Kidnapping, trafficking and gang violence: Inside China’s quest to become an AI superpower

The Belt and Road Initative has brought an unprecedented influx of Chinese investment to the sleepy town of Sihanoukville in Cambodia. But, as Brian McGleenon discovers, with great capital comes even greater control

Ten Chinese men stormed into the Sihanoukville massage parlour and dragged 30-year-old Chanlina into a van waiting outside. Her screams alerted a nearby group of Cambodian tuk-tuk drivers, who approached the men and ordered them to release the Cambodian woman. Suddenly, they were surrounded by a hostile mob rushing out from an adjoining casino, armed with clubs, swords and knives. The ensuing battle was one-sided; several Cambodians suffered severe injuries.

The dark side of President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy endeavour, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has turned the once sleepy Cambodian fishing port of Sihanoukville into “New Macau”; the casino-lined streets now green with greed and red with violence. The city is a magnet for Chinese investors and migrant workers, a consequence of Beijing’s desperation to rid itself of spare industrial capacity, foreign currency reserves and a restless underemployed domestic workforce.

But moving at stealth behind the billions of dollars of concrete infrastructure lies “the digital silk road” – China’s developing web of surveillance and data gathering with its core at 135 Fuyou Street Beijing, under the watchful eye of the central intelligence agency United Work Front. If China is to realise its goal of becoming the world’s artificial intelligence superpower by 2030 then data is its most important resource, and its strategy in Sihanoukville is an integral component of achieving that dream.

Over the past ten years there has been an unprecedented influx of Chinese investment into Cambodia, specifically in the special economic zone of Sihanoukville, where the remnants of French-influenced architecture have been flattened by the concrete of a different kind of colonialism, manifested by Xi’s $1 trillion initiative.

Within these slabs of concrete run the veins of China’s nascent global surveillance and data munching imperialism. The fibre-optic cabling driving the facial recognition revolution of such companies as Huawei and ZTE come hardwired into the ports, railway junctions, hydropower dams, bridges and the subsequent casinos, condos, hotels and restaurants of the initiative.

Along China’s new digital silk road, connectivity means control, control from Beijing. The absorption of huge data sets from the recipient countries will increase the depth and diversity of China’s own data, with unforeseen consequences for the future of individual freedom and universal human rights.

Matt Sheehan of the Paulson Institute, a US-China thinktank, sums it up like this: “To become the pre-eminent global AI superpower China knows it needs data. If AI was a rocket, then data is the fuel, and the more data you have the further you can go.” Data is funnelled back to China through the land and maritime-based BRI fibre-optic cable routes built by the “effectively Sino state-owned” Huawei and ZTE.

Wang Shi Long, a Chinese developer who has relocated to Cambodia, says there are clear fortunes to be made in Kampong Som, the name many Chinese prefer to use for Sihanoukville. Apprehensively whispering, he tells me he thinks Sihanoukville will become the “next Shenzhen, which is China’s Silicon Valley”, adding: “We will make it a Cambodian Shenzhen, and developers must get in early.”

“Huawei is investing hundreds of millions of dollars to create the first phase of 500 base stations in the region, with Sihanoukville as a 5G hub linking China to Africa with fibre-optic underwater cables,” Wang tells me. He’s dismissive of the suggestion that the project has led to deterioration in quality of life for many in Sihanoukville, saying: “People can protest that China profits to the detriment of their Cambodian hosts, instead people should look at it from the perspective that Cambodians are benefitting from the huge surge in real estate development projects.”

To become the pre-eminent global AI superpower China knows it needs data. If AI was a rocket, then data is the fuel, and the more data you have the further you can go

Wang, who has investments in real estate linked to the BRI project, says that even poor Cambodians, many of whom are now unable to meet their inflated rents, will ultimately benefit when the infrastructure overhaul is complete, as the “trickle-down effect will create jobs and encourage Cambodians to better themselves”.

Huawei and ZTE offer “technology bundles” to the countries that sign up to the initiative, promising that cities will become smart cities, ports will become smart ports, all powered by Beijing-backed fibre-optic cable networks and satellite networks that lure in cash-strapped governments. In the short term, the benefits are easily seen, but in the long term countries like Cambodia will incrementally slip into line with China’s preferences, first at the regional level, then by extension at the global level.

What the Chinese Communist Party (CC) wants is not equal partnerships with co-signatories, but domination and control of the world order and to do this they must ensure their technology is indispensable. Fellow of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute Doctor Samantha Hoffman describes how the CCP “uses its technology to make its Gordian knot of political control inseparable from China’s social and economic development. The CCP’s development of smart cities are the embodiment of this strategy, allowing the CCP to blur the line between cooperative and coercive control.”

Like Sri Lanka and many African countries, Cambodia is now caught in the BRI money trap, where the state-owned Export-Import Bank of China lends money to signatory nations to build infrastructure that is integral to Beijing’s global strategy. The government then uses the money to commission Chinese companies to build the infrastructure. The government invariably defaults on the loan. China then takes ownership of the infrastructure as collateral.

The closer the Cambodian and Chinese governments cooperate through the BRI, the more detrimental the effect is on daily life in Sihanoukville. The city can be seen as a microcosm of the way Beijing relates to the nations it entices to join its initiative.

Anchaly, a local tuk-tuk driver who witnessed the attempted massage parlour kidnapping, tells me: “The abductions are becoming more frequent, as is the violence and abuse we receive on a daily basis. Sihanoukville now specialises in gambling and fly-by-night casinos. What happened that day shouldn’t surprise anyone, it has become commonplace. Just look, the Chinese now own 150 out of 156 hotels, nearly all the restaurants and all the casinos, karaoke clubs and most of the massage parlours.

“The Chinese have kidnapped many Cambodian girls. This is so they can be trafficked to China, to be auctioned off, to become the wives of poor farmers possibly.” This claim is supported by the findings of a 2018 Human Rights Watch report that describes the consequences of sex-selective abortion within China, which leaves many Chinese men without wives. Some families are willing to buy a foreign bride and human trafficking gangs are eager to exploit this.

People can protest that China profits to the detriment of their Cambodian hosts, instead people should look at it from the perspective that Cambodians are benefitting from the huge surge in real estate development projects

In order to appear as though they are taking a hard stance on the increasing vice in Sihanoukville, the Cambodian government enacted a law to ban online gambling in the country, which came into effect in January. Despite the ban, infamous triad chiefs are still flocking to Cambodia, including the notorious 14K leader Broken Tooth Koi.

The gang boss has launched his organisation’s headquarters in Cambodia and declared that its members would act as security for Chinese businesses in BRI countries. Beijing has welcomed this assistance, “as long as the triads are patriotic and will internationally forward Beijing’s interests”, according to former Public Security Bureau chief Tao Siju. Thus, these organisations have been lent a degree of respectability. So, when Broken Tooth launched a new gambling cryptocurrency in the capital Phnom Penh last year, senior Cambodia ministers of state flocked to welcome him.

The audacity of Sihanoukville’s triads has fermented a mixture of fear and loathing in the city’s original inhabitants. As Anchaly navigates his tuk-tuk through raw sewage and construction rubble, he reminisces how the former palm-lined streets used to lead to the azure Andaman Sea. Now, he makes a meagre living in what looks increasingly like a war zone.

“I don’t recognise my own hometown anymore,” he sayd. “Those areas not destroyed by construction look like they’ve been transported here from the middle of China. All of the money invested has gone into infrastructure that benefits China, and no investment in protecting the environment. I don’t see this as an economic miracle, I see roads littered with rubbish, raw sewage in the sea and our beaches clogged with plastic.”

But, BRI investor Wang disputes this, saying Sihanoukville “is a work in progress, there is still a shortage of capital, expertise and underdeveloped infrastructure. But, Chinese investment is transforming Cambodia so it can overcome these obstacles. Just as Sino capital transformed Shenzhen and made it what it is today, it will transform Sihanoukville.”

One Sihanoukville triad released a brazen video of a gang leader surrounded by his armed henchmen threatening to seize control of the entire city. In a message aimed to intimidate local Cambodians, the Chinese kingpin warned: “In the next three years, whether Sihanoukville will be safe or chaotic is under my control.”

I don’t recognise my own hometown anymore. Those areas not destroyed by construction look like they’ve been transported here from the middle of China

Exploiting easy pickings on the streets of Sihanoukville is not just the reserve of triad gangs: the Chinese state has also capitalised upon the insufficient public awareness of cybersecurity threats, personal data theft and unwarranted surveillance in Cambodia. Over the past few years the government in Phnom Penh has faced humiliation over the increasing number of Chinese operatives involved in cyberespionage offences, particularly operating out of Sihanoukville. This has led many cyber security experts to conclude that Cambodia is being used as a proxy by Beijing to launch cyberattacks in other countries.

What’s more, the Cambodian government itself could be implicated for using network backdoors to the benefit of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). Before the general elections in July 2018, a Chinese hacking group called TEMP.Periscope targeted the major opposition National Rescue Party and its leader, Kem Sokha. After data on his computer was maliciously altered he was accused of plotting to overthrow the government.

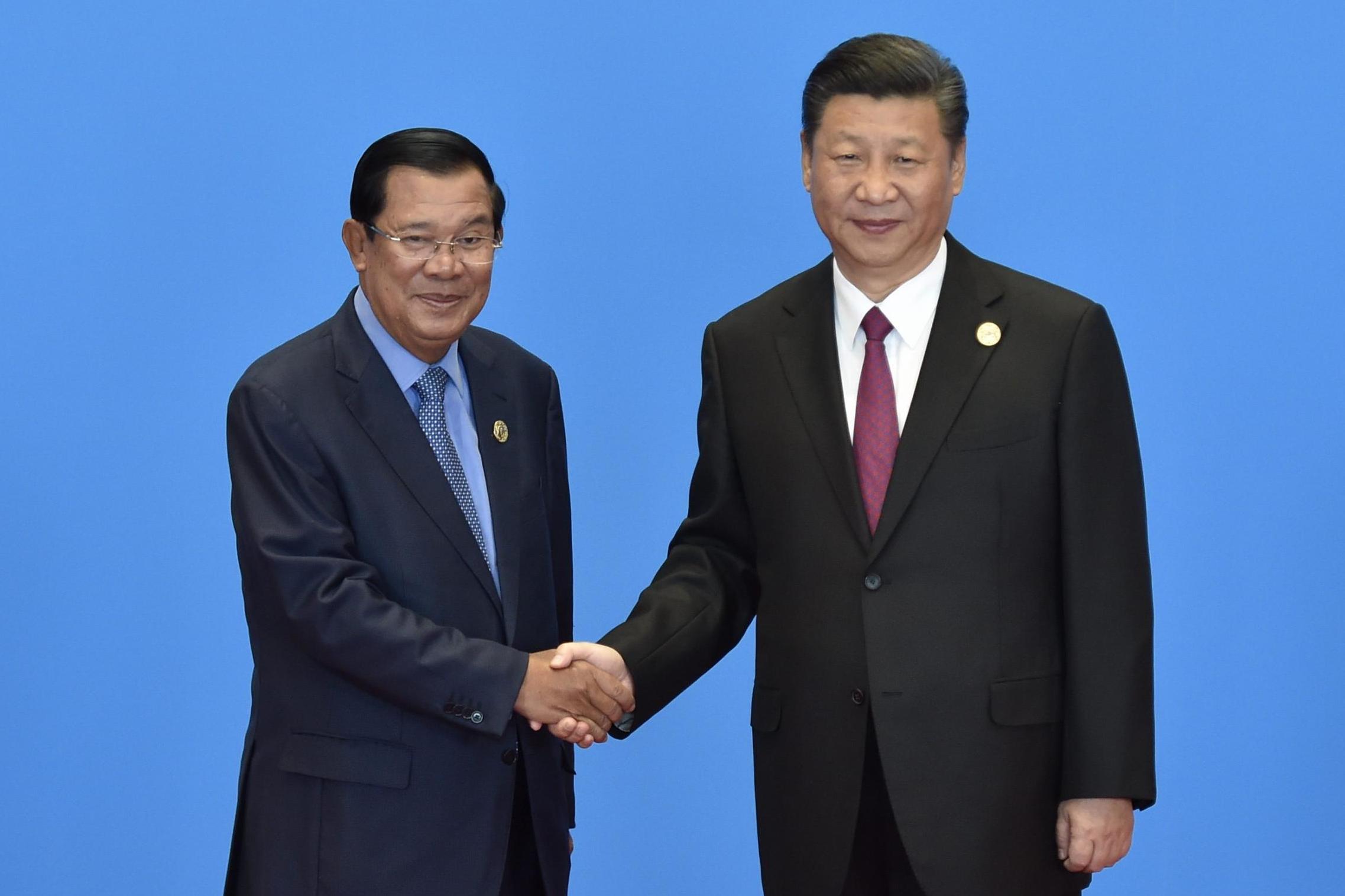

This led to Sokha’s incarceration, a ban on his party and the solidification of power under the Beijing-friendly Hun Sen, a relationship that goes back decades, into the darkness of Cambodia’s genocidal past. Prime Minister Hun was a local leader in the ultra-Maoist Khmer Rouge; during their reign of terror the regime received 90 per cent of its foreign aid from China. Now, that same Chinese money is propping up Hun’s regime, a man charged by Amnesty International with the persecution of political prisoners using “electric shocks, hot irons and near-suffocation with plastic bags”.

Wang tells me: “It was made clear by the ruling party that Sihanoukville will be built as a shining example of the Belt and Road Initiative. One of the key points of the initiative is delivering the good technology and the good culture of China to foreign countries.”

This dissemination of “good culture” to other countries is a cornerstone policy of the Communist Party of China, encapsulated by Mao Zedong’s “mass line” core ideology for ordering societies, which was reiterated at the last National Congress of the Communist Party of China. The term refers to a methodology for pressuring large populaces to fall into line with what is preferential for the party. The mass line encourages individuals to monitor their own behaviour, inducing both individuals and institutions to make the “correct” ideological choices and moral behaviour.

According to Doctor Samantha Hoffman, fellow of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, China is selling their “tech authoritarianism”, developed in the high surveillance environment of the Uighur concentration camp archipelago, to the BRI countries in the form of “safe cities”, or surveillance ecosystems.

Now, Beijing’s vigilant eye has gone global so that even Uihgurs who escaped to Turkey “still struggle to escape the CCP’s authoritarian reach”. This is due to Turkey’s recent signing of an agreement to “collaborate with Huawei on 5G smart cities development”. The ultimate aim is that the technology coerces populations to “correct” their ideological and “moral” behaviour, “so they will automatically make choices that uphold Chinese Communist Party power”, says Hoffman. She adds: “The CCP’s power-expansion effort does not stop at China’s geographic borders, largely because state security strategy is driven by the party’s political and ideological core. The CCP aims to reshape global governance.”

However, the claims that allowing Huawei to construct 5G infrastructure is a national security threat are disputed by Ma Jihua, a Chinese veteran of the telecommunications industry, who argues: “The Chinese company has been treated so unfairly. Huawei telecommunications software and hardware is safe. There have been no cyber security breaches in the past years.”

Sihanoukville is caught in the crosshairs of China’s unstoppable ambition to redress the indignities of the 20th century. From the enforced drug addition of the Opium Wars to the Rape of Nanjing, the crimes of “the century of humiliation” remain unresolved, open wounds in the minds of Chinese young and old.

Now the new “pioneers” are enthused by the words of President Xi with a spirit of manifest destiny, resolved to claim their entitlement in both the physical and digital realms. Determined to reset the world back to its original default, where China becomes Zhonghua Minzu once more, the centre of the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments