The centuries-old battle over Budweiser

It is a David versus Goliath affair that has spanned centuries, countries and courthouses. Mick O’Hare delves into the bitter history of one of the world’s most famous lagers

The Beer of Kings or the King of Beers? The difference is a big one. So big, in fact, that the arguments have ended up in courtrooms around the world. Barrooms have long been the locus of quibbles about who brews the finest beer and the arguments are subjective at best, but rarely do they end up in front of m’learned friends. However, this one has. Repeatedly. A battle has raged for more than a century over the name and origins of two lagers that share the same name. There’s Budweiser, the beer of kings and, er, Budweiser, the king of beers.

It’s a long story. And it starts in the city of České Budějovice in the south of the Czech Republic. When the region was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire the city went by the name of Budweis, a moniker that might look familiar to lager drinkers. Beers brewed in the city were known as Budweisers. Just up the road is Plzeň (known in German as Pilsen) from whence hails the term Pilsner, or pils, another style of lager. Indeed it was commonplace in centuries past for beer styles to be named after the cities in which they were first brewed. In Germany there is Kölsch from Köln and Dortmunder from Dortmund; in Britain there were Burton ales and London porters. Towns that had the right kind of water for a particular beer style thrived and Budweis was one of them – at one point in the 15th century it had 44 breweries. It was also home to the royal court brewery of Bohemia, giving rise to the sobriquet “the beer of kings”.

Now, other than small producers, only two large breweries remain in the town. But one of them, the Budějovický Pivovar, produces a beer that among aficionados is widely acclaimed as one of the world’s classic lagers and is known as Budweiser Budvar, or – especially in the Czech Republic – Budvar for short. It was first brewed in 1895 and while it can lay claim to being a genuine Budweiser from the original brewing town it cannot claim to be the oldest extant beer in the world to be called Budweiser.

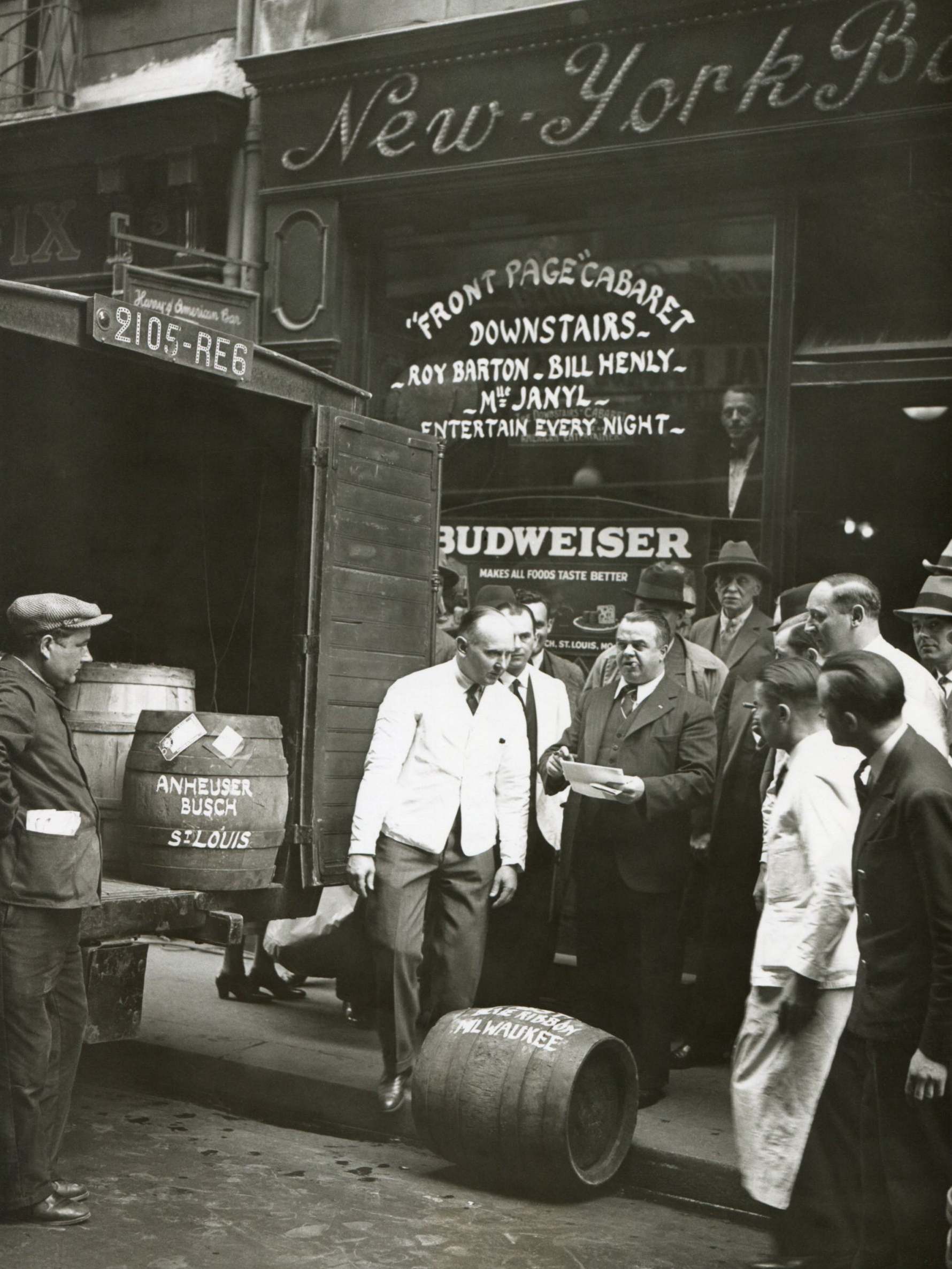

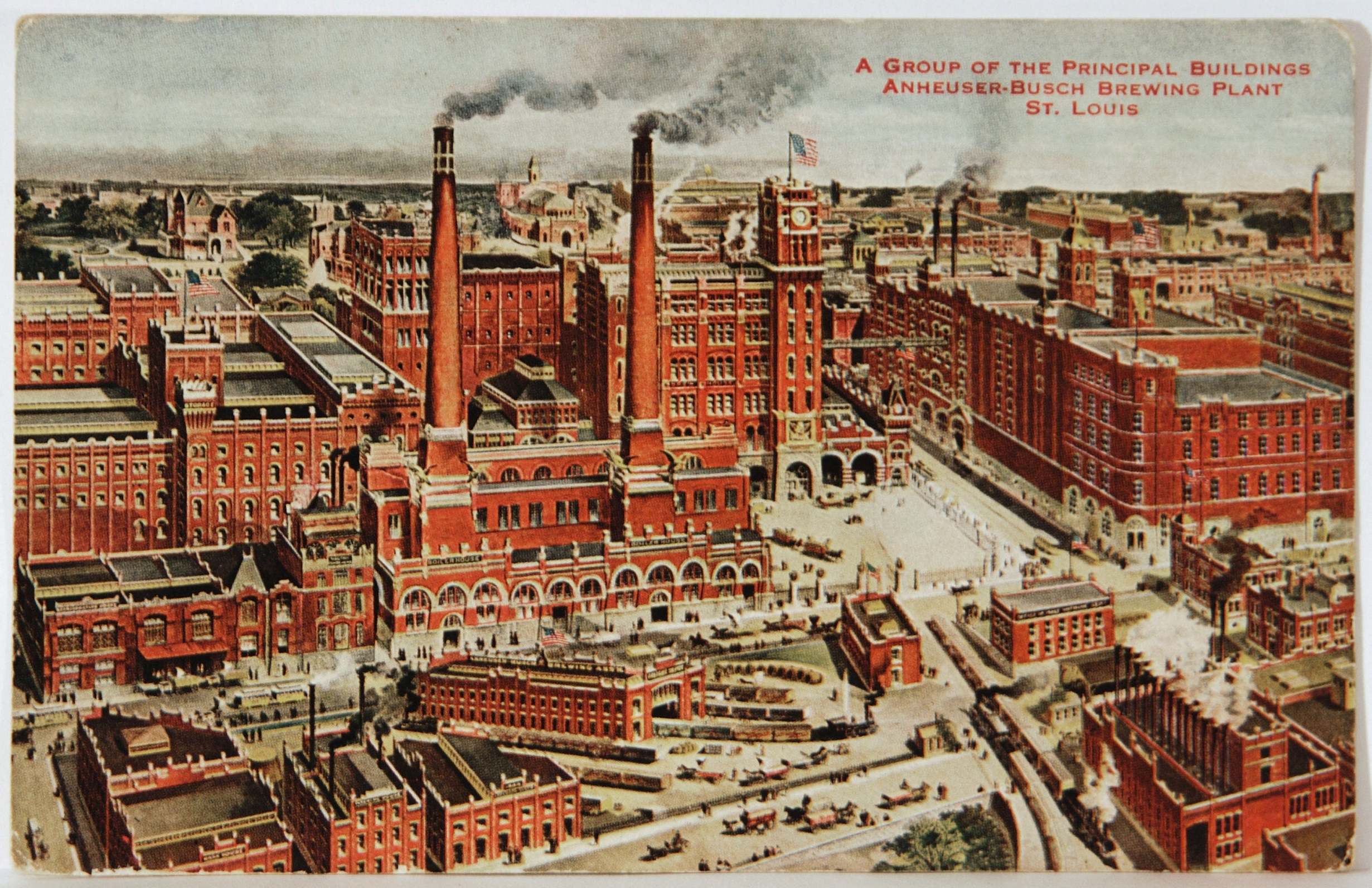

And that’s because in 1876, a full two decades before Budvar was first brewed, the American brewer Anheuser-Busch, based in St Louis, Missouri, launched a beer called Budweiser, these days often known by its nickname Bud. Anheuser-Busch, now part of the world’s largest brewing conglomerate Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV (better known as AB InBev), had cottoned on to the fact that Budweis was associated with great beer and, knowing that many of its customers were Germanic and central European immigrants, named its beer accordingly. And to add to the confusion – and a sense of knowing familiarity perhaps – labelled it “the king of beers”.

But no matter, because back in the 19th century the two beers rarely came into conflict. They served their home markets and ploughed their own grain furrows – never the twain shall meet. In 1907 they even came to an agreement that neither would market their beer in the other’s country. There was further accord in 1939 when both sides acceded that the American brewer would have the rights to the name in all territories north of Panama while the Czech brewer would have similar licence in mainland Europe. But then came the Second World War. Czechoslovakia – as it was at the time – was occupied by Nazi Germany and then, at the end of the war, came under the influence of the Soviet Union, becoming a member of the eastern European bloc of communist nations and receding behind the iron curtain. That meant everything changed. Trade agreements between former capitalist companies and nations no longer held sway – or at least that was the assumption.

Anheuser-Busch began selling its Budweiser in western Europe, but then the Berlin Wall fell, the Velvet Revolution threw off state communism in Czechoslovakia in 1989, and the Budějovický Pivovar, owned then, as it still is now, by the Czech government, decided it wanted to start exporting. In 1994 Budvar’s general director Jiří Boček opted not to sign a new trademark agreement with Anheuser-Busch. Which, in copyright terms at least, meant all hell broke loose.

AB InBev claimed precedence. Its beer was first brewed 20 years before the Czech version the company argued. But the Czechs fought back saying that a style cannot be copyrighted – their beer is a Budweiser because it is brewed sourcing local ingredients in what was Budweis (in 2004 it was granted protected geographical indication, or PGI, by the European Union) and, they point out, their rival brewery in České Budějovice, the much older Samson, had been using the term Budweiser for its beers – and exporting them – long before AB InBev. Budvar only brews its beers in České Budějovice – they do not want to compromise the terroir of their product – while AB InBev brews Bud under licence around the world.

It is a David versus Goliath affair too. AB InBev brews more beer worldwide annually than any other company, an astonishing 560 million hectolitres. It employs more than 170,000 people and, in addition to Bud, owns such worldwide brands as Stella Artois, Becks and Corona. Bud itself is the most valuable beer brand in the world while AB InBev’s sales in 2019 topped $52bn. Meanwhile, the Budějovický Pivovar brews around 1.7 million hectolitres a year (about 0.3 per cent of AB InBev’s total) and employs around 700 people.

Since 1994 the dispute has been fought country-by-country and has seen more than 100 cases brought before trademark judges. In addition to precedence and location, the arguments have been long and varied. AB InBev has pointed out that it ran advertising campaigns in many nations that predated any trademark registrations by Budvar, such as that in Italy in the 1930s, while in the same country Budvar has won a court ruling which stated that although Budweis as a name for the city of České Budějovice may no longer exist, any appellation previously applied to legacy denominations is still valid. Complicating matters is the fact that AB InBev holds some European copyrights for non-beer products such as merchandise.

Down the years the legalities have become ever more byzantine. In 2009 the European Court of First Instance ruled that AB InBev could not register its trademark in the EU, because Budvar had got there first in Austria and Germany. But conversely, British judges, later backed by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), ruled that in the UK, where AB InBev registered first but Budvar sold its beer in Britain before the AB InBev registration, the trademarks could be concurrent. The British judges determined that the beer-drinking public was well aware of the differences between the two beers and no confusion would arise. It, whether one is following the mindboggling complexities up to this point or not, was a landmark ruling.

Piers Strickland, trademark lawyer at London-based Waterfront Solicitors, hails its significance. “It’s an unusual dispute,” he says. “Most companies don’t want to waste time slugging it out for years and spending millions. But in the end it did establish an important point of law. There can be concurrent rights.” It means that Britain is the only nation in the world where both beers can be sold under the name Budweiser. AB InBev wasn’t happy. “We feel this is not the right solution as we want to make sure that when our consumers ask for a Budweiser, they receive our quality beer that is renowned for its crisp, refreshing taste and tradition of beechwood ageing,” said AB InBev’s then spokesperson Karen Couck in full corporate-speak. Nonetheless, she and her company were stymied. Whether Brexit and Britain’s departure from the strictures of the ECJ will tempt AB InBev to try to reverse the decision is unknown.

In fact, the company makes a point of proclaiming its beers are ‘fresh’ – an anomalous statement in many ways for a lager, one akin to rivals of vintage Bordeaux attempting to sell their wine on the back of the fact it was made only last week

In most cases, though, courts tended to rule on geographical lines. Budvar could be called by its original name in Europe, with the American beer being sold under the name Bud, while in North America and some parts of South America the American beer kept its full name and Budvar is sold as Czechvar.

Budvar claims to have won around 60 per cent of the cases it has fought with many others ending in a draw or agreed settlement. And at one point, in 2007, it seemed detente was on the cards: the two sides reached an agreement that stated AB InBev would market Budvar/Czechvar in the United States and several other countries for an undisclosed fee. However, both sides were adamant this did not affect any ongoing lawsuits. Unfortunately, the thawing of relations didn’t last and the partnership was terminated in 2012. Fears – rightly or wrongly – that AB InBev was using the deal as a pretext to a takeover were never far away.

Paradoxically, apart from their colour, the two beers could not be more different. And while courtroom copyright conflicts are not necessarily won on the quality of the products in dispute, Czech Budvar is widely considered to be one of the world’s great beers, with a rich malt and vanilla aroma, floral hops on the palate and with a great balance of malt. It’s the top-selling Czech beer in Britain and Germany. Aficionados aren’t so keen on the American version which uses around 40 per cent rice – in place of barley malt – and fewer hops than the Czech version leaving the beer relatively innocuous. Rice is far less flavoursome than barley malt and although the beer is matured, as Couck pointed out, on beechwood chips (an old Bavarian technique for clearing yeast from beer) opinion varies over how much this adds to the taste. However, the use of rice does allow the beer to be chilled to a low temperature for serving – around 6C – meaning that any flavour it might have is masked further. Confusingly, while claiming the style-name Budweiser, the American version is often described as a pilsner too. In reality, it can’t be both.

The word lager is taken from the German word for store and the reason it was adopted as the English name for beers such as Budvar is because a true lager should be stored in cool, dark conditions, to allow flavour to develop and round off any rough edges. Budvar is lagered for 90 days minimum. Meanwhile its American rival is lagered for less than a quarter of that time. In fact, the company makes a point of proclaiming its beers are “fresh” – an anomalous statement in many ways for a lager, one akin to rivals of vintage Bordeaux attempting to sell their wine on the back of the fact it was made only last week.

Beer writer Roger Protz, author of 300 Beers To Try Before You Die, says these technicalities make a huge difference to the outcome. “While Budvar is lagered for 90 days, American Bud has a total production cycle that lasts 21 days and ‘can be reduced at times of high demand’. The American beer lists rice before barley on the label whereas Budvar is an all-malt beer. Taste the difference!” says Protz. Nonetheless, despite the indifference of the beer cognoscenti, Bud is the best selling beer in the world (excluding China), and one of the world’s most valuable 100 brands.

But neither worldwide popularity, as in the case of Bud, nor widespread acclaim, as in the case of Budvar, wins legal battles. And there was a further twist in 2014 when the ownership of Samson, the second brewery in České Budějovice, was bought by AB InBev – a smart piece of legal chicanery intended to support the company’s claim to and usage of the Budweiser trademark. Now AB InBev owns a brewery in Budweis. “For years AB InBev has done its best to shut down or take over their Czech rivals,” says Protz. “This is just another part of their strategy. The fact they now own Samson is a serious threat. They are expanding capacity at the brewery, and it means they can use the Budweiser trademark legally in the EU.” Essentially the purchase of Samson bought AB InBev greater clout in court (or so it hopes) rather than a bunch of new beer brands.

Simon George, managing director of Budweiser Budvar UK, says that although this seemingly changes very little apart from removing one of the three parties previously able to use the trademark it does give AB InBev the capability to brew a beer to the EU’s PGI standard – that is a true “Budweiser” as defined by the PGI. “It must use the stated PGI recipe using Budějovický water and Czech raw materials,” says George. “Then it conforms to the EU definition.” But it seems unlikely that AB InBev’s Bud will ever be brewed to this specification so although George and the brewery are keeping a watchful eye, at the moment they are confident that Budvar itself is not under imminent threat. “But don’t confuse PGI denomination with the trademark. No other entity can use our brand name in the Czech Republic or wherever we already own that trademark registration,” he says.

Fortunately, and also deliberately, the Czech government never sold off Budvar even after the fall of communism and the return of the free market, in large part to protect it from the cash-laden ambitions of AB InBev. So, in the short term at least, the Czech brand is safe. Boček says: “After 25 years, I can say I made the right decision not to sign any agreement with the Americans.”

What’s Brewing, the newspaper of the Campaign for Real Ale used to describe AB InBev as a “rice brewer and international bully boy”, at least until the lawyers came calling. And while amusing, it was also – to a certain extent at least – unfair. Cases were also brought against AB InBev by Budějovický Pivovar, and where AB InBev did take its rival to court it was asserting its moral right to its brands, defending the interests of its business and its employees and using perfectly licit means to support its claims. That its protagonist was a small brewer lacking AB InBev’s influence and legal finances should have no bearing on the legitimacy or otherwise of the court proceedings.

But it’s easy to see why beer aficionados have been prepared to take sides – everyone loves an underdog, hence Budvar becoming something of a standard-bearer for the little guy; the perception – right or wrong – of the plucky, fearless defender of the Average Joe standing up to the Corporate Might Of America.

But for now, the guns have fallen silent, a rare occurrence. “There are no major legal battles at the moment,” says Boček’s successor Petr Dvorák, the chief executive of Budvar in České Budějovice, “but we know they will return whenever any party tests a ‘new’ market.” In the meantime, both companies will continue to brew their own lagers, seemingly – at least according to the courts – confusing drinkers everywhere but Britain. Well, that is until you taste them side by side… at which point you’ll know immediately if you are a beer aficionado or not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks