Time Out of Mind at 25 – The Reinvention of Bob Dylan

When ‘Time Out of Mind’ was released 25 years ago, Bob Dylan would reignite his career by returning to the music that had first fired his youthful imagination, writes Sean T Smith

In October 1997, Bob Dylan was 56 years old and in danger of becoming a legacy act. There hadn’t been an indisputably great Dylan album since the mid-1970s and he was widely regarded as a magnificent hurricane that had blown itself out.

But when Time out of Mind was released, Dylan would confound his critics with an astonishing return to form. The double album won three Grammies and sparked the start of a late, great resurgence in his career.

Time Out of Mind was all the more remarkable because, for some time, Dylan had seemed stranded in an endless mid-life identity crisis. After his born-again religious conversion and the subsequent trilogy of Christian rock albums in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so many of his fans had lost faith and deserted him.

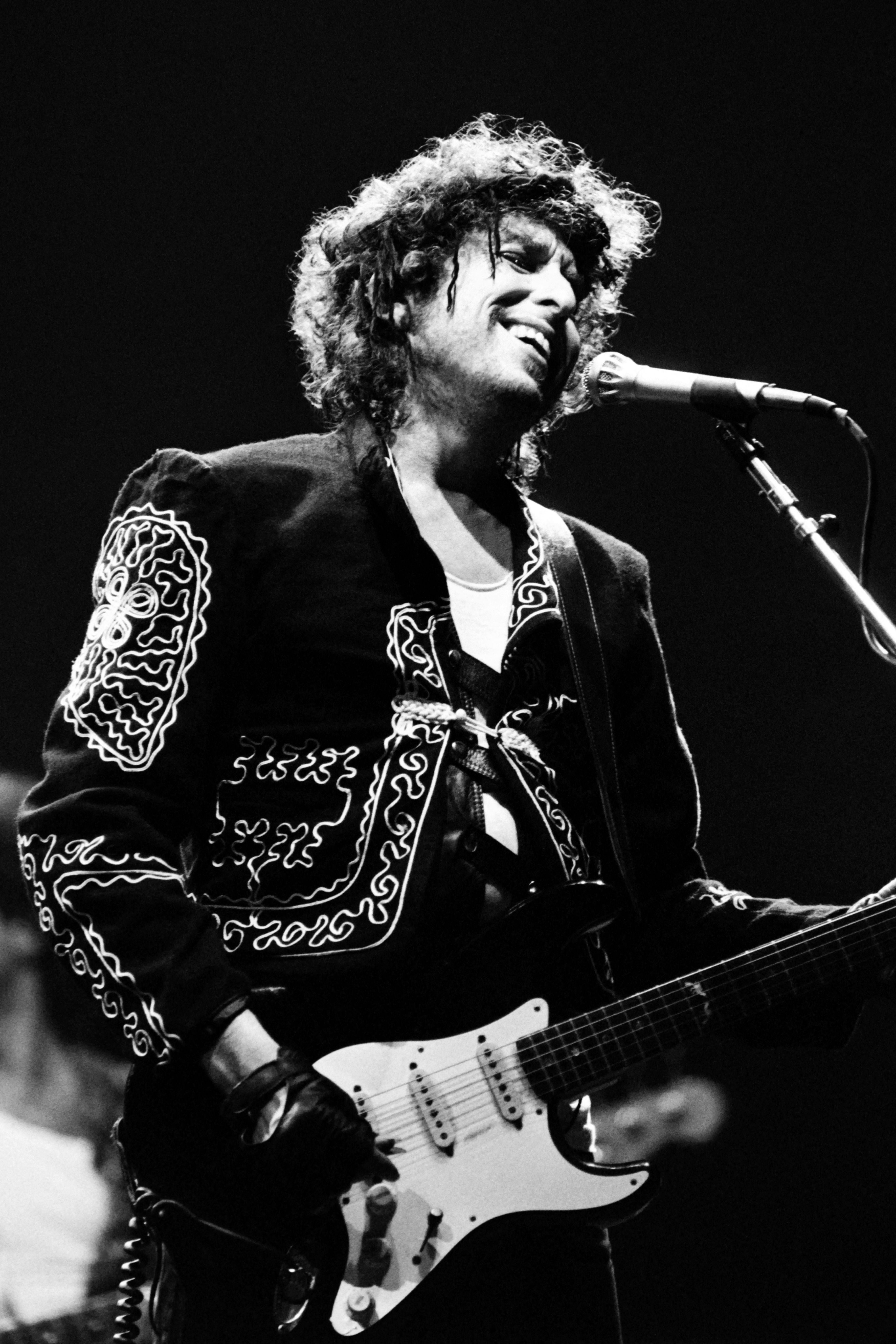

But worse was to come: a misguided quest to remain relevant to the MTV generation led to a string of regrettable albums in the mid-1980s: Empire Burlesque, Knocked Out Loaded and Down in the Groove represent perhaps the true nadir of Dylan’s career.

Although it was slightly uneven, 1989’s Oh Mercy was well received and seen as a partial return to form. But hopes of a revival stalled when Dylan released Under the Red Sky in 1990; it featured lyrics inspired by nursery rhymes and was almost universally derided by critics.

Dylan hadn’t released an album of original compositions since. But the early 1990s shouldn’t be mischaracterised as wilderness years just because Dylan had stopped writing new material.

In fact, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that it was an incredibly regenerative period when Dylan fell back in love with the blues and folk music that had first fired his youthful imagination. Dylan’s live shows were increasingly laced with lovingly reworked versions of the old folks blues standards that have so transfixed the young Robert Zimmerman.

In the early 1950s, even before he was hooked by Elvis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard, he had already fallen in love with folk and blues music. “Late at night I used to listen to Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf blasting in from Shreveport,” he said. “I used to stay up till two, three o’clock in the morning. Listened to all those songs then tried to figure them out. I started playing myself.”

On some night when lightning strikes this gift was given back to me

Although, in reality, Robert Zimmerman was a middle-class boy from Hibbing Minnesota, in his mind’s eye he was already wandering America’s dirt roads and highways, in the company of his heroes, Leadbelly, Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and the Mississippi Sheiks.

In the early 1990s, Dylan recorded two albums that were a direct homage to this most formative period of his youth. Perhaps because they are cover albums, Good As I’ve Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993) have always been criminally underrated for this writer. But by paying tribute to the folk and blues traditions that had so inspired him, Dylan’s creativity was reawakened.

Dylan had feared that his once prolific songwriting abilities had been in an irreversible decline since the 1960s but he would later confide in a journalist that his past influences had restored his imagination. “On some night when lightning strikes this gift was given back to me and I knew it. The essence was back.”

While he was staying with Ronnie Wood in Ireland in 1996, Dylan seemed possessed by that old creative energy, tearing up cigarette packets to quickly scribble ideas and lyrics before he could forget them. Dylan would continue to write songs on his farm in Minnesota during a lonely snowy winter of 1996 but he seemed in no rush to record them.

The recording studio had never been Dylan’s natural habitat. Dylan seemed to equate too much time in the studio with music that lacked spontaneity and authenticity. He had often been accused of passing off glorified live recordings as studio albums in a way that didn’t always do justice to the strength of the material.

Dylan realised that he needed a producer who would challenge his instinctive inclination towards pared-back minimalism. It was only natural that he gravitated back towards Daniel Lanois, the producer responsible for Oh Mercy in 1989. Despite their mutual respect, those sessions had been particularly ill-tempered affairs with one argument said to have nearly escalated into a physical confrontation in the studio’s car park. But Dylan believed that only by subjecting his new songs to Lanois’s “labyrinth of fire” could he hope to fuse his blues folk-roots inspired material with a contemporary new sound.

By 1997 Lanois was something of a star in his own right and part of the new breed of super-producers best known for his work with U2. In a New York hotel room, Dylan read Lanois the lyrics and asked him if he thought he had enough material to make a record. Lanois was stunned by the quality and quantity of the new material, sensing immediately that Dylan was attempting an epic homage to his blues-folk roots.

Time Out of Mind is the sort of blues folk-infused album that Dylan would have loved to have been able to make at the start of his career but those plans had been spectacularly derailed.

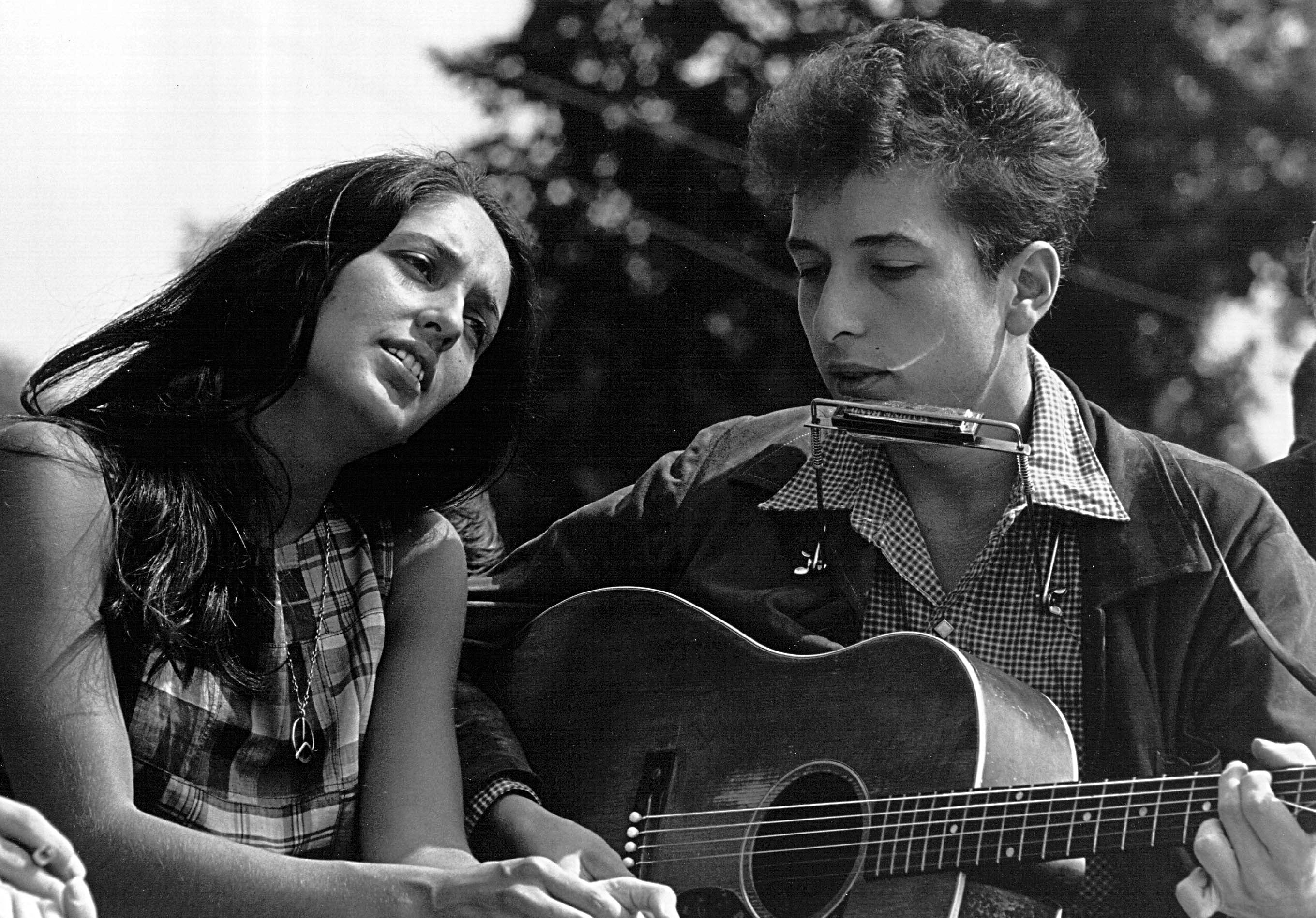

When he’d first emerged as a star on the New York folk scene in 1961, Dylan delighted in telling journalists about his misspent youth as a wandering minstrel, jumping box cars, freight trains and working travelling fairs. In keeping with the tradition of the archetypal blues musician, Dylan claimed to have learned his craft on the open road.

But when a Newsweek article exposed this tall tale as a complete fiction, emphasising instead that Dylan was in fact a nice middle-class Jewish boy from Hibbing, Minnesota, Dylan was stung by the implication that he was a phoney.

In all likelihood, Dylan was only so indignant because he had grown up so steeped in that imaginary world and its music that it had felt true – truer than his actual life at any rate. Dylan sent Lanois home to prepare for the session by listening to Charley Patton, Little Walter and Little Willie John. “I listened to these records, and I understood,” Lanois later said.

After 35 years being battered and bruised by the music industry, heavy drinking and marital breakdowns, Dylan felt he had paid his dues and finally earned the right to call himself a blues singer. And now that Dylan’s vocal cords had spent decades marinating in whiskey and smoke – the hoarse rasp of his delivery had never been better suited to his material of an ageing, itinerant traveller.

Time Out of Mind is a concept album. In each song, Dylan’s narrator plays a blues singer version of himself – on an odyssey through the Amerian South’s labyrinth of dirt roads and highways. He is lovelorn, lost, forever rambling through a picaresque film noir landscape of shadows, clouds of blood, shredding wind and pounding rain. As bleak as that may sound, in the world of Dylan’s imagination living like a rolling stone had always been preferable to standing still. For Dylan, the plight of the wandering blues singer is emblematic of all creative endeavour.

Although they flirt with poverty and are often lonely and exposed, just like an artist, the drifter has agency and autonomy. The open road is synonymous with the freedom to embark on a journey where each step is a chance to create yourself anew. Literally and figuratively, travelling light is the stuff of a creative life well lived. In contrast, eking out a safe, passive, conventional, conformist existence in claustrophobic towns is a kind of spiritual death.

That opposition is foreshadowed in the opening lines of the magnificent opening track, “Lovesick” and dominates the entire album. “I’m walking/through streets that are dead/ Sometimes I want to take to the road and plunder.”

The opener is followed by “Dirt Road Blues”. With its jaunty upright bass, it’s a direct homage to the Elvis Presley Sun Studio sessions and their liberating effect on the young Robert Zimmerman.

Until that moment of awakening, he had been trapped in a state of inertia: “Laying round in a one-room country shack.’’ And from then on he was dutybound to follow his own creative quest. “Gonna walk that country dirt road until my eyes begin to bleed/ Till the chains have been shattered and I been freed’’.

It’s a world where the journey matters far more than the destination. A sense of relentless, roving restlessness prowls through every track. Although the magnificent track “Mississippi” was pulled from the final album, its lyrics lay bare the compromises that trap people in soul-destroying cities, denying them the roving freedom of a reflective life well lived.

“We’re all boxed in, nowhere to escape/ City’s just a jungle, more games to play. Trapped in the heart of it, trying to get away.’’

That same sense of spiritual death arising from physical confinement runs through the album’s superb centrepiece “Not Dark Yet”.

“Time is running away/ Feel like my soul has turned into steel/ There’s not even room enough to be anywhere/ It’s not dark yet but it’s getting there.’’ That yearning for vast open spaces culminates in the extraordinary 17-minute epic “Highlands”.

Superficially inspired by “My heart’s in the Highlands” by Robbie Burns, the song is more of a Keatsian ode to the power of the creative imagination. The narrator flits between urban frustration of “same old rat race, life in the same old cage” and then is effortlessly transported by imagination to the Scottish Highlands where he is immediately free of the clutter of modern life. But really after 17 minutes of surreal shaggy dog story, Dylan’s last words are the true key to the song, Time Out of Mind and, in a sense, his whole career: “Well, I’m already there in my mind and that’s good enough for now.”

Like Keats, Dylan views the highlands of the imagination as far more real and permanent than reality itself. The real world confers roles and responsibilities that deny you the opportunity of creating your true self. To Dylan, the imagination is a portal that can take you anywhere, and to any time away from the fever and the fret of a troubled mind: to a Time Out of Mind, in fact.

In Dylan’s mind’s eye, the blues had always been that bolthole from reality, opening that portal to the vast expanses of his imagination. It was a lesson he learned as a child when he was huddled up under blankets in Hibbing, listening to those illicit radio shows coming out of Shreveport.

In his autobiography, he invests those broadcasts with the miraculous powers of a faith healer. “Back then when something was wrong the radio could lay hands on you you’d be alright.” When his career was faltering in the 1990s, it’s only natural that he would return to the music of his youth for its restorative powers.

For Dylan, there’s no doubt that Time Out of Mind was a turning point – a moment of rebirth

It was almost as if – after so many midlife wrong turns – by going back to his childhood, Dylan had rediscovered a future where he could grow old gracefully. The two albums that would follow it, Love and Theft and Modern Times, are also major works that share the same retrospective blueprint.

The release of Time Out of Mind 25 years ago also coincided with the first serious talk of Dylan one day winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. His ability to reinvent himself in late middle age was regarded as yet further evidence, if it were needed, of his bona fides as a serious artist. Dylan has spent his subsequent career merging his life performances and studio recordings with the great American songbook and by constantly returning to the musical influences of his childhood. When he eventually won the Nobel prize in Literature, it was entirely appropriate that the citation recognised Dylan “for creating new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

Dylan has never forgotten his debt to those late-night radio shows and the way they lit up the open road less travelled to a shy, insecure kid in search of an identity.

“The reason I can stay so single-minded about my music is because it affected me at an early age in a very, very powerful way and it’s all that affected me. And I’m very glad this particular music reached me when it did because frankly if it hadn’t I don’t know what would have become of me,” he has said.

Time Out of Mind is that debt handsomely repaid; it’s a masterpiece.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments