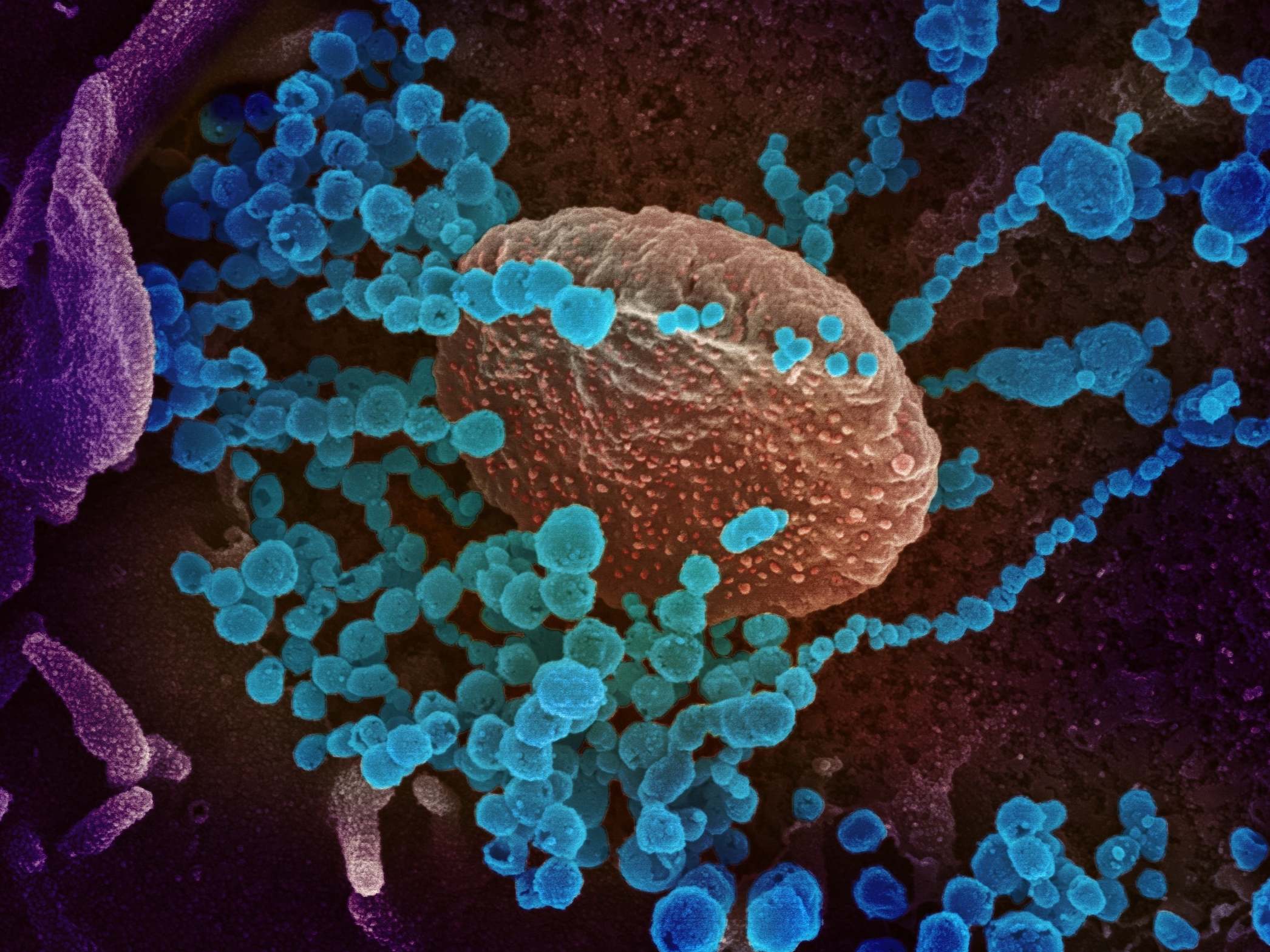

Coronavirus and the political fallout for the people of Iran

The outbreak of the virus and the spread of ‘false rumours’ has thrown a spotlight on just how little the Iranians trust those in authority on important issues, reports Kim Sengupta

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.My corona test is positive ... I don’t have a lot of hope of continuing life in this world,” wrote Mahmoud Sadeghi on Twitter. He went on to ask the head of Iran’s judiciary to release those in prison for political crimes to avoid chances of contracting the disease, and allow them to be back with their families at such a deeply worrying time.

The message from the member of the country’s parliament, Majlis, was an example of how the disease has become not just a hugely serious issue of health, but one of politics and the social contract between the state and the citizens. It has become a conduit for a fierce debate, which is now going on around the country – just how much do people trust those in authority on important issues.

There is another link to politics. Three more politicians have been infected with Covid-19, leading to speculation on whether the carrier could be someone who moves in high government circles. Masoumeh Ebtekar, the first female cabinet member in the country, became internationally known as the spokeswoman for the hostage takers at the US embassy in 1979. She is now the vice-president for Women and Family Affairs and, according to unconfirmed reports, attended a cabinet meeting with President Hassan Rouhani before her diagnosis.

Mojtaba Zolnar, chair of the National Security and Foreign Policy committee, assured the public in a statement that “there is nothing to worry about. I am in quarantine now. God willing our people will defeat the corona.” The deputy health minister, Iraj Harirchi, looked feverish, coughing with sweat on his forehead while appearing at a press briefing to criticise “alarmist” reporting about the spread of the disease.

A day later Harirchi announced he had been tested positive for the virus and was getting medical treatment and going into isolation. The journalists who had attended the briefing were furious that they may have been exposed to coronavirus, adding to the rising tide of criticism over official conduct and the deluge of allegations, some of them wild conspiracy theories, in the social media.

While covering the election I found that most people blamed their troubles on what they saw as the corruption and incompetence of domestic politicians as much as the US president

The official reaction has been a crackdown on “false rumours”. Twenty-four people have been arrested for material they had posted online and another 118 "let go”, announced Vahid Majid, head of the country’s cyberpolice force. But pressure has also led the government to look at complaints from the public that they had been misled.

Before the arrival of Covid-19 got publicity, the trust deficit was already evident at last week’s parliamentary election, one of the most important in its recent history, and one which will have repercussions beyond its borders: the turnout for the capital, Tehran, was just over 25 per cent, and 42.5 per cent for the rest of the country. These were the lowest figures for any election since the Islamic revolution which overthrew the Shah.

The reasons for the electorate being disillusioned were, as people saw it, the failure of the reformist government of Rouhani to deliver on promises of widespread social and economic reforms, which won it a sizeable mandate in the election three years ago.

That failure was largely due to Donald Trump pulling out of the deal between international powers and Iran over the country’s nuclear programme and imposing punitive sanctions. This has resulted in the economy being left in a parlous state. But, while covering the election, I found that most people blamed their troubles on what they saw as the corruption and incompetence of domestic politicians as much as the US president.

Time and again the complaint was a version of “you cannot believe a word they say”. This is a refrain, of course, one hears about the establishment in other countries, including in the west, and the hardliners gaining control of the Majlis could be seen as another version of populist triumph.

The volatile mood was seen in the anger and grief at the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, by the Americans, and the street protests over the shooting down of the Ukrainian airliner. The anger was due to the government initially denying any responsibility for the plane disaster. Coronavirus has arrived on the back of this perfect storm and is being held up as another example of official narratives that cannot be believed and incompetence being covered up.

The accusations from the public are at times contradictory. I saw an example of this when an official said to me before polling day that voter numbers are likely to be down because of the contagion. I relayed this to a young woman I know, and her friend tweeted that the government was exaggerating the threat, trying to hide the fact that people will keep away because of political discontent. A few days later the same young people would claim that officials were criminally trying to minimise the true extent of the outbreak.

The interior minister implied that it was understandable that the rising toll of infected and dead would keep people from the polling stations

But then, the establishment was also making contradictory statements. The supreme leader, Ayatollah Khameini, and President Rouhani had repeatedly exhorted the electorate to vote, declaring that a failure to do so would be used by the US and its allies in their own nefarious aims of undermining Iran.

After the turnout figures emerged, Khameini charged the media, national and international, with inflating the risks posed by the virus. But then, announcing partial results, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, the interior minister, implied that it was understandable that the rising toll of infected and dead would keep people from the polling stations. “We believe that the number of votes and the turnout [under the circumstances] is absolutely acceptable,” he insisted.

The statistics of those affected is a matter of heated dispute. The official account is that there are 245 cases of infection reported with 26 deaths. But specialists dealing with Covid-19 point out that the numbers of dead suggest that far more people have contracted the virus.

The deputy health minister, before he fell ill, was to deny the claim by Ahmad Amirabadi-Farahani, member of parliament for Qom, where the outbreak began, that 50 people had died in that city alone and the authorities were carrying out a cynical cover-up. Harirchi declared that he would resign if it was proved that even half that number had died.

The secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran, Ali Shamkhani, had asked the country’s prosecutor general, Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, to “check the validity” of the allegation. This may have been an attempt to establish facts, or it may have been a veiled threat against the MP. If it was a threat, it did not work. Qom, which Amirabadi-Farahani represents, is one of the holiest of Shia cities and is a bastion of the religious establishment. He is a former officer in the Revolutionary Guard, who had fought in the war against Iraq and took part in the siege of Basra.

The MP refused to retract his claim, saying he had sent a list of 40 people who had died to the health ministry and now awaited Harirchi’s resignation.

Medical companies claimed that they were being blocked from getting testing kits due to American sanctions

The initial reports about the arrival of coronavirus led to amusement in Tehran. A customer in a cafe told the cleaner: “Look over there, I can see a bit of corona.” A social media posting had a woman unexpectedly pregnant saying “it may of course just be a bit of corona”. Mohammad Javad Zarif, the foreign minister, shaking hands with his visiting Australian counterpart Alexander Schallenberg, laughed: “I swear to God, I am not infected with this new coronavirus.”

But the mood began to change with more cases emerging with, as in other places affected, supplies of face masks, gloves and hand-sanitisers beginning to disappear from the shops and prices shooting up for the stock left. Iran had donated three million face masks to Beijing “as a sign of the long-term and traditional friendship between two countries” when the virus first appeared in China. Chinese companies have also been buying up Iranian supplies. The Iranian government has now banned the export of face masks for three months and ordered factories to ramp up production.

Medical companies claimed that they were being blocked from getting testing kits due to American sanctions. “Many international companies are ready to supply Iran with coronavirus test kits, but we can't send them money,” said Ramin Fallah, a board member of Iran's Association of Medical Equipment Importers. Washington denies that sanctions affect medical products as there is an exemption for humanitarian supplies. But processing payments is extremely difficult, the Iranians point out, because banks are unwilling to risk falling foul of secondary US sanctions on financial transactions.This problem should ease after the announcement by the US on Thursday that it had granted a licence to allow specified humanitarian trade with Iran’s central bank, which had been placed under sanction, through a Swiss aid channel.

There was now less amusement and more alarm. I have had interesting visits to Qom in previous trips to Iran, and when I mentioned going there (albeit knowing what the reaction was going to be) there were no takers among those who had been exchanging jokes about the virus of my request to accompany me. The trip did not take place. I was quite relieved.

The mood became even more tense as international airlines began to cancel flights. The seats in the remaining ones were disappearing at a fast rate. But not all could get out even if they had tickets. The Iranian passengers on the flight I was on to Muscat, were told that the Omani government had temporarily banned entry to Iranian nationals. The distraught passengers protested, waving the tickets they had paid for, but that changed nothing, the plane took off without them.

Several other countries in the region have taken the same policy. Four neighbouring countries – Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Armenia – have closed land borders. Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain and UAE have banned travel to and from Iran. These are the countries Iran is dependent on for trade after US sanctions effectively cut it off from the global economy. Some of them are countries where a lot of Iranians live. What had happened has led to a sense of greater isolation among people whose hopes of opening up to the outside world had dissipated with the near collapse of the nuclear deal. At the same time acts such as the killing of General Soleimani and seizure of tankers in the Gulf had raised the spectre of war.

I met Arash and Sara Gharabagi at the coffee shop of my hotel the day I left. The couple, who live in Turkey, had come to Tehran to see Sara’s 68-year-old mother who was unwell – “but not with coronavirus”, Sara stressed hastily. The Turkish Airlines flight had been cancelled and they were deeply worried about how they were going to get back to their young son and daughter who were being looked after by friends in Istanbul.

“What has happened has come as a shock,” said Sara. “We must go back to our children, but now we have to find some other way to go back, we are looking at all kinds of options. But at the same time we are so worried about our parents who are here, what is going to happen to them with the virus? Supposing we don’t see them again. I know other people around the world are suffering, and we are not special. But we are very nervous about what is happening, very nervous.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments