Independent journalism has the power to fight fake news – we need it now more than ever

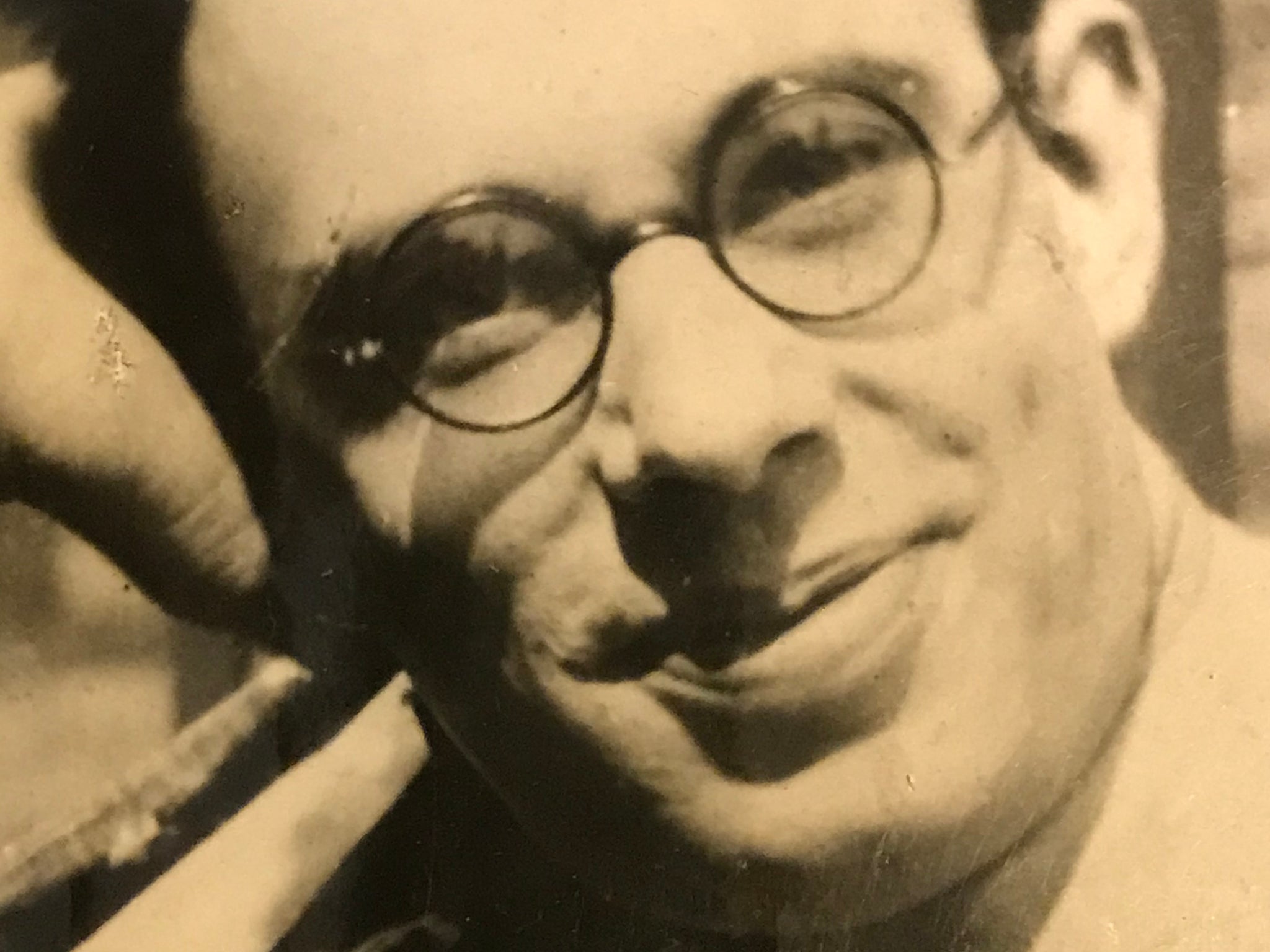

Radical journalist Claud Cockburn fought propagandists and fascists during the darkest hours of the 20th century. With the politics of the 2020s likely to be as toxic and unstable, his son, Patrick Cockburn, looks at how we can channel his spirit today

Governments like to persuade dissenting journalists that their efforts are too puny and marginal to influence or otherwise affect the powers that be. Yet there is no doubting the huge impact of the media on public opinion: Donald Trump would not be in the White House if he was not an expert in making sure that his words and actions top the news agenda every day. The departure of Britain from the EU would surely not have happened without most of the print press urging millions of readers for decades to blame Brussels for their troubles. But how far is it possible for individual journalists to resist and contradict this tidal wave of information and misinformation pumped out on a daily basis?

The aim of good journalism should be to tell the public what they need to know in order for them to reach informed decisions and to judge intelligently the performance of those in authority. But what if those same journalists conclude that the news propagated by the rest of the media is dangerously mistaken? Is there anything they can do about it, or should they throw up their hands in despair as many do, convinced that in opposing conventional wisdom, they will only be battering their heads against a series of brick walls without making a serious dent in it?

My father, Claud Cockburn, whose combative radicalism never weakened during his 60 years as a journalist and author, used to warn that governments deliberately promulgate gloom and despondency among critics of the status quo in order to demoralise them and persuade them to cease their supposedly ineffectual efforts. He was convinced that the powers that be, in the shape of governments and their media allies, were much more fragile than they pretended to be.

He argued that the saying that “battles are won by the big battalions” is propaganda put out by the big battalion commanders to persuade the leaders of smaller and weaker forces that they are hopelessly outmatched and should abandon the fight. He believed, on the contrary, that the wealthy and the powerful could be effectively harried and discredited by journalistic guerrilla warfare aimed at telling people what was really happening in the world.

As a young journalist, I found this view to be fine, morale-boosting stuff, and I always hoped that it was true, but I feared that it might contain a strong dash of wishful thinking. I could see that, all too often, those in power seemed to be coming out the winners.

Yet my father’s own career was strong evidence that the individual journalist, if he or she knew their business properly and their courage did not fail them, really could combat the forces of darkness. The balance of power between the big battalions – the politicians and publishers – and their under-resourced opponents was, so he said, not as unequal as might at first appear. As much as I would have liked this to be true, I was not wholly convinced of it until I obtained my father’s voluminous MI5 files and found that his pin-prick attacks on the establishment had created even more rage and dismay among his targets than he had hoped for.

At first Claud’s big idea seemed likely to founder. Circulation was ‘awfully steady at thirty-six’

Claud resigned his job as a correspondent for The Times in New York at the end of 1932 because he disapproved of its line on important issues – notably the rise of fascism and the Great Depression. Journalists threaten on occasion to resign from their media outlets as a matter of principle, but few actually do so, and his editors were disbelieving at first that he would cut short what promised to be a stellar career with The Times to strike out on his own.

He was indeed making a leap in the dark, but he did at least know in what direction he was leaping: his plan was to set up a radical newsletter filled with the sort of “insider” news that he saw being kept from the general public: “it was going to give the customers,” he was to recall many years later, “the sort of facts – political, diplomatic, financial – which were freely discussed in embassies and clubs but considered to be too adult to be left about for newspaper readers to get at them.”

His publication was called The Week (not to be confused with later publications of the same name), which he started with £40 borrowed from a friend, believing that there must be a pool of people as dissatisfied as he was with the partisan and self-censored information available in the rest of the press. He used the humble mimeograph machine, now a largely forgotten device, to publish cheaply and so level the playing field between himself and those with vastly greater resources, just as 60 years later the invention of the internet was to democratise the distribution of news and opinion – along with lies and propaganda.

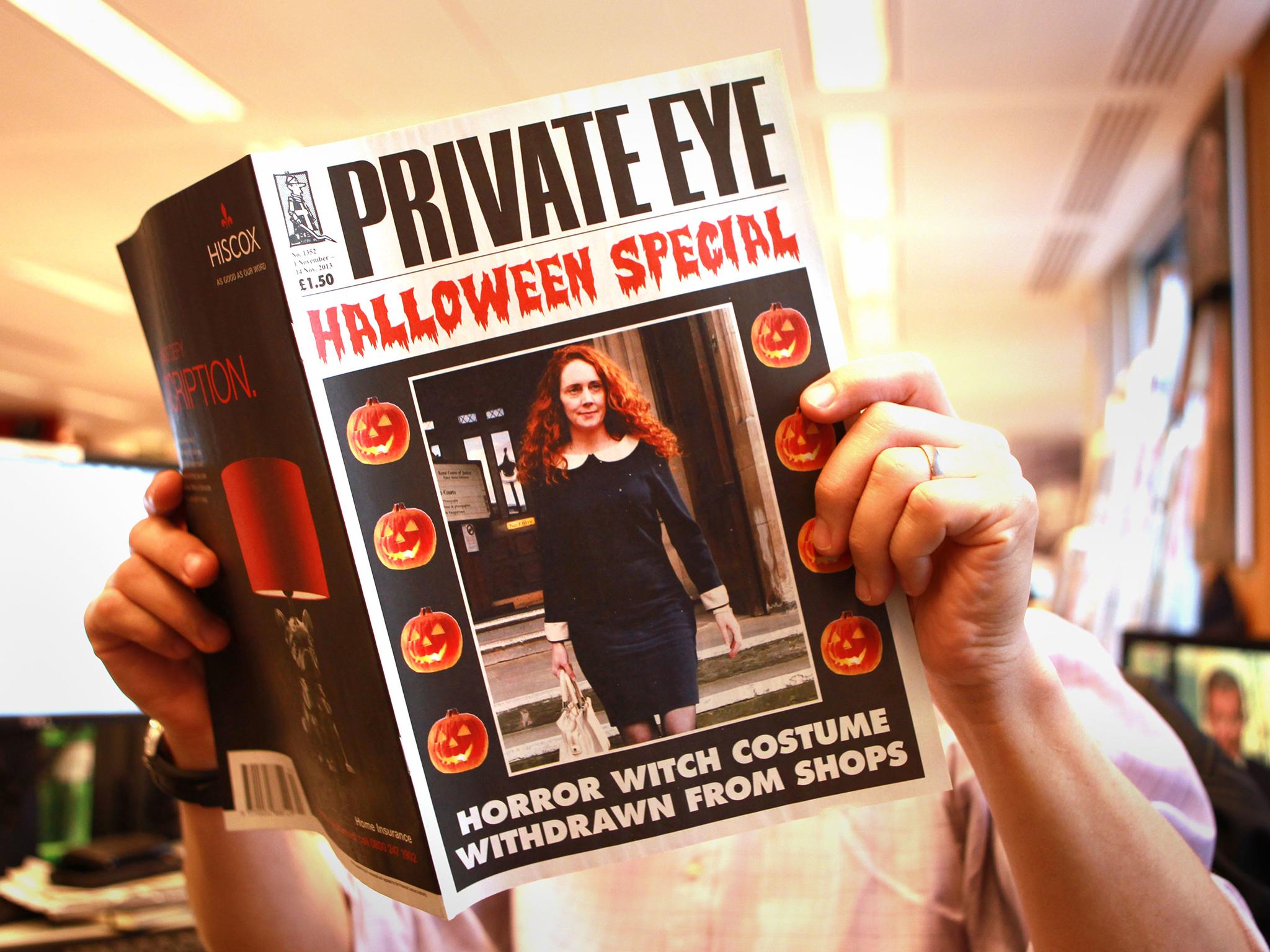

From its first issue, The Week gave a sense of telling the reader about the hidden machinations and motives of those in power as it exposed and denounced them, its approach and style strongly resembling that adopted by Private Eye when it started up in 1961.

There are investigations by MI5 into every aspect of Claud’s life: surveillance of his movements, interception of letters, interviews with colleagues

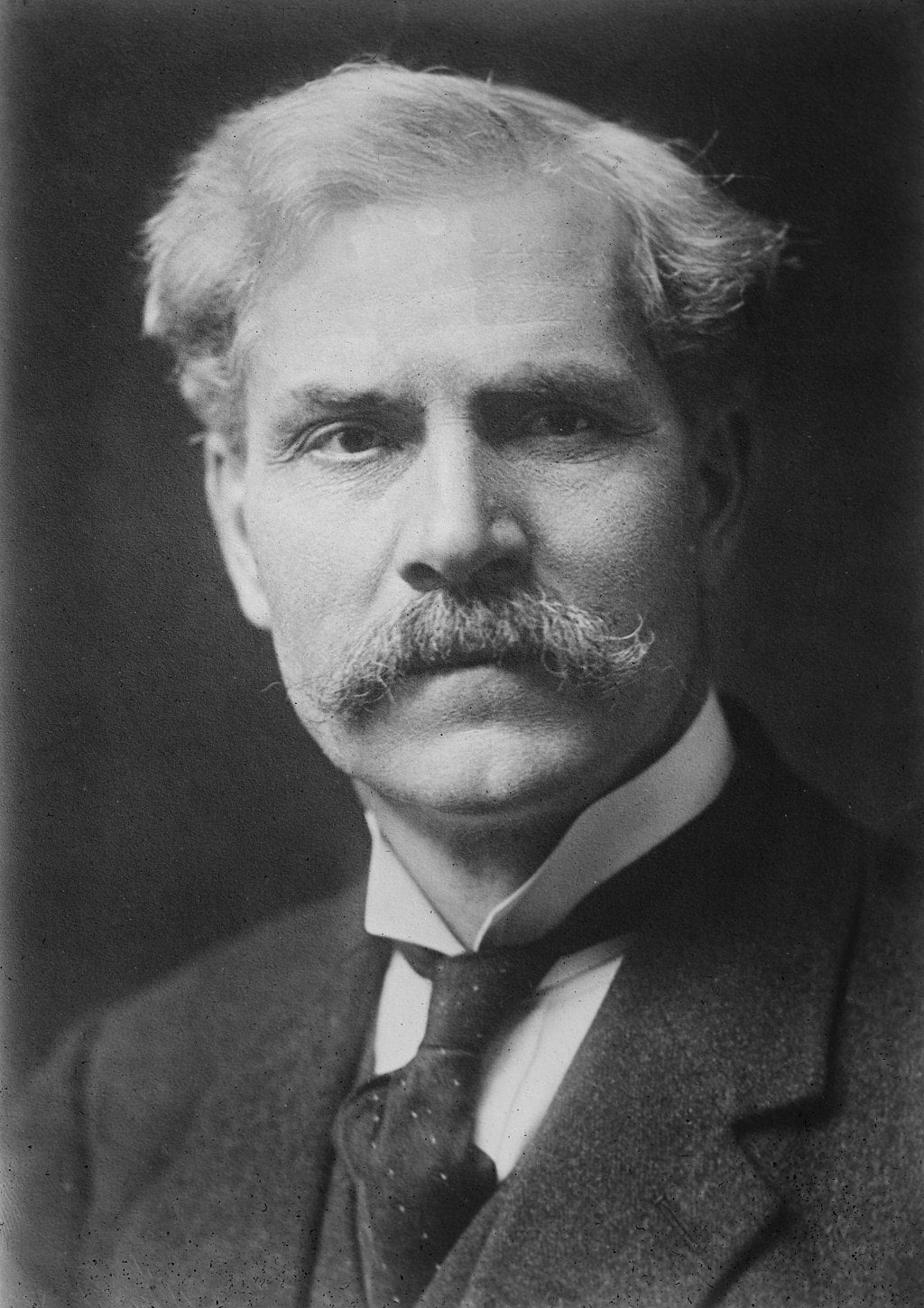

At first Claud’s big idea seemed likely to founder. After the first few issues, he found that the circulation was “awfully steady at thirty-six”. It showed a high degree of self-confidence on his part that he stuck with his conviction that, with economies and governments collapsing on every side and Hitler coming to power in Germany, there must be a vacuum of information that intelligent people would want to see filled. In the event, his project was unintentionally rescued by Ramsay MacDonald, the British prime minister, who was so enraged by a piece in The Week deriding an economic conference in London, which was his favourite child and over which he was presiding, that he summoned a press conference. Holding up a copy of the offending newsletter, MacDonald denounced it and warned journalists to ignore its false prophecies. My father’s description of the scene is worth quoting as an example of his literary style: “As a warning utterer he [MacDonald] was really tip-top,” he wrote. “In his unique style, suggestive of soup being brewed on a soggy Sunday evening in the West Highlands, he said that what we saw on every side was plotting and conspiracy … and here in his hand was a case in point.”

The Week never looked back, swiftly becoming one of the most quoted papers in Britain, its reputation and circulation propelled by scoops on everything from the abdication crisis to revelations about the clique of appeasers known as the Cliveden Set. Claud made a virtue of the absence of financial backing (nobody was likely sue him since, whatever a court decided, the complainant was not going to get any money). He rebuffed well-meant offers of help from journalists and would-be journalists: “I had to keep firmly in mind that what we were running was a pirate craft and we could not burden ourselves with conventional navigators and mates, however skilled and knowledgeable.”

Claud rebuffed well-meant offers of help from journalists and would-be journalists: 'I had to keep firmly in mind that what we were running was a pirate craft'

I wanted to find out if my father’s natural pride in the success of The Week had led him to exaggerate its real impact, but I could not see a way to do this. Then, in 2003, on the advice of a friend experienced in researching the archives of European intelligence services, I wrote to the director of MI5 asking for Claud Cockburn’s file to be released to the National Archives at Kew. I received no reply, as I had been warned would be the case, but a year later 26 bulging buff-coloured files were deposited at Kew, covering Claud’s activities between 1920 and 1953. As I read through them, I felt a growing regret that my father could not see the files – he had died in 1981 at the age of 77 – as the anguish his journalistic activities had caused to officials and politicians became apparent.

The first document in the file was from a British military intelligence officer in the occupied Rhineland in 1924, who reported on an unauthorised visit by two young men: Claud, then 20 years of age, and Graham Greene, both students at Oxford and both former pupils of Berkhamsted School where Greene’s father was headmaster. The intelligence officer noted suspiciously that “both men appear to be authors”.

Some letter writers denounced Claud as a Comintern superagent. Government officials demanded that he be prosecuted, detained and generally put a stop to

The rest of the MI5 papers post-date the start of The Week in 1933 and are of two kinds. Firstly, there are detailed investigations by MI5 officers into every aspect of Claud’s life: surveillance of his movements, interception and monitoring of letters and phone calls, interviews with colleagues past and present. Much of the information so laboriously gathered was accurate and interesting, though what practical use it would be to MI5 is unclear. In sharp contrast to this are denunciatory letters from members of the public whose levels of sanity and paranoia vary widely.

Some letter writers denounced Claud as a Comintern superagent at the centre of a vast conspiracy, and others were evidently the victims of practical jokes perpetrated by my father: one woman reported how she had sat next to him at some dinner, and, having heard that he was radically inclined, had asked when he expected “The Revolution” to take place. She was horrified to be told by him that just such an uprising was planned for the following Thursday and would, furthermore, take place in a surprising but strategic location: to wit, the guards’ barracks on Birdcage Walk near Buckingham Palace. Dismayed by this explosive disclosure, she wrote to a friend asking him to pass it on to the intelligence services.

The success of his joke would have given pleasure to my father, but not as much as the secret official monitoring of his career. More literate but no less furious are the letters and memos from government officials enraged by revelations of confidential information in what Claud modestly called his “little monstrosity”. They demanded that he be prosecuted, detained and generally put a stop to. Sometimes the offence is trivial: “to attack a civil servant by name is a cad’s trick,” writes one official. “Not so long ago he published a War Office circular which was marked, and was, secret.”

Senior mandarins joined in the chorus: Sir Robert Vansittart, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office, is reported to be “extremely angry” and was asking the Department of Public Prosecutions to act against Claud or simply warn him off (the request was turned down). Surprisingly, the MI5 investigators, for all their hard work, never took on board that a main source of the confidential information reaching The Week, as with Private Eye three decades later, was other journalists, who passed on news that their own editors and proprietors refused to publish.

Journalists, individually and collectively, will always be engaged in a struggle with propagandists, a contest that sways backwards and forwards

The Week closed in 1941, and almost two decades later, Claud became closely involved with Private Eye, which was then run by Richard Ingrams, its editor for many years, a close friend whose approach to journalism was very similar to his own. As its guest editor in 1963, at the height of the Profumo scandal, Claud disclosed the identity of “C”, the head of MI5, Sir Dick White, provoking the cabinet permanent secretary Sir Burke Trend to summon a high-level meeting to decide if Claud should be prosecuted.

Claud would have relished Trend’s defence of official secrecy as revealed in the cabinet papers, which outdoes the circumlocutions made notorious by the TV series Yes Minister. Trend wrote that “it is a matter not so much of concealing as of withholding and what is withheld is not so much the truth as the facts”. The officials consulted ultimately decided not to prosecute Claud, largely on the grounds that identity of C was known to a number of other journalists, which does not appear to have worried them at all, though they were outraged by the name becoming known to the British public as a whole.

How far have the challenges facing journalists dissenting from conventional wisdom changed since my father’s day? In one very significant sense their work should have got easier, since the internet genuinely democratises the ability to learn and disseminate news. It breaks down the walls of heavily resourced media monopolies and makes it possible for almost anybody to be in the news business. When working for the Financial Times in London in the 1970s and 1980s, I would have to go to the office and call up the FT library to get files full of newspaper clippings and governmental or commercial reports in order to write an article. Today I can do the same from home on my laptop or phone, and anybody in the world can access the same information as I do.

The media invariably exaggerates its own ability to find out the truth and to speak that truth to power

Unfortunately, a deluge of raw information does not make a good article or even make its consumer well-informed, because it does not change the necessity for good judgement in selecting which, out of the myriad of facts now easily available, are significant or meaningless, true or false, informative or designed to deceive. Claud used to say that people had the wrong idea about facts, imagining them to be like gold nuggets in the Yukon, which the investigative journalist, like a prospector of old, would find, dig up and pass on to the public. In practice, he declared, the journalist must make continuous judgement calls as to whether or not those same nuggets are made of gold or granite, relevant or irrelevant. The internet makes an infinite number of potentially newsworthy facts accessible to all, but this does not avoid the need for selectivity on the part of the journalist, and it has, in some ways, made their task more difficult because they risk drowning in an enormous ocean of information.

Since the First Gulf War in 1991 I have had the depressing feeling that it is increasingly the propagandists who are coming out on top and that accurate reporting is on the retreat

The fashion popularised by President Trump for denouncing news contrary to one’s own interests as “fake news” has heightened perception that facts, truthful or mendacious, are always a weapon in somebody’s hands. Propaganda and PR have traditionally got a bad press, but they are not a modern invention: the walls of ancient Egyptian temples are covered with hieroglyphs in which pharaohs claim nonexistent victories and deny actual defeats, much as Trump invariably does today.

Journalists, individually and collectively, will always be engaged in a struggle with propagandists, a contest that sways backwards and forwards but in which the victory of neither side is guaranteed. This may be true as a comforting general proposition, but since the First Gulf War in 1991 I have had the depressing feeling that it is increasingly the propagandists who are coming out on top and that accurate reporting is on the retreat. The causes of this are diverse: politics, finance and technology have combined to squeeze out those whose job it is to find out what is truly going on and to pass on news of it to the public. The internet has destroyed many fine publications and the Covid-19 pandemic looks set to eliminate many more.

These ill winds blow from many directions but their collective impact is to blight all types of on-the-ground news gathering – casualties include the provincial press in the US and Europe, as well as my own field of foreign reporting, a speciality that, in the last two decades, has been increasingly dominated by war reporting. Since 1999, I have been writing about Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Yemen and Syria, conflicts that are sometimes referred to as the post-9/11 wars, but in certain important respects predate the destruction of the Twin Towers.

Reporting wars is easy to do, but difficult to do well. Spreading disinformation is a component part of war, which is scarcely surprising. It stands to reason that people who are trying to kill each other will not hesitate to lie about each other. But protagonists’ ability to conduct information wars has gone up, while the ability to report objectively has gone down. Coverage of the Afghan and Iraqi wars was often inadequate, but not as bad as the reporting in Libya and Syria or its near absence in Yemen.

This has fostered misconceptions not just about matters of detail but about more fundamental questions, such as who is really fighting who, for what reasons, and who are the winners and losers. For instance, in Afghanistan in 2001, the British and American governments, backed by a supportive media, believed that the Taliban had been defeated when they had in fact retreated, were very much still in business, returned to war in 2006 and may today be in sight of victory.

‘Never believe anything until it is officially denied,’ Claud would say

In Syria, political leaders and media organisations convinced themselves that the fall of Bashar al-Assad was inevitable, while anybody with real experience on the ground in Syria could predict from 2012 on, with a fair degree of certainty, that this was unlikely to happen.

One should not be too dewy-eyed about standards of reporting 50 years ago, when most news organisations in Vietnam dutifully toed the official line about the impending victory of the US and its allies. The media invariably exaggerates its own ability to find out the truth and to speak that truth to power. But in Vietnam journalists were thick enough on the ground and free enough to operate to include a fair number of perceptive dissenters who exposed official lies.

What is new about reporting in recent decades is the much greater sophistication and resources that governments deploy in shaping the news. Where they do not have their own heavily manned press offices, they hire private PR companies. After Vietnam, the US military convinced itself – wrongly to my mind – that it had lost the war because of hostile media coverage. They were determined not to let this happen again, and one could sense this approach at work in the Gulf War of 1991, a conflict that was to set a pattern for war reporting in the coming years.

Life was not difficult for propagandists in that early period: Saddam Hussein was easy to demonise because he was genuinely demonic. On the other hand, the most influential news story of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the US-led counterinvasion was a fake. This was a report that in August 1990 invading Iraqi soldiers had tipped babies out of incubators in a Kuwait hospital and left them to die on the floor. A Kuwaiti girl working as a volunteer in the hospital told the US Congress that she had witnessed this horrific atrocity. Her story was hugely influential in mobilising international support for the war effort of the US and its allies.

In reality the Kuwait babies story was a fiction. The girl who claimed to be a witness turned out to be the daughter of the Kuwait ambassador in Washington. Several journalists and human rights specialists expressed scepticism at the time because purported eyewitness accounts were full of holes, but their voices were drowned out by the outrage provoked by the tale. It was the classic example of a successful propaganda coup: it was instantly newsworthy, could not easily be disproved, and when it was – long after the war – it had already had immense political impact in creating support for the US-led coalition going to war with Iraq.

Propagandists have prospered, but they cannot escape one crippling vulnerability: much of what they say is not true, and their mendacity is liable to be exposed

Propagandists and the masters of spin have prospered, but they cannot escape one crippling vulnerability: much of what they say is not true, and their mendacity is liable to be exposed by events. Their lies may be covered up or forgotten in domestic politics, but lost wars like Vietnam or Iraq – and as it turns out failure to halt or control pandemics – are more difficult to explain away.

My father launched The Week in the 1930s as the world descended into turmoil and people could see their incompetent governments for what they were. “Never believe anything until it is officially denied,” he would say, and his apparent cynicism, which he viewed as simply an obvious piece of political realism, chimed well with the popular mood of that era. A period of permanent crisis, not unlike the 1930s, now appears to be returning.

The past five years have seen the rise of populist leaders in country after country, and they employ similar strategies: scapegoating foreigners at home and abroad, controlling or demonising the media, lying about their achievements and purporting to deal with crises of their own concoction. Most of these leaders, from Donald Trump in Washington to Narendra Modi in Delhi, are failing abysmally to cope with a real earth-shaking crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic. The 2020s are likely to see a toxic and unstable political landscape similar to the 1930s and, in this time of troubles, a pressing need for independent journalism and journalists, as my father found 90 years ago.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments