Hull’s angel: Clive Sullivan, black pioneer in the social history of sport

Sullivan captained the last British team to win the Rugby League World Cup and scored a remarkable solo try in the final – but more significantly, he was the first ever black captain of any British international sports team. Mick O’Hare tells the remarkable story

If he’d played football, he’d probably be an OBE. If he’d played rugby union he’d almost certainly be a CBE. But he played rugby league, which is probably why he only mustered an MBE, the lowest rung on the honours ladder. It’s also worth pointing out that he was black. While Bobby Moore OBE and Martin Johnson CBE are rightly lauded as World Cup-winning captains of their nations, how many people have heard of Clive Sullivan? Perhaps they should have. Not only was he the captain of the last British team to win the Rugby League World Cup and scored a remarkable solo try in the final, even more significantly he was the first black captain of any Great Britain sports team, ever.

And while we have rightly been lauding the transformation of that once-solid adjunct to the apartheid regime, the South African rugby union team who won their World Cup in November led by their first ever black captain Siya Kolisi, Welshman Clive Sullivan became the captain of his national team a full 47 years earlier in what were, it’s fair to say, far less enlightened times.

This was back in 1972 – the first black footballer to play for the senior England team was Viv Anderson in 1978. But black players had been playing for the England rugby league team since the 1930s when the Cumberbatch brothers, Jimmy and Val, played against France and Wales. And the first black player to play for the full Great Britain team was another Welshman, Barrow’s Roy Francis in 1947, followed by Hunslet’s Cec Thompson in 1951. Meanwhile Alex Givvons had played rugby league for Wales in 1938, but it would be 48 years before a black player would represent Wales at rugby union, when Glenn Webbe played against Tonga in 1986.

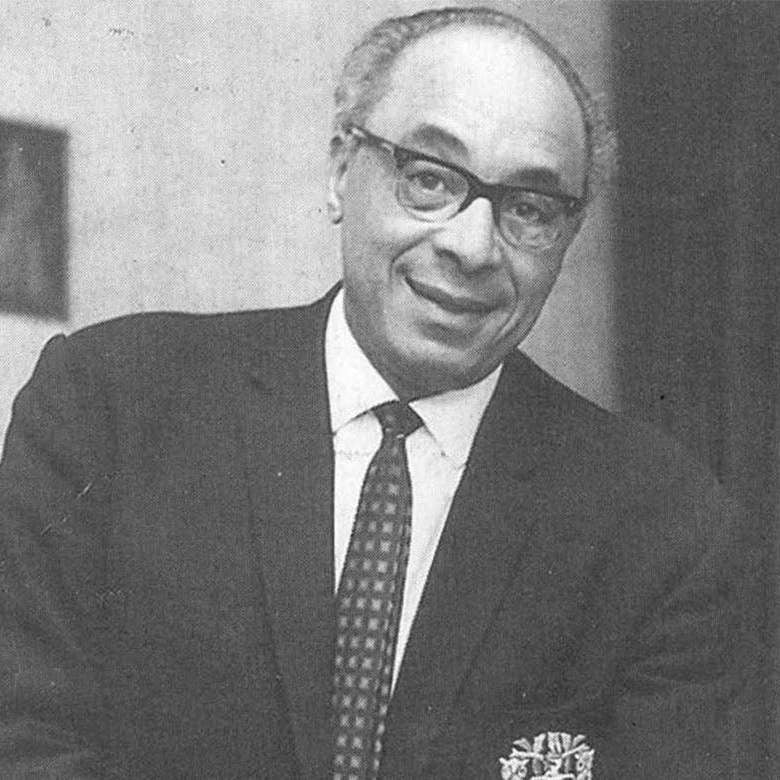

The man who coached Sullivan’s 1972 Word Cup-winning team was Jim Challinor. Both Alf Ramsey, who coached the England football team to their 1966 World Cup, and Clive Woodward, who coached England to their rugby union equivalent in 2003, were knighted. Challinor has no honour whatsoever, and he died aged 42 only four years after his triumph. When asked just before his death if he realised he’d made a significant statement in selecting a black captain of the national side, Challinor answered: “Actually I didn’t think twice about it. I just chose the best man for the job. The one the players would respect and be my representative on the field. It was the personal example he set. That’s all there was to it.”

When the England rugby union team won their World Cup in 2003 there was a triumphal parade through London. One can only imagine the reception if England won football’s World Cup again. But when Sullivan and his team won the Rugby League World Cup in 1972 nobody greeted them on arrival at Dover. In fact they were questioned by customs officers asking where they acquired the silverware they were carrying and whether duty should be paid on it. Then they got on the train back to their homes and workplaces, in Sullivan’s case to an aircraft factory in Brough, East Yorkshire.

Yet despite the less-than-glamorous background of life as a part-time rugby league player, Sullivan blazed a trail for the likes of Tessa Sanderson, John Conteh, Linford Christie and Cyrille Regis. It’s fair to say that even today Jessica Ennis, Mo Farah and Raheem Sterling are his long-term heirs. “Sullivan’s appointment [as captain] was extraordinary for the time,” Martin Polley, director of the International Centre for Sports History and Culture at De Montfort University in Leicester, told the BBC. “A few professional football teams had black players by this time, like Clyde Best at West Ham. But the England football team were six years away from even picking a black player for the senior team.”

Biographer James Oddy, author of True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, adds that he was a “pioneer in the social history of British sport. Clive did a lot for how society judged black athletes. One of his heroes was Muhammad Ali and perhaps that meant he was more aware than you might have thought about his role.”

Having been born in Wales, rugby union was the first team sport Sullivan played. But the Welsh Rugby Union had no intention of picking black players for its national team so, like Billy Boston, Colin Dixon and a host of other black Welsh rugby union players – one of whom was Danny Wilson, father of footballer Ryan Giggs – Sullivan switched to rugby league. Many of those players were from Cardiff’s Tiger Bay area – although Sullivan was born in nearby Splott to an Antiguan mum and a Jamaican dad – but now he was on his way to Hull on the opposite side of the country.

There is a stereotypical view of Hull. It is considered by a few sneering media sophisticates and social commentators as insular, Brexit-voting, and racially homogenous. But Sullivan proved it to be unfairly maligned. Not only did the city take him to heart but he did it even though he played for both the city’s rugby league teams Hull FC and Hull Kingston Rovers (“possibly the bravest single act any human can undertake”, according to the late Hull KR player Roger Millward) and was embraced on both sides of the city’s eponymous river. Sullivan first moved there at the start of the 1960s and became one of the city’s most famous sons, staying until his untimely death in 1985, and owning a social club and having a road named after him, possibly the greatest accolade modern Britain can bestow upon anybody.

Of course, it would be naive to say racism didn’t exist in rugby league, in Hull or anywhere in Britain at that time; of course it did. Just check out what passed for TV sitcom humour in that era. And shamefully, when the Great Britain rugby league team paused in South Africa on the way home from a tour of the southern hemisphere in 1962 to play exhibition matches in South Africa before the sport was outlawed there, black players in their squad carried on home to Britain. Even back in the unenlightened Sixties, famed BBC rugby league commentator Eddie Waring, a frequent champion of rugby league’s black players, denounced the decision as racist.

But rugby league was a sport built on the back of a monetary imperative. Once it began playing its players after splitting from the then amateur rugby union game in 1895, it suddenly needed to pull as many paying spectators through the turnstiles as possible. And that required having the best players on the pitch, irrespective of race or nationality. Thus began the practice of hiring great black players who otherwise would not succeed in rugby union – it was as much the politics of expediency as it was the politics of emancipation, although the former was instrumental in the latter.

And like Sullivan many of these players – from Givvons in the 1930s to Boston in the 1950s and Phil Ford in the 1980s – became star attractions on the pitch. Black South Africans who were barred from playing there (indeed, rugby league as a sport was eventually banned by the apartheid regime as a degenerate game) found acceptance in British rugby league and players such as David Barends and Green Vigo took the immense step of leaving their homeland to seek fame in the UK. Hull FC also led the way in appointing the first black coach of any professional sports team in Britain. Roy Francis took the position in 1956, mentoring the young Sullivan, before moving to Leeds in 1963 where he won the Challenge Cup. But again, although rugby league was in many ways enlightened compared to some of its sporting counterparts, Francis too was the subject of a reprehensible episode when, as a player, he was not selected to tour Australia in 1946 because that nation operated a colour bar.

Whatever, Sullivan rode above it all, his talent as a player showing perhaps better than words can that using skin colour to judge a human is risible. And change was on its way elsewhere, Sullivan played through the era of the US civil rights movement when Martin Luther King was able to declare that “I look to a day when people will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but the content of their character.” Jim Challinor’s remarks about Sullivan’s “personal example” seem apposite.

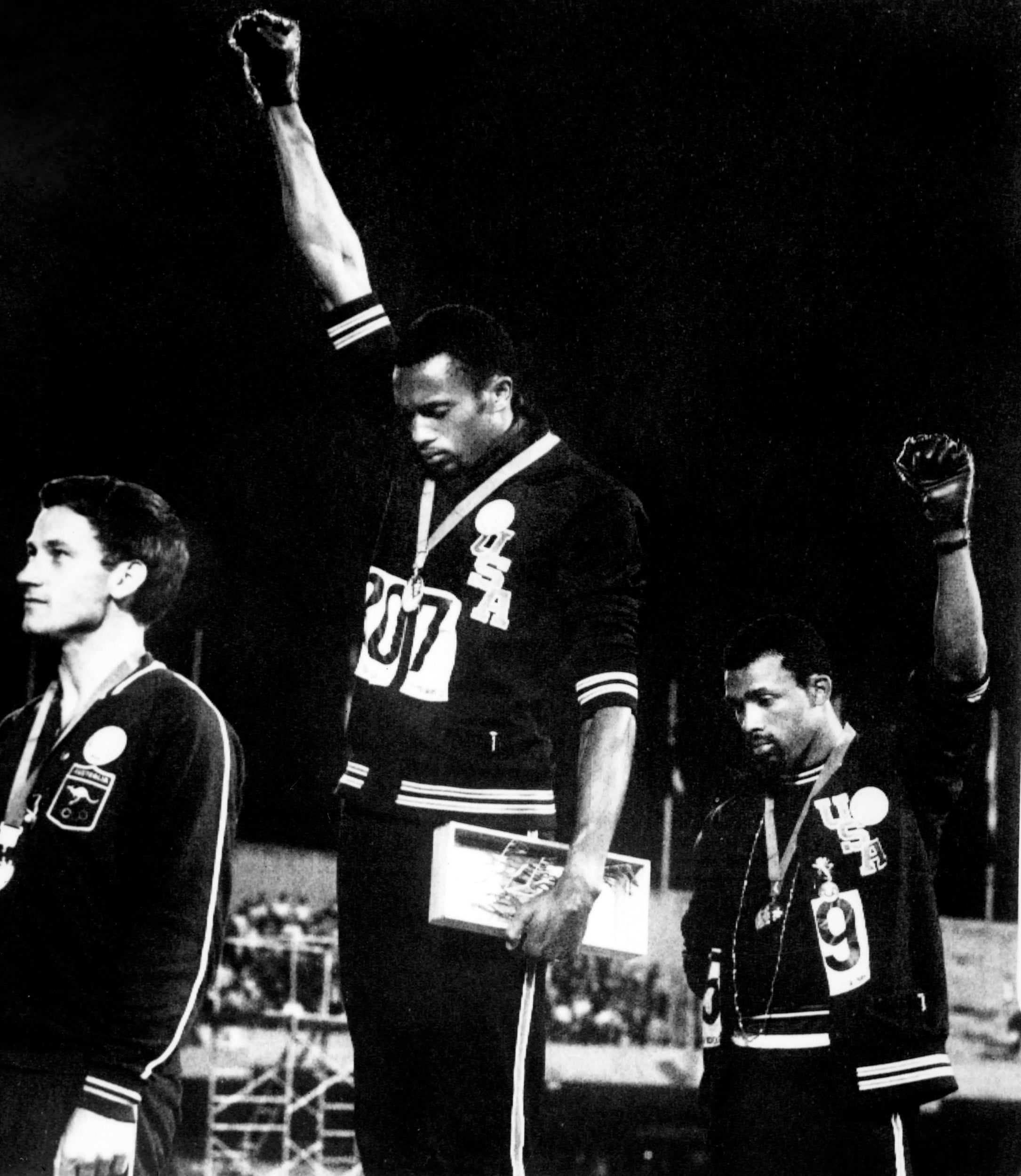

Black sportsmen were starting to make a stand too beyond the sporting arena. In 1968 US athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos made their “black power” salute during the Mexico Olympic 200 metres medal ceremony. That was the same year that Clive Sullivan would score three tries for Great Britain in his first World Cup campaign, the very year that Conservative politician Enoch Powell would make his divisive anti-immigrant “Rivers of blood” speech”, and an era when a Conservative politician in Birmingham ran successfully for office using the slogan “If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour”.

In the light of this, half a century hence, it seems utterly extraordinary that Sullivan was chosen to lead his country ahead of the other predominantly white European members of the squad. And while Sullivan himself said that although he did hear racist comments from the terraces it was a matter of “standing tall and showing your ability”.

Speaking in the early 1980s and before his son Anthony, who would also go on to play for Wales and Great Britain, began to make his mark, he said: “It wasn’t the mass racist chanting and vilification you’d hear at football. It was more them trying to put you off your game. If you spoke to them as one human to another human, maybe in the bar afterwards or before the match outside the ground, they would always back down. One-to-one they realise that the only difference is our skin colour, and you knew that they’d never make the same kind of comment from the terraces to you again.

“Of course, there will always be maybe a hardcore 5 per cent who will just intrinsically hate you whatever, but as a rule most people just wanted to put you off and because they’d never met you, you were dehumanised. But once you talked, they changed. I was never scared – I guess it helped being a rugby player – but never once at all the clubs I played for did I ever feel anything other than welcome in the changing room. And in the future, for people like Anthony growing up now, I think things will change.” Whether Clive Sullivan’s hopes have rung true only his son can judge.

Sullivan went on: “My proudest moment was scoring in the World Cup final in 1972. I still watch the try and the commentary of Eddie Waring shouting ‘Go, go, go, and he goes!’ and then being carried around the field on my teammates’ shoulders with the trophy. Sometimes I can’t believe it was me.” Eddie Waring’s commentary was rugby league’s “They think it’s all over moment” and, like the England football team, rugby league is still awaiting another.

And there’s more to Sullivan’s story. As an adolescent he had numerous operations on his knees and his doctors told him he might never walk again, let alone play rugby. He was almost killed in a car crash in October 1963, and throughout his career he would make many more visits to the operating theatre. But persistence paid off. He won the Rugby League Championship with Hull Kingston Rovers in 1979, following his move from Hull FC, and the next year he helped Hull KR to beat their local rivals to win the first and only all-Hull Challenge Cup final at Wembley. “Last one out, turn off the lights,” some wag had written on a sign by the motorway out of Hull as 95,000 people descended on Wembley.

Many will still say, only half-jokingly, that Sullivan’s greatest achievement was crossing a greater divide than the racial one: winning the respect of supporters on both sides of Hull’s rugby league rift. Mostly the few players who have dared to cross that particular Rubicon are accused of “treason” or “betrayal”, but when he died Clive Sullivan was mourned by fans on both sides. “He was a wonderful man. I never heard anyone say a bad word about him. I think everybody loved him…” says his former teammate David Doyle-Davidson. He was the only player to score a century of tries for both clubs. The winner of matches between the two Hull clubs now receives the Clive Sullivan Memorial Trophy.

His wife Rosalyn told the Africans in Yorkshire Project that “when Clive first moved to the north of England people would stare at him and want to touch his hair, including my own family. But in the end people just fell in love because he was such a decent man. My parents were at first taken aback that I’d started seeing a black man – we lived in a small village – but when they met him they were charmed too. The fact that we were a mixed race couple did not bother me whatsoever, but I soon learned that this was not acceptable to some people and could feel disapproval on walking into a restaurant or bar. I just hoped that eventually people’s opinions would change and I still have that hope.”

In his Gone North book, chronicling the lives of Welsh players who left their country to play professional rugby league in northern England, historian Robert Gate concludes: “Only two Welshmen have scored more tries than Clive Sullivan… for that reason alone he will always rank among the great finishers. None of the others, however, had faced so many obstacles in their quest for glory.”

And he was still playing in his fifth decade. Astonishingly, after retiring to concentrate on coaching back at Hull FC, he was unexpectedly called into their team for the 1982 Challenge Cup Final replay against Widnes, and won another winners’ medal only two years before he died prematurely of liver cancer. He had still been playing on and off for Doncaster only six months before his death. By then he had played 17 times for Great Britain, 15 times for Wales and scored 406 tries in his professional career, one of only nine players in history to top 400.

The Great Britain Rugby League Lions, after years of the home nations being split into their constituent parts, have only just been revived. On their recent tour to the Pacific they lost all four matches in quite dismal style, and lacked for a decent winger. And it’s now 48 years since Great Britain, or any home nation, last won the World Cup. The team now regularly contains black players, of course, and the next World Cup is scheduled for England in autumn 2021. But it still remains statistically likely that if a home nation wins, the cup will be lifted by a white player, which rather shows that, however far we may have come, Clive Sullivan’s achievement 47 years ago was all the more remarkable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments