Food labelling rules will be lost post-Brexit... but who actually cares?

Once we leave the EU at the end of the year, anyone anywhere can make a Cornish pasty, a Cumberland sausage or a Melton Mowbray pork pie. But what’s in a name, anyway, writes Andy Martin

I jotted it down on my shopping list (on my phone): “milk”. When I hit the aisle in M&S though, I realised: maybe I should be fined or locked up or whatever for writing that down, because I wasn’t buying “milk” at all. I should really have written “oat drink” or possibly “almond drink” or “coconut drink” – a plant-based alternative to food for baby cows. My feeling is that the calves need their mother’s udders more than I do. Meanwhile, I am not allowed to refer to alternative forms of milk as “milk”. On pain of some kind of immense bureaucratic finger-wagging at me.

The great question of whether or not you can call a veggie burger a “veggie burger” is similarly in play. We are entering a new age of rampant lexicon control. And behind the thought police are the shadowy fat cats who rule over the meat and dairy industries. When Winston Smith, in 1984, was given the job of tightening up, reforming and cutting down on people’s vocabulary with a view to enslaving them, it was all about the dire influence of communism. But Orwell got it wrong: capitalism can be just as bad when it comes to clamping down on language and brainwashing us. The corporate mind is scared of the freewheeling use of such dangerous words as “milk”.

For once, the great land of the free might really be more permissive in this department. My good friend Robert Friedin, Princeton professor and author of the recent Adventures in English Syntax, tells me that he can go down to his local store in Princeton and buy “coconut milk” and, should he wish to, oat milk and soy milk and almond milk. He has a whole spectrum of milks at his disposal. He also points out that Princeton menus regularly feature “veggie burger”.

According to the Book of Genesis, it was Adam who first gave names to every beast of the field and every fowl of the air: “and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.” He left out milk though. Then he messed it all up by eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge. After that Tower of Babel blew up and we were left with the anarchy of languages and unlimited naming.

Pointing to something and giving it a name (technically, “ostensive definition”) is one of our most fundamental gestures. All parents do it for their children: “Look! It’s a duck.” Builders do it: “Look! You’ve got damp.” Doctors do it standing in front of X-rays: “Look! That’s a tumour.”

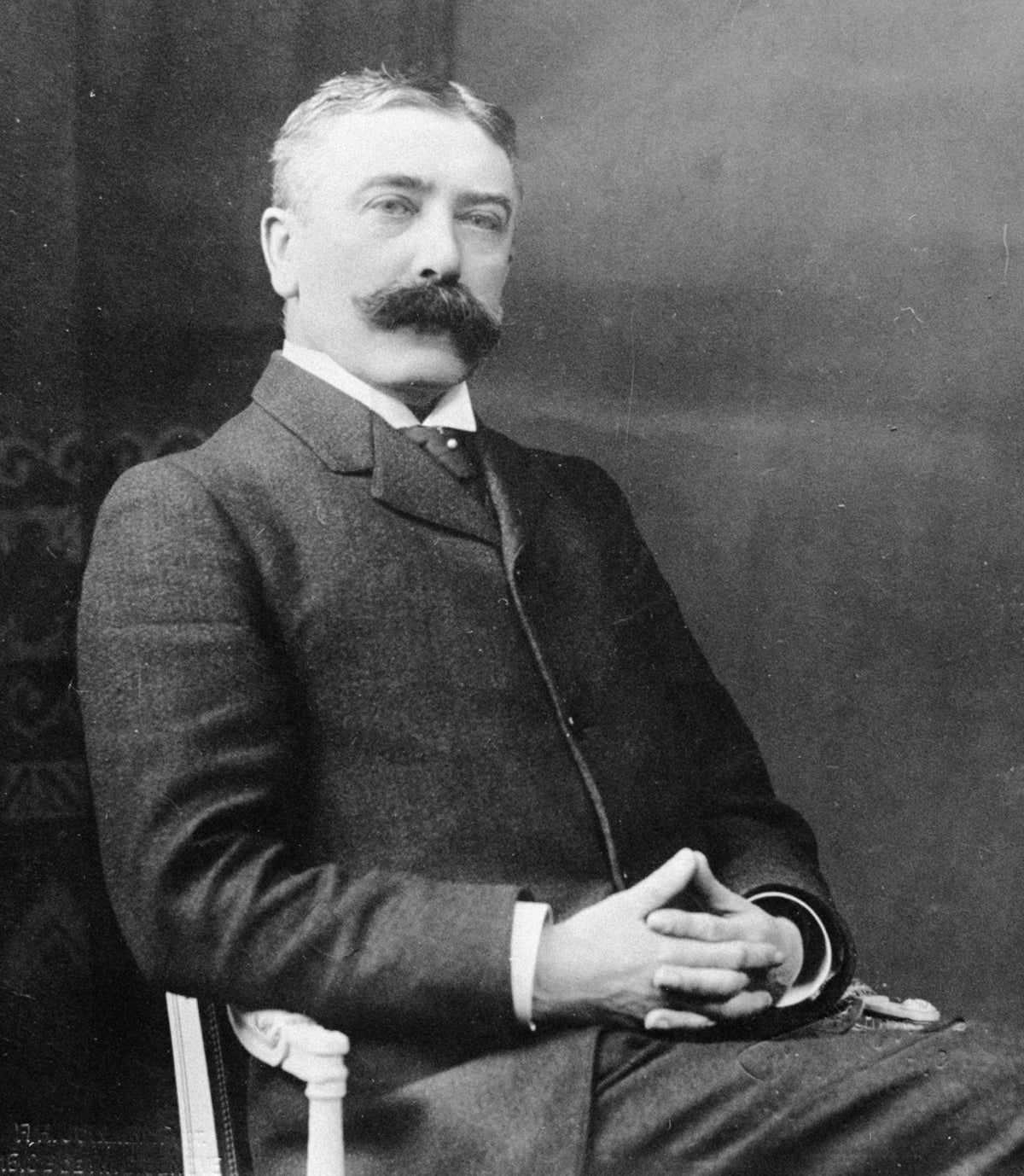

The great Swiss linguistician Ferdinand de Saussure pointed out that there is no divine right in language and the connection between the “signifier” (the physical word) and the “signified” (the thing referred to) is arbitrary: there is no necessary relationship between, for example, “cat” and the furry domesticated quadruped that chases mice. It may have been in part some qualm about this quality of language that persuaded Bertrand Russell that he should not say “there is a dog” but rather, to be more exact, “I see a canoid patch of colour”. It looks like a dog, but I could be wrong. We have to be careful about naming anything.

All of which is fair and reasonable. For example, certain parents really ought be more careful about naming their children. In New Zealand, judges disapproved of naming a baby girl “Talula Does The Hula From Hawaii” (and allowed her to change her name). Other potential names that likewise bit the dust were “Anal”, “Fish and Chips” and “Number 16 Bus Shelter”. A pair of twins were spared the indignity of “Benson” and “Hedges”. The idea was to protect these poor kids from future derision. It was thought that the names “Queen Victoria” and “Lucifer” had probably already been taken. But do we need to spare certain kinds of food or beverages embarrassment?

Part of the problem with capitalism is that it has given rise to the idea that somebody owns everything. Including words. Look at what happened to champagne, for example. Champagne is of course a sparkling wine associated with a specific region of France (that some bright spark way back when happened, in an arbitrary way, to christen “Champagne” – possibly named after the Campania area in Italy, an extension of the word “champ” or “campo”, field). The first champagne of the kind you might want to drink was probably an accident but it turned into a full-scale industry in the 19th century. The main problem then was exploding bottles. It was inevitable that the Champagne winemaking community would ultimately seek to codify and claim ownership of their effervescent style of wine.

So all other kinds of sparkling wine are now just “sparkling wine”. For a while at least the village of Champagne in Switzerland got away with marketing a “Champagne” that was not even sparkling, until the EU got involved. Even the term “méthode champenoise”, or “champagne method”, has been banned under EU law. On the other hand I’m just as happy to knock back a bottle of prosecco or cava as a Moët & Chandon or (James Bond’s favourite) a Bollinger. Brands have taken over from mere names.

It’s interesting that the French have an Institut National des Appellations d’Origine. Maybe it’s not so surprising that it renamed itself the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité. And talking of France, the French are always striving to get rid of illegal linguistic immigrants such as “le parking” or “le rugbyman”, generally in vain. An old friend of mine once headed up a committee in Paris whose mission was to abolish “le hotdog” (only the name rather than the sausage in a bun slathered in sauce). After several years consultation and, I like to imagine, liberal quaffing of champagne, they finally came up with “saucipain” (from “saucisson” for sausage and “pain”, bread). Brilliant but, sadly, no hotdog sellers ever took a blind bit of notice.

So far as I know no one has yet tried to copyright “water” or “air”. Maybe it will come. But meanwhile “milk” is another matter, as Oatly discovered. It was the Swedes – scientists working at the University of Lund – who first worked out that most people around the world are actually lactose intolerant. Siphoning off the liquid produced by cows to feed their young was a weird western European perversion. Oatly, as the name suggests, was the first to come up with an alternative, plant-based form of milk, suitable for vegetarians and vegans or anyone else, cunningly extracted from oats.

But back in 2014 the brand was sued by the Swedish dairy industry. Its use of the word milk was, according to the prosecution, “misleading people” and “scaring them into thinking cow’s milk is dangerous”. Oatly argued that it had no intention to mislead. It merely wanted to draw people’s attention to more sustainable plant-based options. And stop baby cows being deprived of baby cow food. I definitely agree about the “sustainable”. Cows produce not just milk but an awful lot of methane. According to some helpful BBC statistics, a quarter of global emissions come from food; half of food emissions come from animal products; and half of all farmed animal emissions come from cows and sheep.

Part of the problem with capitalism is that it has given rise to the idea that somebody owns everything. Including words

Oatly can’t even say it’s “like” milk. Similes are banned. In the latest twist in the Oatly saga, the European Trademark Office (EUIPO) recently prohibited them from using their own slogan, “It’s Like Milk But Made For Humans”. The EUIPO argues that there is “nothing thought-provoking or surprising” in this sentence that it can see. Seemingly taking the exact opposite tack to the Swedish dairy industry, it said that “there is a belief in society today that milk is not good for the human body” and that “the average consumer will be aware that despite being widely consumed by humans, the intrinsic purpose of milk originating from animals is to feed their young”.

Oatly is appealing. Its press office says: “We are now as confused as you probably are. After all, we’re pretty sure our job isn’t done yet. Does the ‘average consumer’ (whoever that is) really believe that milk is not good for their body and is only meant for baby cows?”

The government doesn’t think like that, for one. A recent advertising campaign, called “Milk Your Moments”, was funded not only by Dairy UK but by Defra and the Scottish and Welsh governments. And Mind, together with the Scottish Association for Mental Health. They say milk is good for mental health, when you share a coffee or an ice-cream (as one used to): “Milk is often there in our moments of connection.”

But I think my mental health is being affected by not being able to use the word “milk” when I want to. If you pour it on your cornflakes I think it should be called milk. Fortunately I can still order a veggie “burger” if I feel like it. But whether I can or not has been decided in Brussels. Following on from the dairy industry attack on vegan milk producers, a group of meat farmers tried to bring in a measure that would ban vegetarian products from being called “sausages” or “burgers” on the basis that these words would be “misleading” people into thinking the products contain meat. You’d think it was obvious that anyone eyeing up a veggie burger is clearly not interested in gorging themselves on meat. The clue is in the word “veggie”. Vegan burger producers were desperately scrambling for alternatives. Disc? Tube? Fortunately the ban was thrown out.

Not so where milk is concerned though. The European parliament has got it in for vegan milk alternatives. An obscure annex (Part III of Annex VII to be specific) in Regulation (EU) No 1308/2018 (Regulation), Article 78, concerned with terminology and naming conventions, states that the terms “milk”, “cheese”, “yoghurt”, “butter” or “whey” can only be used in association with products that contain dairy “milk” (which is defined as “…the normal mammary secretion obtained from one or more milkings without either addition thereto or extraction therefrom”). In a vote in October, MEPs voted for Amendment 171, which amends Annex III to further ban phrases like “vegan cheese” as well as “butter-style”, “yogurt-style” and “cheese-style” for dairy-free products. Henceforth, plant-based alternatives will just have to be known as “plant-based alternatives”.

To be honest, it seems to me inconsistent that they then voted against outlawing the use of “steak”, “sausage”, “escalope”, “burger” or “hamburger” by non-carnivores. What was wrong with you, meat industry guys? I am reminded of the shrewd remark of a barman in Marseille who was complaining about Marseille Olympique who had recently been fined and chucked out of the European Cup on account of corruption. “It was terrible,” he said. “We weren’t paying enough! We tried to do it on the cheap.” In the end, the European parliament agreed with my Princeton friend Professor Freidin, who says “the term burger (short for hamburger) can also be appropriated for other ingredients aside from what it originally designated”.

The European Dairy Association is laughing though: “Non-dairy products cannot hijack our dairy terms and well-deserved reputation of excellence in milk and dairy.” It’s a miracle they still allow “peanut butter” – shouldn’t that be “peanut spread”? Meanwhile Amendment 171 is a slap in the face for the European Green Deal objectives and the “Farm-to-Fork Strategy”, which aim to create healthier and more sustainable food. Cecilia McAleavey, Oatly’s Director of Sustainable Eating and Public Affairs, points out that now they can’t even write “does not contain milk” on their packaging because the phrase does actually contain the word “milk”.

So long as we remain in the EU (even in a transitional state) Cornish pasties have so-called “Protected Geographical Indication” status in Europe. Not only must Cornish pasties be altogether too meaty for my taste, but they have to be prepared in Cornwall: not necessarily baked there, but only prepared. Post-Brexit, they can be prepared in Devon or anywhere else presumably. In any case the Devonians have long argued it’s theirs anyway and the Cornish stole it from them. Melton Mowbray pork pies watch out. And Cumberland sausages. In future those names will be just a nostalgic allusion.

Maybe it’s all pork pies anyway. “Milk” isn’t (or shouldn’t be) a trademark – it’s a generic term, no more specific than cat or dog. Where’s it going to stop? If the European Rose Producers Association has its way, in future productions of Shakespeare, Juliet will say to Romeo: “What’s in a name? That which we call a thorny often red flower/By any other name would smell as sweet.” Presumably if bulls could organise themselves into a parliament, they might protest about the purloining of the word “bullshit”.

Language is not a virus. We don’t need a linguistic lockdown. I say, let it rip. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, not the naming.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks