Could coronavirus make university education fairer?

In the coming months, Covid-19 is going to force us to try out virtual teaching on a mass scale. If down the line it leads to students being taught by the brightest and best, shouldn’t we embrace it? Steven Cutts isn’t so sure

I remember thinking during my first few days at Imperial College London that this great institution was supposed to change you profoundly, to turn you into something better – namely a graduate. How on earth was that going to happen? What were they really going to do to you over the course of three years that would make you in any way different from the person you were to begin with?

It’s not an easy question to answer, but we assume these things to be true. There’s also not much point in pretending that Imperial wasn’t an elite institution, because it was. They weren’t that strong on presentational skills there, and you don’t see a lot of alumni in the House of Commons or on any of the popular TV shows, but it remains a top university, available only to a limited few. Again, another assumption.

But in the future, many of our assumptions about education will change. If the coronavirus keeps us all indoors, they’ll have to – and pretty sharpish.

Take a trip to an upmarket electrical shop. We’re starting to see something new there: the 100in plasma screen. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that sometime soon, a 100in 8K TV screen will become the norm for your average bedsit. Beyond that, it isn’t hard to imagine a world where it’s routine to fill at least one wall of a room with a very-high-resolution plasma screen (possibly all four walls), possibly with a circumferential curve that enables you to avoid the issue of corners.

Somewhere between a Skype call and an 8K wall or two in your spare bedroom, there will come a time when you can glance up from your desk and see a vision of your office that is almost indistinguishable from the real thing. In particular, an image of a colleague that includes their entire life-size body. If you decide to attend a meeting as a virtual presence, sitting in an individual chair, the only thing you won’t be able to do is reach out and shake hands with the people around you. The way things are going, this might actually be an advantage.

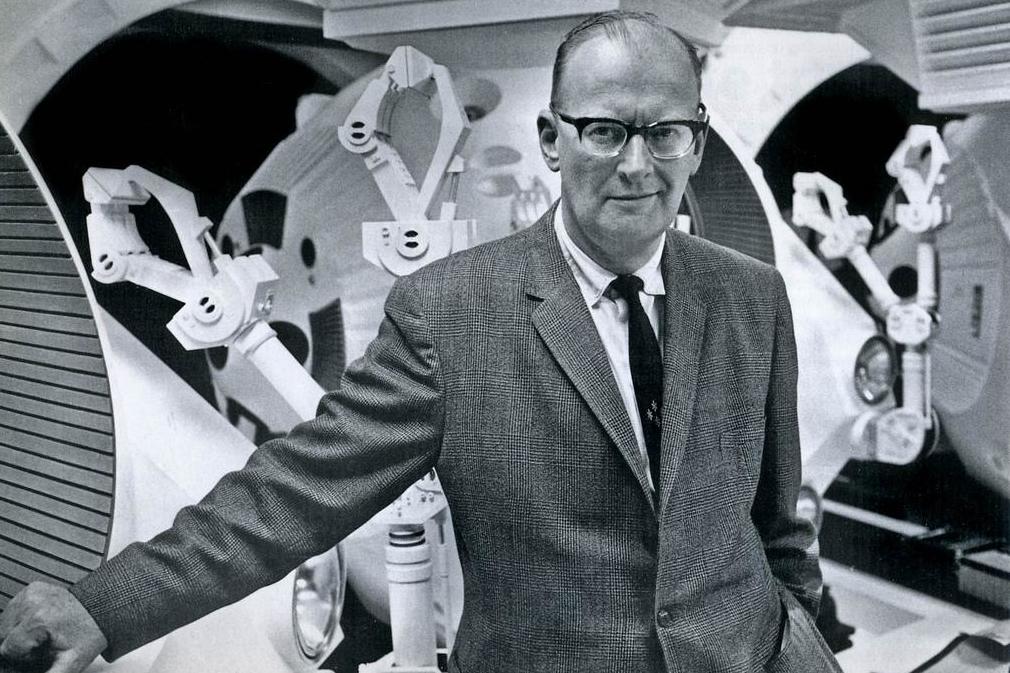

This sort of remote theme has been around since the 1970s. The British writer and visionary Arthur C Clarke talked very loudly about our hi-tech future, and as a kid I assumed that by now most office-based work would be done from home. It isn’t, although the arrival of Covid-19 is quickly altering our perspective on that one. I’d be the first to admit that working at home has its limitations. Even if you’re stuck in an environment where you don’t actually get on with your colleagues, it’s actually quite difficult to keep it all together on your kitchen table. If your work role involves supervising a group of other people, it’s difficult to know what all the people under your command are actually doing, and it’s important to remember that not everybody can do things on their own.

Supposing we were able to film every lecture and every tutorial at Harvard and Oxford and make them available online. What reason would anybody have to feel excluded?

Full-scale video conferencing, of the type that Clarke envisaged, had an unexpected surge in the aftermath of 9/11. At the time, there was a sudden slump in business travel, but an awful lot of businesses still wanted to keep in touch. The early 2000s was a different era, and the technology side of things has moved on since then, but it seems Covid-19 could be taking us there again.

Sometime soon, an awful lot of the standard home office environment is going to be fully screened, but it remains to be seen to what extent this will truly affect our work. As far as power generation goes, it seems reasonable to assume that in the future, almost every new house will become a mini power station with compulsory panels on every roof. In a way, we’ll be moving the power-generation process away from some central machine and out to each and every home. In the same way, it has long been suggested that the idea of some massive central office block will become a thing of the past. Think about how much money your employers are paying per square yard for the desk you usually sit at. Wouldn’t you rather keep half that money for yourself and deck out your spare bedroom? OK, maybe not. When this Covid-19 thing is over, cinema will still have a place in our culture, in spite of the fact that we could just as easily watch a movie at home.

But there are other innovations that might just change things. One of Clarke’s favourites was the hologram. When Luke Skywalker first sets eyes on Leia, she’s little more than a projection from R2-D2’s hard drive, although that in itself is enough to get him going. Although holograms have been around for decades, real-time moving holograms are still some distance away. And yet, in time, a machine will exist that can conjure up an apparently living, breathing person right in front of you. As the technology progresses, holographic projection might become so real that the average person is unable to distinguish between a projected image and the real thing. If you reached out and tried to touch the person in front of you, your fingers would vanish into some ghostly apparition, but anything short of that and you will fail to distinguish between reality and a virtual presence.

Like a lot of scientific advances, people will be slow to see the hologram’s potential when it first arrives. But when it does, it’s hard to imagine how far we can take it. Will there still be a need for business-class air travel? Overnight, half the airliners in the world might suddenly have no purpose (if they even exist at all then). Certainly the current research into supersonic travel would prove completely fruitless given that the most likely passengers for such a project would be business travellers trying to minimise their time in transit. If that’s your intention, why transit at all? Might our bustling commuter trains suddenly start to feel empty?

But before we even think about our careers, most of us are engrossed in our education. In the context of the British educational debate, the focus often returns to the issue of privilege. Most of the arguments are about access – in particular, who gets access to specific courses and institutions. For your average kid in the street, it is practically impossible to access an elite institution like Harvard or Oxford. More than that, even if we shunt the current batch of students to one side and replace them with another, all we have done is deny that same privilege to one group in order to give it to another.

I’ve never met an Oxford graduate that didn’t have some sort of edge to them. Even if they seem ordinary when you first meet them

In the future, this could change – and sooner than you might think, if virtual teaching in the coming months isn’t a disaster. Supposing we were able to film every lecture and every tutorial at Harvard and Oxford and make them available online. What reason would anybody have to feel excluded? If we can conjure up a life-sized 3D image of one of the most famous maths professors in the world, in any lecture theatre in the world, how then could it be claimed that anyone has been left out?

Every so often there’s an outcry because a kid in the middle of Africa has been refused an educational visa to Britain or America. Once virtual reality exceeds a certain point, will such a claim still have any meaning? Supposing we set up an identical lecture theatre in a number of countries – right down to the wooden furniture and the oak-panelled reception rooms. Even in countries that quite obviously can’t afford to fund the full spectrum of courses, every course will be available. Doubtless this kind of technology will come, and it will be a game-changer. This kind of thing even has relevance to the immigration debate. Do we really need to house several hundred thousand foreign students in Britain, cluttering up our already crowded housing stock and infrastructure?

A short while ago, I visited Sheffield (the place where I was born) and found it much changed. One of my old friends from Imperial has bagged himself a lectureship there, and I asked him if he thought the teaching in his university really warranted such attention from the Chinese middle class. In short – he told me – no, it doesn’t, but what the students are paying for is much more than an academic education. They are paying for a lifestyle experience, an opportunity to immerse themselves in the English language and to experience a culture very different from their own. The actual lectures are only a part of it.

There’s a lot more to the university experience than just that. Projecting lectures all across the planet enables you to deliver only one part of the university experience. Science courses involve lab work that isn’t easy to simulate without the physical presence of a tutor and real equipment. And in part, the very nature of a university course is to isolate yourself from the rest of the planet and indulge in a very narrow range of friends with a common interest. A science graduate I know from Oxford has always told me that she learnt more from her friends in the pub than she did from the actual lectures. Trying to motivate yourself to keep studying is in part an issue of herd panic. If you aren’t surrounded by other people who are interested in the same thing, it’s harder to maintain your own interest. Being dragged away from the family nest in your late teens can be daunting, but at least it initiates the process of independent living.

A virtual elite education of the kind I’m suggesting might save billions, but it would only work for highly motivated individualists

When you claim to have obtained a qualification from this or that university, what your potential employers are looking at is a brand label. I’ve never met an Oxford graduate that didn’t have some sort of edge to them. Even if they seem ordinary when you first meet them, they’ll suddenly come out with something different once you get to know them – something that a more ordinary university graduate simply wouldn’t even think to say. For this reason and others, I often become very apprehensive when I hear people talk about trying to reform our elite institutions, to change the priorities of intake and to introduce the forces of social engineering into our education system. One of the few things that Britain still does very well is elite education, and there’s a steady stream of product coming off the production line every summer. Why would you want to change that?

Before you even think about going to university, you might have an interest in secondary-school education. In a quiet, politically incorrect instant of self-pity, you may have felt distressed that you never went to Cheltenham Ladies’ College or Eton. Unlike Prince William and Prince Harry, you never had private tutorials from the next independent candidate for London mayor who answers to the name of Rory. If this sort of thing has been bothering you for years, don’t worry. Pretty soon, that will all become a thing of the past. Or at least I’ve always thought so.

It’s now technologically possible to film just about every A-level course on offer at most of the leading private schools and project that course into every sixth former’s home. Supposing you’re trying to sit A-level physics and you’ve just decided that your physics teacher is crap, and that the building you visit each day, which society has labelled a school, is just a building in a field where a bunch of kids are herded in and out according to a rigid timetable. Well, worry no more. We can tap you into the online Winchester course in physics at a moment’s notice. Soon there will be no need to deny anybody anywhere the very best of what our society can offer – right?

Maybe. A lot of people who tout specific educational policy don’t actually have a lot of interest in whether or not it will work. Very often it’s about ideological exhibitionism. As a kid, I got a huge amount from books that I borrowed from the library and educational TV shows I watched on the box. Even then, there was a simple television screen in every home, albeit one with only four channels. But whereas a private education was only available to 7 per cent of kids, the TV that we broadcast into virtually every home was always the same, and even this great leveller didn’t seem to do that much to level educational attainment. Again, the simple matter of a voice and a face speaking to you isn’t quite the same as a teacher.

Teenagers in particular are fantastically susceptible to peer pressure and they usually grow up to resemble the people around them. Just watching a bunch of toffs speak very politely about Aristotle wouldn’t necessarily change you into one, and it takes years to assemble the body language and the speech patterns of the British elite. A virtual elite education of the kind I’m suggesting might save billions, but it would only work for highly motivated individualists who could nurture themselves without peer pressure or the mentorial benefit of that thing we used to call a teacher.

Watch this space. It will certainly be an interesting experiment to perform.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments