‘The worst form of torture I experienced’: China’s war against Tibetan Buddhism

Condemnation of China by the west has been muzzled in favour of protecting trade interests but the social control, surveillance and crackdown of Tibetan self-determination goes on, writes Brian McGleenon

China’s system of ethnocide was born in Tibet under the ambitions of party official Chen Quanguo. This blueprint for cultural annihilation was then matured in Xinjiang when he was sent there as governor in 2016. But, unlike Xinjiang, where testimonies of mass incarceration and torture of the Uighur ethnic minority frequently reach the outside world, the Tibet Autonomous Region is completely closed off.

The high plateau is out of bounds for the foreign press and Tibetans who attempt to communicate their struggle to the international community face extrajudicial detention for committing “crimes of undermining social stability and inciting separatism”. This lack of access means only whispers of torment reach the ears of those beyond Tibet’s mountain walls. Whispers that tell of monks confined to the slow agony of the “tiger chair”, children split from their families and sent to militarised vocational training schools, and the forced labour camps where hundreds of thousands are having their culture and identity vanquished.

Tibet’s status in the global news agenda has gradually subsided since the uprising in 2008. Protests against the Chinese government’s persecution of Tibetans were scheduled to coincide with the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. The attempt by monks, nuns and non-monastic Tibetans to draw international media attention to their plight was met by a brutal crackdown by the Chinese military and police. However, since then, the condemnation from western governments has been muzzled in favour of protecting trade interests with Beijing and even Hollywood’s “Free Tibet” rallying cry has petered out, leaving Richard Gere alone and exposed in his activism.

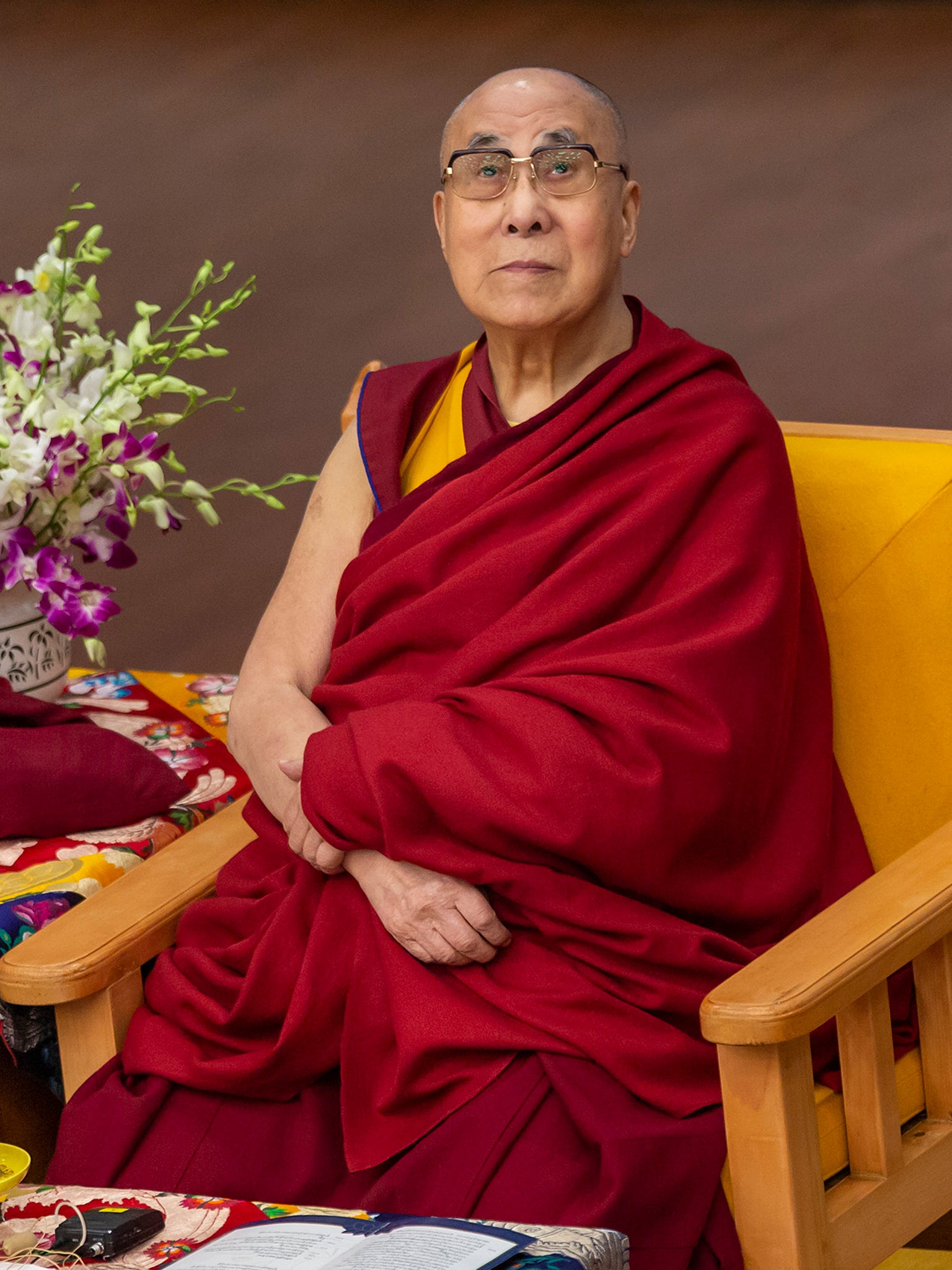

Also, the tragedy unfolding in China’s westernmost province of Xinjiang, with the cultural genocide of the Uighurs, has eclipsed the plight on the “roof of the world”. But, lack of coverage does not mean the question of Tibetan self-determination has been concluded. Over the past decade, China has been systematically developing its social control mechanisms in Tibet, building on the foundations set by Chen Quanguo, and under the jealous eye of the security-obsessed Xi Jinping. This renewed effort by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) comes as the world of Tibetan Buddhism prepares for the passing of the current Dalai Lama and the recognition of his reincarnation.

The vice president of the International Campaign for Tibet, Bhuchung Tsering, tells me the recent intensification of security apparatus in Tibet is focused on ensuring the “complete sinicisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the time of the succession of the next Dalai Lama”. The current Dalai Lama, now aged 85, has begun to implement the traditional framework to find and inaugurate his reincarnation.

Since he fled China in 1959 and set up a government in exile in India, it is predicted that his reincarnation will be found in India, beyond the control of the CCP. However, the CCP has insisted that all Tibetan Buddhist spiritual decisions come under the control of the party and they insist upon “total control of the process of selection of the next Dalai Lama”. In the past, the CCP sought to crush Tibetan Buddhism through the use of force and propaganda. China’s cultural revolution from 1966 until 1976 caused massive trauma to Tibetan culture.

Spiritual objectives are now not the first priority within the monastery, the new system is political and loyalty to the party is the first priority, leaving all spiritual priorities subservient to the dictates of the CCP

China’s Red Guards fanatically located and burned the “Four Olds”, old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas, wherever they could be found. The period saw routine public beatings of monks and nuns labelled “counter-revolutionaries”, and many of Tibet’s remaining monasteries were reduced to rubble by artillery and dynamite.

But, Tibetan Buddhism was more than its scriptures, monastic sites and ancient artefacts. It took in the violent assault with a unique acceptance and slowly exhaled it relatively unblemished. Confronted with this resilience Beijing has now changed tack, deciding instead to take ownership of the thing they could not destroy. Communist cadres are now involved in every minutia of the Tibetan Buddhist organisational hierarchy.

Every Tibetan monastery now has a management committee appointed by the CCP that monitors and directs the clerics. Bhuchuang tells me how the management committees are insidiously “changing the nature of Tibetan Buddhism”. He adds: “Spiritual objectives are now not the first priority within the monastery, the new system is political and loyalty to the party is the first priority, leaving all spiritual priorities subservient to the dictates of the CCP.”

Bhuchung describes how Beijing has promulgated a new procedure to ensure control of the reincarnation process before the current Dalai Lama’s exit from this world. The politburo has created a database of “living Buddhas” who are allowed to recognise the newly reincarnated Dalai Lama, and unsurprisingly the current Dalai Lama is not on the list. This database shifts spiritual authority from the monks in monasteries to the CCP, who appoint “living Buddha permits”.

In this way, they are sowing systemic corruption and competition within the monasteries for access to permits. Protection of the principles of the unification of the Chinese state is an essential criterion in attaining a permit. Tibet’s unification under the yoke of greater China is essential for Beijing’s long-term geopolitical goals. China sees Tibet as its “right palm” with the palm’s five fingers extending into Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh. Beijing still retains the long-term ambition of Mao Zedong, who vowed to “liberate” these regions.

This year, in his research, Professor Adrian Zenz of the European School of Culture and Theology in Korntal, Germany, has detected an increase in surveillance and security infrastructure of all types across the vast plateau. This process has also been detected by Buchung, who tells me that recently “there has been a steady move to take nomads from their lands to concentrate them in centralised centres”. Beijing’s securitisation of the rural regions comprises centralised training schemes for rural pastoralists and compulsory boarding schools for their children. The securitisation also entails more arterial transport routes suitable for the movements of large bodies of troops and military vehicles. Great effort has been expended in strengthening the fractious border with the Indian subcontinent, where digital surveillance posts and thermal monitors have been installed.

Professor Zenz’s 2020 study on the forced concentration of “rural surplus labourers” into centralised “military-style” camps describes hundreds of thousands of pastoralists and farmers subjected to “thought education” to eradicate “backward thinking”. The rural Tibetans are stripped of their traditional garments, dressed in military fatigues, and “transformed” for the labour needs of private companies and state enterprises. The hard-hearted process is all supervised under the impatient eyes of People’s Armed Police drill sergeants.

The CCP’s poverty alleviation report for Tibet describes the camps as striving to achieve two goals, to “dilute the negative influence of religion“ and erase the “weak work discipline” of Tibetans. Posturing as policies of poverty alleviation, farmers and pastoralists are processed to become loyal communist wage labourers. When a worker is “retrained” private agencies and companies profit from the subsidies for relocating the new surplus labour pool to regions that need it.

For those distributed within Tibet, the agencies receive 300 yuan (£34) for each labourer, and for those transferred to greater China, the agencies get 500 yuan for each transfer. Speaking of the new camps for the concentration of the rural Tibetans, Professor Zenz says: “Whether to become wage labourers or not, there is no choice. The rationale behind the scheme is that remote scattered people are harder to control than centralised factory workers.” He adds: “It is the most major assault on Tibetan livelihoods since the Cultural Revolution.”

Professor Zenz also explains how the state has sent out “village-based cadre teams” to break Tibetan lineage, roots, origin and cultural connection on the altar of socialist values and modernity. A particular focus is that deeply “ingrained stain” of the Tibetan Buddhist's viewpoint of the world, the antithesis of the CCP’s methodology of dialectical materialism. The teams of cadres have disseminated in groups of four or more across the vast plateau to be “constantly stationed” in Tibet’s 5,000-plus villages. The task is to make the remote regions “fortresses in the struggle against separatism”. Under the cadre’s watchful eye the people of the rural areas are reticent to pray in public and communist officials visit family homes to root out devotion that may be happening behind closed doors, a procedure known as “propaganda education visits to households”.

In the vast rural areas of Tibet a policy called “double-linked households” has been implemented, where the cadres that stalk the remote settlements encourage families to turn on each other and report any lack of loyalty or “acts of secession” to the local authorities. US-based Office of Tibet policy researcher Kelsang Dolma tells me of this “Orwellian social system” where “CCP officials spy upon Tibetans and then the ‘double-linked households’ policy comes into play where around 10 Tibetan families are ‘linked’ together and ordered to report and keep each other in line”. The insidious policy is designed to unravel the social fabric of these tightly knit communities.

Professor Zenz describes a different system of securitisation in the urban areas such as Lhasa and Tibet’s second city Shigatse. In the cities, there has been a reinforcement of “convenience stations” first developed by the meticulous Chen Quanguo. These concrete one and two-storey police stations divide the towns and cities into vast grids. In the Tibetan capital of Lhasa the closest two of these stations are only 15 metres apart. The convenience posts even exist in every monastery.

Vice president Bhuchung said: “The authorities have totally established themselves throughout every facet of life in Tibet to monitor and grind into submission the core of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly with the introduction of ‘convenience posts’ in monasteries.” Professor Zenz says: “The grid system in urban areas is designed to section off every urban block and neighbourhood and link households to report on each other to the security apparatus.”

The seventh Tibet Work Forum, held in Beijing at the end of August, saw the Chinese leadership expand on its policy of total control and assimilation in Tibet. The forum was entitled the “Strategy of Governing Tibet in the New Era” and it emphasised ensuring CCP organisations and members at all levels could “deal with major struggles” and any challenge to the power of the party. There was considerable emphasis on the phrase “ethnic solidarity”. The forum reinforced the need for China to fully sinicise Tibet before the succession process to choose the next Dalai Lama. The significance of the event was marked by the fact that Xi Jinping and the entire politburo standing committee was in attendance.

However, the most ominous development at the top-level meeting was the admission that efforts to convert Tibetans to love the “Chinese motherland” had failed. President Xi Jinping opened the meeting by stating the new priority was to “maintain the unity of the motherland and strengthen national unity”. The leader of China insisted there would be a new drive to revise the history of relations between Tibet and China that many of the population had got “wrong”.

Xi stated the Tibetan people would soon “come to a correct view of the country, history, nationality, culture and religion”. Communist China has inherited the traditional Achilles heel that has plagued every Chinese dynasty, the loss of stability, the great fear that the centre will not hold. At the Work Forum President Xi affirmed his commitment to forging ahead with “an ironclad shield to safeguard stability in Tibet”. Patriotism would now be incorporated into every school. Tibetan Buddhism would be recast in a “Chinese context”, and the public would be required to participate in “combating separatist activities”.

The policies outlined at the latest Work Forum have far-reaching implications for the lives of ordinary Tibetans. The proposals will amplify oppression on the streets of Lhasa or on the pastures of central Tibet. One example of such oppression is the experience of Tibetan monk Jigme Gyatso, who escaped from his incarceration and managed to attain political asylum in Switzerland. The harrowing account of his torture at the hands of Chinese security officials reminds us how sweeping totalitarian decrees can manifest as a nightmare for those individuals who are caught in the state’s crosshairs.

In China, when a person is categorised as a secessionist they lose the “protection of the state” and become a non-person with no recourse to legal representation and zero rights. Jigme came face to face with this reality when he spoke to a documentary maker about the Dalai Lama. For nearly one month he was forced to sit in the infamous “tiger chair”, day and night (China claims its torture chair is comfortable and is used to prevent prisoners from hurting themselves). Confinement in the chair for even a few hours causes blood to collect in the legs and lower abdomen causing the lower part of the body to swell. Jigme was confined to it for 22 days. Speaking to a UN committee he described how “it was the worst form of torture I experienced during my three detentions. My joints suffered horribly and at one point my feet became so swollen that all my toenails fell off.”

Jigme went through all this for his unwavering commitment to the Dalai Lama. Through their erasing of all imagery and reference to the current Dalai Lama, and through their infiltration of the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, the CCP hopes to harness the devotion of monks such as Jigme. They have a chance to direct the allegiance of the younger generation of Tibetans. A chance to subtly divert it to a love of the motherland, which translates as a love of the CCP. After all, the party values devotion above all other things.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks