‘A spectacular show’: How a Swiss chateau museum is bringing Charlie Chaplin back to life

In the many biographies and documentaries about the man, the 25 years he spent at his mansion in Switzerland are hardly mentioned. William Cook returns to Manoir de Ban after a decade to find a show fit for the most famous comedian who ever lived

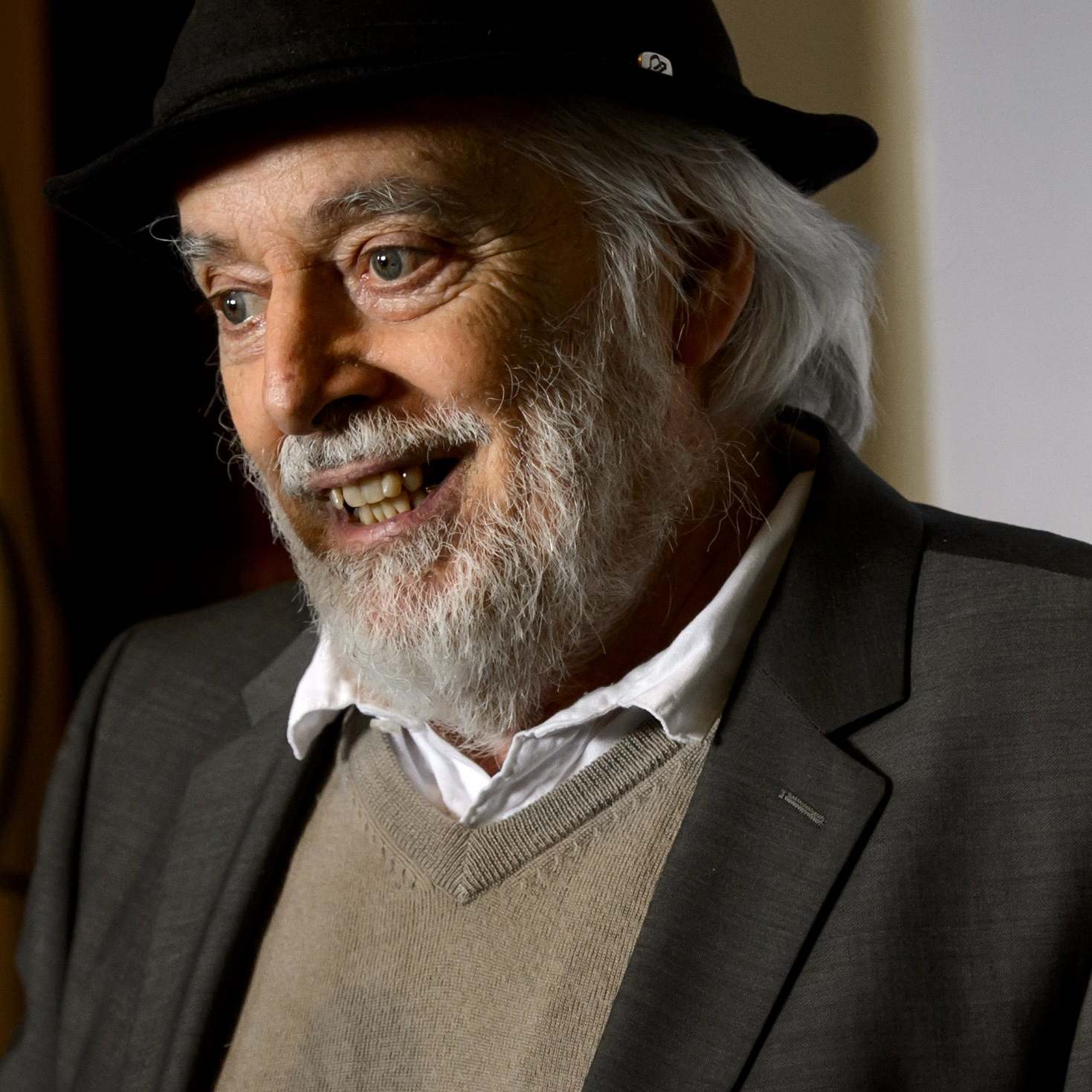

Nine years ago, on a cold midwinter morning, I travelled to the Manoir de Ban, a Swiss chateau in lush parkland on the northern shore of Lake Geneva, to meet Michael Chaplin, the eldest surviving son of Charlie Chaplin. The huge white house was deserted. No one had lived there for years. It felt like a scene from a film noir: The Third Man meets Citizen Kane.

Charlie Chaplin bought the Manoir de Ban in 1952 after the US authorities barred his re-entry into the United States, on account of his “moral turpitude and communist sympathies”. He’d sailed to England with his fourth wife, Oona (daughter of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill) to show her his childhood home – the mean streets of south London where he was born and raised (and almost starved).

Mid-Atlantic he was informed that he could not return to America, his adopted home for the past 40 years until he’d answered these trumped-up charges. The US attorney general called him “an unsavoury character” with a “leering and sneering attitude”. Doubtful that he’d receive a fair hearing, Chaplin decided to relocate to Switzerland. He lived in the Manoir de Ban for 25 years, until he died, aged 88.

Michael’s friend and business partner, Yves Durand, meets me outside and takes me in and shows me around. Most of the rooms are empty but Chaplin’s study is still just as he’d left it. Here was his desk, where he wrote his autobiography, and his grand piano and his library – hundreds of leatherbound books, all the classics. His favourite author was Dickens, and no wonder – his harrowing account of his early life reads like Oliver Twist. In the cellar were a few dusty film canisters. One bore the handwritten title Modern Times.

I’d come to Switzerland to hear about Yves and Michael’s plans to turn this house into a museum, a monument to Charlie’s life and work. Their ideas sounded far-fetched, fantastical – I thought they must be mad. Charlie Chaplin had been dead for more than 30 years. It was more than 70 years since his last great film, The Great Dictator. Sure, I was a fan (always have been, always will be) but I was nearer 50 than 40, and most of his fans were even older. Was there anyone left alive who’d seen his silent movies first time around? Did anyone under 30 remember him? Did anyone still care?

I liked Michael a lot. For all its apparent perks, being the son of a famous father can be a miserable business, especially if you’re intelligent, sensitive and self-aware, as Michael clearly was. It sounded like it took him a long time to escape his father’s shadow. I wished him well with his madcap scheme, and went back to London and wrote up my story. It was a good story but I doubted his museum would ever see the light of day.

Last week I was back at the Manoir de Ban, amid a crowd of sightseers. That museum is now up and running, at a cost of 60 million Swiss Francs (£48m). Last year a quarter of a million people came here from all around the world, from as far afield as India and Japan, to learn about the most famous comedian who ever lived. There were young families here today – children whose parents weren’t even born when Chaplin died here, on Christmas Day 1977.

As Michael said of him: “He created a universal character. Everyone could identify with him because he represented things that everyone could recognise in themselves.” Chaplin’s World confirms that Charlie Chaplin’s appeal is timeless. I’m happy to report that Michael was right, and I was wrong.

He created a universal character. Everyone could identify with him because he represented things that everyone could recognise in themselves

Chaplin’s World isn’t only a museum, but neither is it a mere theme park. It’s actually a bit of both, which I reckon is just the way Chaplin would have liked it. Like all true clowns he was deeply serious, an earnest autodidact with a keen interest in philosophy, politics and economics. But above all, he was a showman, and Chaplin’s World is a spectacular show. You walk through the sets of his greatest films, littered with cinematic history, before entering the mansion where he spent more than a quarter of his life.

Yet in the countless Chaplin biographies and documentaries, these 25 years are hardly mentioned, a quarter of a century compressed into a brief epilogue. So what did Chaplin get up to during this final act, this long curtain call? And why is it just a footnote in the accounts of his long life?

Chaplin came to Switzerland from London in the autumn of 1952, fresh from the premiere of his latest movie, Limelight. He’d wanted to launch the film in London because it was a homage to his theatrical beginnings in the Big Smoke – the story of a washed-up music hall entertainer (not unlike his own father, a hopeless alcoholic) who finds redemption when he rescues a suicidal ballerina (played by Claire Bloom). As it turned out, this was the last film he ever made in America, and it wasn’t even shown there until 1972, when he returned to the States to receive his (belated) honorary Oscar.

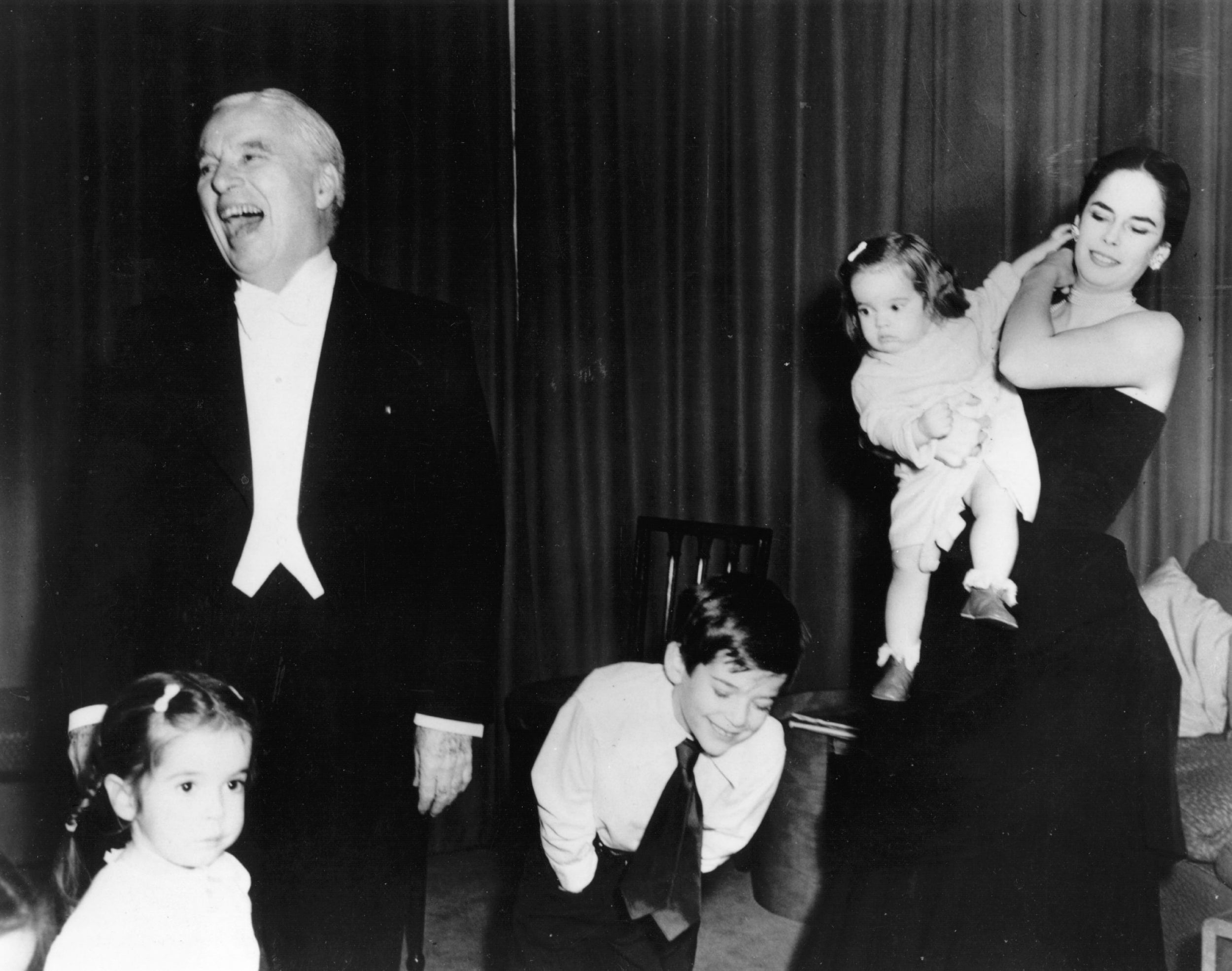

Michael Chaplin was six years old when his parents brought him to Switzerland, the second of their eight children (four were born in America, four more in Switzerland). For a while they lived in the Beau Rivage, a grand hotel in nearby Lausanne, before moving into the chateau. “He walked us around the park,” says Michael, recalling the first sight of his new home. “The big trees, the forest, all that space – it seemed like a dream.”

It sounds like an idyllic childhood – that huge house, all those siblings, all that parkland to play around in. The children attended the local school, and soon spoke French just as well as English. The local market town, Vevey, was quiet and unpretentious. “My father could walk down to Vevey and go and eat in restaurants. He never got mobbed.” For someone who’d been the most famous man on earth, it must have made a pleasant change.

It was certainly a world away from Chaplin’s Dickensian childhood: a father who drank himself to death before he was 40; a tormented mother who ended up in a lunatic asylum; a spell in the workhouse, a spell in a children’s home... Chaplin loved his children and wanted the very best for them, but he was a domineering father who demanded obedience from his offspring and was quite prepared to chastise them when they stepped out of line. For a man born way back in 1889, this was not unusual, but these Victorian values were increasingly out of step with the modern world.

The same could be said of Chaplin’s post-war movies. In 1957 he made A King in New York (shot at Shepperton Studios in England), his first film since leaving the US. In an ironic reversal of his own exile, he played a deposed European monarch seeking sanctuary in America. The film was a satire on the America he’d left behind. Chaplin cast his son Michael as a precocious child with an interest in Marx who nonetheless insists he is no Marxist (a succinct summary of his father’s politics). Chaplin called it “my best picture”. The New Yorker called it “maybe the worst film ever made by a celebrated film artist”. The truth lay somewhere in between. The film was not released in the United States until 1973.

For Michael, making A King in New York was a high point (“I was happy to have this relationship with him, which I never had before,” he reflected, poignantly) but other people had less happy memories. Eric James, who worked on the music, noted the frequent “arguments and bullying” that were aspects of Chaplin’s “fiery temperament”. His stenographer, Isobel Deluz, recalled “his first-rate clowning, his second-rate manners and his sixth-rate philosophy”. Always a dictatorial director, Chaplin showed no sign of mellowing with age.

Back in Vevey, Chaplin set to work on his greatest post-war production, his autobiography, which was published in 1964. As with his movies, he insisted on total control, which has bequeathed an invaluable record – a book which reveals what he really thought, rather than what a ghostwriter thought he thought. The book is an unwitting testament to the deadening effect of fame.

The first half (about his early life, before he became famous) is a heartfelt masterpiece. The second half is bland – evasive about his complicated private life (three of his four brides were still teenagers when he married them) and strangely incurious about the art of movie-making (Stan Laurel, who worked with him in the early years, isn’t even mentioned). He asked Truman Capote to read the manuscript, but when Capote suggested some changes Chaplin lost his temper. “I don’t need your opinion,” he told him. As Peter Ackroyd relates, in his astute biography, he never spoke to Capote again.

We didn’t have television because he thought television was the enemy of cinema and would destroy cinema. He wasn’t entirely wrong

For Chaplin, one of the attractions of Switzerland was its relative proximity to his native England. His doctor and his tailor were both in London, and he made frequent visits to his hometown, seeking out places from his childhood, attending pantomimes and staying at the Savoy. He took Oona to Southend, the site of a rare day out with his mother. He liked wandering around London incognito, but he was often recognised – too often for his liking. He would always be far too famous to lead a normal life in England.

In Switzerland, he had no such trouble. The Swiss are famously discreet, far too cool to gawp at superstars. He took his children to the local cinema and to the circus, when it came to town, but otherwise they lived a quiet life – dinner at 6.30pm, bedtime at 9pm, no TV in the house. “We didn’t have television because he thought television was the enemy of cinema and would destroy cinema,” Michael tells me. “He wasn’t entirely wrong.” Michael eventually rebelled against this affluent austerity. At 16 he left home and went to London to become an actor. He subsequently published a memoir called I Couldn’t Smoke the Dope on My Father’s Lawn. “I never argued with the old man,” he wrote. “I never dared to. In any case, it’s useless to argue with my father. He is too stern, too inflexible, too overpowering.”

This opinion was echoed by Marlon Brando, the star of Chaplin’s final, ill-fated film, A Countess from Hong Kong, filmed at Pinewood Studios in 1966. “You can see why actors find him difficult,” observed silent movie star Gloria Swanson, after visiting the set. Brando went a good deal further, calling him “fearsomely cruel”, “an egotistical tyrant” and “the most sadistic man I’d ever met”.

He had one more film in him, but he never made it. The Freak was a kind of fairytale about a young woman who sprouts wings and becomes an object of lurid curiosity. He wrote it for his daughter, Victoria, but then she ran off to Paris with a French actor, to start a circus. “I gave her everything she wanted,” Chaplin told Eric James. “Why should she repay me in this way? She will never – and I mean never – set foot in this house again!”

And yet, despite the tantrums, it seems Chaplin was happy – as happy as he could be – here in the Manoir de Ban. “I sometimes sit out on our terrace at sunset and look over a vast green lawn to the lake in the distance, and beyond the lake to the reassuring mountains, and in this mood think of nothing and enjoy their magnificent serenity,” he wrote. Those were the concluding words of his autobiography. The Tramp was at peace, at last.

For Chaplin, old age was a blessing and a curse. In his final years, he was confined to a wheelchair, a cruel end for a man who made his name as the world’s greatest mime. “He withdrew more and more within himself,” recalls Michael. “There was very little communication.” Death was kind to him (he died in his bed, in his home, surrounded by his family) but it was hard on Oona. “My mother was completely broken up,” says Michael. “It was terrible for her.” A teenager when she married him, she’d given her whole life to Chaplin. He was in his fifties when they met. Her father never spoke to her again.

Oona lived on here until she died, of pancreatic cancer, aged 66. “She had a very difficult time after my father’s death,” says Michael. “It left a big emptiness in her life. He was such a presence. He was a little man, but he took up a lot of space. You felt him when he was there, and for her to be without him was a terrible loss. I don’t think she ever managed to pick herself up after that.”

After his mother’s death in 1991, Michael and his brother moved in here with their respective families – 10 children between them. “It was a crazy time,” he says. “I wanted our children to enjoy it, which they did, but in the end, after 10 years, it had cost us a lot and we were in a bit of trouble. It was time to move on, so from there the idea of a museum developed.”

So what would his father make of the museum that stands here today? Of course there’s no way of knowing, but as I exit through the gift shop, full of Chaplin memorabilia, I think of something Michael said, all those years ago, when Chaplin’s World was just a pipedream. “He loved attention. He loved being popular. He was always conscious of his audience. So if this place works and there’s loads of people coming here, if he’s anywhere that he can see this, he’ll be pleased.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks