Unlike Europe, Britain failed its victims of the contaminated blood scandal

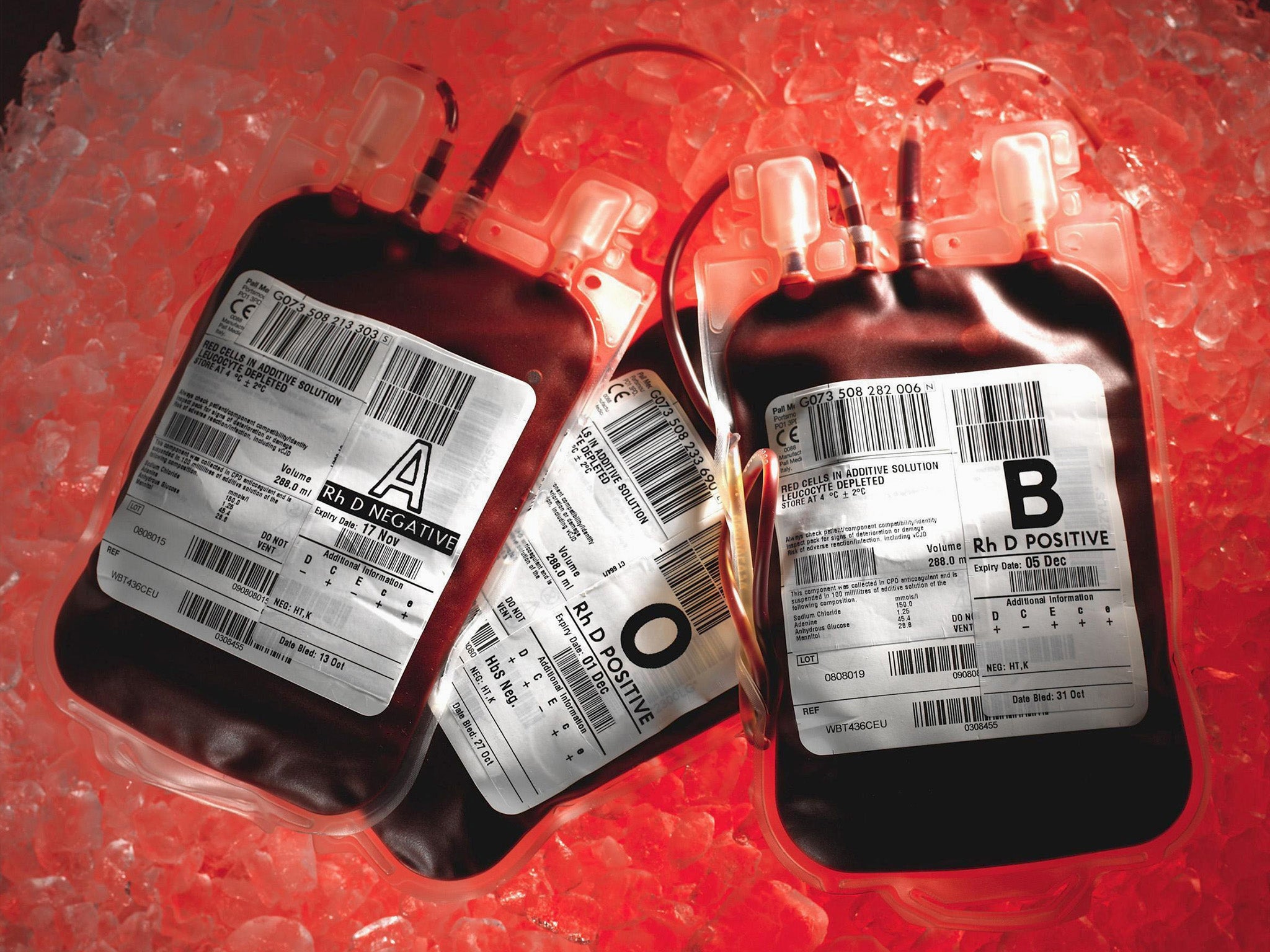

More than 2,000 people died after contracting HIV and Hepatitis C from tainted blood transfusions under the NHS. Yet this scandal never prompted the public or media outcry it deserved. It was a different story in Europe, writes Mary Dejevsky

How the government responded to the coronavirus pandemic is bound to be the subject of a mammoth inquiry, probably multiple inquiries, in the years to come. In some ways, the inquest has already started, as all those involved – from ministers to the NHS via the Civil Service, scientists and commercial companies – try to shelter themselves from the gathering storm.

But it is not the first time that the UK has had to face the fall-out from a major health emergency. Those of a certain age will recall the outbreak of BSE, popularly called Mad Cow Disease, when more than 4 million cattle were slaughtered and the then Agriculture Minister, John Gummer, now Lord Deben, notoriously fed his small daughter a hamburger to demonstrate the supposedly unimpeachable excellence of British beef.

This was in 1990, six years before the UK admitted that BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) could indeed be caused by eating meat from infected cattle. A nationwide panic about meat-eating ensued; many international markets were barred to British beef, and there was a big row about farming practices – how could there not be? – with the French. In the end, it was the farmers, rather than the scientists or poor regulation or commercial pressures that mainly took the rap.

The long-running BSE debacle, however, partly overlapped with a far bigger public health disaster, which combined many of the conflicting interests so familiar from today, while remaining largely out of public view. This was what is now known as the infected blood scandal, when haemophiliacs treated with the blood-clotting protein, Factor VIII, and people who underwent blood transfusions for whatever reasons, contracted HIV and Hepatitis C from contaminated blood.

Payments are still not fully standardised, varying from around £18,000 to around £45,000 a year, and are paid separately by the UK’s devolved governments. Over 30 years, individuals had lost their livelihoods; families their breadwinner; parents their children, yet the state has essentially turned away. At best, governments treated the issue as closed by the 1991 settlement; at worst, they acted as though it had never happened, lest the knowledge harm trust in the NHS.

Extraordinary though it may seem for a medical catastrophe that affected so many people, it is only now that a full public inquiry is in train.

There were, it is true, two more limited inquiries in the interim. As Scotland’s health secretary in 2008, Nicola Sturgeon called an inquiry chaired by Lord Penrose. But its findings, published seven years later, were widely dismissed as “a whitewash” and its conclusions boiled down to the recommendation that anyone who had had a transfusion before 1991 should – in today’s parlance – “get a test”. No blame was assigned.

And the year before Scotland’s inquiry opened, a former Solicitor-General for England and Wales, Lord Archer, and the former UK Health Secretary, David (now Lord) Owen, joined forces to try to get to the bottom of what Owen described as “a horrific human tragedy”. The result was an independent inquiry, funded largely by voluntary contributions. But it had no official status and no power to subpoena witnesses or demand sight of documents. No government officials appeared.

The 2009 Archer Report expressed “dismay” at what it found to be the lackadaisical approach of the authorities to the dangers of infected blood and called for equitable compensation. But there was no government action, and no one was held to account.

It was not until 2017 that the political and judicial climate seemed to shift. This could have been in part because Britons and their lawyers had by now acquired a taste for American-style litigation and survivors of the tainted blood scandal saw the sort of settlements others were winning for medical mistakes. It could also have been, however, that when a campaign group made the first moves towards taking the government to court, ministers saw an inquiry as a preferable, and delaying, alternative. Then again, perhaps something in the victims’ accounts down the years had touched the then prime minister, Theresa May.

For whatever reason, it was announced that there would, after so many years, be a full UK-wide public inquiry. The result is the Infected Blood Inquiry, chaired by Sir Brian Langstaff QC, which opened just over two years ago. You can get a harrowing impression of the suffering, the anguish, and the anger of the families affected by watching the video of the individual testimonies included in the opening Commemoration.

Actual witness evidence was heard from April 2019 in sessions held around the country. Again, in an exemplary display of openness, all the sessions, which include these often affecting exchanges, can be viewed on the inquiry website: https://www.infectedbloodinquiry.org.uk/

Now, more than two years in, and with at least another year to go, the inquiry is hearing evidence from medical and scientific experts, some in person and some – because of the Covid restrictions - virtually. And it is no small irony that the inquiry is picking its way through the undergrowth of this past public health scandal just as the coronavirus pandemic is raising some of the same questions about scientific and political judgements, commercial interests and public health.

It is an irony, too – and one that will hardly be lost on the participants – that the dominance of the pandemic in the media and the public conversation has consigned this long-awaited inquiry to something of the same obscurity in which the tainted blood scandal itself languished for so long. Yet again, it seems, this devastating scandal is kept, though now unintentionally, under wraps.

Which is regrettable, not just because of the resonance it could have today but because, like the Coronavirus pandemic, this was a disaster with an international, as well as national, dimension, and the comparisons with how others dealt with the aftermath of something initially rooted in medical ignorance could have something to teach even now.

The difference between now and the 1980s, of course, is that as the pandemic has swept across continents, from Asia, through Europe to the Americas, social media and real-time information have allowed ordinary people to compare the response of their governments and health systems and reach their own judgements. This was not so with the spread of contaminated blood; it was a silent and largely secret menace that unfolded over more than a decade. But international comparisons are possible and, as with the Coronavirus pandemic, so far, the UK does not emerge with many laurels. Others, the Germans, the French, to an extent the Irish, did it better.

The whole sorry saga begins in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s in two ways. First, in the development and commercialisation of a blood clotting agent, Factor VIII, which was soon hailed as an almost miracle treatment for haemophilia because it enabled many sufferers to treat themselves at home and live almost normal lives. And, second, in the need of the UK and other European countries to import blood and blood products from the US because of a shortage at home.

The shortage reflected in part the demand for the new treatment. But it came about also because in most of Europe blood used in the health services came from voluntary donations and there simply was not enough. In the US, on the other hand, blood donations were – and still are – paid for and those selling their blood were at the bottom of the social pile, whose blood was more likely to be infected, either with hepatitis (later identified as Hepatitis C) or HIV.

That imported US blood could be tainted was noted as early as 1974 – and the risk was exposed in a campaigning UK documentary, Blood Money, filmed for Granada TV’s World in Action series and aired the following year. Admirably even-handed, Blood Money showed how Factor VIII, branded as Hemofil, had transformed the lives of haemophiliacs. But it also showed where the US blood came from and interviewed a Manchester hospital virologist who had observed “an unprecedented outbreak of hepatitis among haemophiliacs”, and deduced that they had been treated with contaminated blood.

The programme concluded by saying that the British government was asking the US Health Authority to re-examine its controls on plasma centres. It also said that the Department of Health was looking into “whether Britain was paying too much for imported concentrates”, price-gouging being another strand of the programme.

Heating the blood was found to be a solution. But heat-treated products were more expensive, and two interests coincided

This, it is worth emphasising when we consider international comparisons, was in 1975. And it is probably fair to say that the trade-off between the new treatment and the particular risks of importing US blood were probably not evident at the start. Indeed, Lord Archer remarked after his inquiry that UK ministers and health officials had not taken part “because there are things the government could have said in mitigation – things that weren't known about at that time".

Such plasma products were in their infancy and the scourge of HIV/Aids had not yet been recognised. It was only much later that Hepatitis C was identified – and the scientists responsible only received their Nobel Prize this year.

Nevertheless, the Manchester doctor and the TV documentary had sounded warnings that could have been followed up. Instead, blood products continued to be imported from the US without being tested before use in the UK. Through the rest of the 1970s and into the 1980s, hundreds of haemophiliacs and others who had blood transfusions came down with Aids, for which there was then neither treatment nor a test.

Heating the blood was found to be a solution. But heat-treated products were more expensive, and two interests coincided. The NHS, like other public health services, wanted to save money, and US companies wanted to offload surplus stock. By the late 1980s, most patients had been switched to heat-treated products only, but many had already been infected, while evidence heard at the UK public inquiry confirmed that the risk continued into 1991.

One key question for the inquiry is how soon the UK authorities knew about the risk from imported blood products; what they did about it, and when, and how far cost was an issue. Many of those infected were not told until many years afterwards, if at all. Some found out by chance from medical records they had not been allowed to see, and unknowingly passed the infection on to partners and children.

It later transpired that whole swathes of documentation from the late 1980s and early 1990s were missing, including the ministerial papers of Lord Owen – that rare creature, a doctor turned health secretary – who had been outspoken in talking of a cover-up.

While most European countries affected were slower to act than they should have been, some did much better than the UK. Germany and France took action earlier, in most cases a lot earlier, than the UK; more information about the scandal came into the public domain earlier; more blame was apportioned, and compensation settlements were agreed sooner and could be accessed with far less hassle than in the UK.

Germany, though far from perfect, offers a shining example of what could be done. Heat-treated blood products were approved for import in 1981, but made obligatory only after 1983. The delay, it was admitted, was because of short supplies and the expense. But that two-year delay was soon laid at the door of the authorities.

From 1982 onwards, the German authorities also recognised that there could be a risk of HIV being transmitted in blood and alerted doctors to the particular risk to haemophiliacs. Then again, there was an official silence and a delay, until 1985 when an edict came into effect, and HIV tests were introduced for blood donors.

In 1988, Germany’s infected haemophiliacs were offered compensatino out of court (three years before the UK settlement). In the following years, more details emerged that implied negligence among officials, doctors and pharmaceutical companies; there were hearings in the Bundestag. By 1993, the then health minister, Horst Seehofer, was taking a personal interest. He promised to ensure that damages were paid (they were); he abolished the Federal Public Health Office, sending its senior officials into early retirement, reportedly citing their negligence over HIV-infected blood. Several companies that had distributed tainted blood products were closed and their bosses sued.

The next year, a law was passed providing new monthly allowances for those affected. What was happening in the UK through the 1990s? Not much. Interestingly, Seehofer, who emerges as one of the heroes of the hour, rose through the CSU party and currently serves as interior minister in Angela Merkel’s government.

In France, the contaminated blood scandal first made serious headlines in 1991, after a medically qualified journalist, Anne-Marie Casteret, discovered that the national blood transfusion service had knowingly supplied HIV-contaminated blood to haemophiliacs in 1984-85. The service had postponed introducing a test, because that would have meant importing the equipment, and a French test was due to come on stream. In a subsequent book, Casteret also revealed that French scientists had been aware from 1983 that heat treatment neutralised the viruses, though insisted they had known only from 1985.

The French authorities – characteristically – took a judicial approach. Legal hearings chuntered on. But in 1992 three health officials were convicted of fraud for allowing contaminated blood to be given to haemophiliacs. The most senior received a four-year sentence, though he served only 30 months, and there was a widespread feeling at the time that politicians and more senior staff were being let off the hook.

Heating the blood was found to be a solution. But heat-treated products were more expensive, and two interests coincided

It took almost a decade from Casteret’s first revelations – and several failed indictments and hearings – but in 1999, the prime minister in the Socialist government at the time, Laurent Fabius, and two ministers were charged with manslaughter in connection with the scandal. Only the health minister, Edmond Hervé, was found guilty, though he was not sentenced. As well as – sort of – holding officials to account, France also introduced one of the earliest and more generous national compensation schemes.

If the blood scandal as it played out in Germany helped Horst Seehofer’s career, in France, one of the chief victims was Fabius. Once a political whizz-kid, widely fancied as a future president, he and his prospects were permanently damaged. He served in Lionel Jospin’s government from 2000-02, and as foreign minister during the presidency of Francois Hollande, but the political heights remained out of his reach.

In Ireland, political attention turned to the contaminated blood issue late, but not as late as in the UK, with the setting up of the Lindsay Tribunal in 1999. Its report, published in 2001, criticised the the National Haemophilia Centre for its slow response, and the delay before the blood transfusion service introduced heat-treated products. There were also claims of penny-pinching and a cover-up, but no one was held accountable.

Since 1995, however, Ireland has had one of the more generous compensation schemes, administered by a special tribunal. By 2019, it had paid out a total of €993 million, with some individual settlements exceeding €1m.

There are several common threads running through these accounts. Delay on the part of governments and health authorities in responding to evidence of infections from imported blood; a reluctance to order the use of purified products, in part for cost and supply reasons; and a tendency – shared by bureaucracies everywhere – to cover up uncomfortable facts. In acting on the information available, however, they were all well ahead of the UK.

Another common thread is how relatively little public indignation or even attention was shown, even when the truth started to come out. Everywhere, it seems, this has been something of a forgotten scandal. In most European countries, at least now, that may be because there has been a more or less thorough reckoning, backed up by compensation. That cannot be said of the UK.

As for why this scandal has been so neglected, the main reason may not be hard to find: the stigma of Aids, and to an extent Hepatitis C. This helps to explain why doctors were loth to tell their patients, and why patients tended to keep the bad news to themselves, often at great personal cost. Certainly, they were unlikely to go out campaigning. As one German sufferer said in a TV documentary much later: “In those days, who would willingly have gone out and, in effect, told the world they were stricken with a plague that supposedly infected only homosexuals, prostitutes and drug addicts?”

It is hard now to think back to those years. But some of those testifying at the UK inquiry have spoken of losing jobs, marriages and homes as a result of being infected with HIV, of having their front-doors daubed with insults and being treated as a social pariah. No wonder the campaign only really took off much later.

Another reason is that in a world before social media and no access to medical records, there was no way for people to compare their experiences or even to know how many shared their plight. The UK’s initial compensation system was classic divide and rule.

There is also the matter of accountability. The same tensions seen now between government, civil servants, and the various branches of the NHS over coronavirus were also at play during the infected blood scandal. Much information has gone “missing”, even though ministers swore it was all there (and then had to apologise for their mistake). The awe in which doctors were often held and their reluctance to impart information may also have been a factor. The internet has diminished that respect; patients are better informed and more demanding.

I doubt it would be possible to keep something like the contaminated blood scandal a secret now, and for so long. Even so, it is hard not to share the view of Jason Evans, a long-time campaigner whose father died from HIV/Aids.

Speaking in Marcus Plowright’s recent ITV documentary, In Cold Blood, he said this. “I think when you look at this in terms of the numbers, thousands infected, well over 1,500 dead, when you compare it to all the other national disasters – Hillsborough, the Birmingham bombings, Grenfell – the scandal that happened with the Factor VIII concentrates eclipses all of them combined. Yet it has never had that recognition.“

The central purpose of the UK’s grievously late public inquiry must surely be, finally, to put that right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments