Bridgerton: Is this really as far as we can go in conceiving racial integration?

The frictionless racial politics of ‘Bridgerton’ stands in stark contrast to the real life of one racially mixed British princess. It should have changed the script, not just the cast, argues Antara Haldar

Once upon a time, in an alternate reality, lived a duke, the Duke of Hastings. His name was Simon Basset. Right now, in a lived reality, lives a duchess, the Duchess of Sussex. Her name is Meghan Markle. Between Netflix’s record-breaking hit series Bridgerton , which reached number one in 76 different countries, and Oprah Winfrey’s tell-all interview with Harry and Meghan, by last spring at least 150 million people had witnessed one of two royal dramas.

Even as Bridgerton returned to screens this spring for another season with historic viewership, the duke and duchess, both on-screen and off, from last season continue to dominate the conversation. Yet few have drawn the connection between the two stories of race and royalty – or dwelt on the wider import of the debates that they’ve ignited on racial politics for our everyday lives and systems of thought.

Bridgerton’s fictional Duke of Hastings, the blinding star of Season One – and judging by the reviews, the series as a whole so far – played by heartthrob Rege-Jean Page of Zimbabwean and English ancestry, is notable for his rakish good looks but, beyond his brown skin tone, he has conformed entirely to British high society – complete with the snotty southern English accent and sartorial standards that make one wonder how he makes time for anything else. The show, produced by TV mogul Shonda Rimes of Grey’s Anatomy fame, and based on the novels by Julia Quinn, is premised on the conceit that it is set in a parallel “racially integrated” universe – a type of alternate colourblind history of Regency England – and has been praised in the media for its racial diversity ie, that the non-white characters have proper roles rather than exclusively as servants or slaves.

Playing with the idea that Queen Charlotte, on whom the Queen in Bridgerton is based, may have been biracial, it follows the fates of the eight Bridgerton siblings in their quest for – multiracial – love: a sibling a season. Yet its protagonists typically display little trace of the heritage of any culture other than that of the British aristocracy (or more specifically English) even in the current, more politically correct season. Its creators are emphatic that the series is a “reimagined world” – rather than a “history lesson” or a “documentary”. But the entire artistic enterprise begs the question: is this really as far as we can go in conceiving of racial integration – even in our imaginations?

As one of the first members of the Faculty of Law from the global south at the University of Cambridge, I am acutely aware that the consequences of these portrayals of people of colour – even ones that readily confess to being light-hearted entertainment – are far from frivolous. Our top universities have a long history of educating princelings and maharanis from around the world. This was deemed an enriching experience for the occidental aristocrats that were the institution’s main clientele, adding a worldly panache, so to speak. But the terms of engagement for foreign visitors, however esteemed, seemed clear: the varied groups of international elites were but the most prized specimens of the overall “civilising mission” of the English establishment.

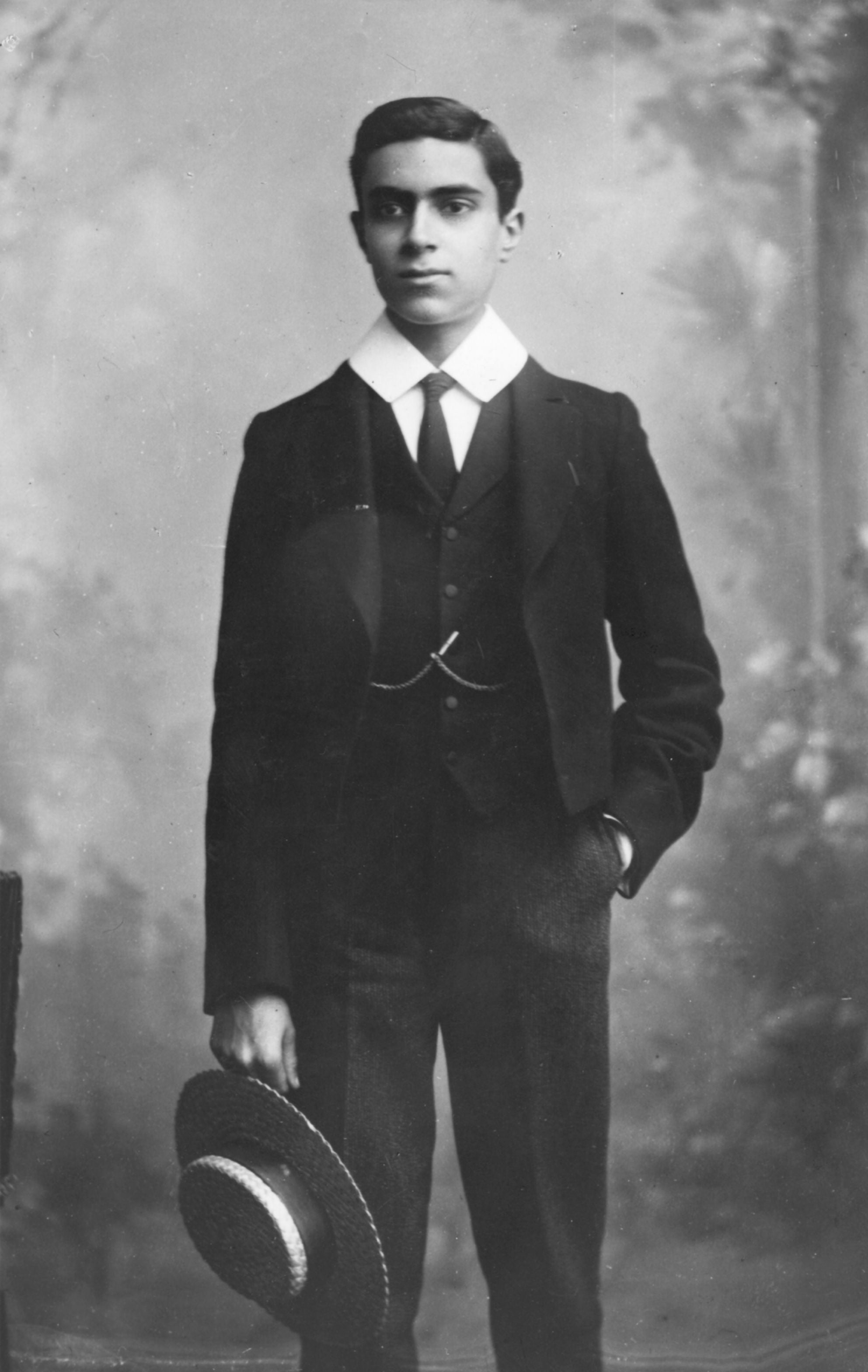

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of my own country of origin, India – whose portrait is hung with complete unselfconscious irony at the entrance to Cambridge’s arguably grandest college, Trinity, alongside that of Prince Charles – wrote about his quest to become, for all practical purposes, an Englishman during his time at Harrow and Cambridge. It was only upon becoming a mentee of Gandhi’s – who had his own flirtations with Englishness while studying for the bar in London – that “Joe’s” attentions were diverted from the seductions of Savile Row and re-focused seriously on nation-building. Bridgerton, thus, hits home particularly hard as an instance of the blurring of the lines between fact and fiction: it may be a more accurate representation of the higher echelons of English society than its American makers may realise.

The airbrushed portrayals in Bridgerton of devastatingly good-looking, fabulously rich minority ethnic characters as exemplars – deracinated, but overwhelmingly unconflicted about it – seems to be a thinly veiled brochure of the colonial mission of yore: “adopt our ways, and prosperity will be yours!”

By extolling the ways of speaking, dressing – and particularly thinking – that have been the preserve of the privileged, geographically and socially, it delegitimises and stigmatises other ways of being. In both of these cases, the process at play is not one of building a robust multiculturalism or cosmopolitanism, but rather one of aggrandising assimilation. Many colours, if one must, but one culture, exclusively. It gets the points for improved optics while, as post-colonial theorists would say, subalternising all the same: placing all “other” cultures in a position of implicit, sometimes explicit, inferiority to the colonising one.

Indeed, the frictionless racial politics of Bridgerton stands in stark contrast to the reality of the lived experience of the most high-profile of real-life racially mixed British princesses. Recall, as a poignant instance, Meghan Markle’s tights debacle(s): on one occasion she was, allegedly, urged by palace staff to wear tights entirely unsuited to her skin tone, while, on another, she is reported in to have had to battle her sister-in-law, and custodian of English propriety, Kate Middleton, as she tried to emancipate her bridesmaids from them.

To this end, the portrayal of a wider array of ethnicities on screen and stage is – when not mindlessly perpetuating racial stereotypes, like Apu from ‘The Simpsons’ – a good thing

In a similar vein, it was hard to miss the awkwardness of several of her public appearances in which her lustrous – already-straightened – black locks were straightjacketed by a severe-looking fascinator while she attempted to wave like a true royal. As the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche has noted hair, particularly “black hair”, much like skin colour is resonant with symbolism. These might seem like trivial instances, but so great was the dissonance unleashed by the pressures of assimilating and the loss of voice that the cumulative toll it took perhaps led to her and Prince Harry making the decision to, for all effects and purposes, break with the royal family. By comparison, the fictional Duke of Hastings had internalised the English way so completely that he never invited even the slightest comment.

That is not to say that any non-white character, on celluloid or otherwise, must be defined by race. The point is, rather, that the making of a series like Bridgerton provides the opportunity, as a thought-experiment, to explore more fully what an alternative trajectory might have looked like; much as Meghan Markle’s entry into the royal family provided an opportunity for it to revisit and modernise its norms and redefine what British royalty was.

But surely, in both cases, this should have involved some give and take? Some compromise – even learning – on both sides, rather than the apparent cultural conquest of one group by another. Not just some ceremonial kente cloth in the background or a black cellist at the royal wedding in 2018, but a deeper engagement in which the tryst yields the fruits of genuine multicultural engagement: for example, a Queen who governs with deference to not only English values but the humanistic tradition of ubuntu in African philosophy in the case of Bridgerton, or a royal family that actively embraced young Archie’s multi-ethnic origins as a proud emblem of changing times, and progress, in the case of real-life Britain.

In life and art, the chance was missed to see the changing cast of characters as a shot at a new, better narrative. A post-racial utopia, in 1813 or 2013, is one where the whole is more than the sum of its parts, rather than one in which an array of diverse entities is simply shoehorned into the existent frame; a shifting of the paradigm, rather than a tenuous stretching of the old one to reluctantly accommodate new elements.

While every serious academically inclined US law school has at least a course or two on race, here in the UK we have tended to erase our own history. Generations of students, particularly from the Commonwealth, came and went without so much as an explanation of how they came to acquire their legal inheritance – let alone being invited into a dialogue about how to shape its future. Yet, even when such a course was ultimately introduced, knowledge about, or gleaned from, non-European sources seemed to me to be treated as peripheral: a frill at best, a politically motivated intrusion at worst.

As long as integration, inclusivity or diversity is restricted to simply permitting a wider range of racial players to enter the arena while keeping the rules of the game in place – whatever the arena – the system of apartheid at the heart of racial inequality will persist where it matters most: in our thoughts. But we can do better, the game can be changed. The critical legal scholar Boaventura de Sousa Santos at the University of Coimbra talks about “epistemic justice”. The notion that a plurality of experiences and the ideas – yes, even from the global south – should be considered a legitimate source for constituting what is called, in the academy, the canon: the theoretical frames that shape the organisation of knowledge. This is true of the academy, screenwriting or, even for that matter, royalty. We can, he argues, cherry-pick from the gamut of available options to create the most emancipatory possible world.

A well-written character, by definition, brings their agency to bear upon their circumstances, but the non-white characters in this season are shaped entirely by their environment

To this end, the portrayal of a wider array of ethnicities on screen and stage is – when not mindlessly perpetuating racial stereotypes – like Apu from The Simpsons – a good thing: allowing audiences to see people “like them” represented for the first time ever and roles to those with profiles who were previously denied. But this approach risks being, optimistically, lazy and, pessimistically, self-defeating, giving both makers and consumers of art a false sense of dispensing with their moral duty while leaving core prejudices in place. The superior approach is to either lend voices to those who were silenced before or, better still, inject completely new points of view into the conversation. A slew of recent films like Crazy Rich Asians, Black Panther, Get Out, Encanto or, most recently, Turning Red tell stories that didn’t get told before. But the process can go even further: by truly mainstreaming once-marginalised perspectives.

When Jon Stewart announced he was stepping down, American TV producer Jen Flanz of The Daily Show did something that had been, until then, unthinkable: inverting the gaze. Instead of replacing Stewart with one of the many established US comedians jostling for the position, she opted to get a fresh, new voice from the global south as a commentator on the daily news in the US, the South African comedian, Trevor Noah. Lin Manuel Miranda’s smash-hit Hamilton didn’t just switch up the shade card of the cast members but reinterpreted the story of America through a nuanced racial lens. The Oscar win in 2020 for Korean-language film Parasite, by director Bong Joon-ho, powerfully demonstrated the universality of themes of social inequality and the prowess of film as a global medium.

The “ethnic” component of season one of Bridgerton was largely ambiguously black, while the flavour of season two is South Asian. The characters seem a bit more in touch with their roots. The female lead, oddly named Kate Sharma, for instance, breaks into the occasional violently accented “Hindustani” (a language as fictional as a racially integrated Regency England), there is talk of sitar-playing, a preference for chai over the more tepid English version of tea, a traditional sisterly Indian head massage and even a Haldi ceremony, a traditional Hindu pre-wedding ritual (albeit here a suspiciously and atypically clandestine one).

The characters are, however, rendered palatable by dint of European first names like Mary and Edwina, while the family conspicuously mispronounces its own surname (to say nothing of the legendary Urdu poet, Ghalib). Even more fundamentally, the cultural references are restricted to origin rather than having any bearing on future direction. A well-written character, by definition, brings their agency to bear upon their circumstances, but the non-white characters in this season are shaped entirely by their environment while playing virtually no role in sculpting it. The truth of the matter is that the diversity of the current season remains, quite literally, skin deep. At the core, this season, too appears to be engineered for the white gaze.

The world of fiction is the space where we can explore, and experiment, with different approaches to the syntax of a new society: one that does justice to the kaleidoscopic realities of the globalised world we live in. But, at the end of the day, the “multihued, multiethnic, colourful world” that the creators of Bridgerton tout has the depth of a billboard for United Colors of Benetton clothing. More an aesthetic choice – a colour scheme – than a shift in the storyline. The fact is that, unless the institutional frames change at the core, we are likely to face a series of racial ruptures that will render more than the royal family obsolete.

Changing the narrative requires not just a wider colour palate of characters in the cast but the openness to different systems of thought, a different script, if you will. But the first step to creating a better reality is to dream it up, and the limit to the process is often, as Bridgerton illustrates, our imagination. What is at stake is what it means to be British.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments