Trump vs Roosevelt: How the US once led a fight against a deadly virus but is losing it today

When polio was the most feared disease 70 years ago, the US spearheaded the battle for a vaccine. Compare that effort with Trump’s bizarre and chaotic response to the pandemic, which has produced a death toll in the US higher than anywhere else in the world. By Patrick Cockburn

The two epidemics that have most terrified the US in the last 100 years are Covid-19 today and the devastating polio epidemic that ravaged the country for 40 years between the New York polio epidemic of 1916 and the successful use of the Salk vaccine after 1955. The polio virus caused extreme terror because it was highly infectious, crippled or, more rarely, killed children and seemed impossible to stop. Prior to mass inoculation, it appeared in waves that became bigger and more lethal as the years went by. The current pandemic is frequently compared to Spanish flu in 1918-19, which led to the death of millions, but it was of short duration. In many respects, the coronavirus epidemic has closer similarities to polio because in both cases many are infected by the virus, but only a small proportion die or are disabled.

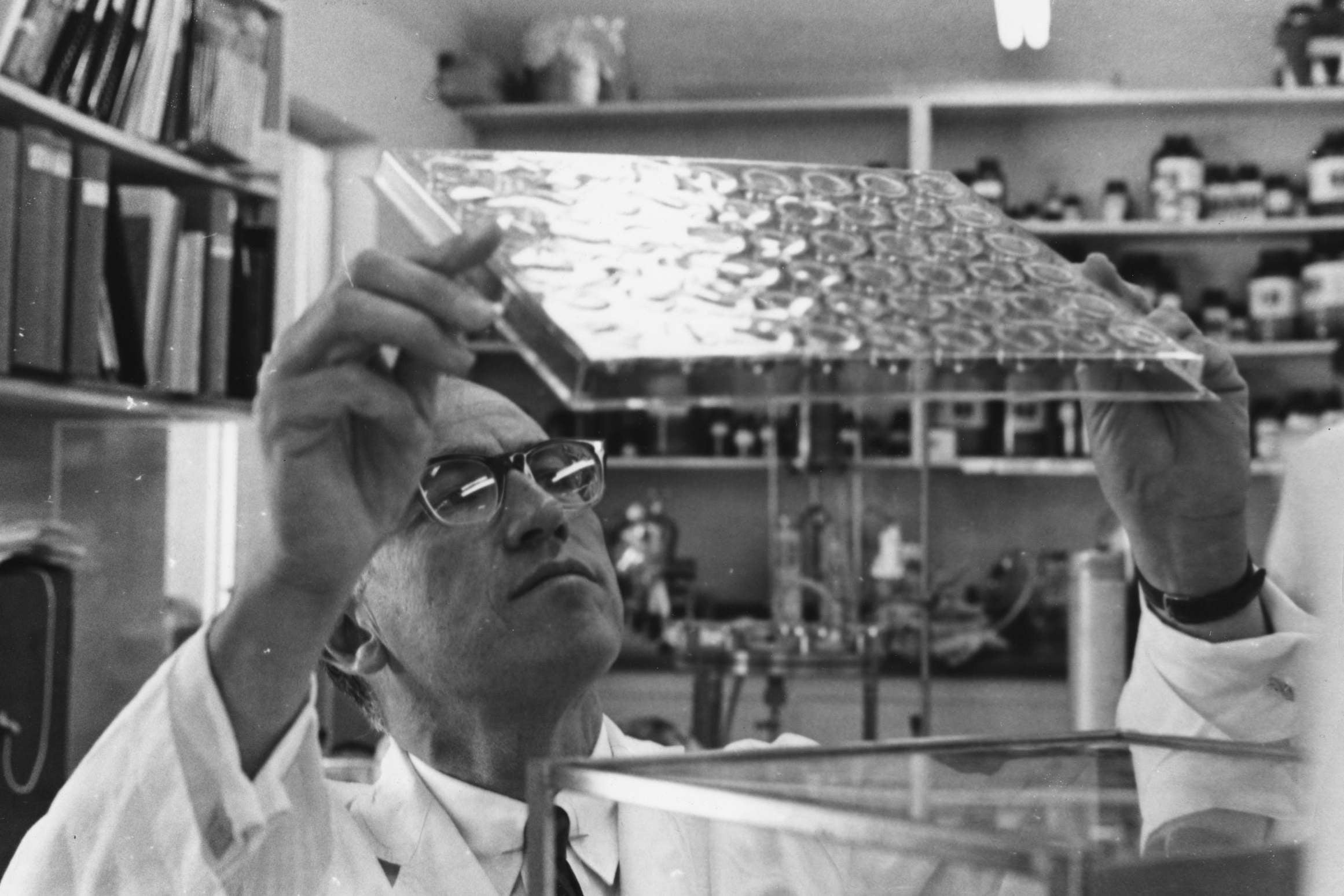

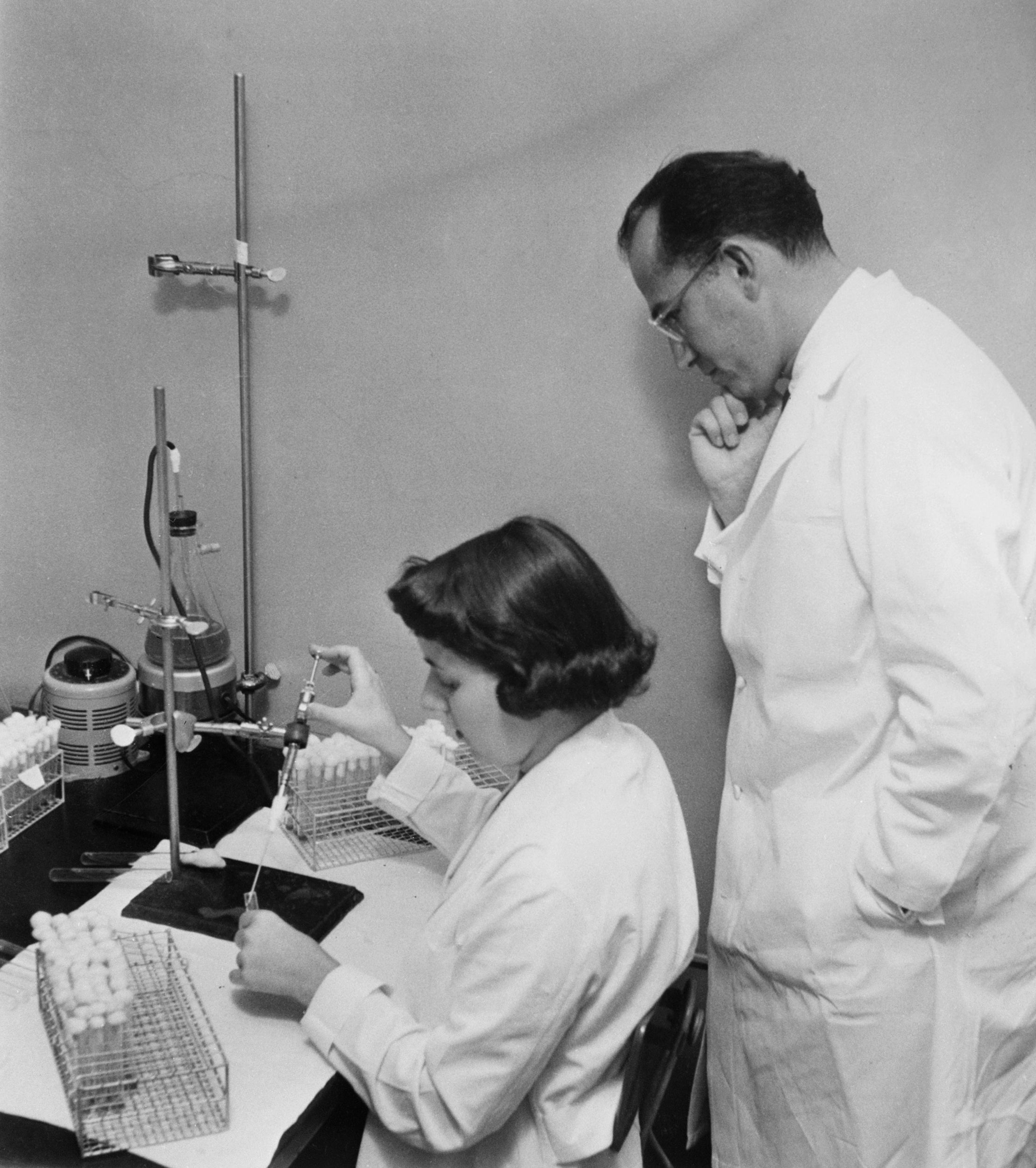

The discovery of an effective polio vaccine was one of the greatest scientific achievements of the US in the 20th century, comparable to landing a man on the moon – and of much more use to humanity. Success did not come easily and there were many false steps: the life-cycle and mode of attack of the polio virus, in so far as a virus is alive, turned out to be very different and more complicated than originally supposed. Jonas Salk, who was to be followed several years later by Albert Sabin, received great acclaim for eliminating the disease through developing different vaccines. But their ultimate success was built on the work of other scientists and laboratories that had contributed to understanding the deadly virus.

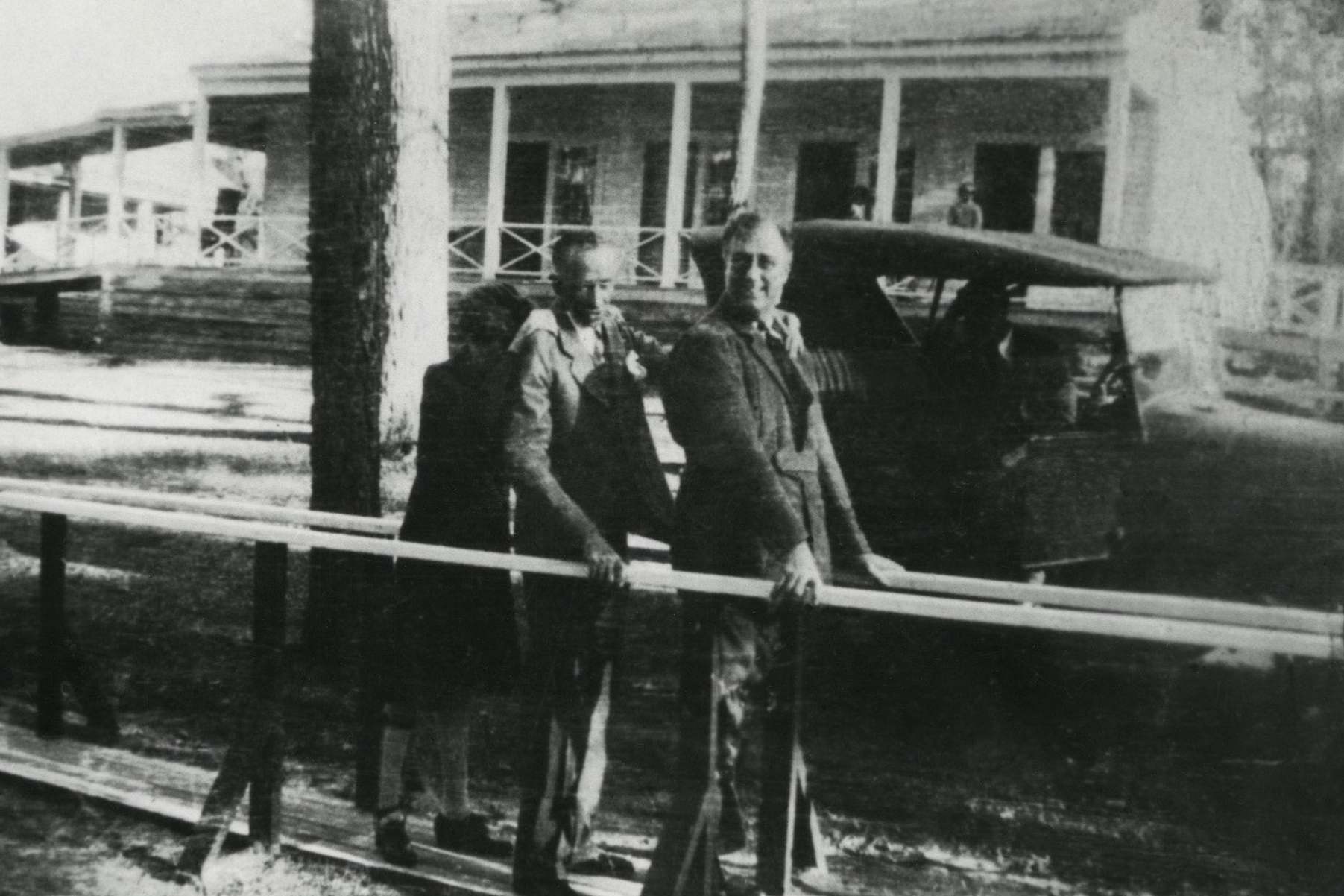

Politicians and scientists combined to conquer polio. Popular awareness of the illness, and scientific research into treating it, was supported by President Franklin D Roosevelt. He himself had been crippled by polio in 1921 when, aged 39 and a rising political leader in New York, he was infected and became wheelchair-bound for the rest of his life – though he sought to conceal the extent of his disabilities from voters. He organised a decades-long campaign to warn people of the threat posed by the disease and raised vast sums to fund research into discovering a vaccine. In 1938, he set up the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (another name for polio), though, as he had discovered to his cost, the virus could also cripple adults. It was this organisation that later launched “The March of Dimes” after an appeal for all Americans to contribute a dime, or 10 cents.

Salk and his team developed a safe inactivated (killed) injected polio vaccine in 1953, which was successfully tested in 1955. When the results of the tests were announced on 12 April, the 10th anniversary of FDR’s death, church bells rang out in celebration across America. The vaccine was used the following year to stop a polio epidemic that was gathering pace in Chicago: medical teams took over empty shops and any other space available to administer injections and achieve mass inoculation. Within a couple of years, the number of polio cases in the US had fallen by between 85 and 90 per cent.

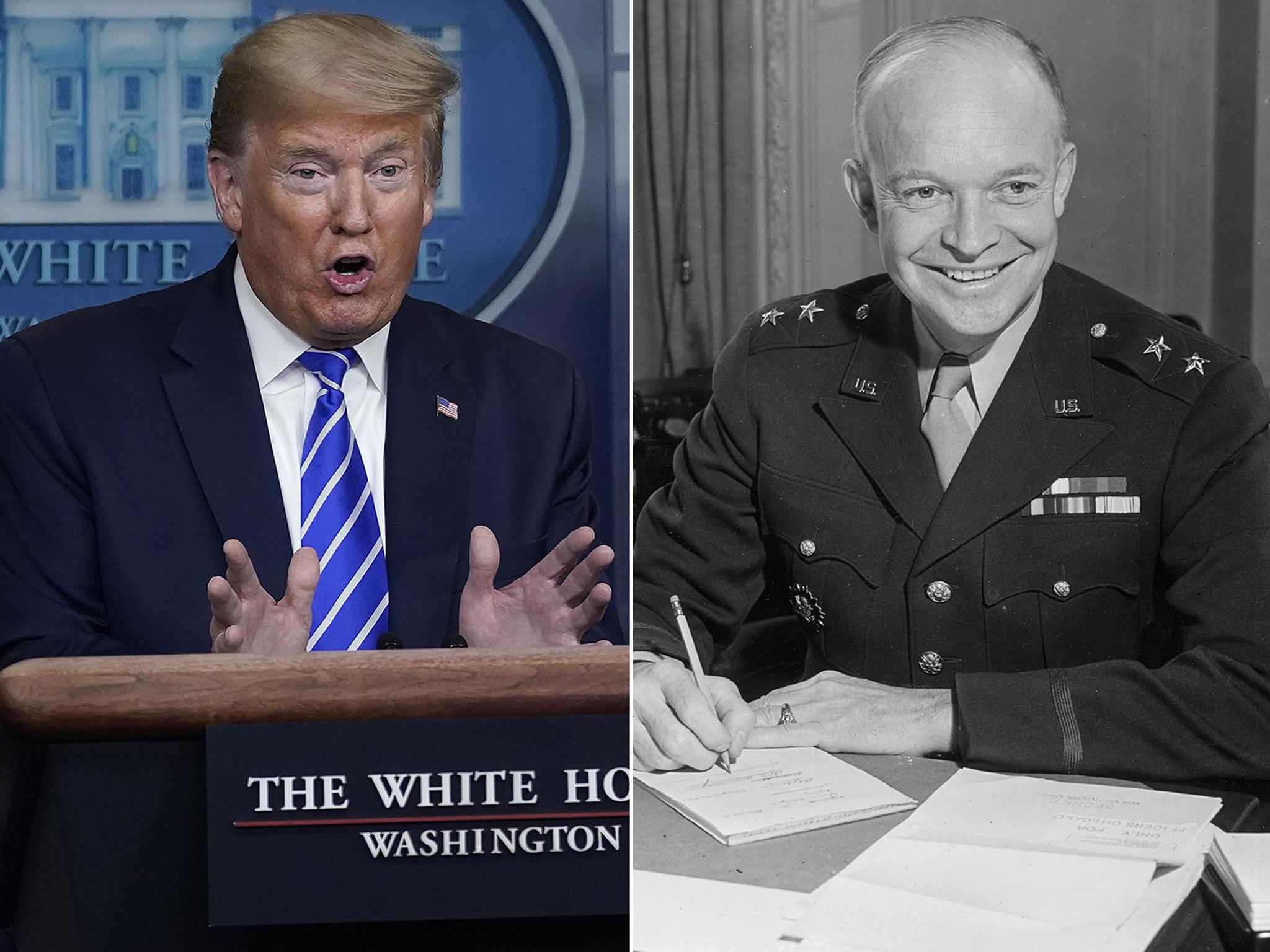

Polio was a highly international disease from the moment it first took epidemic form in the late 19th century, with countries as distant as Sweden and Australia badly affected. The response to the illness was also international. The US invented the ‘iron lung’ in 1929 to keep alive polio victims who could not breath, but the first ICU – possession of which is seen as essential to limit Covid-19 fatalities – was developed in Copenhagen during a polio epidemic in 1952. The US was at the forefront of research from the beginning and, though it was at the height of the Cold War, President Eisenhower pledged that the US would make vaccines discovered by American scientists available to the rest of the world.

When the “live” attenuated vaccine developed by Salk’s rival, Albert Sabin, was mass tested, the tests took place in the Soviet Union. The Sabin vaccine had the advantage that it could be taken orally on a lump of sugar (until dentists objected) and dealt with three different types of polio at the same time. By 1962 it had replaced Salk’s vaccine because it was easier to administer and was also cheaper, in part because Salk and Sabin each refused to patent their discoveries. Today polio has been eliminated from almost all the world and only survives in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria because Islamic fundamentalists oppose inoculation campaigns.

Compare the US-led campaign against polio in the 20th century with its response to the Covid-19 pandemic in the 21st century. In the first case, the US led the way, while in the second it has demonstrably lagged behind with a far higher death rate per head of population than most other countries. At the time of writing, nearly 84,000 Americans have died of coronavirus, far exceeding the death toll in Asia or Europe. Politically and medically, the US failure to bring the epidemic under control is one of the most striking features of the pandemic.

I was unlucky to get polio after the Salk vaccine had been discovered, but before it was distributed in Europe. I believed later that I had been disabled by one of the last of the epidemic diseases

Compare President Trump’s response to Covid-19 with that of Roosevelt and Eisenhower when dealing with polio. First Trump played down the gravity of the disease, saying that it was much like mild flu, and denounced US politicians who took stringent measures to cope with it. When it came to a vaccine, he promoted an anti-malaria tablet that was useless against coronavirus and suggested injecting a disinfectant as an effective antidote. Instead of international cooperation against a global threat, he backed a conspiracy theory that claims that the Covit-19 virus had come from a laboratory in Wuhan, China, though his own intelligence agencies and scientists said there is no evidence for this.

Epidemics fuel fear and frightened people look for somebody to blame, foreigners often providing a convenient scapegoat. In the New York polio epidemic of 1916, newly arrived immigrants from Naples were suspected of spreading it, as were dogs and cats who were hunted down and killed in their thousands. Xenophobia remains a good card to play in such fraught times. The National Republican Senatorial Committee sent out a memo in April saying that “Coronavirus was a Chinese hit-and-run”. It advises its candidates to go on the offensive: “Don’t defend Trump, other than the China Travel Ban – attack China.”

I have been interested in the handling of epidemics by governments and the medical profession since I contracted polio at the age of six in Cork in Ireland in 1956. It was one of the last pre-vaccine epidemics and the majority of those paralysed were children, though adults were not immune: I did not know this at the time, but one victim was my brother-in-law, Michael Flanders, a singer and actor responsible for bestselling records such as A Drop of Hat, who had been at university in 1939 when he was called up to the Navy and, in 1943, contracted polio that permanently confined, him to a wheelchair.

I was unlucky to get polio after the Salk vaccine had been discovered but before it was distributed in Europe. I believed later that I had been disabled by one of the last of the epidemic diseases in the developed world, which had already developed vaccines against smallpox, cholera, scarlet fever, typhus and tuberculosis. It has turned out over the last six months that I, along with almost everybody else, was being over-optimistic about the end of the great epidemics. The globalised world might have eliminated or brought under control many lethal viruses and bacteria, but others were evolving or were already in being and they could still do terrible damage.

Polio is an example of a virus that used modernisation for its own ends. It has had a long history causing paralysis in individuals, but it was only at the end of the 19th century that it started to cause epidemics. This mystified contemporaries who were struck by the fact that outbreaks were taking place in the most modern parts of the most modern cities. Among those badly hit, were better-off districts in New York, Chicago, Melbourne, Copenhagen, Stockholm. Sometimes polio was referred to as “a middle-class disease” because children in the slums and poorer neighbourhoods were seldom infected. This was probably because they caught the virus as babies when self-immunised by their mothers’ antibodies. But in places where there was a clean water supply and efficient sewage disposal, children became vulnerable.

Salk and Sabin finally succeeded in eliminating polio, but it had taken half a century for scientists fully backed by public opinion and supported by Washington to do so

In Cork city this was certainly the case during the epidemic there. Dr Gerald McCarthy, the medical officer for the county, said: “The higher the standard of living, the greater the tendency towards the disease. Generally, the well-washed and the well-laundered children are the most susceptible.” Maureen O’Sullivan, a Red Cross nurse who drove an ambulance, told me that “80 per cent of the victims came from affluent or semi-affluent families”.

My brother Andrew and I probably caught polio for a slightly different reason: our parents thought that we would be safe from the epidemic because we lived in an isolated house in the depths of the Irish countryside. But this meant that we were not self-immunised and, fatally, we were not entirely isolated because our father was travelling backwards and forwards between Cork and London. Isolated communities and islands have always been vulnerable to the polio virus: one of the earliest epidemics was on St Helena in the south Atlantic and another took place on the Australian island of Tasmania.

The polio virus and coronavirus differ in the type of victim they target: in the case of polio the most vulnerable were the very young and the un-immunised better off. In the case of Covid-19, it is the exact opposite: people who are old, ill and poor are worst hit. But both viruses share a common feature in that they can infect many people who then show few or no signs of illness, but they become unwitting carriers of the disease.

Doctors past and present never quite seem to take on board that people have a deep-seated fear of infectious illnesses and they instinctively keep away from them. There is no point in telling them that the infection is impossible to avoid or, if they are infected, their age group makes it unlikely that they will suffer serious harm. People will naturally self-quarantine if threatened by a dangerous infection. In Britain in March, many were self-isolating and keeping away from large gatherings before the government told them to do so.

Polls show that the lockdown is propelled less by government instructions and more by a general fear of contracting coronavirus. The fears and the same response were evident in New York a 100 years ago as residents tried to seal off their districts with armed guards and guards on trains refused to carry children below a certain age. By banning travel from China to the US at the end of January, Trump appealed to the same deceptive instinct whereby a threatened population tries to exclude a virus or a germ as if it were a human enemy.

As the pandemic spread this year, I was struck by the parallels with my own experiences with polio over half a century earlier. The polio and Covid-19 viruses might behave in different ways, but their onset always creates intense fear. The damage they do, particularly to the respiratory system, is sometimes similar and the means used to save the patient is the same, with the ventilator replacing the “iron lung” that was invented in 1929 to save polio victims who could not breathe. ICU units were first created in Copenhagen to treat polio victims. Then as now repeated hand-washing was recommended as the best way of fending off the virus.

Today there is a panic-fuelled rush to develop a vaccine against coronavirus, but here the precedents are not good because, for all FDR’s power, the Salk and Sabin vaccines took a long time to develop. When the polio virus was first identified in an epidemic in Vienna in 1908, it was believed that an effective vaccine would soon be discovered. Yet it was only in the 1930s that two of the three polio strains were first distinguished and one of the first vaccines turned out in 1935 to be useless or fatal to those to whom it had been administered.

Salk and Sabin finally succeeded in eliminating polio, but it had taken half a century for scientists fully backed by public opinion and supported by Washington to do so. One of the most chaotic and fragmented US governments in history is now trying to repeat this success.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments