Being black in the US still comes with a particular burden

Former Washington correspondent Mary Dejevsky has visited America on many occasions over the years. Sadly, she is not convinced that the country is about to turn the tide on racism

This time, say many, many well-meaning Americans, it will be different. It feels different, they say. It looks different, they say. We have seen it with our own eyes – by which they mostly mean through the lenses of other people’s phone cameras. They say different people are taking part, not only black people are marching, but white people are turning out in solidarity. And protests are happening in different places: they are not confined to predominantly black areas of cities; protesters have thronged to prominent public spaces, such as Lafayette Square in front of the White House in Washington DC.

All this is true, and it is the hopeful, never-again, response of many white Americans to the agonising, slow-motion killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May. The white policeman’s knee pressing on a black man’s neck, the tortured cry of “I can’t breathe”, have reanimated the Black Lives Matter movement, and not just in the United States. A pledge of support for racial justice has become a set-piece of practically every public occasion, every official’s statement, since.

The death of Jacob Blake last month in Kenosha in Wisconsin, who was killed with a hail of police bullets in his back, has given the protests new impetus all over the US. And feeding into what seems to be a growing climate of anger is the disproportionate number of deaths of black people as a result of coronavirus. From Washington DC in the east to the Pacific city of Portland, via some hitherto quiescent cities in the Midwest, we are seeing a pre-election US with its troubled urban areas yet again in flames. But this time, there is a hopeful consensus. The watershed has been reached. From now on, race relations in the US will be different.

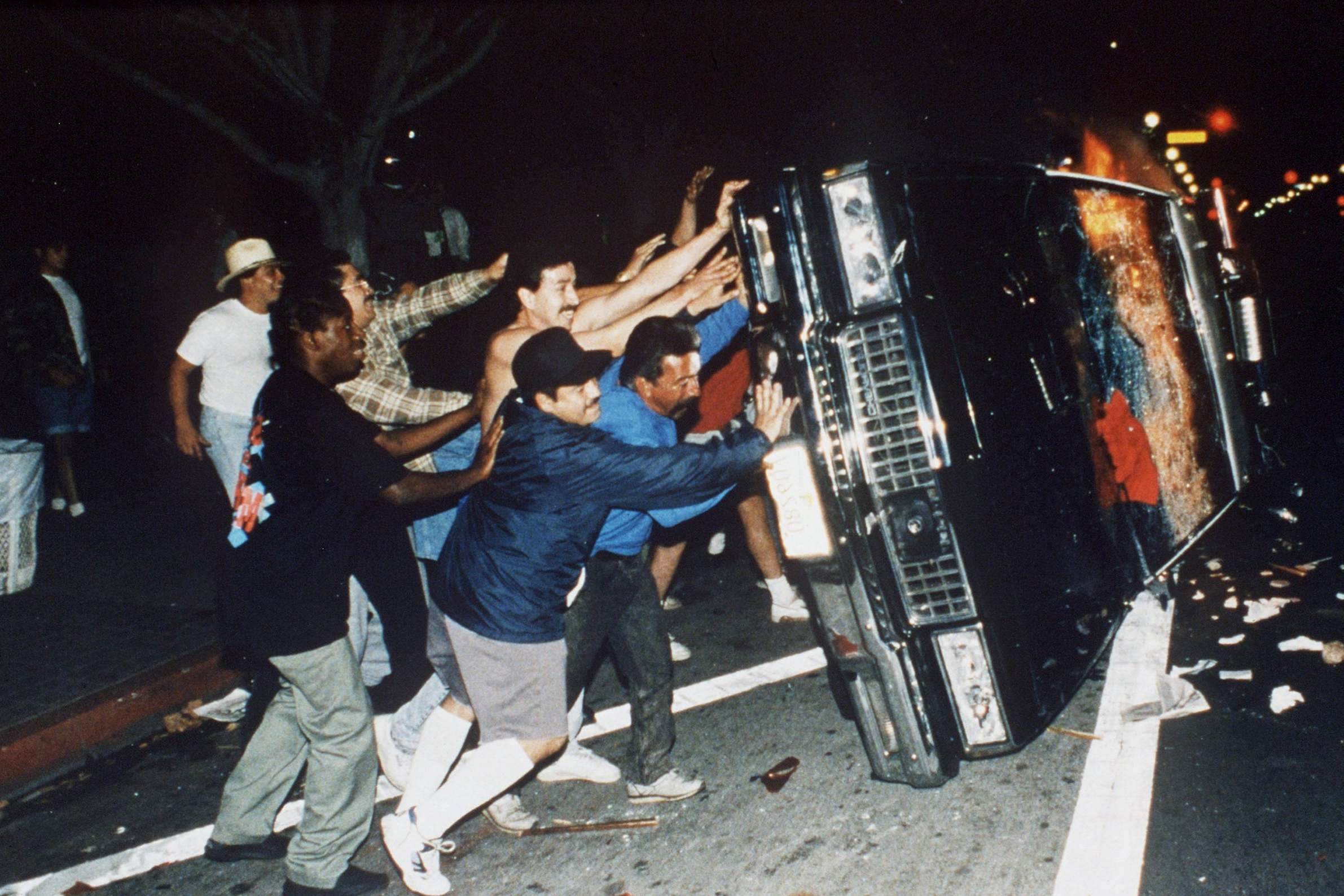

Perhaps they will. But it is a commendable trait of Americans that they tend to err on the side of optimism. As a more sceptical observer from the old world, I am not nearly as confident that change is afoot. This is partly because one of my many visits to the US coincided with the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Described as the largest urban uprising in US history, the violence was sparked by the acquittal of five policemen implicated in an incident not unlike the one that claimed the life of Floyd. They had beaten a black driver by the name of Rodney King, and the shocking brutality had been captured on film.

It is partly also because, when I arrived in Washington in 1997 as the correspondent for The Independent, the city centre still bore some scars of the rioting that had erupted there, as in many US cities, following the assassination of Martin Luther King. That had been in the April of 1968, an annus horribilis for the United States, whose traces remained nearly 30 years on.

Now, it is only fair to say that the improved fortunes of Washington’s downtown since the mid-1990s could be cited in support of American optimism. The downtown has been completely regenerated. It is – or was pre-pandemic – an increasingly lively, well-served, and safe place to be. The so-called front line between districts judged “safe” and “unsafe” has moved a few blocks to the east from where it was 20 years ago.

But there is still a front line – that is, the invisible border between the streets where a cab driver deems it safe to let a white passenger walk alone from the kerb to the front door of the destination, and the addresses where – I was horrified when it happened the first time – the driver feels obliged to accompany you to the threshold and wait until you are let in.

And it is less the big picture than these small experiences, spread over an adult lifetime of visiting the US and almost five years of living there, that fuel my scepticism about whether the country is on the verge of change.

The image is still vivid in my mind’s eye of my first encounter with American “cops”. It was at Port Authority in Manhattan, where I was waiting, with my husband, for a night bus. It was the late 1970s and I had been in the US for all of half a day. The boarding area was patrolled by four policemen.

They were armed; obviously. It was not the guns that drew my attention, though, but the way they walked, their swagger, and the way they fingered their weapons. They had an attitude, and it is an attitude I have noted many times since, and regard, still, as one of those touchstones of the US-Europe cultural divide. Every now and again, especially recently, I seem to detect just a hint of that attitude in what we used to call London “Bobbies”, and hope against hope that I am wrong.

US “cops” may be a tribe apart. But it is race that remains – for me, at least – the least attractive aspect of the US, and specifically the perpetually fraught relations between black and white. For all that the UK’s Black Lives Matter campaigners insist that black Britons suffer many of the same injustices as their American counterparts, and for all that the US has elected a black president for two terms, being black in the US still comes – so it seems to me – with a particular burden. The pent-up tensions can also be mystifying to an outsider.

Twenty years after I had watched those New York cops patrolling the bus station, I was looking for somewhere to live in Washington, and I wanted to avoid the stereotype of the European who automatically gravitates to Georgetown – the favoured area of grand houses and cottages to the immediate west of the centre. Nor did I want the conformity or the car-dependency that attends life in the manicured suburbs. To find anything else, however, proved more easily said than done.

One way of searching for accommodation – pre-internet – was by leafing through little illustrated booklets published by groups of estate agents (realtors). The listings were arranged according to district and included a photo and a brief description. There were photos, too, of the agent responsible, with contact details. What I did not realise initially was that those pictures told the punter as much as the letters and numbers of the city’s postcodes – and, though now transferred largely to the internet, the pictures of the realtors still do.

You can actually visit Washington without seeing any of the black areas. Indeed, many tourist maps don’t include the eastern parts of the city at all

One of the places I shortlisted was a modernist house in the north of the city. Our ambition was to have a house or an apartment that was “American”. I called the realtor. For someone in line for a commission, he sounded distinctly reluctant, and asked several times whether I really wanted a viewing. When I insisted, he agreed to pick me up near my hotel. When he arrived, I read nothing into the fact he was black, but the whole way, he more than hinted that I really wasn’t going to like this house, that I was wasting my time (and his).

It was in a part of the city that juts into Maryland to the north. We approached a decent-looking cul-de-sac, where he parked, pointed out the house and asked whether I wanted to get out. Then I realised, seeing two teenagers shooting hoops on the central grass, that for most of the drive, I had seen only black faces. We walked around the house, which was fine, but too far from transport for my purposes. More to the point, though – it was now clear, though not something that either I or the agent would say – the house was in a black area, and whites don’t live in black areas, just as most black people in Washington don’t live in most of the northwest postcodes. (And, my goodness, isn’t everyone aware of the signal sent by a number or a letter? Except, at that point, me.)

Washington DC is a more southern city than often realised, and – like many American cities – de facto segregated. The days of legal segregation may have gone; there may be a black middle class – and in and around Washington there certainly is. But, from school, through employment to residence, there is very little social mixing. You may think the same about much of the UK, including cosmopolitan London. But in the US, separation is of an entirely different order.

You can visit Washington without seeing any of the black areas. Indeed, many tourist maps don’t include the eastern parts of the city at all. Similarly, you can drive out of the city centre through entirely white districts into Maryland, where you will enter the conspicuously prosperous and almost entirely white Bethesda. We would sometimes go to Bethesda to shop or to eat at weekends, and I found its prosperous whiteness seemed almost embarrassing in the sense that it was so conspicuous and that those who lived there had surely chosen it for that reason. In many ways, Bethesda was becoming a sort of all-white alternative to Washington – better schools, better shops, better civic services – in the same way as other big US cities, such as Atlanta, with Buckhead, have spawned suburban refuges for white flight that have grown into almost alternative cities.

The rapid transition from one area to another, from safety to danger – half a block might make a difference – could make navigating cities a particular challenge, and that certainly applied when I lived in Washington. But it was not until my last year there that I learned why the signposting was so inadequate and why quite major roads seemed suddenly to end. The explanation was twofold. The 1968 riots had brought some road development to a halt, and lack of money meant that plans had never been revived. But the other reason was that new road systems were specifically devised to avoid certain areas. Black areas.

Just as most Britons will identify someone’s region or social class after just a few words, so most Americans can tell instantaneously whether the person on the end of the phone is black or white, and often this affects what happens next

The same went for public transport. There was a reason why the Metro was not extended to Georgetown, though a station had once been mooted. There had been fierce local opposition to a facility that would make it easier not only for residents to come and go, but for others, from other parts of the city, to reach their haven. When I was in Washington there was a spate of knifepoint robberies at Georgetown cashpoints; Clinton’s then health secretary, Donna Shalala, made headlines by fending off one such attack. There, you see, people said, how much worse it could have been if we had had the Metro.

I came across an extreme refinement of this city planning rationale in Philadelphia. There were no half-reasonably priced hotel rooms downtown for reporters covering the 2000 Republican Convention, so I stayed in a pleasant nearby town, essentially a suburb, called Chestnut Hill. Proceedings ended late, the suburban trains had stopped running, so a cab back was the only option. The first two nights, the cab sped along a smooth dual carriageway through what seemed, in the dark, a rural landscape.

On the third evening, the cab (with a black driver) took a quite different route, which was far more direct, and quicker at that time of night. It turned out that this was the battered old road and the tram route that wended its way through the northwest of the city. The new road meant that commuters from the plush suburbs to Philadelphia’s venerable downtown not only avoided having to rub shoulders with their poorer, mainly black, fellow citizens, but that they never had to cross paths with them either. It raised the term “parallel lives” to a whole new level.

Those parallel lives were, and are, to be found in cities all over the United States. Sorting through old papers recently, I unearthed a study, published by the Brookings Institution – a liberal Washington thinktank – of the demographics and city planning of Minneapolis. It concluded that, even by US standards, this city was unusually polarised – polarised, that is, along black-white lines, with the income gap among the widest in the country. This was a surprise, as such divisions were generally associated with grittier conurbations, such as Los Angeles and Chicago, not with an ostensibly successful city in the predominantly white, farming state of Minnesota. I mention this only because, decades later, Minneapolis was the city where George Floyd lost his life.

This black-white separation may help to explain something else that it is hard to ignore about race in the United States. Early on in my time in Washington, I wanted to pay a bill at the bank, but I simply could not understand the teller’s response from behind the glass. She kept saying, then shouting, “Kaysh, kaysh”. I was flummoxed, and so was she. The deadlock was broken only when an elderly man, waiting at the next counter, said she was asking whether I wanted “cash”. It was a misunderstanding that you might have laughed off in the UK. Here, it was no laughing matter; she glared. I simply could not understand her (black) accent, though she could just about decipher my British English.

Such communications difficulties are not unique to newly arrived Brits, however. Just as most Britons will identify someone’s region or social class after just a few words, so most Americans can tell instantaneously whether the person on the end of the phone is black or white, and often this affects what happens next. I cringe at the memory of how some, even highly educated, otherwise polite and correct, white Americans would talk – in my presence – to black people, whether on the phone or in offices and shops. There was something about the tone and the lack of eye contact that implied superiority – yet the white speakers seemed completely unaware of how they were being heard.

Could it happen? Could George Floyd’s death mark the watershed? Well, maybe social media and mobile phones with cameras will alter police – and other officials’ – behaviour. That, by itself, would be a positive development

The response, which was hardly surprising, could be a bolshie obstinacy on the part of black officials – which reminded me of the old Soviet Union – and rarely ended well. Similar tensions could – and still can – be experienced where black and white pedestrians share the same pavement space. I was astonished, arriving in Washington, to find city pavements essentially a competitive zone, with zero sense of give and take. Younger black pedestrians, especially, stubbornly stuck to their course; giving way amounted to being “dissed”.

The generally poor state of race relations was something that Bill Clinton, then entering his second term and dubbed by some “American’s first black president”, had said he wanted to address. One initiative, which made its way into the State Department and involved some of the foreign journalists, was for white officials to invite their black colleagues to dinner in their homes as a prelude to an after-dinner discussion on how to improve things.

I was a guest at two such occasions, one of which descended into such furious argument that the two foreign journalists found themselves trying to call a truce and offer some sort of mediation. It all started well enough, with warm words on either side. But the words were not the problem. The tension sprang from the patronising tone and the awkward body language on the white side. Of course, socialising across ethnic lines in the UK – probably still more in France – can have its pitfalls, especially when it has been artificially encouraged. But the passive aggression to be felt here reflected a gulf that seemed almost unbridgeable. At least this is how it seemed at the time, and still seems to me to this day.

The one saving grace, here and on other occasions, was that I was more of a bystander than a participant. Inevitably, though, there came a time when I found myself dragged into the all-American agony around race. I had arrived back from a work trip to Baltimore airport – it was my least favourite Washington airport because it was further from my part of town. This time, it was the middle of the evening, already dark and raining. There was a long queue for taxis.

When I reached the front, I noticed an elderly couple, and asked if they were going into Washington and whether they would like to share my cab. I thought I was doing a good deed. Once in the cab, we exchanged the normal pleasantries about where we were from. Scarcely had we reached the main dual carriageway, however, that their tone changed. They wanted the driver to take a huge detour to the north to take them straight to their northwest Washington suburb. I had expected to take the direct road through eastern DC into downtown, where I would get out, and it would be maybe another five minutes to the north for them.

Dear oh dear. The gloves were off. They were adamant that they wanted to take the detour. The direct route was dangerous (ie it went through mainly black districts). I appealed to the driver. He said the cab was mine and it was my decision. I asked him to use the direct route – he was black, he was quite happy with that. The elderly Washingtonians were not. He demonstratively got out his umbrella, as a defensive weapon. He said his wife was terrified. We would be held up at gunpoint. The driver was on no account to stop, even at a red light. (Johannesburg was the last time and place I had heard such an instruction.) His wife then weighed in to dismiss me as an ignorant European with no idea of American reality who was endangering other (good) people’s lives. We passed the rest of the (uneventful) journey in stony silence.

Paradoxically, the part of the United States where I found relations between black and white most relaxed, with a degree of respect generally going both ways, was where you might expect it least: in the Deep South. One explanation – surprising, but not implausible – is that black and white have lived there in close proximity for longer and know each other and each other’s ways better than they do elsewhere in the country.

Whether this is true or not, I remain amazed that there has never been an all-out revolt by black Americans against the white patronage they labour under day by day. The protracted riots of 1968 are probably the closest the country has come to a race war, and this is not what we are seeing today.

I would stress that I have given just a few vignettes from my own experience. I have not ventured into the bigger picture: of education and income disparities, poor healthcare, the disproportionate prison population, and the obstacles to black voter registration and actual voting. Some of my observations may be out of date, but when I spent some time in the US this time last year, change on the race relations front at least was hard to find.

Could it happen? Could George Floyd’s death mark the watershed? Well, maybe social media and mobile phones with cameras will alter police – and other officials’ – behaviour. That, by itself, would be a positive development, and it could happen. But will attitudes change? Inadequately qualified as I am – a white, foreign observer without roots in the US – you will forgive me, perhaps, for striking a note of pessimism. It is not clear to me that the hopes of today can be realised, not just now, but within even a generation. The inequities and the tensions are entrenched in a whole cast of mind, and a whole history, and I am not sure they can be so summarily expunged.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments