine-year-old autistic boy, Jake Edwards, charged with making terroristic threats in the US, after writing “bone thrat” (bomb threat) on his school’s bathroom wall. He’d seen a similar event cause a school to be evacuated and hoped copying it would get him and his classmates out of school to “have fun”.

There is a saying: “once you have met one person with autism – you have met one person with autism”. Autism manifests in different behaviours. Allely notes: “Although our present court system allows a jury to hear the diagnosis of autism, it doesn’t allow a jury to hear how autism may have contributed specifically to what the defendant is being charged with.”

Antonitza provided Smith’s lawyer with her son’s school reports and past medical records but they were not presented in court. She wanted his Child and Adolescent Mental Health psychologist, who’d known Smith since he was nine, to give evidence – but tells me his lawyer advised against it. A new psychiatrist was enlisted. His report, read in court, spoke about Smith’s interest in bomb-making: “He didn't think it was an issue – he thought it was just an interest,” he wrote. Does an interest alone prove dangerous intent?

Allely notes autistic obsessions do not necessarily lead to actions: “A fixation does not directly signify a risk.” Individuals may “develop an interest in say, bomb-making, but that doesn’t mean they will act on it”. She adds: “There are some cases that once the autistic person is told something they are doing is wrong – and the implications of it such as the harm to others are made clear – they will stop engaging in that wrongful behaviour.” I asked Smith when we spoke if he would make another bomb. “No,” he said, shocked. “I’d go back to jail.”

On the first day of his trial, the judge asked the jury to disregard Smith’s grin. “It’s one of his traits of Asperger’s,” Antonitza explains. “He can’t help it. The jury should have had more understanding about Asperger’s.” Allely says that people with autism often exhibit behaviours such as avoiding eye contact, appearing to lack empathy, displaying inappropriate facial expressions, shifting the topic of the court discussions to a topic they have an interest in – all of which can make them appear untrustworthy or remorseless to a jury.

Smith wanted to give evidence. His solicitor advised against it. Yet Allely’s says “many people with autism are capable of providing high quality evidence if adaptations are made to meet their needs”. In cases featuring vulnerable defendants, modified procedures can be introduced. Judges may dispense with wigs to make court less intimidating, allow evidence to be given via recorded video or intermediaries to be used to provide special support, allowing defendants the opportunity to understand and effectively participate in their trial. Smith claims he was offered no such special measures. “I wish I’d given evidence,” he says. Did his legal team even request the judge to advise the jury that Smith’s condition affected his ability to take the stand? When I asked him Smith’s solicitor, he declined to comment.

Antonitza tells me Smith suffers from anxiety. He cried as his trial began. She says she’d informed his legal team, who did nothing. “Damon needed a solicitor who knew about Asperger’s,” she says.

Some campaigners believe prison is an inappropriate environment for autistic people and where possible courts should consider alternatives. Laura Janes, legal director of the Howard League for Penal Reform, says autistic prisoners often severely struggle to adapt to the prison environment. Some find it so disturbing they prolifically self-harm. Some, misunderstanding prison rules, are penalised, adding time to their sentences. Janes suggests one alternative is hospital, adding: “With the right support individuals can develop skills, capacity and insight to better manage their autism.”

Sue Hemming, head of the CPS’ Special Crime and Counter Terrorism Division, described Smith’s actions as “incredibly dangerous … The consequences had the device worked do not bear thinking about”.

“I don’t think Damon’s innocent,” Antonitza says. “I just think he should have got a fair trial – he should have had a jury who understood Asperger’s. He should have got eight to 10 years.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks