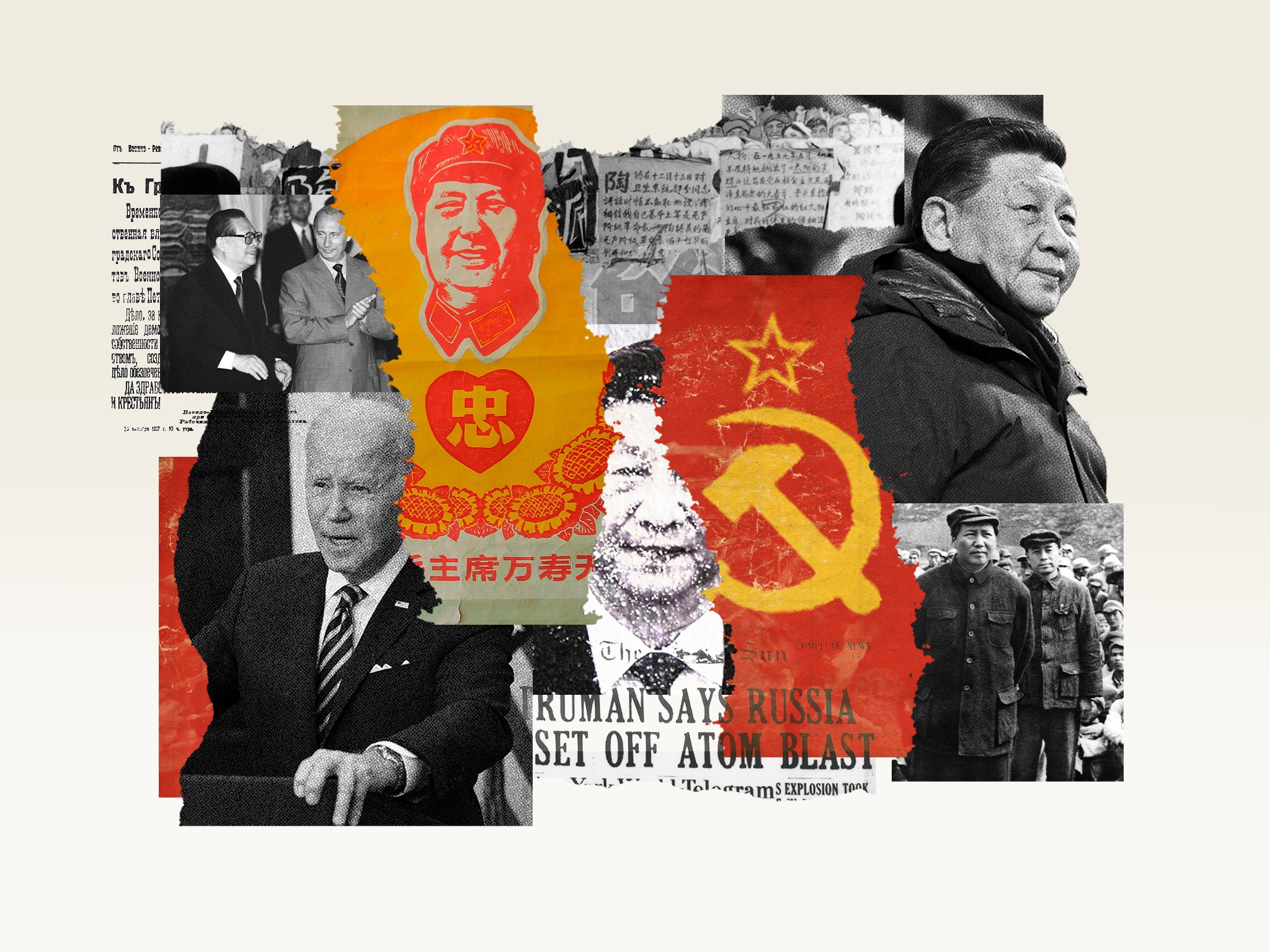

The Sino-Soviet split and the coming of the tri-polar world

The future of the world depends on how the three superpowers align themselves. Which side China takes will be important to global safety and if it picks Russia the future will be bleak, reports Sean O'Grady

Whatever Ukraine’s fate, the war has confirmed that we now live in a tri-polar world – where China, America and Russia form a kind of global triangle of power. It is evidently no more stable than many of the various balances of power that prevailed in the past, and indeed feels considerably more prone to things going wrong – simply because there are more “moving parts”, and more players to misread each others’ intentions.

But the future of the world, as with Ukraine, depends on how these three larger superpowers (with the EU as an economic superpower) align themselves. In practice, that means who, out of America or Russia, can recruit the Chinese to side with their cause and protect their interests.

If China chooses Russia, and forges an authoritarian-nationalist alliance, drawing in the likes of Modi in India, Erdogan in Turkey, Mohammad bin–Salman in Saudi Arabia and Bolsonaro in Brazil, then the prospects will be bleak indeed, for Ukraine and world peace. If President Biden can somehow revive China’s previous productive cooperation with the US and Europe, then the path the world takes will surely be happier, less violent and more prosperous – and China will not bankroll Putin’s war machine or sell him drones. It hangs in the balance, and while it does, there will be more wars.

To deploy an overused expression, ours is becoming, literally you might say, an Orwellian world. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell envisaged a world made up of three superpowers – Oceania, Eastasia and Eurasia, which has a familiar feel to it. As Orwell wrote in 1949: “The splitting-up of the world into three great superstates was an event which could be and indeed was foreseen before the middle of the 20th century.”

Worryingly, they were continually at war in shifting alliances, and of course people couldn’t trust the news…

Consider the broad history. Before the Great War the world was dominated by the two emerging blocs on the European continent – the entente powers of Britain, France and a Russia against the triple alliance of Germany, Austria and Turkey. A bipolar balance of power, though it failed to keep the peace. Between the wars America reverted to isolationism and Russia opted to build socialism in one country; and again Europe divided into two blocs, allies and axis. After the Second World War we lived in an obviously bi-polar world, particularly after the Suez crisis, when the British Empire could no longer command the status of a member of the “Big Three” that had won the war, under the remarkable and sometimes uncomfortable leadership of Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill.

The two nuclear superpowers maintained a sometimes precarious balance of power via the doctrines of nuclear deterrence and mutually assured destruction. Ideological and power struggles were played out by proxies, from the jungles of Vietnam to the Angolan bush to the mountains of Afghanistan. The 1962 Cuban missile crisis proved that when there was any risk of Russians and Americans clashing directly war would be averted by the fear of mutual thermonuclear destruction of life on earth. (The reluctance of Nato to engage directly against Russian pilots over Ukraine is an echo of that same mentality.)

America won the Cold War, with the USSR in 1991 collapsing under the weight of its failure to satisfy the material aspirations of its population (Vladimir Putin, take note), and the world became mono–polar. China was populous and had a big army, but that was about it. Only in 1972 did Mao decide to re-engage with the world diplomatically. Richard Nixon’s famous visit a half-century ago was the very beginning of the outward–looking China of today.

After the diplomacy came economics. Having only tentatively re-joined the world economy in 1978 under Deng Xiaoping, China was not ready to throw its weight around, and was more interested, sensibly, in establishing an industrial base to underpin its foreign policy ambitions.

In the 1990s and 2000s America had the world pretty much to itself. Envious European leaders such as Jacques Chirac could only fulminate as George W Bush implemented his new world order on a unilateral basis, and made wars and pursued regime change as he wished. Even Tony Blair, adept at managing the “special relationship”, was informed in 2003 that America was going to invade Iraq whether the British, or the UN liked it or not.

Now, though, the balance of power has shifted again. We have a tri-polar system, but the sides of the triangle, so to speak, are uneven rather than equilateral. It is an irregular triangle, one every sense. Russia has its huge nuclear arsenal, which presumably works more efficiently than its poorly-organised, badly-led, inadequately-equipped conscript army (something of a constant in its history).

But it has an economy around the size of Italy’s and its defence budget is hardly bigger than the UK. Russia is good at spying, space, mass production of shoddy goods, and possesses enviable natural resources – but that is it. America’s strengths of innovation in technology and the sheer size and capacity of its armed forces speak for themselves; but, as a Donald Trump noted, America’s old industrial base has been badly damaged by the globalisation it once enthusiastically embraced – not least by the imbalanced economic relationship with China.

The dramatic tilt in German policy away from pacifism and towards rearmament may change things, but for now Europe’s security interests are devolved to Nato under continuing American leadership

China needs America as a prosperous huge market; America needs China to lend it the money to buy more Chinese goods. They have been compared to two drunken giants, propping each other up as they stagger down the street, sometimes tripping over one another’s financial or geopolitical interests. China’s relationship with Europe is similar, but better balanced. China has its state-directed belt-and-road initiative as a form of latter day global economic imperials, buying influence and power everywhere from Sri Lanka to Greece to Jamaica. America has Wall Street, Apple and Disney. Russia has oil, coal and gas.

So we have three superpowers, each with strengths and weaknesses, none able on their own to push the others around. Europe, by the way, doesn’t much figure in this, apart from in the economic and trade spheres because, for better or worse, it still hasn’t developed a recognisable foreign policy and security “personality”. It was weakened in that respect by Brexit, just as the UK’s profile and clout is diminished without the economic heft of the EU behind its initiatives. The net result is that Europe/Britain has overlooked its opportunity to be the fourth global power.

The dramatic tilt in German policy away from pacifism and towards rearmament may change things, but for now Europe’s security interests are devolved to Nato under continuing American leadership. On the plus side, Nato has rarely been more vital, in every way, that it is now, and the nightmare of President Trump’s threat to withdraw has gone away. So, for now, Europe, save for the odd initiative by Emmanuel Macron, is content to tag along with Biden.

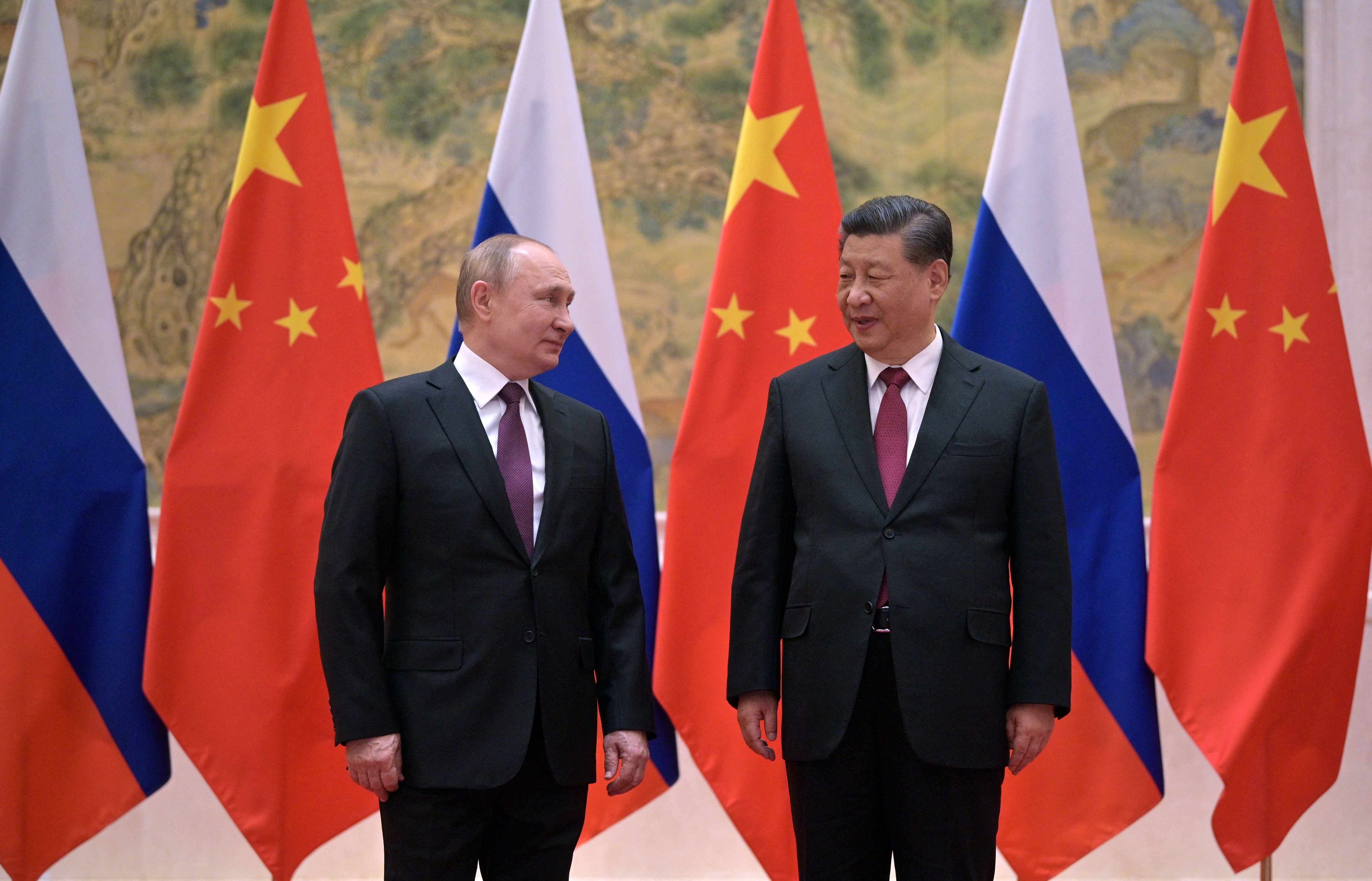

In this odd troika, with America and Russia already involved in an economic war and frictions in eastern Europe, China is pretty much the “swing state”. At the moment, then, the most worrying geopolitical development, albeit partly undermined and interrupted by Russia’s appalling performance in its ill-fated war, is the rapprochement between Russia and China.

At a summit in February in Beijing between Xi Jinping and Putin, the communique declared that there are “no limits” to their relationship, a phrase that should have frozen the blood of everyone in the west. They then pledged to “effectively counter external interference and threats to regional security, and maintain international strategic stability.” That is code for telling America to keep out of their respective spheres of influence.

Putin even, according to the stories, agreed to postpone his invasion of Ukraine until after the Winter Olympics in China were over. Incidentally, that timing may not have been ideal for Russia’s armed forces; the very cold weather has been quickly followed by a swampy, muddy Ukraine spring. In the lightning victory assumed by Putin that wouldn’t matter; but with his stalled campaign it meant his forces were bogged down and he handed an advantage to the Ukrainians.

Xi and Putin have much in common, leastways superficially. They both reject democracy (more or less politely and explicitly) as a weak and impractical way of dealing with the fast–moving challenges of the 21st century. (Much the same argument was used by the fascists and Nazis a century and more ago, when they thought decadent democracies were outdated and wouldn’t survive the modern rigours of the 20th century).

Putin and Xi are both nationalists of a revanchist type. Just as Putin wishes to rebuild the USSR and Tsarist Russia’s geographical span, so China wishes to solidify and mould a Macao, Hong Kong, Muslim Xiangjing, Tibet and Taiwan in Beijing’s image.

They are both dismissive of human rights and western progressive “woke” values (Putin reserving special horror for “gender fluidity”. They lead nations with a certain streak of (understandable) paranoia and inferiority about past western interventions in their affairs, particularly inhuman occupations by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan and Cold War hostility from the US. But they grew much closer once China, long-oriented and friendly to the US, found America had turned on it, and turned its indulgent, accommodative policy upside-down.

Trump, in a rather inchoate way, made enemies of both (notwithstanding whatever the Russians did to help get him elected) and undid decades of goodwill built up by successive American and Chinese leaders. He insulted China and its leaders, blamed them for the coronavirus – the “China virus” – started a trade war, cynically exploited genuine human rights abuses in Hong Kong and against the Uighur Muslim people, and refused to accept the basic truth that the Chinese were better at making things than America, just as the Japanese were before them.

Like dictators such as Kim Jung–un or Robert Mugabe, who told their people there was no food for them because of evil foreigners, so too did Trump use China and globalisation as a scapegoat for America’s own failings. Having encouraged China to embrace capitalism and globalisation, join the World Trade Organisation and make the yuan convertible and traded, the Americans started haranguing them for being too successful. Spurned by America, China looked abroad for friends, and Russia was the obvious suitor.

It should never have happened. China and Russia should be enemies, and for most of the last six decades they have been. One of the great, and fortunate, puzzles of the Cold War was why communist China and the communist USSR basically didn’t get on, despite their ideological affinities. Together, even in an era of American technological and industrial hegemony, they might have acted in concert with much greater effect. They were, after all, communist states. They didn’t, because they were, and to a degree still are, old-fashioned rivals for power. Because of that they made up a fairly bogus ideological reason for their schism – the Sino–Soviet Split. Ostensibly it was about who was entitled to carry forward the world communist revolution, who best represented the traditions of Marx, Engels and Lenin… Mao or the Kremlin?

After the Chinese revolution of 1949, sponsored by the Soviet Union, the pair were soulmates, and Mao accepted Stalin as the senior partner, given China was recovering from civil war and the horrors of Japanese rule. The Soviet Union was an atomic power, custodian of Marxist–Leninism, and Koba was the personally nominated inheritor of the legacy of VI Lenin (or so the propaganda claimed). It didn’t last, for two reasons. On the Russian side, Stalin’s eventual successor, Nikita Khrushchev (a Ukrainian as it happens) at first tentatively and secretly began a process of de–Stalinisation and denounced Stalin’s gulags, purges and his “cult of personality”.

By 1961 the break with the past was public, and the Chinese didn’t agree with it. Formally, they remained loyal to Stalin, and thus regarded themselves as the legitimate communists, and the Krushchevites as revisionists and deviants. They competed to mentor communist parties and guerrilla movements across the globe, though Albania alone initially volunteered for alliance with China (with Romania also a little sympathetic).

In reality, the breakdown of the great Sino–Soviet communist alliance was as much to do with Mao’s ego, the Russians’ patronising attitude, and, as a breaking point, Russia’s refusal to fully trust the Chinese with nuclear technology and secrets. That was the Sino–Soviet split of 1961, and it had far-reaching consequences, and advantageous ones, for the west.

America under Trump lost its friendship with China, but failed to counterbalance the loss through a rapprochement with Russia

After the split, the Chinese engaged in their own parallel Cold War with Russia just as the Americans were doing. So bad did Sino–Soviet relations become that by 1969 the pair were shooting at each other over an obscure border dispute, and almost at war, much to America’s alarm. The indirect consequence was the shadow diplomacy of Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, and his historic trip to China in 1972 (at a time when America still refused to recognise “Red China” and formally honoured the nationalist breakaway regime in offshore Taiwan as the legitimate government of the entire nation).

Nixon recognised that it wouldn’t be very difficult to court the Chinese and exploit their enmity towards Russia, and he went to town on it. An official note on the 1972 visit and a conversation with Chinese premier Zhou en Lai as follows:

“During the talks with Zhou, Nixon also made what amounted to a general security guarantee for China. Noting that during the South Asian crisis he had been ready to ‘warn the Soviet Union against undertaking an attack on China’. Nixon went even further, declaring that the “US would oppose any attempt by the Soviet Union to engage in aggressive action against China.”

Every president from Nixon to Obama made it their business to build an ever-closer partnership with China, and successfully play them off against Russia. The emerging superpower of China was firmly in the American camp.

But the more recent years of American hostility, ramped up by Trump, and barely dialled down by Joe Biden, have damaged the Sino–American relationship, though not irreparably.

Officially, China has shifted from being a partner of to being a threat to the United States, a stance mirrored in the UK and elsewhere, wary of Chinese control of key infrastructure, such as 5G and nuclear power. Justified or not, it has created a more dangerous threat in the form of a burgeoning Sino-Russian alliance. Where once upon a time, not so long ago, it would have been unthinkable for Beijing to supply high-tech kit such as drones to Russia, let alone prop up the rouble, that may be exactly what has been undermining world peace and emboldening Putin.

China and Russia, having started to normalise their relations in the 2000s, are closer than at any point since the 1950s. The 2001 Treaty of Good Neighbourliness and Friendly Cooperation between Russia and China was both bland and highly significant – the first equal treaty between the pair in history. The west was being cuckolded…

America under Trump lost its friendship with China, but failed to counterbalance the loss through a rapprochement with Russia. Despite Russian interference in American elections and the Trump victory, and Trump’s open admiration of Putin, once publicly trashing US intelligence to curry favour with the Russian autocrat, Trump never succeeded in making a partnership with Russia.

Let it not be forgotten either that Trump held up a military aid package to Ukraine while demanding a public investigation of Biden’s son, Hunter. The blackmailing of Zelensky to intimidate the Democrats also showed how far Trump was willing sacrifice Ukraine (and help Russia) for his own ends. Joe Biden was always going to be more wary of Russia – and the invasion of Ukraine finally slam Russian-American relations in the freezer.

To put things at their bluntest, America even with Europe, Japan and other allies can’t restrain two other superpowers simultaneously. It is no longer strong enough relative to the others to fight on two fronts, so to speak. It leaves the free world exposed. Perhaps one day a united Europe with Germany spending as much, proportionately on defence as America might rebalance the world again into a quadrilateral, but that will take some time. For now, America carries a heavy burden, and its voters, though outraged by Putin, are tired of foreign entanglements. After Afghanistan and Iraq, would they fight Russia over the fate of Romania or Estonia? You have to wonder.

There are limits, though, despite what they declared, to the new China-Russia alliance – and reasons for optimism. No more than any proud Russian nationalist, Putin does not wish to become economically, technologically and militarily dependent on a China – an exact reversal of the teacher-pupil roles the two nations played in the 1950s. Russia, as noted, can supply China with hydrocarbons and scarce raw materials – but it is a vastly less important market than America or Europe. China did not welcome Putin’s war in Ukraine, and at the UN stayed aloof and abstained: the war was bad for trade. At any rate, now it is China’s turn to emulate Nixon and Kissinger, and play America and Russia off against one another.

After the long phone conversation between Xi and Biden the other day, during which Biden again said he opposed Taiwanese independence, the Chinese “read out” was strikingly confident and assertive: “The US and Nato should also have dialogue with Russia to address the crux of the Ukraine crisis and ease the security concerns of both Russia and Ukraine.”

America can now be told what to do by China, just as China can use its industrial strength and technological prowess to tell Putin what to do. We have a tri-polar world, for sure, but one where one superpower is emerging as the driving force in world affairs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments