Crossing state lines for an abortion while America locks down

Across America, conservative governors in a number of states used the coronavirus pandemic as an excuse to temporarily ban abortion. Holly Baxter reports how anti-choice evangelicals have quietly enmeshed themselves in the US government — and what the permanent effects of this ban might be

Four months before the coronavirus pandemic caused chaos across the country, Melissa* and Joe* found out they were having twins. “It was a very much-wanted pregnancy,” Melissa tells me down the phone from her home just outside of Austin, Texas. “We’d tried for a while.” But the first scan brought some bad news. “Twin A – we called them Twin A and Twin B – had severe abnormalities. The heart was outside of the body, things like that. They said it was ‘not compatible with life’. At the time, though, they said Twin B looked good. And after a while, Twin A did pass in utero.”

It was difficult to deal with emotionally, but Melissa and Joe held themselves together and pinned their hopes on Twin B. It’s not unusual for one twin to die in utero; usually, that foetus is safely absorbed by the body and the other can carry on growing healthily. To put their mind at ease about Twin B, Melissa’s doctor offered an early anatomy scan at 16 weeks – and, despite previous assurances that that twin looked fine, it was bad news.

“It was lethal skeletal dysplasia,” Melissa says. “The ribs were too small and the wrong shape. Twin B would never have lung tissue enough to breathe. They would never be able to draw their first breath.” Instead, if she chose to carry the pregnancy to term, the baby would die as soon as it left the womb, struggling to breathe and then suffocating a few minutes later. The foetus also other foetal abnormalities, according to Joe, including “bowed” and “tiny or unformed bones” elsewhere in the body.

“We were shocked,” Melissa says. “There had been no indications there was anything wrong with B prior to that scan. We’d wrapped our minds around the situation occurring with A, come to terms with that, and thought, ‘B’s still looking good, though’. Then they pulled the rug out from under us.” She pauses, before adding: “To let the pregnancy continue felt really unfair. I don’t believe in bringing additional suffering into the world – I’m not a particularly religious person, but it doesn’t feel right when you know that’s going to be the conclusion. It was the hardest decision I ever had to make, taking the compassionate option to terminate for medical reasons.”

“We had read stories about parents inducing [at full-term in a similar situation] and they said it was the most scarring experience of their lives and the baby just suffers,” Joe adds. “People made comments like, ‘Keep your legs together’. It kinda pissed me off because this was a very wanted pregnancy. It just wasn’t going to survive. And we felt it was unethical to let it suffer.”

Something had happened in between the death of Twin A and the terminal diagnosis of Twin B: Texas had gone into lockdown. State governor Greg Abbott, a Republican, mandated as part of that lockdown that all elective procedures in hospitals should be stopped immediately. Unlike most other states, Abbott – who lists “protecting free speech on campus, ensuring medical care for babies born alive after attempted abortion, banning red light cameras and more” under his “notable successes” on his official website – chose to include abortions in his executive order. His decision was reinforced by state attorney general Ken Paxton. They told Texans that it was because vital medical equipment was needed for doctors and nurses fighting Covid-19, despite the fact that pill abortions can be carried out at home. “We were flabbergasted when we heard there was no way to terminate for medical reasons,” Joe tells me. In one fell swoop, all their options were taken away.

Melissa and Joe had previously supported Governor Abbott. “In other areas, we think he’s been good, made some strong choices. But in this instance, I don’t know,” says Melissa. “I’d hate to think he had allowed himself to be strong-armed into something… I understand you have to provide a united front. Perhaps the situation got a bit away from him, I don’t know.”

Some have questioned whether Abbott and Paxton took advantage of the pandemic situation to advance an ideological agenda. “You know, they did let the situation get politicised,” Melissa adds. “You’re letting a policymaking step come in and interfere between a patient and a doctor. And that policymaker has no medical qualifications. Who are they to say, ‘We believe we know better than the doctors’?”

To let the pregnancy continue felt really unfair. I don’t believe in bringing additional suffering into the world – I’m not a particularly religious person, but it doesn’t feel right when you know that’s going to be the conclusion. It was the hardest decision I ever had to make, taking the compassionate option to terminate for medical reasons

Abbott, a self-described “conservative leader who fights to preserve Texas values like faith, family and freedom”, seemed to have forgotten that “freedom” is supposed to extend to women too. Although his order did make one exception for abortions during the pandemic – the mother’s life being in immediate danger – it provided no option for those with fatal foetal abnormalities. And that left Melissa and Joe in a difficult situation: “It became obvious that no option in the state of Texas would be able to help us. We would have to go outside.”

Once Melissa, Joe and their doctor realised that they’d have to travel for the procedure, they moved quickly. Although Melissa’s life wasn’t in immediate danger, carrying a foetus to full term with lethal skeletal dysplasia is risky and continuing the pregnancy would be both mentally and physically harmful. “We found out [about Twin B’s condition] Monday, then spent the entire day Tuesday calling doctors’ offices and insurance and planning where we were going. New Mexico was our closest option. We were in the car on Tuesday afternoon.”

Austin, Texas to Albuquerque, New Mexico is an 11-hour drive on a good day. Not only that, but going out of state meant going “out of network” on most Americans’ medical insurance – in other words, being forced to use doctors and hospitals which are not covered and having to pay out of pocket. Surgical abortions after 16 weeks in the US usually cost between $8,000 and $15,000, but can also cost a lot more.

More than the money, however, the trip to New Mexico came at a huge emotional cost. “We were very scared. I was pregnant, in a high-risk category, and I didn’t want to contract Covid. We had been quarantining since the beginning of February – full not-leaving-the-house quarantining, curb-side groceries, everything. We had been trying so hard to do the responsible thing and to be mindful.”

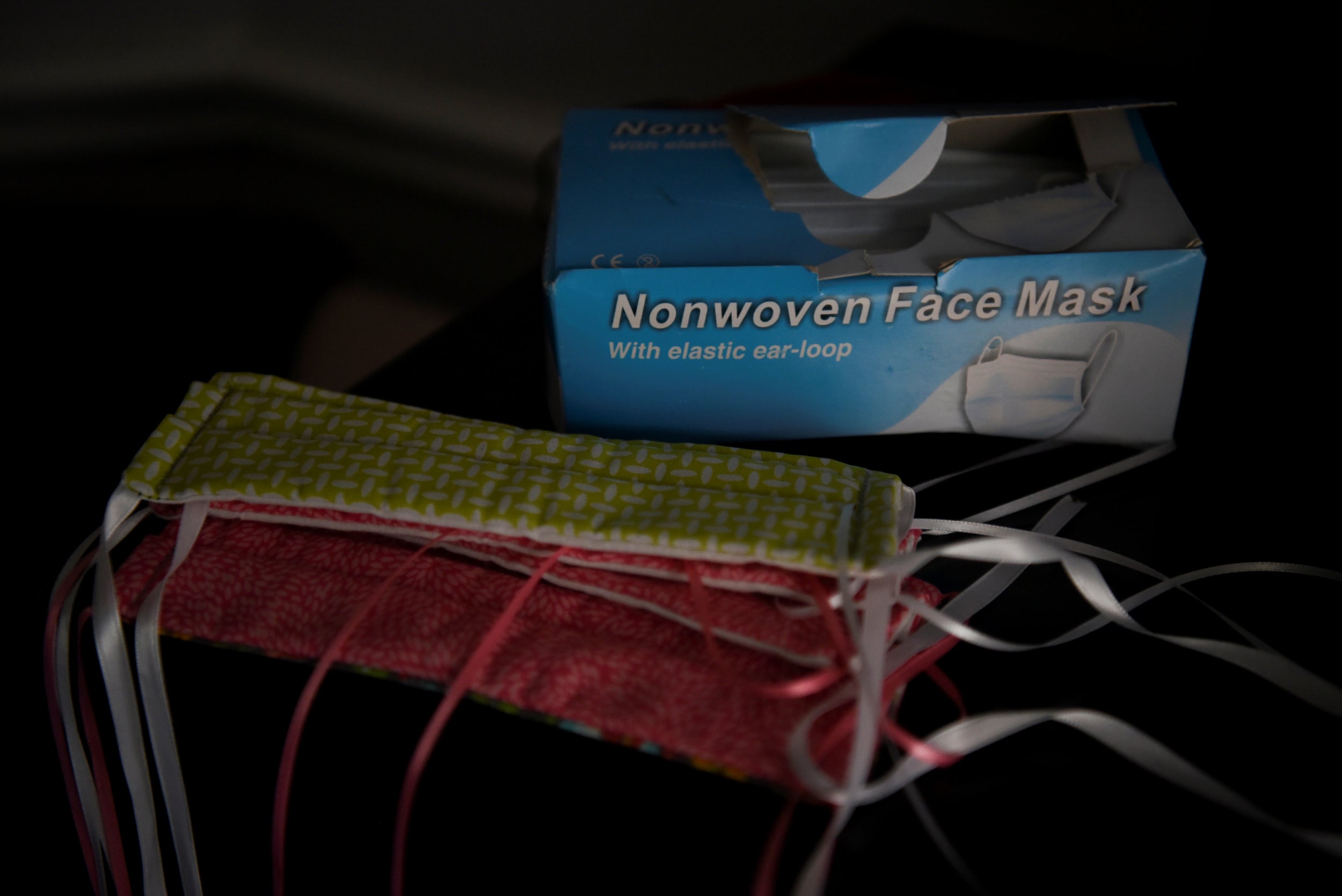

So, forced on a journey across state lines, they stocked up on masks, disinfectant spray, wipes and gloves. They packed up as much of their own food as possible so they wouldn’t have to stop at service stations. They researched hotels, trying their best to filter out the unsafe from the responsible; they did the same with doctors and hospitals. “It was so stressful. I’ve never been to New Mexico. This was choosing healthcare out of the phone book. We’re asking ourselves: ‘Is this one professional? Is this one questionable?’”

Eventually, at the end of a long and exhausting trip, Melissa was able to terminate her pregnancy. She says that she was “pleasantly shocked” by the compassion and the competence of the healthcare staff who cared for her: “I couldn’t have asked for better providers. They said, ‘We’ve seen a lot of women coming from out of state, three or four times the usual amount.’” When she heard that, Melissa says, she knew she’d be happy to talk to the media about her experience: “It was the one thing I felt I had control over in the whole process – diagnosis, options, none of that was up to me. The only thing that stood out as something I had the ability to do was to point out the injustice of the situation.”

You’re letting a policymaking step come in and interfere between a patient and a doctor. And that policymaker has no medical qualifications. Who are they to say, ‘We believe we know better than the doctors’?

Since his election, Donald Trump has delivered on his promise to fill the Supreme Court with anti-abortion judges. After seeing a “Trump 2020” hashtag in Joe’s Twitter bio, how does the couple’s politics jar with some of the decisions the president has made over his first term? Melissa finds the pro-life narrative “artificial”, she says. “I valued the life and the quality and experiences of an infant I was going to have, and that’s why I made my decision. I didn’t want it to know only suffering.” She wishes Supreme Court judges would understand that they are “dealing with people’s lives, individual lives” rather than simply cherry-picked pieces of legislation. “If this was a hot-button issue that involved a man’s body then it wouldn’t be politicised,” she adds.

The pockets of anti-abortion crusaders are deep, and their ability to take advantage of a situation like a pandemic are successful because they are well-organised across the US. Joe tells me that even before he and Melissa found out Twin B was not able to survive, they found themselves backed into a corner. They thought they would have to selectively terminate Twin A, he explains, but were told by their doctor that they would have to travel for four hours to Houston for the procedure because their local hospitals in Austin had imposed strict limits on when they would perform abortions. Nowhere nearby would perform a termination procedure after 13 weeks. “I think rich people donate [to the hospital] on the condition they do not do [late] abortion,” he says (according to multiple sources, he is correct, although no hospital will admit to that on the record).

Under “conscience laws” protected by freedom of religion, hospitals and doctors are also allowed to refuse to perform abortions and even provide contraception if they state that it contradicts their religious beliefs. Invoking these clauses isn’t rare or limited to conservative communities: one particularly shocking example happened recently in New York City, when the tent hospital set up in Central Park for coronavirus patients came under fire for asking local doctors and nurses working there to sign statements agreeing that they were against equal marriage. These statements were, according to the health workers involved, written up by the evangelical Christian charity Samaritan’s Purse, which used its funds to supply most of the medical equipment used in the tents. Its altruism came at a high price.

And it isn’t just creating de facto bans of abortion through inaccessibility in conservative states that anti-abortion campaigners specialise in, either. They are frighteningly adept at public relations and at creating the appearance of consensus. Almost 10 years ago, I wrote about the protesters outside an abortion clinic in west London for another newspaper; they had taken up residence in a particular spot in Ealing, and sat in camping chairs throughout the day holding some of the most graphic signs – supposedly depicting the body parts of aborted foetuses – I’d ever seen in my life. When I approached the protesters and asked to speak with them as a reporter, I expected them to be aggressive zealots.

Instead, I found many of them to be pleasant, mild-natured people. A number of them told me they were recent immigrants to the UK, who had been helped out with housing and moving costs by a local church. In return, it had been strongly suggested to them that they should take the signs and stand vigil outside the reproductive health clinic. Some of them told me they’d never even really thought that much about abortion before, although as Catholics they had a vague conception of it as morally wrong. One said to me that she’d heard the group connected with the church was “funded by a rich American”. I was never able to verify all of that information, but the group that provided the signage for the group, 40 Days for Life, lists its CEO as an American “pro-life speaker and author” and Fox News regular called Shawn Carney.

I admit Norma was for me a kind of trophy – a beloved one but a trophy nonetheless. We held her up, showed her off, paraded her around. What we didn’t do was listen deeply to her pain

Similarly, in Alabama last year, I met anti-abortion protesters who proudly told me about the large amounts of money they were able to give women who decided not to go ahead with terminations after being “turned around” by them on the sidewalk. These campaigners have a long history of paying for women’s medical expenses throughout their pregnancies but often fading into the background after the baby is born. Such self-described pro-lifers will tell you that many of them used to be doctors or nurses who helped perform abortions; that after a while, people involved in reproductive healthcare will “see the light”. One of their most crowed-about success stories was, up until this week, the case of Norma McCorvey, otherwise known as Jane Roe of the famous Roe v Wade case which made abortion legal across the US under a Supreme Court ruling in 1973. Unfortunately for them, it seems that McCorvey’s conversion wasn’t all it seemed – and she elected to talk.

From 1995 she said she had changed her mind about abortion, that she should never have brought the case to the Supreme court, that she regretted it. Pro-choice campaigners were aghast when Roe – who was pregnant with her third child when she was refused an abortion in Texas, and said that she had been raped – turned her back on her own case. But a documentary released on 22 May of this year called AKA Jane Roe includes what McCorvey herself refers to a “deathbed confession”. She claimed that she only publicly denounced abortion because she was paid handsomely by wealthy evangelical groups. “I took their money and they put me out in front of the cameras and told me what to say,” she said. “It was all an act … If a young woman wants to have an abortion, that’s no skin off my ass. That’s why they call it choice.”

Even more surprisingly, one of the key leaders involved in that evangelical movement, Reverend Bob Schenck, who claims he was personally involved in getting today’s equivalent of $500,000 paid to McCorvey, responded to the documentary with a self-critical blog post claiming that he regrets his involvement in pro-life efforts to “turn” McCorvey, including manipulating her, turning a blind eye to her vulnerabilities and alcohol abuse, and convincing her to break up with her much-loved partner, Connie.

“When Norma was inebriated, she would harangue me and others for using her in our fundraising letters but not giving her an adequate ‘cut’,” Schenck wrote. “She was right. Her name and photo would command some of the largest windfalls of dollars for my group and many others, but the money we gave her was modest. More than once, I tried to make up for it with an added cheque, but it was never fair.” After pressuring her into ending her relationship with Connie because “homosexuality is a sin”, he adds: “She eventually did leave Connie, who would die years later alone and in a nursing home. I knew Norma continued to love Connie. My callous part in their breakup will always be one of the worst sins I’ve committed against two human beings.”

He added: “I admit Norma was for me a kind of trophy – a beloved one – but a trophy nonetheless. We held her up, showed her off, paraded her around. What we didn’t do was listen deeply to her pain.” Several prominent senators and 50 anti-abortion religious leaders worked alongside him to make sure she became an emblem of the pro-life movement, he claimed. The money kept rolling in, and the stakes kept getting higher. McCorvey was such a PR win that they couldn’t afford to let her go.

Yet it is important, when discussing the issue of abortion, not just to talk about the cases of Melissa or of Norma McCorvey, the fatal foetal abnormalities during much-wanted pregnancies and the victims of rape. Abortion is a private decision made by a woman about her own body, or it should be. When male lawmakers (because they are almost exclusively male) wait in the shadows for an opportunity like the coronavirus pandemic to present itself and then pounce with restrictive legislation, they make the US an unsafe place for anyone to live in. And when they stand by spurious claims and nonsensical reasoning – that “medical supplies are needed for people with Covid-19” or “negative coronavirus tests are needed before any abortion” – they insult the intelligence of the American population.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is currently suing the state of Arkansas over its negative test requirement; if it wins – which is likely, given its history in successfully suing a number of states over similar laws – then it will be the taxpayers of Arkansas who pick up the cost due to the ideologically driven actions of a handful of evangelical politicians.

A newly unemployed 24-year-old college student in Texas told NPR recently that she had been forced to drive herself for 12 hours to Denver, Colorado, with her best friend to get hold of an abortion pill after she found out she was 10 weeks’ pregnant while Governor Abbott’s executive order was in place. On the way back, they stopped briefly in a motel and feared she would miscarry in the car. They were afraid. They knew they’d been potentially exposed to coronavirus. Their 24-hour round trip was stressful and exhausting. They could have potentially brought infection from another state into Texas.

Abbott’s order was overturned, and abortion is now legal in Texas again – albeit with the restrictions pro-choice campaigners were never able to overturn, such as a mandatory 24-hour waiting period and sonogram, as well as reading materials about medical risks, adoption as an alternative, and foetal development, which the ACLU warns contain false information. It’s unknown how many pregnancies will have continued against the wishes of the mother; how many people who could have had abortions now can’t, due to time limits; how many women will give birth to children they don’t want, can’t support, or which are extremely disabled or dead in a few months’ time.

There is little recourse for people who cannot afford to feed the children they didn’t want to have, and a dearth of affordable mental health support options across the states involved for people whose sick children die shortly after birth. There is, however, a much-celebrated bill in Texas which guarantees medical care for babies who are “born alive” after an abortion attempt – the same bill mentioned on Governor Abbott’s website. The most recently available public data shows the number of instances this happened up to 2016. The number is zero.

* Names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments