Charlie Wilson: Remembering a great newspaper man

Writer and curator Julian Machin first met Charlie Wilson in 1986 while interviewing for a junior position. Here he remembers the late editor and hopes to do him some justice

Back in the early days of News International’s Wapping plant and as a self-proclaimed expert on the works of the portrait painter Harold Speed, I was often driven around London in Charlie Wilson’s Jaguar, looking at paintings for him to buy.

Once I stepped from The Times office straight into the car and heat radiating from the indented seat surprised me. I asked Joe, the driver, why it was so hot and he said: “A’ve just dropped orf Rupert Murdoch,” as though that explained all. It might have led to a discussion in itself, but as I pulled the door closed the whole interior panel came away in my hand. “Don’t worry,” said Joe, “this one’s goin’ back shortly. Mr Murdoch was driving it last week an’ broke down,” adding, “On a roundabout. ‘E ’ad to push it.”

Many have said that Charlie was terrifying in the newsroom, being possessed of a verbal dexterity that would reputedly frighten the scales off fish. But I never saw it and I believe that his staff respected him. His authority came with decency, empathy and kindness, or else with an appropriate apology. We met in 1981 because he placed an advert in The Times and given that he wasn’t being charged for lineage, its succinct quality was testament to his taste for clear and concise copy: “Harold Speed, 1872-1957” is all it said, with a landline number. I was aged 19, and working unhappily for Antiques Trade Gazette, a weekly newspaper in Covent Garden. Intrigued, I called the number which rang through to his little corner office as the then deputy editor, located on the Gray’s Inn Road. From my first visit there, I knew that this was an exciting portal opening, but it wasn’t logical to imagine an onward journey lasting 40 years.

Charlie explained that he owned Harold Speed’s old house in Kensington, for which he wanted to acquire pictures. His openness to meet provided an index to his character. He didn’t exactly lack knowledge, but he was very good at finding and deploying people who amplified what he instinctively understood. Thus did we once debate a painting of a Grecian scene.

Charlie: “It’s the Acropolis.”

Me: “The Parthenon?”

Charlie: “Same thing.”

I first went on a Saturday to the house, and waited for him to detach himself from a distant telephone. Time passed; eventually, Sally (his then wife) swept through with champagne, gave me a glass of commiseration, and wafted away. It was 11.30 in the morning, and she’d been to view the sumptuous Argyll House nearby, but she told me she preferred theirs. I started to wonder at their world, not least because Charlie seemed quite earthed.

He advised me to use any contacts I could, any remote relatives or friends thereof to advance myself, because he’d had no such advantages. Eventually, I did ask him for a job and he interviewed me at Wapping. Afterwards, he sent me home via Joe and the Jaguar to mitigate the bad news, but he fought for me as a freelance, knowing it would be more appropriate. Ex-Gorbals and a Royal Marines prize fighter he may have been, but Charlie was never a homophobe and it was no problem for me in those days that he called me “Sweetheart”. John Russell-Taylor, formerly The Times art critic, who preferred to work very late in the office once told me of his sweet surprise when he felt someone’s hands over his eyes, which was Charlie tiptoeing up behind and saying, “Guess whoo?” I also came to realise that when being with certain people was difficult, he disguised it by acting with confidence that he didn’t actually possess. With others, he could be playful.

The timing of his jokes sometimes fell gratifyingly flat. As for those angry newsroom outbursts, he once told me that his rage towards his absent father was something that got put onto others, and afterwards he’d be terribly sorry, sending gifts to the unfortunates concerned who’d remember for the rest of time. Thus spread his reputation for stick over carrot but it wasn’t his core. Nor was he the philistine in the “Gorbals Wilson” column of Private Eye, a distortion he endured for too long.

At home in Campden Hill Square, we spent years procuring for the walls many paintings by Speed, almost as though we were returning them to the walls where they’d been hung before. More recently, I worked in vain to persuade him to at least let my firm auction his vast library of books after witnessing its dismaying spread to the full-size billiard table in the former painting studio.

Charlie was very well read and would have enjoyed participating in the dispersal of it, but he wasn’t a purist except about not selling things. It was noticeable that he had little affinity for other notable former inhabitants of the house such as the Llewelyn-Davies “Lost Boys” and JM Barrie, but he did in the case of Speed’s lodger, the poet Siegfried Sassoon.

When I lived in Bayswater we met in the evenings, drank too much, and he’d be very direct in asking about my life

We increased the number of paintings appreciably when works belonging to Speed’s daughter, Delia, were auctioned in the late 1980s. I alerted him from abroad, but couldn’t return to view or bid for him, so he did battle alone, only underbidding the lovely but battered Breakfast Time which reappeared within months at Sotheby’s where it fetched seven times at much. Curiously, Charlie didn’t seem to resent that. An alarming number of catalogues and boxes of ephemera filled the enormous lorry sent to collect it.

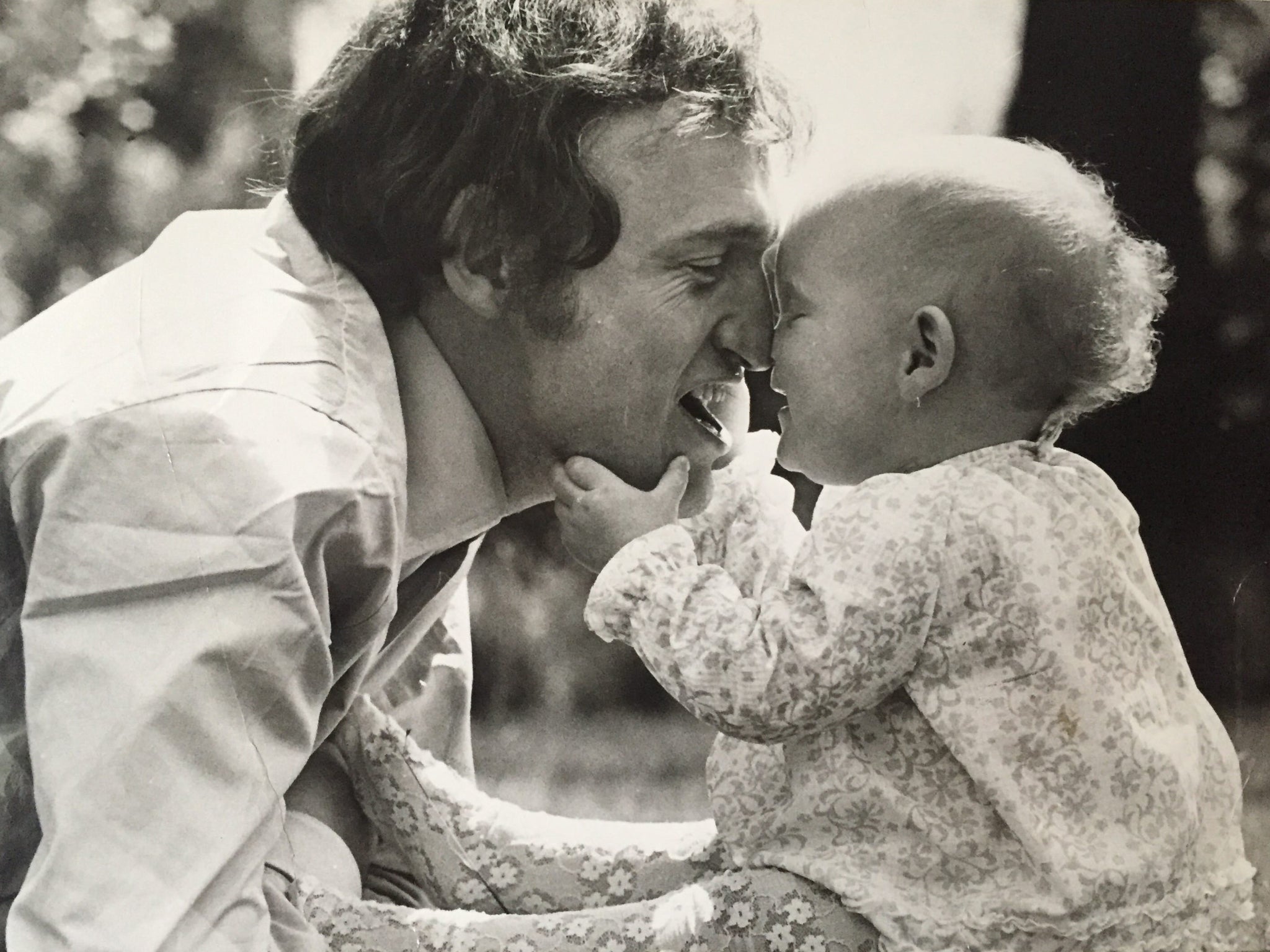

When I lived in Bayswater we met in the evenings, drank too much, and he’d be very direct in asking about my life. Once or twice, he’d volunteer stuff from his past. His third wife, Rachel, introduced him to things like the ballet, where we also met altogether. She was so good for him. I never saw him in the same room as Annie [Robinson] but he resented her Memoirs of an Unfit Mother – “How could she even remember?” – while from that marriage, his daughter Emma was another source of joy. An idea we had in 2019 for them to come to Portugal when he was longing for winter sunshine didn’t eventuate, though not because Emma’s preference was to take him to Agadir. He wasn’t well enough to fly, which was the first I knew that he was ill.

Later, we’d meet for lunch in Notting Hill. He was at first unchanged, still dapper, natty of dress and I was alone in contracting food poisoning from identical entrees at a smartish joint. Then we’d go to Pizza Express, where he’d manage only half of his order and I’d finish the rest.

During the first lockdown we mostly exchanged text messages which became slightly irregular. For the first time, he mentioned his aversion to trips from the farm to London for chemo. Little by little, his texts revealed what seemed to matter to him most: Rachel, Vincent the cat, eight race horses, young and old, his laptop. Christmas bliss without children and grandchildren, then bliss with them.

Finally came: “Not been at my best…Will contact you in a few days. C.”

When nothing materialised, I called darling Wendy Henry, former News of the World editor, and after getting a bit stuck on Charlie being (then) 86 without our noticing, and what it sodding well meant for each of us, she recounted the two of them facing Murdoch during the ghastly Tuesday meetings of all the editors. ‘He was brutal, brutal with Charlie, demeaning him with, ‘It’s not The Times, and you’re lowering the tone’ when he really wasn’t.” Ironic. Charlie was as capable as he was kind, generous, clever and extraordinarily tough out of necessity. Perhaps not much known about, while working for Robert Maxwell seeking to buy the New York Daily News in some secrecy, is Charlie having to telephone on Maxwell’s behalf and negotiate with denizens of the local printers, who seriously made Wapping seem like playschool.

Although he wasn’t an obvious candidate for a knighthood, though it may also have been an injustice, I think he’d have refused on the grounds that no self-respecting cat allows a tin can to be tied to his tail.

My final, unanswered text to him included an image of a drawing by Speed which was coming up for auction: “Lovely study… not of Speed’s lovely mural at the Academy… which reminds me: do you remember pulling up at the RA, driven by Joe, and ending our conversation with ‘I think I’ve got to go. The PM has seen me through the window and is wanting to talk. The drawing comes up on Monday; I will try to buy it as a memory’”.

That grocer’s daughter famously wreaked havoc that night at the RA with the entire arts budget, but I’m unaware of any harm directly caused during the extraordinary, maverick life of Charlie Wilson, the miner’s son.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks