How is coronavirus changing British politics?

Just eight months on from the election, the political landscape is set to change again, thanks to Covid-19 – not only ending the Brexit interlude but bringing about a return to left and right politics, writes Mark Leonard

Brexit, and the populist tide that swept Boris Johnson into Downing Street with an 80-seat majority last December, were game-changing moments in British politics. In both cases, commentators suggested that we were entering a new era in which voters would jettison traditional red and blue allegiances, and be primarily motivated by questions of identity, which would trump economics. Like the US, it seemed culture wars would now be a feature of British elections. This analysis was confirmed by the scale of Johnson’s win, in which voters on average incomes, who had been battered by a decade of austerity and fiscal restraint, still lent their vote to the Conservatives in large numbers to “get Brexit done”.

Yet, just eight months on from the Conservatives’ landslide, the political landscape is set to change, again, as a consequence of Covid-19. The Brexit divisions, which the Conservative Party harnessed to varying degrees of success in 2017 and 2019, appear to be falling away as vote mobilisers. The government’s coalition of a mixed left and right base – which unite around Brexit – could be less a tectonic shift in British politics, and more a historical oddity that lasted for four feverish and exhausting years between the referendum and the passing of the EU withdrawal bill.

Now the Brexit smoke has cleared, we seem to be back in the pre-2016 landscape where voters judge governments according to their competence on domestic issues. The Conservatives think they have hit a winning electoral formula by combining a bellicose tone abroad with a left-wing Keynesian economic model at home. Such a combination, it was hoped, would appeal to the hearts of those “red wall” Labour voters who have defected, as well as their wallets. However, the Conservatives are in danger of underestimating the voter appetite for a more outward-looking and global UK.

These are just a few of the takeaways from a new poll of Britons, published this week by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). In a sample of 2,000 voters, we found that far from exacerbating existing divisions, the coronavirus crisis could bring about the return of “left and right” politics and an end to the UK’s four-year Brexit parenthesis.

In this new world, the appeal and opportunities for the Conservatives and Labour have shifted and point to a more competitive battleground in the next four years. For instance, with the Conservatives, our polling found no evidence of any lasting “rally around the flag” support, which, earlier in the year, had catapulted them to 55 per cent in the polls. For Labour, our UK dataset shows a slow, but developing, uptick of support under Sir Keir Starmer, as well as some more marginal gains for other opposition parties. Perhaps most significantly, though, it reveals that Britons are becoming increasingly cross-pressured by currents events and, in turn, exiting the new political tribes they joined following the 2016 Brexit vote.

This unique snapshot of public opinion suggests that, less than a year into a majority Conservative government, the political landscape is far from assured. It reveals the impact that Covid-19 is having on Britons and their view of their world, and, more worryingly for Number 10, a shift away from, or rejection of, the prime minister and his party’s handling of the crisis.

In our survey, which presented respondents with nine options about who was most to blame for the loss of British lives, the single largest answer was the “UK government”. It also found that broader public opinion of the government has worsened significantly through the course of the pandemic – with over half of Britons (54 per cent) now holding a negative view of Johnson’s government. Even among Conservative voters, we found that almost a third (32 per cent) believed it had performed inadequately.

Admittedly, with a crisis as unique as Covid-19, the challenge is considerable for governments the world over. However, here in the UK, the effects are complicated by the clustering of voters on either side of the Brexit debate since 2016.

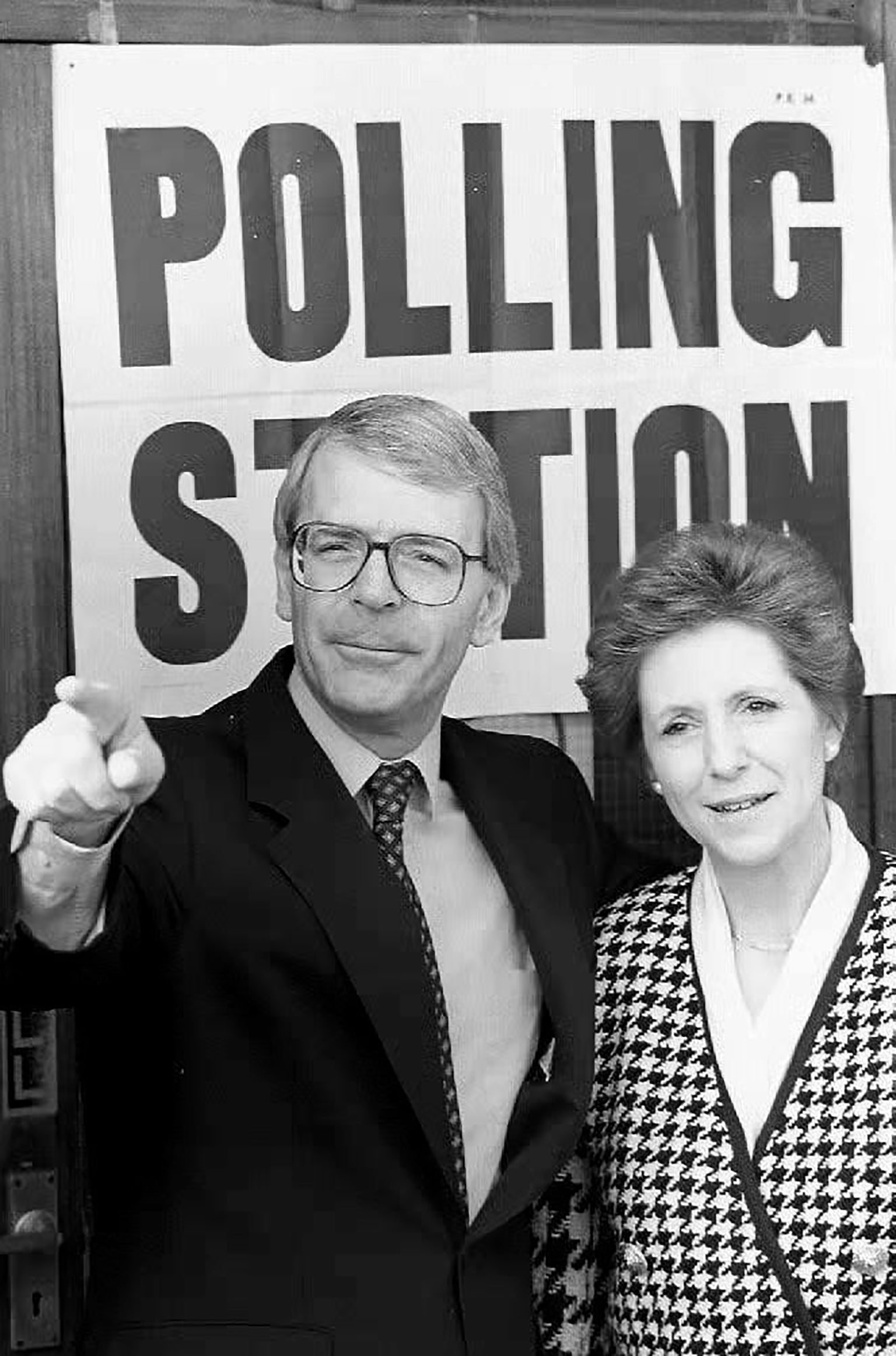

In this volatile environment, Johnson’s management of the crisis risks becoming his version of John Major’s “Black Wednesday” turning point of 1992 – an event that so totally transforms perceptions, that it could open up the way for a political realignment.

Our polling suggests that Covid-19 could have such an effect, by pushing new issues to the fore, and by cutting the roots of the tribes that grew around Brexit. In our dataset, we found an emerging sense of commonality between the hitherto distinct Leave and Remain voter groups. While many still have different attitudes towards political parties – with Leavers more sympathetic to Johnson and more likely to blame China for the outbreak and impact of the coronavirus, and Remainers generally aligned with Labour’s Starmer and critical of the government’s response – we noticed majorities in both camps for a centre-left economic agenda, of higher government spending and wage rises for the lowest paid, as well as for a more outward-looking UK in response to crisis. If such a pattern continues, Brexit, as a vote driver, is likely to carry less appeal in the coming election cycle.

Interestingly, and perhaps most emblematic of the current blurring of the UK’s Brexit identities, is the way that the two sides are now thinking about freedom of movement – an issue that was a clear dividing line between the groups for the past four years – and internationalism. In our poll, we found that 66 per cent of Britons agreed that Covid-19 shows that there is a need for more international cooperation, while only 18 per cent said it showed globalisation has gone too far. Considering that the excesses of globalisation were widely blamed for the Brexit vote, and became a toxic term among parts of the left and the right, this is a remarkably low figure.

In our efforts to drill further into this, and identify other areas of commonality, we constructed a “ladder of internationalism” to unpack in what areas people are willing to work together. Unsurprisingly, at the height of the crisis, we found that 86 per cent of Britons wanted to see more international collaboration for the development of a vaccine. Almost 70 per cent of respondents were also in favour of working with EU member states to localise the production of medical supplies, while there were majorities on working with other countries' governments to fill skills gaps (55 per cent), managing borders for tourism (60 per cent) and even sharing the economic burden of the crisis (54 per cent). There is also some commonality on climate change. This is unusual, in a comparative sense, given the loss of momentum for action on green issues following the last downturn in 2008. Yet, this time, we see its support holding up, with 62 per cent of Britons indicating that they want stronger government action on climate change post-Covid, and just 9 per cent disagreeing. When we asked respondents a three-part question on this subject, we found that 55 per cent agree that “climate is like the pandemic and that we need to take action now” – a response that significantly trumps “it is nowhere near as urgent” (at 24 per cent) and “climate is not a real problem” (at 6 per cent).

This issue, which transcends borders, also now extends to general attitudes to the UK’s place in the world – or what the government has long dubbed, a “Global Britain”, post-Brexit. Before the pandemic, many voters, particularly on the Leave side, believed that the UK would make common cause with the Anglosphere – US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand – and develop an enhanced transatlantic relationship as a substitute EU membership. However, as our data shows, public attitudes towards the US have fallen off a cliff during the pandemic, with two-thirds of Britons (66 per cent) indicating to us – including majorities across Labour (80 per cent), Conservative (61 per cent) and Brexit Party (58 per cent) voting groups – that they now hold a “worse” view of the UK’s transatlantic partner.

Attitudes towards China are no better, either, with over half (56 per cent) of our respondents indicating that their opinion of the country has worsened during the crisis. Only 1 per cent of Conservatives say their perception of China has improved, and just 7 per cent of Labour supporters agree. There is, therefore, a stark contrast between British voters’ desire for greater international cooperation and their negative perceptions of some of the biggest international players.

At last December’s election, Johnson, to the benefit of the Conservatives, spoke to many of these voters and the "somewhere" values of those whose connections, work and lives were rooted in their local community. This contrasted with the “anywheres”, the fleet-of-foot children of globalisation – generally more affluent, often younger, and more Europhile – who happily work, live and connect with friends across national borders.

It allowed him to capture voters whose position on traditional issues, such as the economy, were more allied with Labour, but who, culturally, strongly distrusted the European Union. This strategy was so successful that the party established a 15-point lead among low-income voters, according to one pollster, and developed a base that was more “working” than “middle” in its class identity. To keep hold of this new base, strategists in Number 10 devised a "levelling up" agenda, as a replacement to Brexit, and promised to pour investment into constituencies hitherto held by the Labour Party. It has not scrimped in this pursuit yet either, despite the outbreak of the coronavirus.

However, as ECFR’s polling shows, Covid-19 could yet exacerbate the gap between Conservative MPs and the electorate when it comes to fundamental issues, such as public spending. As our data reveals, the health crisis has prompted a leftwards shift on economics, and a growing appetite for progressive, redistributive agenda. We found, for example, that just under half of the respondents to our survey support higher government spending, including 44 per cent of Conservative voters. At 79 per cent, there was also overwhelming support for significantly increasing wages for NHS nurses and care workers, with 71 per cent of Conservative voters indicating their support for this measure (92 per cent among Labour voters). While on raising the wages of other key workers, such as supermarket employees and refuse collectors, we detected support from around three-quarters of the electorate across the UK (the breakdown was 61 per cent and 90 per cent among Conservative and Labour bases respectively). Just over two-thirds of all voters – including 53 per cent of Conservatives and 85 per cent of Labour supporters – said they want an immediate increase in the national minimum wage from its current level of £8.71 to £10.50 an hour.

For many Conservatives, this pivot to the left will be deeply uncomfortable, and does not marry with their historic pitch for “responsible, budgeted spending”. The forthcoming spending review this autumn could therefore prove transformative for the party and its brand, as it seeks to hold together groups that, in normal times, would be ideologically incompatible. Its approach to matters of structural inequality is also likely to raise some eyebrows among parliamentarians and its grassroots, particularly if it continues its recent pattern of state intervention.

According to our data, the Conservatives could be squeezed on this point, whichever route they take. For example, we found that just 5 per cent of UK respondents think that spending cuts represent the best means of paying for wage increases of key workers. The highest scoring responses in our survey were “cracking down on tax avoidance” (at 72 per cent); a 50 per cent income tax rate on individuals earning more than £200,000 (57 per cent); a mansion tax (47 per cent); and a levy on multinationals (42 per cent). These are avenues that would be deeply unpopular among the free market and libertarian wings of the party.

For Labour, such a split presents opportunity. It also vindicates much of their economic pitch from the 2017 and 2019 elections. Under a more electable leader, in Starmer, our polling shows that the party is already making headway in attracting voters back to its brand – with a quarter of new supporters coming from the Liberal Democrats, and around one in five (21 per cent) from the Conservatives. Meanwhile, 43 per cent of the SNP’s 2019 constituency also told us that that they would be receptive to voting Labour at the next election.

Yet, crucial to both of the lead parties will be the red wall defectors, who backed Labour in 2017 but went “blue” in 2019 – and who make up the seats in its former heartlands in the Midlands, the north, and Wales. They comprise just 6 per cent of the population but are heavily overrepresented in marginal constituencies that will decide the outcome of the next election. Almost a quarter (23 per cent) of the red wall defectors currently intend to vote Labour, according to our data, while the Conservatives are set to keep just 21 per cent of their 2019 constituency. More broadly, we found that the Conservative lead over Labour is down from its March and April highs across these seats, and there is evidence that Labour’s messaging, and its new leader, is having an impact to benefit of the party.

Ultimately, the killer question in these seats, and other marginals across the UK, will be whether the established divide between Leavers and Remainers will fade, or disappear completely, by 2024. Our data suggests that voters are becoming more receptive to broader political pitches, but it is still unclear whether new identities will form and how these might connect to parties. The idea that Covid-19 will be a game-changer – like the 2016 Brexit vote – is strong, and a realignment of some sort is almost certain. This presents opportunities for parties to recalibrate their offer, or to frame certain issues differently, in an effort to broaden their appeal. The shock of the pandemic has brought fundamental questions of competence to the fore. There now appears to be greater support among the British public for a redistributive agenda, as key voting groups such as the red wall defectors find themselves in economic distress. And, importantly, rather than supporting isolationism, these important groups also express support for a pragmatic internationalist agenda. Taken together, a new era of political competition may be beginning – and marking the end of the Brexit parenthesis.

Mark Leonard is the founding director of the European Council on Foreign Relations and the author of ‘The Brexit Parenthesis’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks