My colleague, the paedophile

After a Cambridge professor was allowed to return to work having been suspended for, and then convicted of, possessing, making and distributing images of child pornography, Andy Martin objected

Would you give a job to a convicted paedophile? No, neither would I, especially not as a teacher. Cambridge University thinks otherwise. The question is: why? I sometimes wonder: does he include his conviction on his CV? Probably not. I just looked up his webpage: it doesn’t mention it there either.

“Professor M” (as I will call him) is a colleague of mine at Cambridge. For around 10 years I’ve tried to forget about it, and then, quite recently, I got a letter addressed to him in my pigeon-hole and I thought: just hold on, he is not me, I am not him. He’s the paedophile, I’m not. The university seems oblivious to the difference.

I may be guilty of having kept quiet about it for too long. But the fact is I went to the trouble of setting out my objections to their decision all those years ago when he got his old job back. He had been swept up in a police paedophile unit operation, duly arrested, put on trial and convicted. He was found guilty of possessing, making and distributing child pornography, including images of babies, more than 1,000 photographs and videos of boys from two days old to teenagers, with some of them classified as “level 5”, referring to images involving bestiality or sadism.

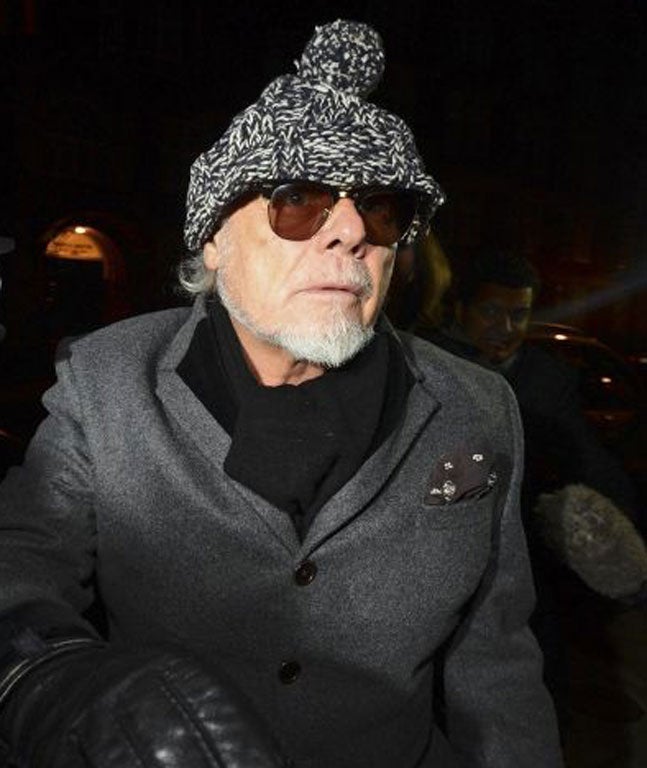

A lenient judge, a Cambridge graduate, sitting at Cambridge Crown Court, who referred to him being “an intelligent man” yearning for his “halcyon youth”, handed down only a year’s jail time, suspended for two years. And a fine of £1,000. Professor M was a free man again, even if now included on the sex offenders’ register. It was surprising that the sentence was not reviewed on account of being too light (the norm at the time for comparable offences was months or years inside: in the US one man was given 10 years; Gary Glitter was sentenced to four months for his first offence).

In his defence, Professor M claimed that the most serious images were downloaded accidentally. He really only wanted to gaze at pictures of teenage boys, mainly in swimming trunks. At the time, the director of a child protection charity said: “This is a sickening betrayal of justice. It would seem that the awful abuse these children suffered is not very important if you're somebody as grand as a Cambridge professor. Had he been an ordinary working man he would've been sent straight to prison. This is an appalling case where more than 1,100 children have been the victim of sexual abuse for his gratification. The message is… he is somehow above the law as a professor.

Professor M was living in university accommodation when he was arrested, together with his child porn-laden laptops and memory sticks. He had been suspended (on full pay) while the trial was going on. After the verdict, the university, in its wisdom and benevolence, under its then vice-chancellor, professor Dame Alison Richard, decided it would be just fine to let a convicted paedophile carry on teaching, as before.

The following statement (where Professor M appears as “X”) was issued on behalf of Alison Richard at the time and recently reiterated: “This was not a decision which the university took lightly. It involved very serious and careful consideration of all the competing interests in this case. The university is clear in its repugnance of the crimes for which X has been punished by the court. The vice-chancellor expressly recognised the very understandable and legitimate concerns of the victims of X’s crimes, as well as the genuine disquiet which colleagues, students, parents and funders would feel if X continued to remain as a member of staff. But she also necessarily took into account the findings of the medical experts in the criminal proceedings that a clinical diagnosis of paedophilia could not be made in this case and that X was highly motivated to heal himself and had sought psychotherapy voluntarily.

I like Professor M on a personal basis, but it is obviously impossible to have him back in the department, as if nothing had happened. He should never be allowed to work with young people

“There was no evidence that he had ever conducted himself inappropriately towards children or his students and the judge sentencing X had expressly concluded that the greater public interest required X to be given the opportunity to rehabilitate himself under strict conditions. These include a period of supervision of two years in which X is required to complete the Internet Sex Offenders’ Treatment Programme. He has also been required to register under the Sex Offenders’ Act for a period of 10 years and has additionally been banned from working in a voluntary or paid capacity with any child under the age of 16. If there is any breach of the conditions imposed on him, then X is liable to receive an immediate prison sentence and the university would reconsider his case under its disciplinary regulations.”

We (his colleagues) were given the opportunity to express an opinion. Naively, I took the process seriously. I wrote to the bigwig responsible roughly as follows: “I like Professor M on a personal basis, but it is obviously impossible to have him back in the department, as if nothing had happened, as if he’d just been on sabbatical for the past year. He should never be allowed to work with young people.”

I said that it was not “a trivial offence” and that turning a blind eye was not only an insult to survivors of sexual abuse but would alienate students, parents, alumni and potential donors around the world. I felt slightly awkward having to state the blooming obvious. But of course the whole process was a sham, a tenuous and semi-transparent fig leaf in front of images of naked boys. My objection was “noted”.

Over in Oxford, at one of the science labs, in a very comparable case, without any of this kind of special pleading, the offender was summarily sacked. “An easy decision to make,” said one HR specialist.

Meanwhile, in Cambridge the justification floated by the university was along the lines of giving him “a second chance”. By all means. But clearly not in the realm of teaching. We don’t do courses on child porn. I was told (in the official reply to my objection) that there were “widely differing views” on the matter. How can views differ that widely when it’s a matter of the sexual abuse of children? It’s not even complicated. There is no need to assume a moral high ground when the subject itself plumbs the depths.

The possession and production of images of child sex abuse is a heinous crime. The point that the anthropologist Alison Richard doesn’t seem to get is that no child consents to participating in porn films or being photographed naked. So by getting involved in this business (and more than 1,000 pictures means you are seriously involved) you are automatically colluding in harming children around the world, raping them, possibly killing them. Ernie Allen, president of the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children in the US, says that child pornography has become “a global crisis”.

But there are certain crimes that are so abhorrent, so manifestly beyond the pale, as to make a position at a teaching institution untenable

According to the National Crime Agency, 144,000 people based in the UK have been linked to paedophile websites. Oddly enough, a very similar figure of UK nationals are working in this country as academics. Statistically, some of them are going to be the same people.

The mystery remains: why would you actively seek to employ someone who has been convicted of being a paedophile? (The use of child erotica is seen as an indicator of paedophilia ie sexual interest in prepubescent children rather than actual child molesting, according to Dr Michael Seto in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology).

University students are not (except in rare cases) children, but they were, not very long ago. It is inevitable that some of those sitting in lectures (even virtual ones) and taking notes will have been victims of sexual abuse. Some of them may have children of their own. I have two boys (who were then within Professor M’s target group, with or without swimming trunks) and part of my role as a parent is to try and make sure they come to no harm. That would tend to exclude working with a convicted paedophile.

Sadly, the kids wouldn’t be dropping in on me in my office any more. The fact is we also have a lot of school children visiting from time to time, usually but not always in groups, potential future students, who will meet members of faculty. Which would include my colleague. Perhaps “accidentally”. We are also regularly called upon to give classes to schools. I’ve taught kids as young as 11 or 12. Has he?

Students do not give consent when they go to his lectures. I am unconsenting when it comes to working alongside him. But, inevitably, there is an implied complicity (and I have been feeling complicit). It was obvious to me that he should not be teaching at the university. And regarding the “second chance” theory, I would be happy for him to seek employment elsewhere, in some other form. Possibly caring for seniors, or teaching at the University of the Third Age, for example.

Far away from young people of whatever age. Or (like his Oxford counterpart) doing something in computing. Surely no other teaching institution, if they had an inkling, would be willing to recruit him. I know (having been through the procedure myself) that schools have to conduct a “police search” before employing anyone, no matter how briefly. Alarm bells would go off.

I know another professor who was found guilty of “armed robbery” and served time inside and, until his death, was working in the Academy. But there are certain crimes that are so abhorrent, so manifestly beyond the pale, as to make a position at a teaching institution untenable. This must be one of them.

Somewhere in the university statutes, it is written that you can be sacked for committing an act of “gross moral turpitude”. The word “turpitude” is fairly ancient, coming from the Latin turpis for base, shameful, disgusting or repulsive, and is not often used these days.

Looking up the Cambridge English Dictionary, I see that it defines it as “evil” and cites its use in this sentence: “It waxes in wickedness, moral turpitude knows no limit.” For a long while I struggled to imagine what would be bad enough to constitute gross moral turpitude. But it struck me that having a conviction for collecting child porn easily qualified for this unusual label. So, just for once, on a matter of morality, it was completely clear what the correct decision was as regards Professor M’s chances of future employment.

And yet, bafflingly enough, not to Cambridge. The university took a “widely differing view”. It thought that paedophilia and teaching were not incompatible. As was once said of Napoleon, “it’s worse than a crime, it’s a mistake”. The university was, in effect, condoning and thus compounding the original crime. Since I work here too, I want to make clear that I do not condone. I have been trying to work out exactly what is wrong with an institution that is capable of making such a manifest error of judgement.

The Pope hazarded a guess that 2 per cent of Catholic clergy are paedophiles. The number in the general population is unknown but if we allow the conservative estimate of 0.5 per cent (a figure proposed by Dr James Cantor, a psychologist at the University of Toronto), then among the approximately 8,000 academic staff employed by Cambridge, we would expect 40 paedophile-inclined faculty members. But even if this statistical approximation is anywhere near correct, it doesn’t mean that there is a “ring” at work. Paedophiles, for obvious reasons, tend to be secretive loners who are nevertheless able to share material online among anonymous communities.

An Italian criminologist once pointed out that the way the two universities of Oxford and Cambridge are structured is very similar to the Mafia. Colleges, in terms of the way they are set up, are like the families that are semi-autonomous but band together and collaborate to mutual advantage. But, to be fair, the resemblance is only at the level of structure, and only visible to sociologists.

According to its own figures, setting aside endowments, investments and central government support, Cambridge receives an average £271m every year in philanthropic donations

Universities exist to educate and carry out research, rather than to prosecute criminal activities. There is no network of gangsters here. On the other hand, it should have been obvious to the university that employing a convicted paedophile would give rise to the suspicion that there was something very strange going on. This was one of those times where the institution had to not only do the right thing, but be seen to be doing the right thing. To use a Mafia analogy, it seemed as if Professor M was being treated as a “made man”, given special protection and privileges from the establishment, his fellow “wiseguys”.

One of the differences with a criminal organisation is that whereas the gesture of protection may well enhance the standing of the Mafia, the university was risking reputational damage. It is not simply that potential students and faculty are less likely to apply to an institution with a record of employing known paedophiles, but there is the existential issue of funding.

According to its own figures, setting aside endowments, investments and central government support, Cambridge receives an average £271m every year in philanthropic donations. Notable donors include Bill Gates ($210m – from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation – with a whole building named after him and a bundle of scholarships) and the Mellon Foundation.

I have even given a lecture at an event for visiting American philanthropists, who were attending a lunch hosted by Prince Philip (back in the day when he was chancellor). In the UK, David and Claudia Harding recently donated £100m. None of these donors would be too keen to be associated with paedophiles, I imagine. Cambridge is a brand, like Mercedes or Manchester United. They are not going to knowingly put a paedophile in the driving seat or in a red shirt. But Cambridge doesn’t mind putting one in the classroom. It’s curious.

Of course, paedophilia was not always frowned upon. It was common among the ancient Greeks, for example. Pederasty, a sexual relationship between an “erastes” (an older man, or “lover”) and the “eromenos” (or “beloved”), was cultivated among the elite and understood as a form of mentoring. The love between Achilles and Patroclus in Homer’s Iliad was widely seen as a model of this relationship. Plato’s Symposium suggests it’s good for democracy (since the attachment between erastes and eromenos is greater than that to a despotic ruler).

Phaedrus argues: “For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning life than a virtuous lover, or to the lover than a beloved youth.” But, as with Socrates and Alcibiades, the relationship could be non-sexual and purely intellectual. The Romans were, however, not so enthusiastic about pederasty, and they gave us the foundation of our legal systems. Child sexual abuse has long been outlawed in Europe and is covered by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (which includes a protocol on child pornography).

The gesture of providing refuge and redemption to a criminal may have something to do with the university’s history as an outpost of the church. Cambridge, our second most ancient university, owes its origin to scholars fleeing persecution in Oxford in the 13th century and seeking to build an alternative, more accommodating kind of place.

Back then all colleges were, in effect, theological institutions, their scholars were monks, and they were rocked by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. Our modern academic gowns are derived from ecclesiastical robes. Every college still has its own chapel. They are vestigial churches. You can get married in most of them, for example. When I took my vows as a “Fellow”, many years ago, at King’s College, I promised to pursue “teaching, scholarship, religion and research”. Religion was still an integral part of the package and it still is – at least in terms of mentality and attitude.

In my experience, some of the worst people in the world are the ones who think they are the most virtuous

You don’t have to be a card-carrying desperado to commit crimes. In my experience, some of the worst people in the world are the ones who think they are the most virtuous and are doing the “right thing”. Which partly explains how the Catholic Church came to visit so much harm upon young people, and notably choirboys, and then do absolutely nothing about it (until recently). Except to cover it up of course (as noted in this week’s report from IICSA, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse). We are doing God’s work so we are therefore exempt from the usual rules. The law doesn’t apply to us. We are priests and operating on a higher plane.

Does Cambridge think like this? I’ve certainly run into the holier-than-thou attitude. But more pervasive is the Nietzsche-style “beyond good and evil” mentality. Cambridge is technically a charity and exempt from paying taxes: but there is a widespread sense of being exempt from the standards that are recognised in society at large. On the one hand this encourages intellectual freedom. But moral relativism implies that anything goes. Nothing is beyond the pale any more because there is no pale.

I remember being surprised when an American friend denounced Oxbridge as essentially a “gentlemen’s club”. It certainly isn’t all gentlemen. But it is very keen on gatekeepers, on inclusion and exclusion. Just as you can be “protected”, so too you can be blackballed or blacklisted, subjected to the “stab in the back”. This is how arbitrary power gets exercised, by defining and promoting insiders and briefing against outsiders.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, TS Kuhn argued that intellectual (specifically scientific) communities are driven by a “paradigm”, a framework of thought, in effect a fairly well-defined set of questions and answers that happen to prevail at any one time. Michel Foucault suggested something similar with his concept of the episteme, the underlying archaeology of knowledge, with all its myths and metaphors, that governs the collective mind.

There is no such thing as pure research in a vacuum. You need a point of departure. But sometimes the paradigm can become overly oppressive. And so long as you sign up to the paradigm, so long as you tick the boxes, and pay the appropriate dues, you can – in the eyes of academics – do no wrong. Or the gaze can be conveniently averted.

The paradigm is like an intellectual club, where you are either in or out. You’re a believer or you’re an infidel. But within that larger club there are a lot of smaller clubs, cabals or cliques, interest groups pursuing their own narrow agendas with dedication and ruthlessness. It helps to be a member of something, it almost doesn’t matter what. I resigned from my own college’s governing body over the aggressive acquisition of power by just one such interest group. I think I may have to start a club for Neo-Existentialist Surfers. It probably wouldn’t be very big. At the moment it has only one member that I know of.

Our current vice-chancellor, Stephen Toope, a Canadian professor of law, specialising in human rights, will surely be aware of the new law, passed in 2018 in the United States, the so-called “Amy, Vicky, and Andy Act”, that requires restitution to victims of child pornography from “every perpetrator who contributes to their anguish”.

The compensation is “in an amount that reflects the defendant’s relative role in the causal process that underlies the victim’s losses, but which is no less than $3,000”. Even rounding the figures of Professor M’s victims down to 1,000, he would owe, on the current legislation, around $3m, or about 50 years of his salary (but a mere fraction of the donation from Gates). Perhaps the institution that was so keen not just to employ him but then to promote him to full professor should consider footing the bill.

Every now and then I bump into my paedophile colleague. He once congratulated me on the making of a couple of short films for the university and I found myself thinking, inescapably, well, I’m amazed you liked it given that there were no naked boys in it, not even in swimming shorts.

Another time Professor M knocked on the door of my office and came in and sat down. He had been given the job of overseeing our submissions to the then research assessment exercise. I’ve taken intellectual freedom fairly seriously over the ages, and I still do, but I’d just written a 300-page book squarely in the middle of our subject area. Surely he wasn’t going to pick holes in that, was he?

Yes, he was. It was an excellent book, he agreed, but the problem was the bibliography was not quite right. “There isn’t one,” I said. “You don’t need one for this subject. There are already too many bibliographies. I’ve used a note system instead, it’s perfectly normal.”

“Ah, well, you see,” says he, “that may not be accepted by the authorities, so unfortunately we are going to have to leave it out of our submissions.”

I said something about how academics shouldn’t keep rewriting their (very rule-bound and turgid) PhDs. But what I was thinking was this: you didn’t seem to bother with bibliographies too much when you were downloading all your baby pics.

The University of Cambridge was contacted by The Independent but declined to comment

Andy Martin used to teach at the University of Cambridge. His most recent book is ‘Surf, Sweat and Tears: the Epic Life and Mysterious Death of Edward George William Omar Deerhurst’ (OR Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks