Bessie Coleman: the black, female pilot who fought the status quo

Although her career was brief – Coleman met her untimely death at only 34 – the aviator took over the skies and paved the way for an entire generation of pilots, writes Olivia Campbell

The skies were clear over New York’s Curtiss Airfield on 3 September 1922. Hundreds of spectators had gathered at an air show put on in honour of the first African American regiment sent to France during the First World War. A plane above them glided through the air, dazzling the crowd below with spirals and loops that seemed to defy the laws of physics.

The daring pilot was Bessie Coleman, a fearless aviator who, for a few short years, achieved fame in the 1920s for her talent to pull off dangerous manoeuvres in her surplus military plane. Coleman reached new heights, literally and metaphorically, by becoming the first African American woman to achieve her pilot license 100 years this week.

Although her career was brief – Coleman met her untimely death at only 34 – the aviator took over the skies and paved the way for an entire generation of pilots. Before there was Amelia Earhart or Jacqueline Cochran there was “Queen Bess”.

“Bessie Coleman in life was a challenge to the status quo,” Doris L Rich writes in her book, Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator. “[Her life] was a constant struggle against the myriad of limitations conventional society erected against anyone who dared to be different.”

The Twenties was a decade defined by innovations in air travel and perhaps the most quintessential symbol of this exciting time was that of the barnstormer, daredevil pilots who took to the skies to perform elaborate stunts. If you couldn’t catch these thrill-seekers at a show near you, fuzzy newsreels of their escapades were broadcast around the country. They were the celebrities of their day and Coleman was determined to join their ranks.

Coleman was always in pursuit of knowledge and had made it to university, a hard feat for women in the 1920s, let alone a black one

But the path to the skies was a difficult one. Jim Crow laws in her home state of Texas and the entrenched racism and sexism that was pervasive in US society meant that Coleman would face barriers that no white man would have to endure. Whatever she wanted to do would be met with a struggle. For her 10th child, Coleman’s mother didn’t want her daughter to be stuck picking cotton and living in poverty like she had. This view would push her towards reaching the heavens.

At 23, she was at a crossroads in her life. Coleman was always in pursuit of knowledge and had made it to university, a hard feat for women in the 1920s, let alone a black woman. However, she was forced to drop out after only one term due to lack of funding. After moving to Chicago, a place with more opportunity than a small town in Texas, it became more crucial than ever for Coleman to find her place.

It was while working as a manicurist that she became enthralled with stories she heard of pilots who fought in the First World War. Her brothers, who had served in the military, told her stories of battles in far-away lands. Some of her customers were also veterans of the conflict and they indulged her with tales of danger and heroism in enemy skies.

A pilot had to be fearless; to be tenacious and bold; Coleman was no doubt those things and soon an image that had formed in her mind seemed like the only thing she could pursue.

However, she soon encountered her first hurdle. Aviation was very much a pursuit for white men in the US and many were keen to keep it that way. Coleman wrote to countless flight schools in America but was rejected by all of them. For the simple matter of being both African American and a woman, Coleman found she was left on the outside of this club. White men wouldn’t teach her, and no black aviators could.

It was clear the US was not ready for her. Robert Abbot, publisher of the influential black newspaper The Chicago Defender, suggested Coleman seek training overseas in France, where attitudes towards race and gender were much more liberal. Soon she enrolled in French lessons (applications had to be in perfect French) and took an extra job as a manager at a chili parlour. Her hard work soon paid off and she was accepted into the Caudron School of Aviation, a renowned institution run by brothers Gaston and Rene Caudron near the Somme.

On 20 November 1920, Coleman stepped aboard the SS Impersonator and was on her way to her dream.

In the 1920s, France had established itself as a nation at the forefront of cutting-edge air travel. From as early as 1783, when Francois Rozier flew over Paris in the first human flight in a hot air balloon, daredevil journeys and air-related feats were part of France’s heritage. Women were not excluded from this prestige: Parisian Raymonde de Laroche, who became the first licensed female pilot on 8 March 1910, and Marie Marvingt, the first woman to fly on combat missions, were just some of the trailblazers to come from across the pond.

Coleman began a seven-month course to learn how to fly a Nieuport Type 82, a 27-ft-long biplane that was known to stall mid-air. The school, which she had to walk nine miles to every day, put them through training which was not only gruelling, but physically dangerous. She was even made to sign a waiver saying she took all responsibility in the event of her own death.

Her plane was flimsy, and Coleman had to inspect every part of it each time she took to the skies. Instead of a steering wheel and brakes, there was a large wooden stick that could control movements and a bar was used to turn the aircraft. Unlike modern commercial jets, they wouldn’t glide to a graceful halt. Instead, it was a metal skid that dragged along the ground that would bring it to a stop.

The aviator-to-be remained undaunted, even when she witnessed a fellow classmate plummet to their death. “It was a terrible shock to my nerves, but I never lost them,” Coleman would later tell a newspaper. At the Caudron School she learned the aerial manoeuvres that would bring her fame, like the loop-the-loops and tailspins.

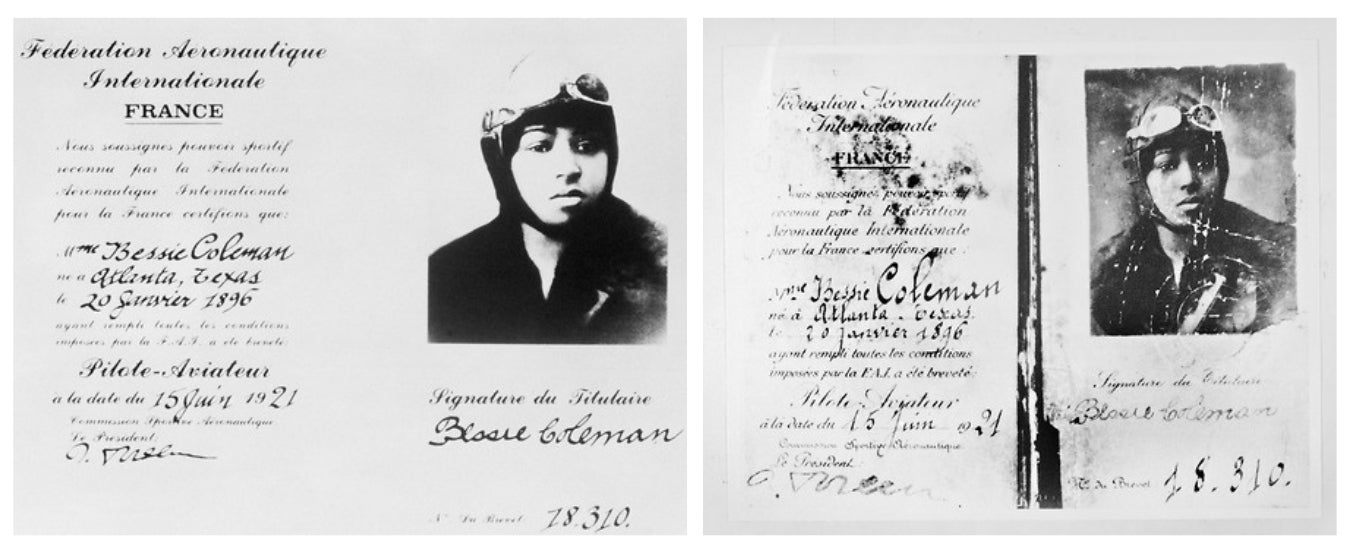

On 15 June 1921, Coleman was awarded her license by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, a document honoured and recognised by every nation in the world. She had now become the first African American woman to achieve this feat. But not one to stop there, Coleman had another goal – to open the first flight school for African Americans.

True to her goal of encouraging black people to take up aviation, she worked tirelessly to spread the word

It was time to return to the US, and although she was largely ignored by white media, several news outlets praised her success and recognised the significance of what she had achieved. A September edition from the Associated Press said: “Today [Coleman] has returned a full-fledged aviatrix, said to be the first of her race.”

As well as conquering the skies for herself, part of Coleman’s mission was to inspire other African American people to pursue aviation. Advancements in flight technology had been thrust forward by the First World War and it soon became clear that the industry would be integral to the US’s future economic development. It was Coleman’s view that if black people wanted to change society, establishing themselves within aviation was paramount.

“The air is the only place free from prejudices,” Coleman said. “I knew [African Americans] had no aviators … so I thought it my duty to learn aviation and to encourage flying among men and women of our race who are so behind the white race in this modern society.”

Coleman’s next step was to earn a living to fund her future flight school – and barnstorming was the way to do this. More training was needed if she was to perform more audacious stunts and so once again she found herself applying to flight schools. However, while she had demonstrated she was more than capable of holding her own in a plane, an African American woman was just too much for conservative America to handle.

Still unable to enrol in a US flight school, Coleman once again returned to France for advanced training in 1922. Her second stint took her across Europe to the Netherlands and Switzerland; she studied with renowned First World War pilots in Germany; and tested aircraft in the Netherlands for “Flying Dutchman” Anthony Fokker. Her skills and flair for showmanship earned her widespread appeal across the continent. Headlines praising her talent were splashed across newspapers, with some even declaring Coleman to be one of the best flyers they had ever seen.

She stepped foot back on US soil with the skills she needed to perform. Meanwhile, a growing interest in this small woman (she was only 5”3) and her death-defying manoeuvres spread. Her first air show in September 1922 in New York was met with acclaim and a second show in Memphis, Tennessee, saw similar reactions. Soon word was travelling about “the only race aviatrix in the world”.

With Wills co-piloting, the duo was taking a test flight when the plane went into a sudden nosedive at around 3,000ft

When not putting on exhibitions, Coleman was flying up and down the country giving lectures or taking patrons on shorts ride for a fee of $5 (around £50 now). True to her goal of encouraging black people to take up aviation, she worked tirelessly to spread the word. A show in Chicago, which drew in a crowd of over 2,000, saw Coleman perform, with her sister as passenger, a series of bold moves in October 1922. After seemingly losing control, she was able to perfectly execute the figure-eight manoeuvre for a crowd of ecstatic onlookers. Such feats had earned her the nickname “Brave Bessie”. It was time to bring her show south and she was soon flying over carnivals and fairs.

However, among all the bravado and showmanship was the shadow of danger. If you wanted to be the best barnstormer, your tricks had to become more complex and with complexity came greater risk. Furthermore, planes were often old and poorly maintained; according to some sources, aircraft were sometimes so worn they were held together with wire and glue. It is no surprise that some barnstormers faced serious injury, and possibly even death, every time they turned on the engine.

It was only so long before Coleman had her first brush with death. After finally securing a plane of her own, a show in California in February 1923 brought her excitement to an abrupt halt. Performing for a crowd of 10,000, the plane motor stalled in mid-air and crashed down towards the ground. Despite suffering a broken leg and several broken ribs, she told journalists: “As soon I can walk, I’m going to fly.” It would be nearly a year later that Coleman would be able to get back in her plane again and begin raising money for her school.

Her next scare would be her last. In April 1926, she had been due to perform a number of air shows in Florida and a newly purchased plane was being flown down from Dallas. The journey down had been plagued with problems: her mechanic William D Wills had been forced to make several extra stops as the engine had been so poorly maintained. Even her own family members pleaded with her not to go ahead when they heard of the problems.

But ever determined, Coleman had a show to put on. With Wills co-piloting, the duo was taking a test flight when the plane went into a sudden nosedive at around 3,000ft and flipped over. Coleman, who had stood up to scout out locations for a planned parachute jump the next day, was thrown from her beloved aircraft and fell 2,000ft. She was dead upon impact. Wills, unable to regain control, came down with the plane a few seconds later.

Just like that, Coleman’s life was gone and with it her dream of opening her own flight school. News of her demise spread fast and people poured in to pay their respects. Thousands of people had been due to attend her air show but instead found they were visiting her memorial service to say goodbye. Her body was moved to Chicago, where she was given a military escort from overseas veterans of the African American Eighth Infantry. Activist Ida B Wells led the funeral and more than 5,000 people came to see her off.

It’s easy to see the impact this feisty woman from Texas had on aviation. Thousands of people, black and white, have been inspired to pursue a career in the field, enamoured with her resilience and determination. Although her flight school never became a reality, her dream to encourage African American people to take to the sky did.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments