Does the Conservative Party even know what it is for any more?

Historically, Conservatism was built on four pillars, says Victor Hill in new book ‘Will the Tory Party Ever Be the Same?’ – but they have been eroded thanks to the EU

What is the Conservative Party for?

That is the question that successive generations of Tory leaders have had to confront since the party first emerged as a coherent entity under Sir Robert Peel in the 1840s. That was in the aftermath of the Great Reform Act of 1832 which expanded suffrage for the first time and the internecine animosity precipitated by the repeal of the Corn Laws.

From the first, the Conservative Party was an alliance of mutual interests between very different social groups. The aristocracy, inspired by a past that made them landed, joined forces with the merchant class who foresaw a moneyed future. Together, they could propel the economic and social changes demanded by the coming of the railways, the emergence of (what we would call) consumerism, the displacement of populations from the countryside to the towns, and the rise of Empire.

The four pillars of Conservatism

In time, the ranks of the merchant classes were swelled by what Lenin called the “aristocracy of labour” – the aspirant, upwardly mobile section of the working classes who gained property as the 19th century proceeded. Disraeli expanded the franchise to include these people. Mrs Thatcher specifically reached out to them much later with her notions of property-owning democracy and popular capitalism.

This sometimes fragile alliance always rested on at least four pillars.

The first was the prosperity of the nation – what we would call “the economy”. Conservatives have always believed that wealth is generated by private businesses rather than by state-sponsored investment. Very few people (except Marxists) talked about capitalism in the 19th century – most successful capitalists sought to become faux aristocrats.

Capitalists only came to describe themselves as capitalists much later. Long before his controversial (or infamous – depending on your point of view) “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968, Enoch Powell, in one of his essays, wrote that the Conservative Party was the party of capitalism. “When I think of millionaires,” wrote Powell, “I smile.”

Even today, few British millionaires describe themselves as capitalists. But the notion that people should be allowed, even encouraged, to take risks by setting up businesses and thereby generating wealth is supported by virtually all Tory voters, and not just rich ones. The corollary to that is, while virtually all Tories recognise that the state needs to harvest a judicious amount of tax to finance social goods, taxes should not be so high as to impede private business. Tories aspire to low taxes (though just how much spending is appropriate is a much more nuanced problem).

The second pillar was love of nation – and increasingly the British nation rather than just the English one. This has manifested itself in various forms over time – patriotism, nationalism, imperialism. This is not the place to define how each of those concepts differ. Patriotism is now socially acceptable (just); but nationalism is generally considered obnoxious (unless it is Scottish, Welsh or Irish nationalism, in which case it must be respected). Imperialism, according to the prevailing orthodoxy, was a historic crime – one for which reparations are still pending.

Of course, the Tories never had a monopoly on patriotism. White working-class Labour voters were also self-proclaimed patriots – until quite recently. But the Tories took pride in a nation that stood tall among others, had strong armed forces and a prestigious monarchy.

We have obviously moved well beyond Lord Beveridge’s safety net – some people spend their entire lives on one form of welfare or another. Modern Conservatives have found it difficult to have this conversation – possibly for fear of being demonised by prevailing leftist orthodoxy on welfare economics.

The third pillar was an aspiration to social betterment. Disraeli decreed that the aim of the party was the amelioration of the condition of the people. This implies a high value being placed on education, including self-education. The School Boards of the 1860s were strongly supported by the Tories, as was the groundbreaking Education Act of 1944.

Tories have tended to assume that people are born with unequal talents and that those with specific talents should be nurtured accordingly. They deeply resent the socialist notion that everyone should be treated the same because they are the same. Tories are deeply attached to the idea of social mobility – that is why no true Tory is a snob.

Of course life is unfair – or so Tories have believed. At the same time, there should be a safety net for those at the bottom end. Over the last 175 years Tories have increasingly acquiesced in more state intervention to support the less fortunate – successively giving full backing to the welfare state and the National Health Service. Though some of us (we are sometimes derided as reactionaries) have questioned just how much of the national cake the welfare state and the NHS should consume.

We have obviously moved well beyond Lord Beveridge’s safety net – into a realm where some people spend their entire lives on one form of welfare or another. (Housing benefit alone now costs more than the royal navy). Modern Conservatives have found it very difficult to have this conversation – possibly for fear of being demonised by prevailing leftist orthodoxy on welfare economics.

The fourth pillar was always freedom – interpreted in a very British sense of that idea. People are individuals under the law before they are citizens. The state has no business telling people what to do unless it has very good reason to do so.

This strain of individualism has always been in tension with a strain of social conservatism which has always been present in the Tory psyche – sometimes with bizarre results. Apparently, many Tories thought the state had the right to determine what consenting adults do in the privacy of their bedrooms even after 1968.

An alliance eroded

Britain emerged from the Second World War in 1945 as a demoted power – but that did not become fully apparent until 1956. Thereafter, the British Empire was dismantled in a kind of closing-down sale. (Even nations, like Malta, which petitioned to become an integral part of the UK, were rebuffed and told they’d be better off on their own). That, in turn, was followed by a period of extreme economic inertia as a resurgent Germany (funded by American largesse in the form of the Marshall Plan) increasingly made inroads into British markets.

When Britain joined the EEC (as it then was) on 1 January 1973 it was commonly known on the continent as “the sick man of Europe”. More than 70 per cent of our export trade was with the EEC 8 (it’s down to 47 per cent now with the EU 27); France was growing at nearly 10 per cent per annum while we were all but going backwards. We were coerced into the European project at a moment of extreme weakness.

My thesis is that gradually, over time, Britain’s membership of the EEC-EU eroded – and has all but withered – the four pillars on which the grand social alliance that is the British Conservative Party stands. But, of course, that grand social alliance is no longer one between the landed aristocracy and the merchant class – British society has moved on and would be unrecognisable to Sir Robert Peel.

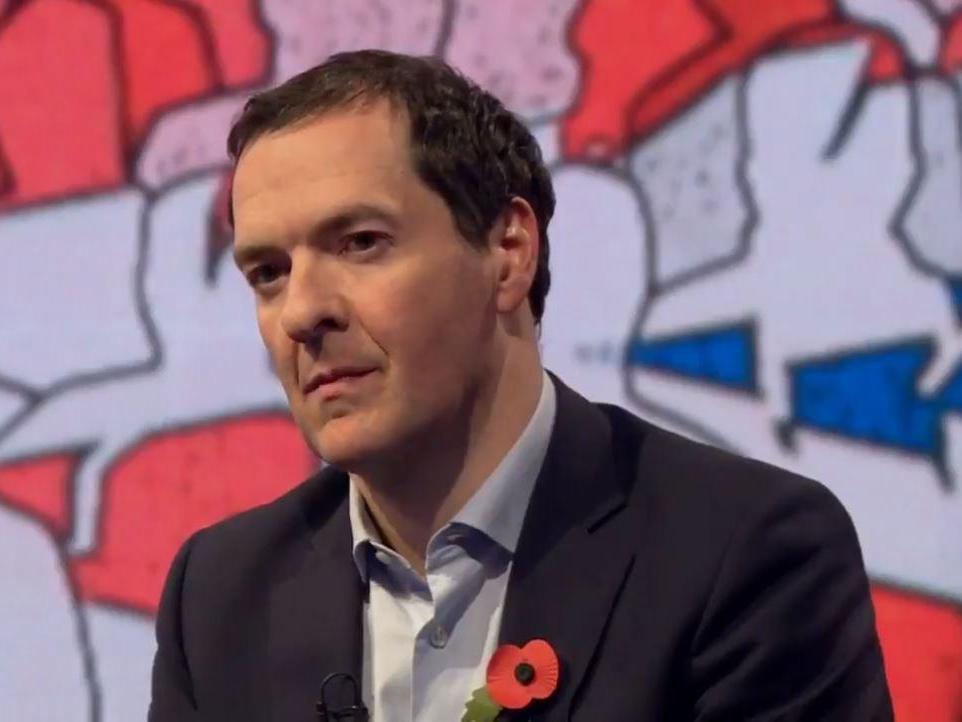

The modern Tory aristocracy is a curious aggregation of the city-dwelling (all right, metropolitan – meaning London-based) elite: much of the City; the CBI (which I am on record as describing as “a lunch club for fat and lonely people”), a small bien-pensant corner of the BBC; a faction within the Anglican Synod; people who work for media organisations owned by Rupert Murdoch; numerous tax-exile pop stars; and (to borrow from Disraeli) the row of defunct volcanoes who pass for party elders – Sir John Major, Lord Heseltine, Sir Oliver Letwin, Ken Clarke, George Osborne.

The merchant class and its aspirant fellow travellers are, pretty much, everyone else who hates Corbyn’s Labour and, increasingly, the EU elite. (And who would rather have an appendectomy than vote Liberal Democrat, Green or for the Independent Group [Change UK]. And by the way, would only vote Ukip while wearing a gas mask.) These people (with whom I identify) are finding it increasingly difficult even to engage the new Tory aristocracy at all.

How could the EU bacillus have infected the Tory corpus so pathologically?

First pillar. The EU is inherently anti-capitalist (and anti-American – even though France and Germany have had their defences subsidised by the USA for nearly 75 years). It is pro-regulation and instinctively pro-tax. It believes, in common with many European states, that most good things arise from state spending. It crushes entrepreneurship. It suffers from outrageous levels of unemployment because it fervidly resists a UK-style flexible labour market. It has created a currency union embracing nations with very differing economic structures, thus imposing wholesale deflation on the trade deficit nations of southern Europe with massively deleterious economic and social consequences. In real terms, Italians are less well off than they were in 1999.

Second pillar. It is increasingly evident that the long-term objective of the EU elite is to create a United States of Europe (of some description) which would entirely complete the process of extinguishing national sovereignty among EU members, which has been in train since 1958. If I were Croatian, I would probably think this a good wheeze (though I might remember that Germany was not such a beneficent overlord in 1941-45). Being British, I cannot see any reason to throw away a thousand years of common law which has served my ancestors well in exchange for a slightly cheaper (diesel-powered!) Mercedes.

Third pillar. The EU has undermined the very notion of citizenship. A Polish worker arriving in the UK in the years after 2003 was accorded exactly the same rights and benefits as a true-born Englishman who had paid tax all his life. One reason why social mobility has seized up is that mass low-skilled immigration drove down wages at the bottom end, thus forcing locally born people onto welfare and choking aspiration. Educational attainment among the white English working classes (especially males) has actually gone backwards. The skills gap between the haves and have-nots is still widening. Apprenticeships have declined while local aspirant students have to compete with foreign applicants for university places.

Fourth pillar. As for freedom and democracy – merchant Tories believe that the political class of both colours decided that it was more expedient to outsource decision-making and law-making powers to a remote supra-national bureaucracy than undertake those tasks itself. This outsourcing of sovereignty was underpinned by a surrender of judicial self-determination to a foreign court. They regard the EU as undemocratic, insensitive to public opinion, unaccountable – and often corrupt. It does not even assure rising living standards as once it did. But apparently the new Tory aristocracy doesn’t see it that way.

When Surgeon Cameron set out to operate on his patient from 2006 he did not imagine that he would end up killing him.

Since the defection of three Conservative MPs to the so-called Independent Group in February, thus consigning themselves to political oblivion, it has become apparent that many Tory members elected in 2010 are not only not capitalists but are not even patriots.

When the Berlin Wall fell (1989) and then the Soviet Union dissolved overnight (Christmas 1991) it seemed that liberal democracy based on private ownership of the means of production had triumphed – once and for all

One problem stems from Mr Cameron’s programme to detoxify the Conservative Party by making it a no-go zone for true-blues. (Wasn’t it Ms May who described the Tory party as “the nasty party”? – in a superb example of falling for your enemy’s propaganda.) When you advertise in a job description that “only nice, caring people need apply” – do not be surprised if you get a rush of second-rate applicants with no ideological lodestone except self-interest.

The A-listers parachuted in by Central Office to take safe Conservative seats in the years leading up to 2010 were overwhelmingly media-savvy, ever-emoting liberals who had never served on a Neighbourhood Watch, let alone done national service. The result has been effusively displayed in Ms May’s long day’s journey into night that passed for her Brexit negotiations. They proved both spectacularly disloyal to their leader while at the same time extraordinarily confused about their strategy for the nation – apart from the necessity to remain the right side of nice (a customs union). Opposing no deal outright was entirely illogical because that was the default outcome of not having a (despicable) withdrawal agreement.

One thing we can look forward to now is an entertaining Peasant’s Revolt as Conservative Constituency Associations round on the Remain-inclined MPs who made an impossible situation intractable.

Is this the triumph of liberal democracy

I would not take pleasure in telling Dominic Grieve MP just why I think his determination to reverse the referendum result was arrogant and wrong-headed. I know that he is a principled, scrupulous, thinking man – a gentleman – a linguist and a man of culture with a deep attachment to the law. In many ways he is admirable: but he is absolutely not the future of the Tory party; and, if ever I have the chance, I will tell him to his face that, post-Brexit, he has no place in this tribe.

When the Berlin Wall fell (1989) and then the Soviet Union dissolved overnight (Christmas 1991) it seemed that liberal democracy based on private ownership of the means of production had triumphed – once and for all. The Tories thought their claim to be the natural party of government had been vindicated – even though Mrs Thatcher was deposed by a pro-European cabal in November 1990. But John Major was succeeded by Tony Blair after nearly seven years of Tory rancour over European policy.

Three things undid the Major-Blair consensus over the following two decades: the infamy of the Iraq War of 2003 and its aftermath (which the Tories supported and for which they have never apologised); the financial crisis of 2008-09 (which they have never tried to explain); and the creeping realisation, especially amongst the young, that man-made climate change is a latent menace (for which Tories have no solution). The millennials are now millenarians; as such they are very likely lost to the Tory party. Therefore, a Tory future is uncertain.

But what has changed us most is the impact of globalism, as much in its digital as industrial forms. This has facilitated the rise of the super-rich, many of whom are trans-national. We mere merchants worry about freedom of capital (relocate to the most efficacious tax haven); and freedom of labour (a tide of economic migrants posing as refugees) – but we know that no one in power is listening.

Going back to Powell, when I think of billionaires, I don’t smile.

Yet I’m still a Tory – perhaps because I delude myself that I know what the Conservative Party is for.

Victor Hill is a financial economist, consultant, trainer and writer, with extensive experience in commercial and investment banking and fund management. His career includes stints at JP Morgan, Argyll Investment Management and World Bank IFC

This essay is extracted from ‘Will the Tory Party Ever Be the Same?’ edited by Paul Davies, John Mair and Neil Fowler, published by Bite-Sized Books and also available from Amazon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks