The true story of the Cottingley Fairies hoax

A century ago the world was enthralled by the photographs of the Cottingley Fairies, one of the greatest hoaxes of all time. But, asks David Barnett, what if it was all true?

When she was 16 years old, Christine Lynch was sitting with her brother David in their family home in Nottinghamshire, talking about, of all things, the possible existence of parallel worlds.

This would have been just after the Second World War. Her mother and father were also in the room, reading newspapers or listening to the wireless, while Christine and David talked.

Both youngsters were big fans of science fiction, and devoured the pulp magazines that were hugely popular in the 1940s, filled with tales of other worlds, other beings, and big ideas.

The story they were discussing was about another Earth closely aligned to ours, and a dog that had passed between the worlds (Christine can't remember the author or the title but it could, possibly, have been Olaf Stapledon's Sirius, or an extract from it, which was published in 1944).

The children’s mother was listening to their conversation, and she asked them to go and get a book from her bedroom. It had been written more than 20 years previously by Arthur Conan Doyle, and while this was no Sherlock Holmes thriller, it was certainly a story with, at its heart, a mystery that might have confounded the great detective as much as it did his creator.

Read More:

The book was called The Coming of the Fairies, and was Conan Doyle’s treatise on one of the most enduring stories – and accepted hoaxes – of the past century.

Christine and David’s mother had been listening with interest to the talk of parallel worlds, and thought it was time the children knew a little about something she had been carrying with her for almost three decades, and very rarely spoke about.

Conan Doyle’s book was about the Cottingley Fairies, the celebrated case in which two young girls, Elsie Wright and her cousin Frances Griffiths, took photographs behind Elsie’s home in the West Yorkshire village near Bradford of tiny winged sprites among the trees and burbling waters of Cottingley Beck.

Christine’s mother was Frances Griffiths, one of the girls at the heart of a story that became known the world over, and finally she decided it was time her children knew the truth.

The story is a well-worn one, but bears repeating. It was the summer of 1917, Elsie was 15 and lived with her parents Arthur and Polly and, for the duration of the war, her cousin Frances, nine, and her mother, Polly’s sister, Annie.

She’d never talked about it before, she never talked about it to anyone. She said it ruined her life, actually, all the publicity. The story followed her through her childhood until she married. She was always terrified about it coming out

Frances had spent all of her early life in South Africa until arriving in England in 1917, and despite the age difference between the cousins, the two girls spent a lot of time together, exploring the wooded area behind the house on Main Street in the village.

Four years ago, to mark the centenary of the Cottingley Fairies incident, I visited the house on Main Street, and the current owner showed me down the sloping garden to the secluded, shadowy stream that ran behind. A couple of hops across large rocks took you to a little dell, and above it a large field – now developed, but a century ago a secret little paradise.

Just the sort of place to see fairies. At least, that’s what the Frances said when she kept getting into trouble for getting her shoes and stockings wet in the stream. She was only going there to see the fairies, she said.

When the girls asked him to borrow his camera to prove there were fairies, Arthur Wright entrusted his daughter and niece with his Midg quarter-plate camera – Elsie was working full-time in a local photographic studio but had never taken pictures herself – and told them to return with evidence.

Half an hour later they presented him with the camera, and Arthur developed the plate in his amateur darkroom at home. What emerged was going to make history.

It showed the head and shoulders of a solemn Frances with the image of four fairy figures dancing in front of her on the bank of the Beck. It was a good joke, thought Arthur, a nice riposte to his demand for evidence. Cardboard cut-outs and nothing more.

A while later the girls borrowed the camera again and returned with a photograph this time of Elsie, holding out her hand to what appeared to be a foot-tall elf or sprite. The joke had worn thin for Arthur by now, and worried that the girls might damage his precious camera, he told them not to take it again.

And there the story might have ended, except two years later, in 1919, Polly Wright attended a meeting of the Theosophical Society in Bradford, at which the topic of discussion was fairies. Polly had taken along the two photographs to show at the meeting, and they caused a minor storm. So impressed were the organisers of the Theosophical Society that they asked to display the photographs at their annual conference in Harrogate some months later, and there they came to the attention of Edward Gardner, a leading and influential member of the organisation.

Gardner sent off the photographs to be looked at by various experts, who declared that they had not been tampered with in any way, that the images were not faked, and that whatever was in front of the lens was undoubtedly real.

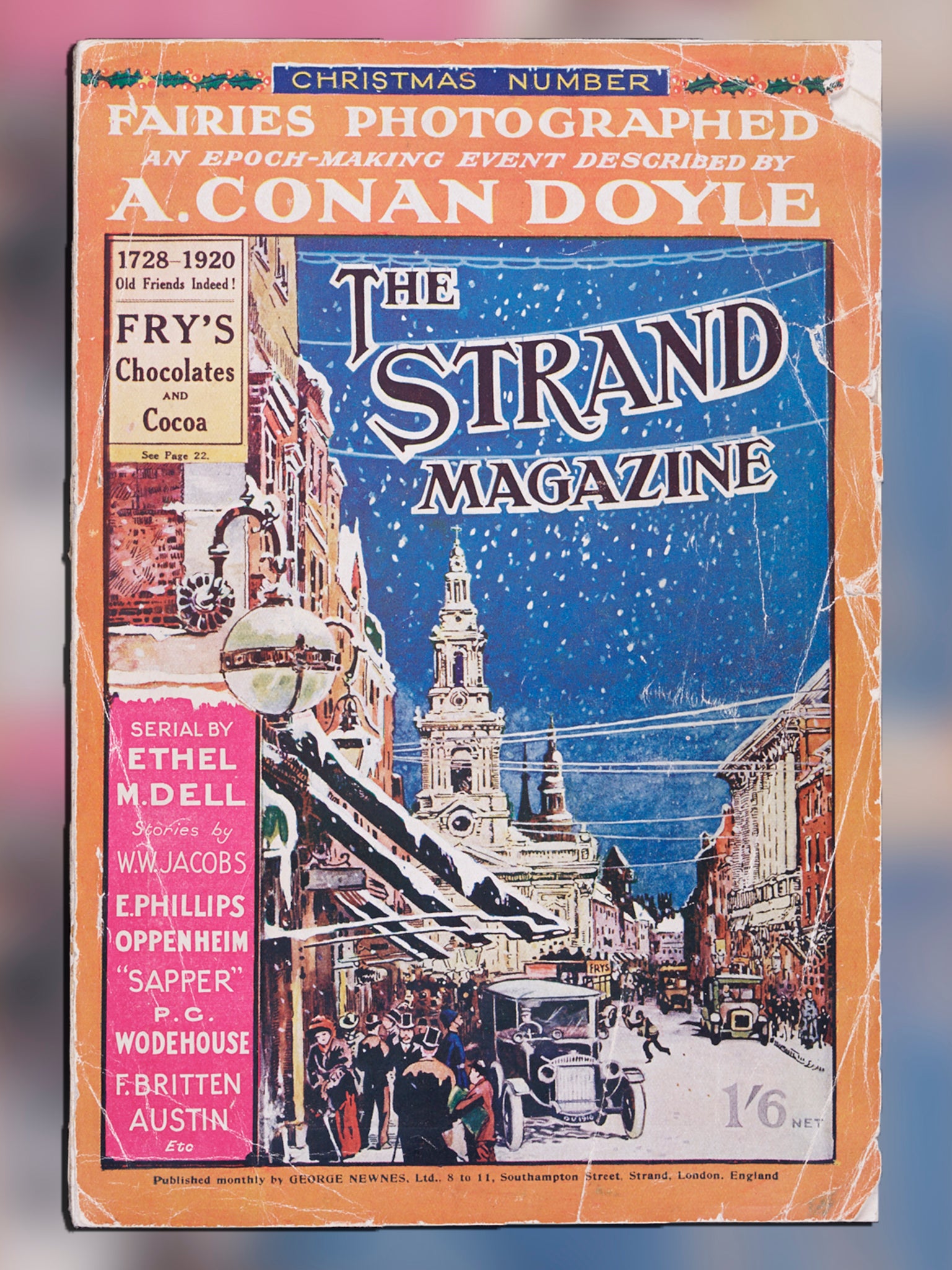

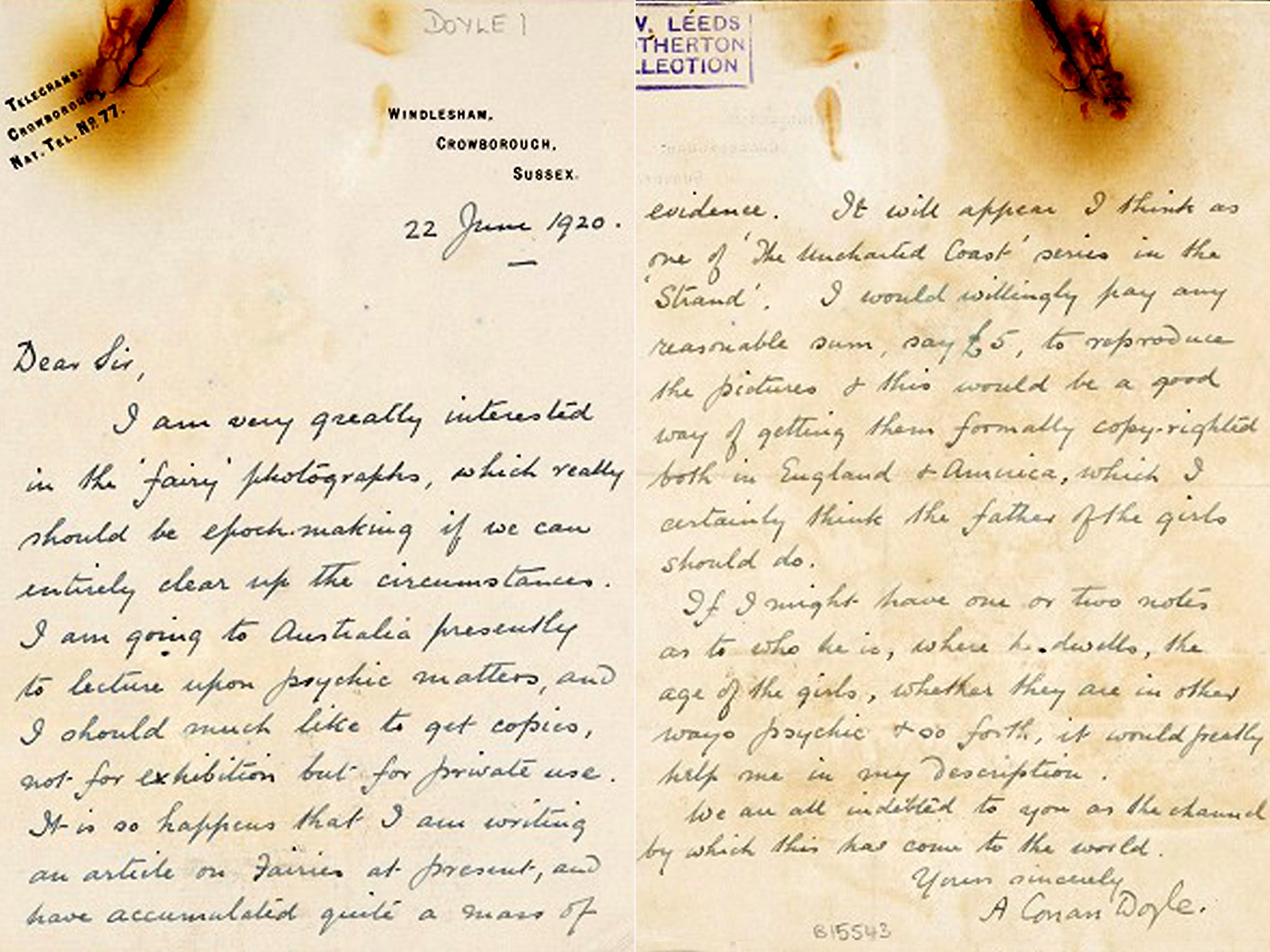

It was in 1920 that the photographs came to the attention of Arthur Conan Doyle. He had been commissioned to write a feature on fairies for TheStrand Magazine, berth of his Holmes stories, and the growing attention on the Cottingley photographs was a perfect hook for him.

Conan Doyle wrote to Arthur and Polly Wright and asked for permission to reproduce the photographs, as well as seeking more clarification on their veracity from experts at Kodak. The technicians couldn’t find any evidence that they had been faked, but the company couldn’t issue a formal verification because of the subject matter. The pictures might have been perfect, but surely fairies could not exist?

She was in a dilemma. They knew the other pictures had been faked, so how could she say that this one was real and the others weren’t? It was a terrible situation, so she just preferred to keep quiet about the whole thing

Conan Doyle put into the mouth of Sherlock Holmes the immortal phrase: “Once you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.”

It was, he thought, impossible that the photographs were faked. Therefore, logic dictated, the fairies must be real. He despatched Gardner with two W Butcher and Sons Cameo folding plate cameras to give to the girls and ask them to take more photographs.

Both of those cameras, as well as Arthur’s Midg, are in the collection of the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford. In 2017 I was taken into the bowels of the museum and shown them, and got to hold one of the cameras Conan Doyle had sent up to Elsie. Here was a piece of proper history, handled by Arthur Conan Doyle, and used by two girls to create one of the biggest hoaxes in the world.

Because, of course, the Cottingley Fairies were a hoax. Despite the fact that Conan Doyle himself was so convinced, despite the fact that when his article was published in The Strand in December 1920 the magazine sold out instantly. Despite the fact that a world still recovering from a devastating world war and a virulent Spanish Flu was desperate to believe in something to blunt the impact of those twin horrors.

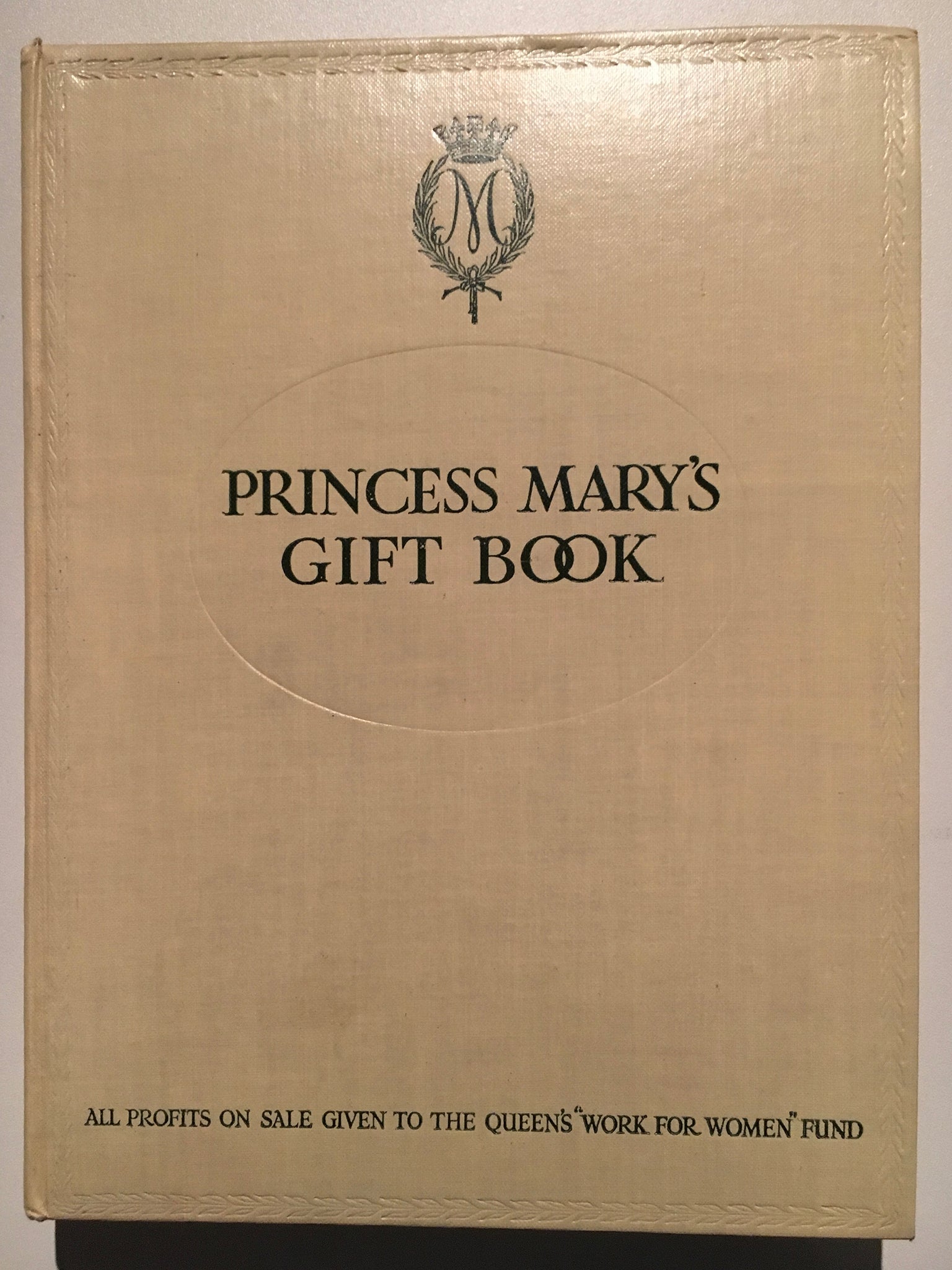

In 1983, in an interview given to the paranormal magazine The Unexplained, Elsie and Frances admitted that the pictures were faked. Elsie had copied illustrations of fairies from a 1914 edition of Princess Mary’s Gift Book and stuck them to the ground and bushes with hatpins. It was all just a bit of fun that got a little out of control. When people started believing the story, the girls felt too embarrassed to admit the truth, for fear of making no less than Arthur Conan Doyle feel ashamed for being taken in.

Which was why it took for Christine Lynch to get to the age of 16 before her mother Frances Griffiths sat down and spoke about her part in the whole Cottingley Fairies affair.

“She’d never talked about it before, she never talked about it to anyone,” says Christine. “She said it ruined her life, actually, all the publicity. The story followed her through her childhood until she married. She was always terrified about it coming out.”

The Cottingley Fairy photographs in the December 1920 edition of The Strand Magazine caused a sensation, and later Conan Doyle’s book The Coming of the Fairies was published (though with the names changed and Elsie and Frances recast as Alice and Iris), Edward Gardner released his own book, Fairies, as well. Christine says: “She went into the local library in the 1940s and this book had just been published and there it was on the table. She was so horrified that she just turned around and got on her bicycle and went home, and said the family had to move house immediately.”

Frances’ husband Sid was a regular soldier in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and in 1933 he with his family was posted to Heliopolis, Cairo, Egypt, which is one of Christine’s earliest memories – they were there until 1937, when Christine was five; she vividly remembers sitting on a train at the Alexandria docks looking up at the huge liner that was to take them back to England. She also remembers a visit to the pyramids in a huge sandstorm, and seeing the Sphinx covered with sand right up to its head.

The family lived in Richmond, North Yorkshire, for a while and then moved to Nottingham. During the war years Christine can remember lying in bed listening to the thoom-thoom-thoom of the jet engines being tested at the Rolls Royce plant 18 miles away, and German planes flying overhead on their way to bomb Liverpool, Coventry and Birmingham. The streets of Nottingham were full of British and American army and air force servicemen and women.

When Edward Gardner released his book Fairies in 1947, Christine says: “My mother went into the local library and to her dismay she saw at the entrance a table piled with copies of the book with her photograph on the cover. She was so upset and horrified at the thought of being found that she got on her bicycle and went home.”

“She just didn’t want to be associated with the story at all,” says Christine, who is 90 and now lives in Belfast. “And that’s purely because the pictures were faked and so many people believed in them. They didn’t want to let anyone down or make anyone feel bad and Frances hated being associated with something that was fake.”

It’s really unfair to label the Cottingley affair a “hoax”, because that implies an intent to deceive. It’s evident that Frances and Elsie got caught up in something they never intended.

Except there is a rather big “but” here. The first two pictures were indeed fake. Three more were taken with the cameras that Conan Doyle sent in 1920. Two of them were also set up using cut-out fairies, because the girls didn’t want to disappoint the great writer and all the people waiting with bated breath to see more fairies.

But the fifth picture, Frances Griffiths maintained until she died in 1986 was absolutely genuine. There really were fairies in Cottingley. Frances had seen them. And, says Christine, the fifth picture is the proof.

By 1920, Frances was living in Scarborough, and had come back over to the Wright house after Conan Doyle sent the cameras to stay a while and take more pictures with Elsie.

The fifth and final picture of the Cottingley Fairies set is different to the others. It doesn’t feature either of the girls posing with fairies. It’s more ethereal than the others, less staged. It is a sharp close-up of wild meadow flowers, and in the foreground are a clutch of haunting, almost translucent figures, that don’t look quite as though they are fully formed.

“My mother was brought back from Scarborough and they were told to go out and get more photographs,” says Christine. “Elsie had two faked already. It had been raining all the week before, and this was the first chance they’d had to get out. Polly said to them, ‘it’s brightening up, you’d better go out and try again, these men have spent a lot of money on these cameras’.

“So they went out and mooched around the place, but instead of staying around the Beck they went up the path to the field and didn’t really know what to do. They put their coats down on the wet grass and sat there talking for a while until it was time to go home.

“Frances had the camera on her knee and the grass was uncut so it was quite tall and she saw about three feet away from her what looked like a nest, an oval of grass. And that’s what she saw, she didn’t see any fairies, she just saw an oval of grass. And she thought it was a bird’s nest so she set the focus and distance and took the photograph.”

The next day Frances went home to Scarborough and it was only when her Uncle Arthur developed the negative the next day that the picture emerged. The photograph that Frances had always maintained was absolutely genuine.

When Arthur sent a copy to Frances she realised that finally she’d taken a photograph of real fairies, says Christine. So why did the girls both admit to faking the pictures if they genuinely believed this was real?

“She was in a dilemma,” says Christine. “They knew the other pictures had been faked, so how could she say that this one was real and the others weren’t? It was a terrible situation, so she just preferred to keep quiet about the whole thing.”

Until her daughter and son were talking that day about parallel worlds, and the dog that crossed between them, which was when Frances broke her silence to her children. Because, thinks Christine, that is perhaps the most likely explanation for what Frances saw.

Christine Lynch is a forthright, grounded woman who set up a cancer charity with her husband – at the time of his death in 1988 he was the director of cancer services at the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre in Belfast. Talking to her, she comes across as someone who is vitally keen that facts are correct and properly presented. And yet she utterly believes that there were fairies at the bottom of that Cottingley garden.

“I think it’s obvious that my mother was psychic,” says Christine, matter-of-factly. “My daughter is slightly psychic, my grandmother was slightly psychic. I think there is something in the brains of people like this that opens up doors between worlds, that makes it possible for things to come through and be seen. That’s my theory, anyway.

“There must be something special in some people, the way they see things that other people don’t, and how it happens totally out of the blue. Frances saw the fairies on an ongoing basis and that’s very rare. Before all the photographs started, she was seeing them. She was an only child, her father was at war in France, she spent a lot of time on her own by the Beck and because her mind was totally clear and she was often alone she saw them.”

Christine doesn’t claim any psychic abilities of her own, but she does have utter faith in her mother and the assertion that the final photograph really does show what it purports to. And she’d like science to back her up.

Read More:

She says: “If that photograph looked like the others, the ones that were fakes, then I wouldn’t believe it. But it’s so different. And knowing my mother, knowing how honest she was and how stressed she was at the charade they’d been forced into I totally believe her.

“What I would like now is for someone to do a really in-depth scientific examination of this photograph. Technology has advanced much since they were first looked at nearly a hundred years ago. Surely now is the time for someone to conduct a thorough examination of this last photograph.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity to do it now. It’s just been the 100th anniversary of the photograph being published and some organisation or individual could now do an investigation into that last photograph to prove once and for all, is it real or is it not, one way or the other.”

The negatives of the photographs are held in the collection of the Brotherton Library, which is part of the University of Leeds. An exhibition is planned of their Cottingley Fairies items – including one of the Conan Doyle cameras borrowed from the Media and Science Museum in Bradford – as soon as current lockdown restrictions allow.

When it does get going, a century after the world was still talking about the photographs that Arthur Conan Doyle had presented to the world in The Strand Magazine, could this be the perfect time for 2021 to potentially throw up it’s most astonishing surprise yet… proof that fairies do actually exist?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks