The fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of east European tourism

Once upon a time, going to Prague would have been a bureaucratic nightmare, but today the city is flooded with tourists. From the Wild West-era to the Age of Irony, Mark Jones traces the three stages of post-1989 eastern European tourism

I had a supervisor at university who’d travelled a lot in eastern Europe for the British Council. I can’t swear he was an ex-spy, but that was pretty much the perfect CV for an ex-spy in the early 1980s. One day, when we should have been deep in EM Forster, he started talking to a group of us about Prague: eloquently and at length. I can’t remember the exact words and this being a supervision I was probably only half-listening. But the overall message was: Prague is the most beautiful city in the world, and if you get the chance, you must go there.

This came as a surprise, as we’d assumed Soviet-era capitals were uniformly grey and Brutalist. Not that we ever would get the chance to see the place for ourselves: not unless we went into the spying business. Those last years of the Cold War were tense and nasty. In my second year, we were seriously worried about Margaret Thatcher introducing conscription as the threat of a Soviet occupation of Poland grew.

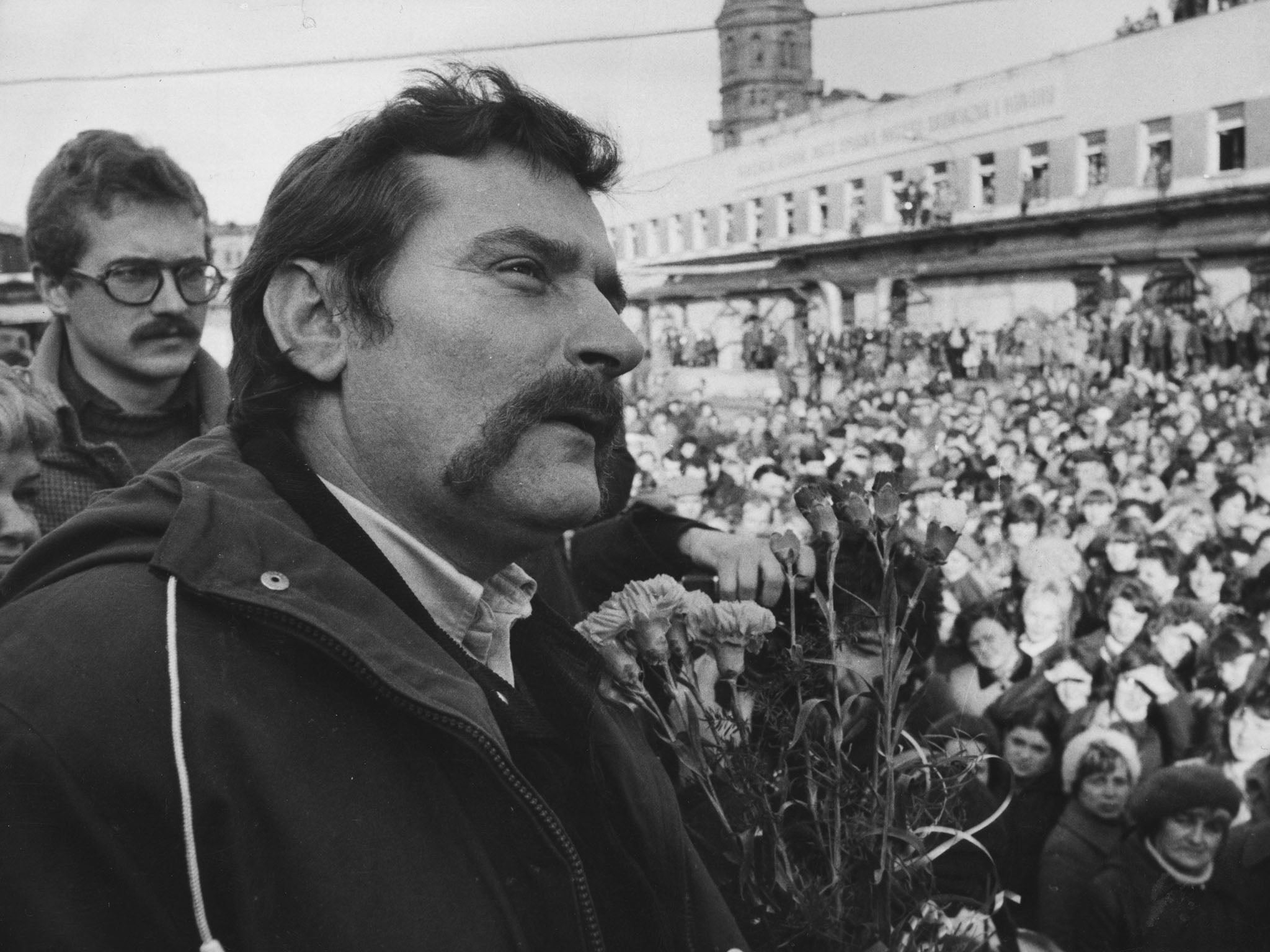

So at that time, we students would no sooner think of going to Prague (or Budapest, or Bucharest, or Tbilisi) than Timbuktu. The bureaucracy involved in getting to Timbuktu might have been more straightforward. But at the end of the decade, I did get behind the Iron Curtain before it was ripped down. My south London football team, the Racing Club de Blackheath (which come to think of it, may have had players with espionage tendencies), decided we’d had enough of predictable annual tours to nice places like Italy and France: we’d head to Poland instead. The Soviet tanks had not arrived: Lech Walesa had.

We started applying for visas a couple of months before the trip. I have dim memories of entering a posh Portland Place building and sitting in waiting rooms that made your local NHS surgeries feel as customer-friendly as the Savoy. There were reams of grey, badly-printed forms to fill in. We might be tolerated, but it was clear we wouldn’t be welcome.

There were no direct flights with Wizz, nor EasyJet. We got a scheduled service to West Berlin, then crossed by rail. This urban enclave of capitalism felt suburban, affluent and boring, a Mercedes saloon of a city – not at all the Berlin we’ve come to know since. The documentary maker in charge of my memory films the crossing in the style of Fritz Lang adapting Kafka. Grey tenements loom beyond the window, border guards in heavy boots snatch our documents, fellow passengers avoid eye contact. But that’s probably docu-drama rather than an objective record: three decades and a lot of John Le Carre can play tricks with recall.

You can have more trust in my recollection of emerging from Friedrichstrasse station. Friedrichstrasse itself was austere and empty as the dawn before a grand parade. After West Berlin’s hoardings and shopfronts, the cityscape felt distinguished, sad and closed.

In Poland, by contrast, the windows and doors were ajar and there were definite hints of spring after the long Soviet winter. Walesa’s trade union Solidarity would be allowed to field candidates in elections. This was the beginning of an end that would come six months later with men holding pickaxes above a graffiti’d wall. But for now, the Party managers who gave us a tour of their factory in the northern town of Koszalin could not have looked more secure of their place in a settled and progressive economy. We were welcomed like an important trade delegation rather than what we were: a bunch of hungover twentysomething London parks footballers.

Like Barcelona, Venice, Dubrovnik and Amsterdam, Prague has become a victim of overtourism, a casualty of its own beauty. What a fine Central European kind of irony that is

The Polish footballers and Solidarity people told a different story. We chatted to them freely after the games as they opened up car boots full of bootleg Zywiec beer. They gave us their own unofficial guide to a country too cynical to hope for much: but too hopeful to give in to cynicism.

The city streets, the cafes and the shops told their own story too. You’ll be familiar with these tales of Soviet-era hardship and shortage by now. But I have to tell myself again what it is like when a country cannot reasonably provide for its people. It’s a valuable thing to have witnessed in a Britain where the hard-left still won’t recognise the failures of those command economies and the hard-right seems to positively welcome the prospect of food shortages and empty shop shelves as long as it’s in the service of our national self-image.

We drove through mile after mile of rich farmland, yet there wasn’t a fresh vegetable in the shops or on the dining tables. What produce the collective farms did manage to rustle up was being shipped to Mother Russia. The past really was another country. The only luxury goods were in the foreign currency Pewex shops. I am not making this up: next to a colour TV, you’d see an orange.

Remember, we were tourists, so we were in the market for any luxuries going. They included sitting in a cafe in a fine Baroque square with a cold beer on a fine sunny day. You couldn’t: not in Poznan’s Old Town, anyway. The one bar was underground and the only alcohol on offer was methylated brandy. In the Grand Hotel in Wodz, the starter salad was a single yellowing lettuce leaf drizzled with Carnation milk. There was only mildly toxic orange squash to drink.

That was not a great way to end any football tour. The next day, my docu-drama has a heavy-set Russian female guard shouting at us and rattling a huge bunch of keys. We were on the wrong train with the wrong documents – everything about us was wrong, in fact. But somehow we made it back to West Berlin, where we headed to the nearest cafe for a litre of freedom beer. It was just before 9am.

Just three years later, with the titanic battle of the systems seemingly over, Francis Fukuyama was announcing that history was dead. Having seen history being made, the Racing Club team returned again and again to the former Soviet states in the post-history years of the 1990s: to Poland again (twice), Hungary, Romania, Russia, Latvia and Estonia; then further afield to Georgia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekhistan.

And in 1991 we went to what was still called Czechoslovakia. That meant I saw Prague, the place I never expected to see. My mental documentary maker has got the soundtrack all sorted out: Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”. Pirated ghetto blasters and CDs were everywhere. (So were porn mags.) And as the director gets creative with my neural pathways, Prague at night becomes a set from Jon Landis’s “Thriller” video: all funk, neon, sleaze and Gothic. Yet by day, the town was as pure and beautiful as my tutor promised.

We were filthy rich. In Poland on that first trip, we gave the taxi driver fistfuls of Zlotys, simply because we were tired of lugging the stuff around. “Yay!!” he cried, punching the steering wheel. In Budapest, we did a roaring trade on the black market – and everyone was a dealer. At the other end of the train line, we tried the same in Prague and were stiffly rebuffed. “Havel wouldn’t like it,” said one, referring to the president, writer and conscience of the Velvet revolution.

And like all filthy rich tourists, we behaved terribly. After one record-breaking post-match session in Budapest, I, with two midfielders, invented the sport of Trabbi-hopping. A year after the ubiquitous and notorious East German Trabant sedan ceased production, the streets were still full of them. The shell was made of a resin plastic called Duroplast. You could stand on the roof of a Trabbi, step off and it would spring back to how it was before without a trace. Trabbi-hopping required the competitor to see how far you could get on a Budapest street without touching the ground.

We were boasting of our exploits the next day. A wife of one of the players was not impressed: “Do you know how long it takes for someone to earn the money to buy one of those cars?”

The film rolls on through the 1990s. We see Versace-clad heavies on the beachfront at Riga and a McDonald’s opening its doors on Krakow’s main square. The first British stag parties start to appear in Tallinn old town. (We were past our Trabbi-hopping phase by this stage, and rather sniffy about lads from Macclesfield and Reading arriving on our turf. But in Tallinn, we were all vastly outnumbered by booze-cruisers from nearby, heavily taxed and thirsty Helsinki.)

There have been three ages of post-1989 eastern European tourism. The first, Wild West-era had petered out by the turn of the century. Next came the Age of Exploitation as the estate agents, top chefs and luxury hotel brands moved in. The Four Seasons hotel opened in Prague in 2001. This was no longer the city of dark pubs, soup and cheap beer, kiosks stocked with porn mags and street vendors with their knock-off ghetto blasters. In Poland, British Airways invited me to the launch of their new Krakow route: a VIP train from Warsaw, an orchestra playing Delibes’ Lakme in the square.

Only those ageing folk suffering from the psychopathological condition known as nostalgia truly yearn for the pre-1989 days

Then came the current era, the Age of Irony. It’s been led by our old friend, the Trabant. From Berlin to Budapest, Transylvania to Sofia, you can hop in a Trabbi while a wry millennial drives around the sights telling you samizdat jokes about a Communist officialdom that was as risible as it was vindictive. Today, there are day-glo Trabbis, Trabbis in animal prints, open-top Trabbis, stretch-limo Trabbis, all parading their TripAdvisor reviews like badges of honour (”Lots of fun and fumes!” “Who thought a deserted steelworks could be so interesting? Brilliant experience!”)

Let’s hope irony and the great central and eastern European tradition of poking merciless fun at their pompous leaders survives the advent of Orban in Hungary and the Law and Justice Party in Poland. Right-wing nationalists don’t like jokes any more than old-style communists.

While we Westerners are gawping at old steelworks and laughing at jokes about secret policemen, the Easterns and Middle-Europeans have been gritting their teeth and getting through the three-decade-long process of readjustment and reinvention. The kleptocrats and gangsters are still around. So are talented entrepreneurs and administrators.

A new poll by the Pew Research Centre shows that 78 per cent of Czechs and 81 per cent of Poles think their standard of living is vastly improved. In less dynamic and cosmopolitan places, the results are more mixed: but only those ageing folk suffering from the psychopathological condition known as nostalgia truly yearn for the pre-1989 days.

Let’s end back in Prague, that wondrous, half-mythical city conjured up by my tutor all those years ago. Today, 30 years after the joyous party that was the Velvet Revolution, Prague citizens, Prazans, are revolting again: not against the Party, but parties. The historic centre, Prague 1, has become a no-go area for locals as nine million visitors a year flood the place, a good proportion of them on an epic pub crawl. Like Barcelona, Venice, Dubrovnik and Amsterdam, Prague has become a victim of overtourism, a casualty of its own beauty. What a fine Central European kind of irony that is.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks