‘People were crying as they built it around us’: The day the wall went up

In the west it was known as ‘the wall of shame’, built for just one purpose: to keep East Germans in. On the 30th anniversary of its fall, Mick O’Hare returns to 1961 and hears stories from both sides of the border

The crowd of Berliners that had gathered to watch were looking confused, some were starting to get angry. Concrete blocks and barbed wire were being placed across the streets as armed soldiers looked grimly on.

It was 15 August 1961, the third day after East Germany had begun building the Berlin Wall. Some of those about to be encircled in what would become West Berlin had begun to shout to people on the eastern side telling them to escape while they could.

Conrad Schumann heard them. The 19-year-old was on the front line, a border guard building a border that was getting higher with every passing hour. So on the spur of the moment, he took a punt, reckoning that by the time his colleagues had seen what was happening and raised their rifles he’d be over the wire and on the other side. Schumann ran…

His photograph was all over the world’s media the next day, leaping over the barbed wire that had been strewn across Bernauer Strasse, and it still adorns postcards at newstands all over Berlin. His was the first successful escape over the Berlin Wall. It would not be long before the first death. Ida Siekmann, a 58-year-old nurse, was fatally injured as she attempted to escape by jumping into West Berlin from a window in a house also, ironically, on Bernauer Strasse.

After the victorious Allies divided up Germany at the end of the Second World War the capital Berlin lay wholly in territory occupied by the Soviet Union. But the city itself was subsequently divided into four sectors: British, American French and Soviet, meaning that the first three were, in turn, wholly surrounded by the Soviet Union’s occupied zone – what would become the German Democratic Republic (DDR) or East Germany.

At first, travel was generally permitted between the various sectors, especially in Berlin where people had to travel for work, shopping or to see family. But people from East Germany began to see how West Germans – backed by the US-funded Marshall Plan introduced to rebuild and democratise Germany and Europe after the defeat of Nazism – lived. Homes, possessions, jobs, more and better food – the quality of life in the west was apparent to all. Migration from east to west began.

Between the declaration of the East German republic in 1949 and 1961 about 2.7 million people, getting on for 20 per cent of the population, many skilled and intellectual, chose to leave, most of them under the age of 25. It was, essentially, a “brain drain” from east to west.

In the summer of 1961, almost 2,000 were leaving each day and the easy route was by simply crossing into West Berlin… essentially all you had to do was walk down the street. By 1961, 90 per cent of all East Germans leaving for the west did so through Berlin.

The Soviet-backed communist government ruling East Germany began to panic – economic and social collapse was beckoning and the Soviet Union was casting its gaze over its weakening satellite state. Only two months before, Walter Ulbricht, the East German head of state, had announced that “no one has any intention of erecting a wall”.

But East Germany was always going to pay fealty to its paymasters in the Kremlin. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev recommended that transit between east and west be closed off.

We didn’t know what was happening. People in the streets were crying as they built the wall surrounding us. The British soldiers at the checkpoint near us didn’t have any answers and my mum was fraught with worry because her sister lived in East Berlin

The Soviets had attempted this before, ostensibly over the introduction of the West German Deutschmark to West Berlin, which they believed would damage their aim of unifying that part of the city with the rest of East Germany. They tried to starve West Berlin of provisions by cutting off all roads, railways and waterways to the city.

This land blockade was usurped by the Berlin Airlift of 1948 and 1949 as around the clock British, French and American planes alongside other western air forces flew the 150 kilometres from West Germany to the exclave that was West Berlin, ensuring its population was fed and clothed.

The blockade had failed so, although reports vary about who proposed the initiative and whether Ulbricht lied or had a change of heart, it would seem that this time Khrushchev insisted on the wall that Ulbricht said he wouldn’t build. Considering the dramatic and grim effects that its construction would come to embody, there is a peculiar incongruity that the order to build it was signed by Ulbricht at a garden party in the rural and picturesque Dollnsee to the north of Berlin.

In the early hours of 13 August reports began coming into West Berlin police stations that East German troops were approaching the border. The streets to West Berlin were closed, streetlights were turned off and the road surfaces ripped up. Associated Press reported that the Brandenburg Gate had been closed off.

Temporary barriers of barbed wire and concrete blocks, put in place by 40,000 police, soldiers and workers, appeared overnight. The DDR insisted that they were necessary to stop the reactionary forces of the imperialist west encroaching on East German territory and to stamp out the effects of the “pernicious capitalist culture” they insisted was infecting their citizens.

They coined the barrier “the antifascist protection rampart” but nobody ever got shot trying to come over from the west. Indeed in the west it was known as “the wall of shame”. The wall had just one purpose: to keep East Germans in.

People who had regularly crossed the border to work and socialise were turned away. “I used to take the train into West Berlin,” says Dorothea Breitner, now aged 78, “But the morning the wall went up, the guards had closed the station. I thought that my boss would be angry with me when I turned up the next day. I didn’t realise that I would never speak to him again.”

News was slow to leak out at the time because it was all controlled by the government … My family in Berlin eventually told me it had gone up. I wasn’t surprised. My small town Furstenwalde had been drained of young people fleeing to the west. It was a meagre existence. I knew the government would stop them one way or another

People on the west were scared too. The day the wall went up communications with the east were severed. “We didn’t know what was happening,” says Ulrika Muller, who was then a teenager. “People in the streets were crying as they built the wall surrounding us. The British soldiers at the checkpoint near us didn’t have any answers and my mum was fraught with worry because her sister lived in East Berlin and she couldn’t contact her. It was weeks before we knew our family in the east was OK.”

“I packed a bag,” says Mariam Flotow, who had only just moved to West Berlin after divorcing her husband. “I thought another war was coming.” The wall had appeared so suddenly that people who had spent the night in a part of the city that wasn’t their home could not return. Until 1989 nobody would cross the border freely again.

Michael Ebert, now aged 77, lived in East Germany, to the east of Berlin. “I remember the wall going up,” he says, “but news was slow to leak out at the time because it was all controlled by the government. It had already become difficult to even approach the border with West Germany but Berlin had remained pretty much open. My family in Berlin eventually told me it had gone up. I wasn’t surprised. My small town Furstenwalde had been drained of young people fleeing to the west. It was a meagre existence. I knew the government would stop them one way or another.”

Eventually, blocks replaced the temporary barriers, houses right on the border were bricked up (especially after West Berliners arranged to hold blankets beneath windows so escaping East Germans could jump safely) and their residents were moved out, although for a short while they were common routes of escape.

Volker Baumann, now 89, lived in East Berlin when the wall went up. “I had a friend who had one of the houses right on the route of the wall,” he recalls. “The front door was in East Berlin, the back door in the west. It took a few weeks before the authorities put a stop to it, but we really could walk through the house into the west, and come home again after seeing friends. I recall my friend’s father who lived with him saying every time we walked through ‘the price of transit is one shot of schnapps, please pay up’. Then, of course, the border guards bricked up the back door. And later they moved my friend out of the house completely and demolished it.”

In some cases – Bernauer Strasse being one – the barrier ran down the centre of the street. Neighbours could peer over it until the wall got too high and later those on the eastern side were moved away. Day after day the wall, or Die Mauer in German, rose higher, until it was topped by a horizontal concrete water pipe to create an overhang with the intention of making climbing it more difficult.

Guard towers were erected and, eventually, the area on the eastern side of the wall was cleared to create what became known as the “death strip”. Electrified tripwires, dog runs, tank traps, anti-vehicle trenches, spotlights and a shoot-to-kill policy ensured that very few people would attempt to cross it. Nonetheless, some did.

Why was the Berlin Wall built?

A timeline, 1945-1961

1945 | By April, Soviet troops have reached Berlin. A month later, Nazi Germany surrenders, effectively bringing the war in Europe to an end. From June to August, the Potsdam Conference takes place. The Allied victors divide Germany and Berlin into four occupation zones.

1948 | In June, the Berlin Blockade begins. The Soviets cut off all supply routes between Berlin and West Germany, turning West Berlin into an isolated island surrounded by East Germany. With access blocked, the Allies begin the Berlin Airlift, which keeps Berlin supplied for the next 11 months. In September, the Soviets force the Berlin city council to leave the ‘Red City Hall’ in the east sector. The communists split Berlin with the proclamation of their own ‘magistrate’.

1949 | In May, the Soviet Union lifts the blockade, but the airlift continues until September. The same month, the Federal Republic of Germany is founded, followed by the German Democratic Republic, in October. The West German capital becomes Bonn, while the East German capital becomes Berlin.

1953 | The Workers Revolt takes place in June. Workers go on strike to demand better working and living conditions, as well as free elections and unification. The Soviets help the GDR to crush the revolt.

1955 | The Allies proclaim Germany a sovereign state in May, officially ending the occupation.

1960 | In September, Walter Ulbricht becomes the head of the GDR.

1961 | In an effort to stop growing numbers of people leaving the GDR, Ulbricht orders the construction of the Berlin Wall. On 13 August, East German soldiers begin stringing barbed wire and setting up barriers, which will eventually extend 155km around Berlin. It is now a divided city.

Although Siekmann was the first fatality, the first person to be shot by border guards attempting to cross the new barrier was Gunter Litfin on 24 August. The wall was not, at that point, the four-metre-high edifice it would eventually become and Litfin chose what he thought was a weak point. He was disaffected with what was happening, was a member of a centre-right political party outlawed in East Germany and, because of the wall, saw his livelihood as an apprentice tailor in the west, along with a flat he was renting there, being taken away from him. He was shot in the head. The Iron Curtain “descending over the continent” predicted by Winston Churchill now had physical – and deadly – form.

The western powers were nonplussed, seemingly taken by surprise, although there is evidence that American intelligence got wind of the plans a few days beforehand but only told US president John F Kennedy at the last minute. Kennedy admitted later that he miscalculated, believing the wall would never be built and therefore, at the June 1961 US/Soviet Union summit in Vienna, hinting he might not oppose the construction of a barrier.

When it did appear the US and western European nations threatened sanctions and embargoes but, short of military action that could have led to rapid destabilisation of the tense detente, there was little they could do. West Berlin mayor, Willy Brandt, who would eventually become chancellor of West Germany, was especially critical of the weak western response, describing the wall as “illegal and inhuman”. “An unlawful regime has committed another injustice,” he said. “One worse than any before. The East bears responsibility.”

The west did commit more troops to Berlin but it was a symbolic rejoinder. The only response was to remain pragmatic – facing off with the Soviet Union from the small, democratic island that was West Berlin was never going to be a strategic winner either militarily or electorally, not for any US president nor arguably any German politician.

Kennedy called for calm saying that the west would not panic and “we are going to do nothing now because the only alternative is war”. Even West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer waited a week before visiting the city. Discretion was not the better part of valour, it was the only part.

And so the wall became part of the fabric of the city. It was built slightly to the eastern side of the border with West Berlin and so was wholly on East German territory. All West Berliners could do was look at it, and wave… waving became a weekend tradition as families divided by the wall could now only stand on higher ground or specially constructed platforms and signal to their relatives and friends on the other side. And because West Berliners could walk right up to the wall on their side and touch it, it became a graffiti-ridden protest zone even attracting tourists to such famous slogans as “There is life behind this wall” and “The world is too small for walls”. Murals too featured and artists such as Thierry Noir became famous for their political works on the wall.

Strangely, because the wall was slightly in East German territory, every once in a while guarded maintenance workers would emerge through one of the few doors and paint over the graffiti before returning to East Berlin. Some western graffiti artists were even pursued by guards coming through the doors, especially East German defectors returning to paint slogans. Four were dragged back through the wall in 1986 and, despite western protests, no international boundary had been crossed by the guards. Perhaps even more strangely, occasionally East Germany would sell sections of the territory near the wall to West Germany to raise hard currency.

By the time the wall was complete, it was more than 150 kilometres long and surrounded West Berlin. Some sections used fencing and barbed wire but the central stretch was all concrete and was pretty much impregnable, watched over by more than 10,000 guards, some of them in the 302 armed guard towers, although later it transpired there were deliberate weak points in case tanks needed to crash through in times of war. The few doors in the wall each needed two keys to open them so everybody had a chaperone. There were only nine official crossing points, the most famous of which – for it was to feature in any number of Cold War spy movies and books – was Checkpoint Charlie.

I used to take the train into West Berlin. But the morning the wall went up, the guards had closed the station. I thought that my boss would be angry with me when I turned up the next day. I didn’t realise that I would never speak to him again

Crossing points were named after letters of the alphabet and Checkpoint Charlie was the nickname for the C crossing. It was here in late 1961 that one of the flashpoints of the Cold War, one that could have led to actual conflict, was diffused. Soviet and US tanks faced off just metres apart over whether allied personnel could legitimately cross into other parts of the city.

Fortunately, no shots were fired after Khrushchev and Kennedy sensibly diffused the situation. And while actual spy swaps between the Cold War powers were usually conducted away from such public spaces it was here that the captured American U-2 spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers, shot down in 1960, was exchanged for Rudolf Abel, a Soviet spy arrested in New York.

“I crossed into East Berlin on a 24-hour visa in 1979,” says Canadian Brian Hamilton who was a 21-year-old student in Bonn at the time. “Non-German westerners could use Checkpoint Charlie. It seemed like you were part of some immense piece of history, leaving the famous checkpoint hut in the west and crossing the gap in the wall and seeing the death strip. I was genuinely scared but excited too. I was an engineering student then and although I was allowed to walk around East Berlin and even visited a bar, I know I was followed.

“West Berlin was a showpiece city, deliberately glitzy and wealthy and had theatres and nightclubs and the contrast with East Berlin was huge. It really seemed dowdy and oppressive, although I wonder if my perception was preconditioned. I did get a tram though which cost me next to nothing to travel for what seemed like kilometres.”

Trams became the most common form of transport in the east because although the Berlin U-Bahn (or underground) continued to circulate beneath East Berlin after the wall was built, the stations were bricked up and guards placed in the tunnels in case defectors to the west chose to go under, instead of over, the wall. One of the more comical escapes came when a fugitive entered the tunnel to try to reach a station on the western side. The first guard sent to arrest him did not return, nor did the second. The third guard, this time not alone, discovered all three had defected.

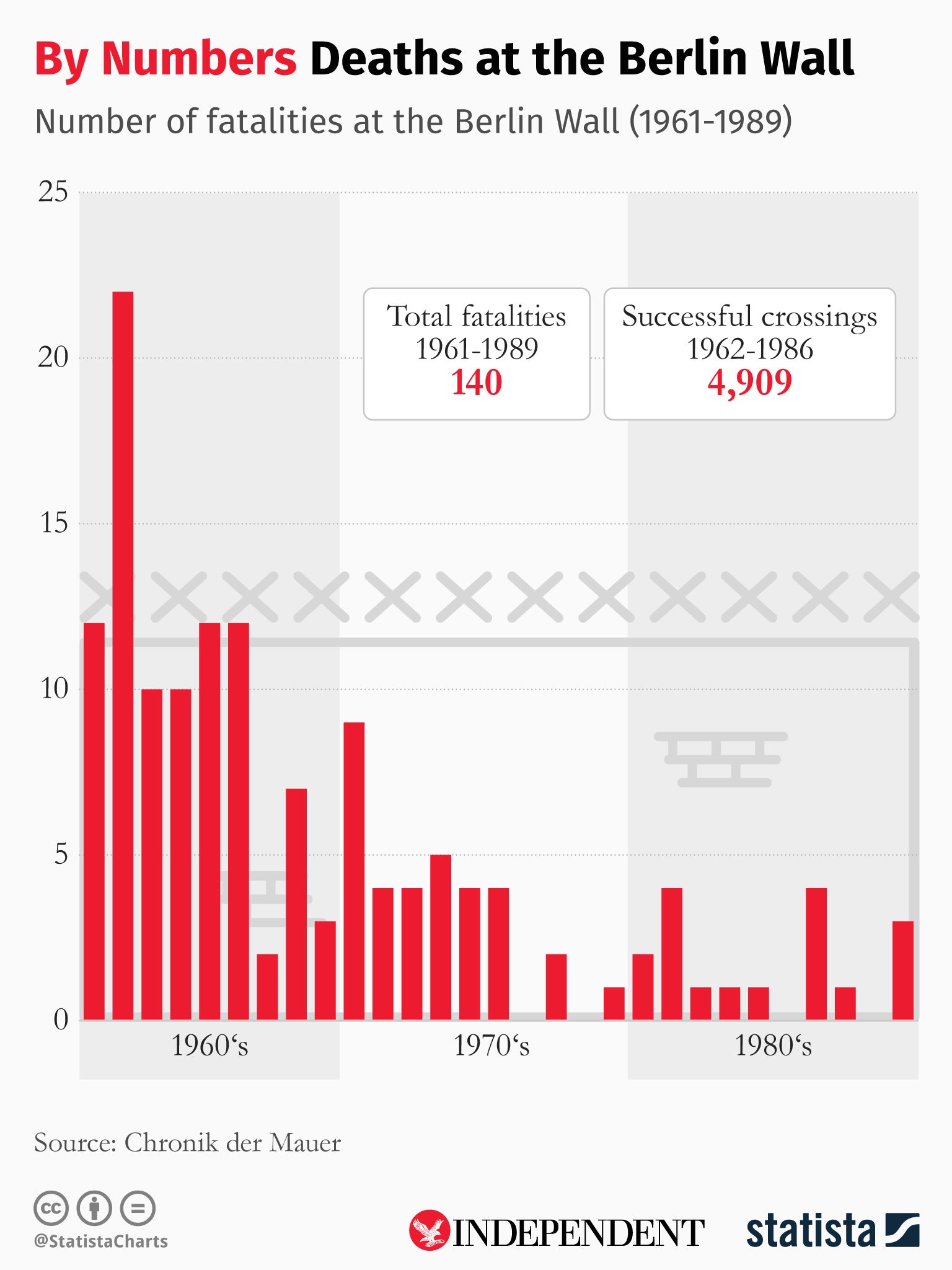

The wall stood for 28 years, a mental as well as a physical barrier to the west. And while as many as 200 people may have died trying to cross the death strip – figures are disputed and the DDR apparently did not record casualties – as many as 5,000 were still successful in making it to the west including 57 people who dug a tunnel under the wall in 1964 and trapeze artist Horst Klein who used a disused power cable as a tightrope to cross it. They were lauded in West Germany. The wall turned escapees into propaganda heroes, and those responsible for the shootings of defectors would eventually be declared murderers following the reunification of Germany in 1990.

US secretary of state at the time it was built, Dean Rusk, described the wall as a “monument to Communist failure”. If the Soviet Union and their East German colleagues believed the wall would reduce the resolve of the western allies to protect and support West Berlin they were mistaken. It was the manifestation of the Cold War in the 20-centimetre width of a single concrete block and a public relations disaster – the traumatic bleeding to death of Peter Fechter in the death strip in 1962 and the shooting of two children in 1966 being two especially egregious incidents – becoming a recurring stain on the facade of East German socialism. As a symbol of an ideology gone wrong, it has no equal anywhere in the world. But it was to endure for three decades before its fall, 30 years ago this month.

“Our lives and travel were very much restricted before the wall fell,” says Ebert. “The ironic thing was although I lived in the DDR, the first time I ever saw the wall was after it had been pulled down, in a museum.”

And as for Schumann, his fame and the immediate loss of contact with his family, friends and colleagues would weigh heavily on him. Even after the wall came down he was reluctant to visit, feeling he had more in common with Bavarians in whose state he had settled. Confused, depressed and with feelings of guilt, he took his own life in 1998.

Infographic provided by Statista

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks