From the Independent Archive: Our 1989 coverage of the key events that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall

Marking 30 years since the fall of the barrier that divided east and west, we look back at how Independent reporters bore witness to one of democracy’s greatest triumphs

To meet, he is like a dowdy little bird with shy, black eyes that give nothing away. In public, he is always dressed in an anonymous coat whose cut has that wilful, in his case expensively-tailored, ugliness favoured in the German Democratic Republic. You could easily lose him in a crowd of pensioners queueing at the Alexanderplatz crossing to visit relatives in the west. Such economically useless people have been allowed to go as they please since 1964, foot soldiers in the class war against “the imperialist, revanchist west”.

At 77, the East German leader, Erich Honecker, does not look or sound like a ruthless tyrant, still less the object of an 18-year-long cult of personality. He is said to be dying, or even dead. He is certainly very ill after a gall bladder operation, and conspicuously silent about the this week’s great exodus of East Germans through Hungary.

Since 1985, his position and the very existence of the state he governs has depended on a Soviet Union whose leader patently does not like Honecker and is, apparently, prepared to reopen the German Question. The elaborate nonsense of the GDR is coming unravelled and with it the economic support of West Germany on which it has depended for more than a decade. As his doctors in East Berlin try to keep Honecker going long enough to take part in the fortieth anniversary of the GDR on 7 October, the piquant absurdity of his position becomes ever more apparent.

He is quintessentially ordinary, a petit bourgeois figure known to enjoy a game of scat, beer and a palatial complex on the Wandlitz lake 25 miles from Berlin. Nearby he keeps a former royal hunting lodge. Foreign guests on shooting parties have been taken aback by the way rabbits and deer are chased on to specially-prepared clearings so they have no chance of escape. Like his late friend Leonid Brezhnev, Honecker enjoys the fruits of having history on his side.

His working-class and communist credentials are impeccable. He grew up in harsh poverty as the third son of a militant communist miner in the grimy village of Neunkirchen in the Saarland, now part of West Germany. He imbibed the dream of a workers’ paradise while his schoolmates read Grimms’ fairy stories. A Young Pioneer at the age of nine, a full member of the Communist party at 17, he is almost the last of the pre-war school of illegal, persecuted Communists.

He still retains the pretensions he always had to being an ordinary working fellow. He calls his servants by the familiar “du” and encourages them to do the same. Few European communist leaders, apart from Nicolae Ceausescu of Romania, can be quite so remote from their people.

His is a dourly intolerant face, but a sentimental one, owing much to the dreadfulness of early life in Neunkirchen, famous in the Thirties as “the Red village”. A mediocre student, he left his (Protestant) school at 14, laboured on a farm in Pomerania and then returned to train as a roofer. But from 16 onwards he was a full-time party functionary. Arrested in 1935 and sentenced to 10 years for “preparing to commit an act of high treason”, he spent the war in the Berlin concentration camp prison of Brandenburg-Görden. When he emerged in 1945 it was with a world view that has not changed since.

Three years ago he returned to his birthplace. Received as a head of state, he made the obligatory visits to Karl Marx’s birthplace in nearby Trier, and to his only surviving sibling, Gertrude, wife of a tram conductor. It was all attended by great pomp and sentimentality. For a few minutes wishful exegesis prevailed when he remarked: “The day will come when borders don’t divide us but unite us, as does the border of the GDR and the People’s Republic of Poland.”

When the fuss died down, it was clear it meant nothing except what he had said ever since he became leader in 1971: that the GDR wanted full recognition from West Germany, including, crucially, that of its GDR citizenship. More recently he has said the wall might stand for 50 to 100 years. Since he came to power he has extirpated references to “Germany” and “The German nation” from the constitution. Honecker is well aware that a state based purely on ideology is absolutely dependent on the continued ideological division of Europe.

His rise to power after 1945 was swift. He was put in charge of youth organisations by Walter Ulbricht, who had spent the war in Moscow, and was leader of the fledgling Socialist Unity Party and was to become East Germany’s First Secretary.

Honecker’s monomania took him onwards and upwards. As head of party cadres in 1963 he could fill all the key posts with his allies. With his wife Margot number two in the Education Ministry, he could even risk an attack on Ulbricht for his “liberalism” at that year’s party congress.

By 1971, when Ulbricht was becoming too uppity for Moscow, Honecker was the obvious successor. His avuncular style appeared refreshing after the sour bureaucrat Ulbricht. In the years that followed, Honecker managed to attain a mild popularity.

There were no taboos in art and literature, he announced at the party conference a month after Ulbricht’s fall, though he soon changed his mind. More crucially, it was going to be jam today “We know only one goal,” he said. “It permeates the whole politics of our party – to do everything for the good of the people, for the happiness of the people, for the interests of the working class and all employees.”

With his population securely locked in by the wall and border fences, Honecker could offer the consolations of more flats, better child care, maternity benefits and a standard of living which was enviable by eastern bloc standards.

Behind it all lay the “Basic Agreement” negotiated with the Social Democrats in Bonn, which came into force in 1973, and from which flowed an ever-growing tide of billions of deutschmarks, the much freer travel between the two Germanys and other concessions Bonn wanted in return.

When the Soviet Union refused to help the GDR to maintain its relatively splendid standard during the Seventies oil crises, Honecker quickly saw there was no shadow of a parting from his incestuous relationship with West Germany. But it has not been enough. The comparisons constantly held up by West German television – seen by absolutely everybody – and the eyewitness evidence of visitors, proved in the end fatal.

Seeking legitimacy on another level, Honecker tried to present the GDR as not only the good but somehow the real German nation. Frederick the Great became “the enlightened Prussian monarch”. In 1983, on the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s birth, it turned out he was an early Marxist. Bach, Beethoven, Wagner, lately even Bismarck have all been roped in and dressed up, as the formula has it, in “Socialism under the colours of the GDR”.

The colours are, alas, the same as those of West Germany whose legitimacy and prosperity are built on sturdier foundations and to which more than three million East Germans have fled, or perished in the attempt.

Much as it is now maligned, Bonn’s longstanding policy of “small steps”, inaugurated by Chancellor Willi Brandt, was without doubt instrumental in bringing about the present debacle. The other key factor, apart from the changes in the Soviet Union, Hungary and Poland, is demographic. The younger generation, lacking any experience of Nazism or Stalinism at its worst, is no longer afraid. Moreover its values are, much as in West Germany, individualist and consumerist.

It always fills me with satisfaction when experts and politicians from the western world agree with us what a positive contribution was made to peace and detente by the ... building of the wall in 1961

If Honecker’s memoirs give little about him away, nor does the communist style of personality cult. The impression of foreign politicians is of neither a great mind nor an especially tough character.

Heads of the West German permanent representation in East Berlin tend to emphasise Honecker’s bonhomie. “It would perhaps astonish him, a man who loves the aura of a liberal father figure, that many people in his country hold him responsible for the brutality of the state apparatus,” said one. Another said crisply: “He likes to be in a small group all agreeing with each other, but one has to say agreement must be in the tone of voice he determines.”

Improbably, Honecker is said to be an enthusiastic womaniser; his two marriages look rather like alliances of political convenience. The first, to the deputy head of the German Youth Movement (FDJ), ended in divorce. The second was to Margot, then head of the FDJ. She is a power in the land, a still beautiful and forbidding zealot given to speeches of stunning tedium about the need to remember the class war. They are said by a defector to quarrel quite a lot, and Margot to have the upper hand. Honecker has daughters by both marriages, and several grandchildren.

His proudest moment was undoubtedly the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961. It was not his idea, rather Ulbricht and Khrushchev’s, but he carried it out and it was clearly the precondition of the GDR not bleeding to death. It will be Erich Honecker’s memorial, and earn him a footnote in history. Honecker says of it: “It always fills me with satisfaction when experts and realistic politicians from the western world agree with us what a positive contribution was made to peace and detente by the measures of August 13 1961.” Socialists need achievements, it is a key word.

But Honecker’s most recent justification of the ugliest frontier has been given point by this week’s exodus. Last June he said: “No one can be in favour of the restoration, in the heart of Europe, of a state which is hard to control.” It is a point giving pause for thought in all the capitals of Europe, as well as in Washington and Moscow.

Comment section profile of Erich Honecker, 16 September 1989

Honecker forced out by East German protest

East Germany’s ruling Communist Party agreed yesterday to retire its veteran leader Erich Honecker, 77, following mass emigration and huge demonstrations for political reform in recent weeks. His successor was named as Egon Krenz, 52, the country’s security chief, who has been seen as a protegé of the hardline Mr Honecker. Günter Mittag, in charge of the economy, and Joachim Herrmann, responsible for the media, were also sacked. In a debut speech broadcast last night, Mr Krenz criticised the party’s past insensitivity, and expressed sympathy with families divided by emigration.

“It is clear we have not realistically enough appraised social developments in our country in recent months and not drawn the right conclusions quickly enough ... All of us can feel the tears of the many mothers and fathers,” he said. Less than a month ago East Berlin said in a statement it would not waste tears on the emigrants.

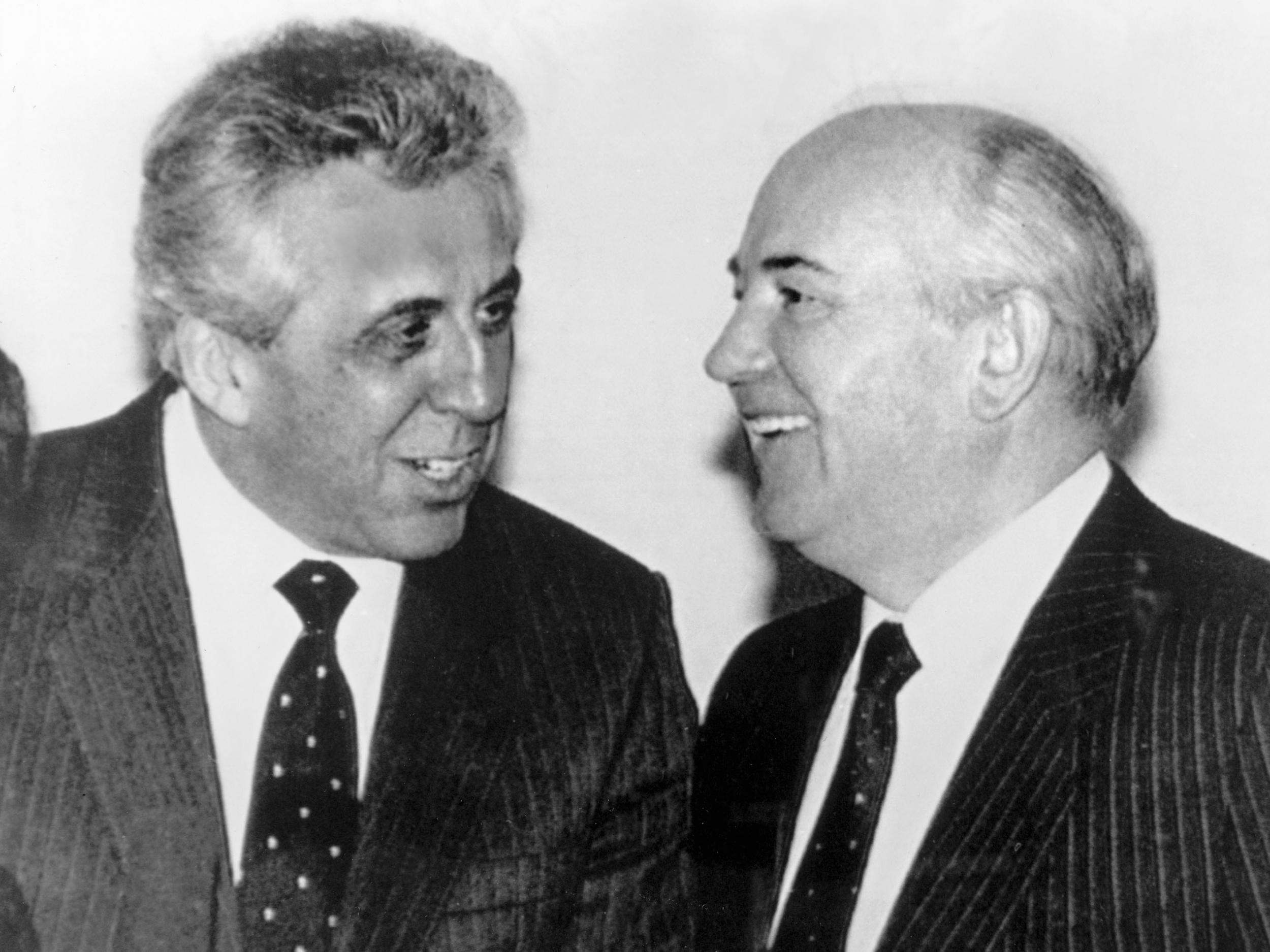

Mr Honecker’s removal, though described as being at his own request, because of poor health, marked the first time that popular pressure had brought down an East German leader. President Mikhail Gorbachev sent his congratulations to Mr Krenz, and expressed confidence that the new leadership would find the solutions “so necessary to the complex problems of the country”. But the New Forum opposition group said it was “improbable” that Mr Krenz would introduce reform.

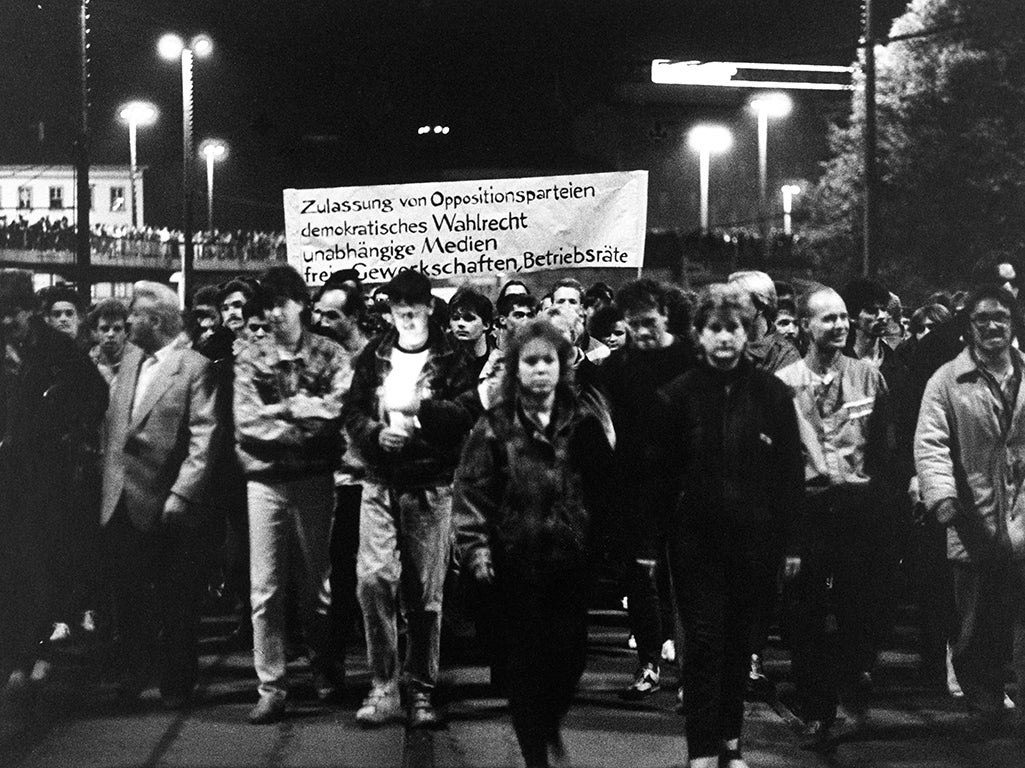

The pressure for change in the party had peaked on Monday, when more than 100,000 protesters marched peacefully through Leipzig, chanting “Gorby, Gorby.” It has since been suggested that it was Mr Krenz who ordered that police should not use violence against the Leipzig demonstration. But it is none the less unclear whether the GDR’s new leader can continue to allow protests to escalate indefinitely.

Opposition solidarity in East Germany has grown wider and stronger in recent weeks, and the government can no longer even count on support from Warsaw Pact neighbours if it resorts to violent repression. If, however, Mr Krenz allows pressure for change to grow, the very long-term existence of the East German state seems certain to be called into question.

Meanwhile, as a vivid reminder that nothing anywhere in east Europe could be taken for granted any longer, a Polish government spokeswoman said in Warsaw yesterday that the Solidarity-led government was seeking an end to the post-war division of Europe by the superpowers into “spheres of influence”: only one step short, apparently, of declaring UDI from the Warsaw Pact. It goes well beyond Mr Gorbachev’s cosy talk of a common European home.

Steve Crawshaw, 19 October 1989

East German MPs show a tiny bit of independence

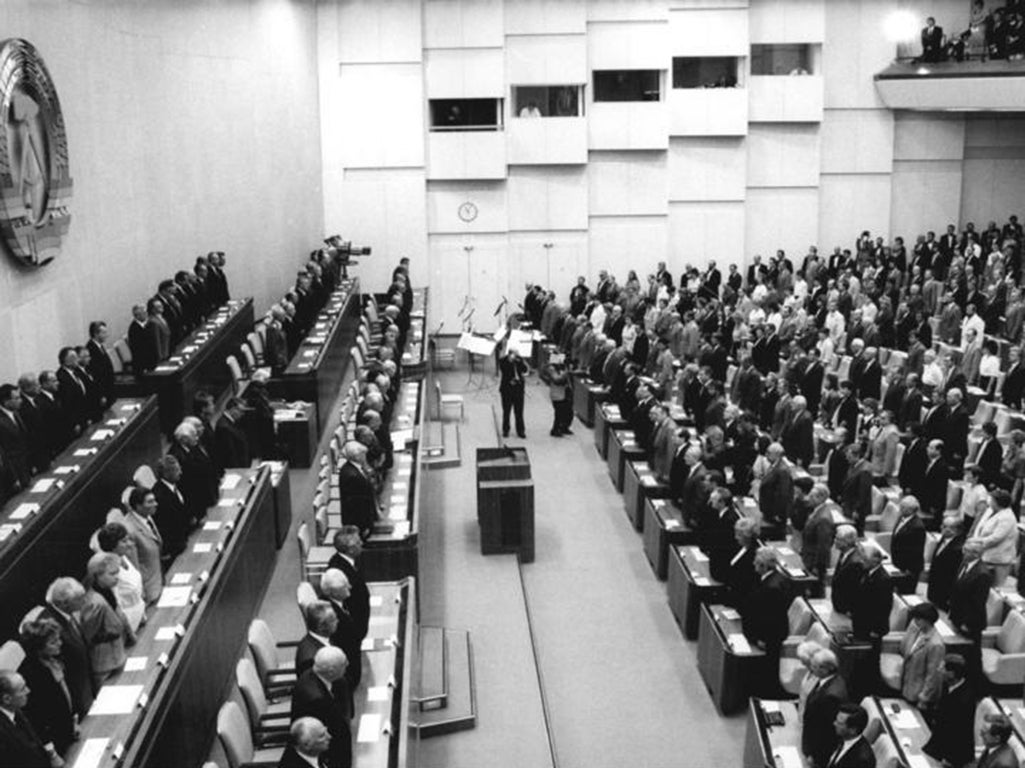

East Germany’s parliament, the Volkskammer, stirred out of its 40-year sleep yesterday when 10 per cent of its members refused to vote for Egon Krenz, the new leader, as head of state. Twenty-six members of the newly-assertive Liberal Democrat and Christian Democrat parties and a handful of other hitherto subservient non-communist groups voted against him and a further 26 abstained. A stir arose in the chamber. It was the first time that any of its 500 members had ever opposed the Communist Party’s choice of leader and only the second time anyone could remember that members had dared say no at all. Catholic members unsuccessfully opposed an abortion bill in the 1970s.

Predictions that the dissidents would put up their own candidate or force a debate on current issues proved false. Impassive faces and dutiful clapping in the austere parliament chamber indicated that gestures of independence were going to be carefully measured.

Mr Krenz, now head of the party and head of state, continued to woo the support of his people by expressing regret for police brutality during recent demonstrations and promising moves to give the rubber-stamp parliament a more active role. He spoke frequently and warmly of the “dialogue” that was needed to solve East Germany’s problems but made it even clearer than before that he was not planning any reforms that would reduce the party’s hold on power. “Nobody should draw the wrong conclusions from the developments in the German Democratic Republic,” he said. “Suggestions that we reform socialism out of existence here have no hope.”

But only a few hours later some 6,000 East Berliners gathered round the door of the Volkskammer, then marched through the streets demanding free elections. One group bore a banner calling for the fall of the Communist Party. Some had demonstrated the night before to demand that the parliament elect someone other than Mr Krenz because they objected to such a concentration of power in one man. Aware that many East Germans have been deeply shocked and angered by violence against people arrested during demonstrations earlier this month, Mr Krenz said: “It is regrettable that in some demonstrations it came to blows... we should try through all forms of dialogue to ensure that it does not happen again.”

He promised that anyone who had been treated unjustly or humiliated could resort to law. The justice authorities would “conscientiously examine complaints and – when there is proof – punish wrongful behaviour”. The State Prosecutor would hand a report to the leadership and the public would be informed of its contents.

He cautioned, however, against further demonstrations, which he said ran the risk of “ending differently from the way they began”. The “new democratic spirit” in East Germany would be reflected in the Volkskammer itself, which he said should be “our people’s highest organ of power”. Members would take an active part in preparing laws and supervising their enforcement: “Legislation cannot be limited to the approval ... of government proposals.”

He proposed that a parliamentary committee be set up to deal with the environment – a remarkable departure after years in which the government pretended East Germany did not have serious environmental problems. The mass media would in future be able to report quickly and fully about the activities of parliament, its committees and members. Mr Krenz made no mention of free and secret elections but said that protests and comments about past elections – presumably referring to complaints about systematic rigging – would be looked into and “if necessary be taken into consideration in electoral law”.

Patricia Clough in East Berlin, 25 October 1989

East Germans awake to new media freedom

From 7.30 each evening, millions of East Germans sit riveted to their television screens, hardly able to believe their eyes. The attraction is not some western spectacular but their own evening news programme, Aktuelle Kamera. For decades, Aktuelle Kamera has been churning out a mind-numbing diet of production figures, visits by dreary apparatchiks from other eastern bloc countries and communist propaganda. Now, camera teams are out filming demonstrations, reporters thrust microphones in front of party leaders, workers and students are seen grumbling freely about everything wrong with the country. “It’s fascinating,” said one government official incredulously. “It’s much better than watching the West German news.”

And this is not all: later in the evening viewers may get a live phone-in where politicians must find quick answers to highly critical questions from the public, or a panel discussion between opposition figures and senior party officials. And, for the first time, East Germans are avidly reading their own press. Newspapers sell out by mid-morning. Pages are filled with interviews or readers’ letters in which a whole population, it seems, is pouring out all the pent-up bitterness of 40 years.

Even the official party organ, Neues Deutschland, is beginning to unbend, with reports of criticisms and, for the first time, accounts of what went on inside Politburo and Central Committee meetings. “It is quite a problem,” one East German politician joked to The Independent. “I used to be able to skim Neues Deutschland on the way from my house to my garage every morning. That was all I needed. Now I have to spend hours reading the papers to know what is going on.”

This explosion of freedom in East Germany’s media is one of the few tangible changes so far amid the many nebulous promises of the leadership. “Dialogue” is the order of the day. Egon Krenz, the new leader, evidently hopes that this chance to let off steam will ease the pressure from demonstrators, opposition groups, workers’ collectives and even the party grassroots itself, for whom freedom of the press along with freedom to travel has been one of the most urgent demands.

He also hopes that open discussion might give the party ideas for solving the country’s problems without the need to reform the system itself. Many East Germans and foreigners are doubtful.

One of the first moves the Politburo made, apart from electing Mr Krenz to succeed Erich Honecker, was to ditch Joachim Herrmann, the party boss responsible for the media. “It’s not all that long ago that reports in one of our papers about hunger in Romania were censored because they were deemed to be offensive to a fraternal country,” said an official of the Protestant church, whose publications also suffered from Mr Herrmann’s heavy hand.

The new freedom has caught East German journalists untrained and unprepared. “We were taught in journalism school that the western press, particularly the West German press, was bad,” said Hans-Jörg Heims, a political reporter on Der Morgen, the organ of the newly-assertive Liberal Democrat party. “We used to receive instructions from the party, the Interior Ministry and the Foreign Ministry as to what we should say.” Now, so for as he knows, there are no restrictions.

“It’s much harder work now and much more difficult,” says an older journalist from the official news agency ADN. “Reporters have to think for themselves, they have to get out of the office and talk to people. Many are not used to it.”

ADN journalists were abused and insulted by factory workers for misrepresentation. One of the first stirrings came when the staff refused to describe peaceful demonstrators as hooligans. “Until now journalists have been rather despised in society here. We were regarded as a minor arm of the party,” said Mr Heims. So far change is limited mainly to publishing complaints in interviews, speeches and letters, still interspersed – especially on Aktuelle Kamera – with liberal doses of propaganda. Further change will clearly take time. But there have been many heated arguments in editorial conferences, the ADN man said. “Things will move on. This is only the beginning.”

The mayor of Leipzig, Bernd Seidel, announced he was quitting by confessing that he had “lost the confidence” of local citizens. Another prominent trade union leader also lost his job: Herbert Bischoff, for 19 years head of the artists’ section of the main union federation, the FDGB. A small party allied to the communists, the Liberal Democratic Party, yesterday called for the resignation of the entire government.

Inside the Prague embassy, the 18th century Lobkowitz Palace which was once the home of a prince of Bohemia, the refugees were crushed into drawing-rooms designed for the comfort of a few dozen diplomats. Ornately decorated salons bulged with triple-bunked army beds, packed so tightly that only the most determined of fresh arrivals could squeeze a way through. The temporary occupants sardined themselves two or three to each mattress. Broad staircases were submerged beneath sleeping bags. Hundreds of children played, cried and cuddled favourite toys.

More than 167,000 East German refugees have poured into West Germany so far this year. Perhaps 190,000 will have gone by the end of the year.

Patricia Clough in East Berlin, 27 October 1989

Biggest march yet in Leipzig

Unimpressed by new travel laws, the biggest crowds yet seen in Leipzig, Dresden and other East German cities last night marched through the streets demanding free elections and an end to communist domination. In Leipzig, church sources estimated that half a million people were braving driving rain in the biggest-ever demonstration in the grimy industrial city, the chief centre of opposition to the regime. It came second only to the vast demonstration of about one million people in East Berlin last Saturday.

Hundreds of thousands more were on the streets for the first time in Dresden, among them the reform-minded local party leader, Hans Modrow, and the city’s mayor, Wolfgang Berghofer. “I have never seen such a mass of people in my life before. It’s crazy what’s happening here,” one eyewitness said. Another 60,000 marched in Halle, 50,000 in Karl-Marx-Stadt and 25,000 in Schwerin.

At the same time the number of East Germans who have emigrated illegally to West Germany since Czechoslovakia began letting them out on Friday rose to 23,500. The demonstrations and the renewed exodus showed that attempts to placate the public with (somewhat) easier travel, freedom to complain and promises of other improvements, were not enough. The right to travel, initially one of the most urgent issues, has given way, among those who are staying, to demands for a thorough reform of the system.

Bernhard Knupp, a Leipzig communist government official, speakers from the New Forum opposition group and banners everywhere called on the government to resign and make way for reformers. Chanting demonstrators and yet more banners clamoured “Free elections, free elections”, while others demanded an end to the “leading role” – or complete domination – of the Communist Party. “Egon, who voted for you?” placards asked Egon Krenz, the new leader, while others insisted “The Wall must go”. Numerous banners read “Travel laws without restrictions”, reflecting the widespread disappointment here when the long-promised travel laws were published earlier in the day. East Germans found that although they will all have a right to passports and to go abroad for 30 days each year, there are serious limits in practice.

They will still require exit visas – that is, permission to go – which must be applied for at least 30 days in advance, and these may be denied for reasons of national security, health, morale or public order, which could be stretched to cover all sorts of cases. Nor do the visas give the right to buy foreign currency before leaving, which will be at the discretion of the finance minister and will depend on how much of the country’s hard currency he is prepared to spare. Since this is in extremely short supply, East Germans are assuming that freedom to travel will be restricted, once again, to those with helpful relatives in the west or with access to hard currency.

In Bonn, government officials estimate that if travel restrictions for East Germans are really eased, between 1.2 and 1.4 million would come to the west to stay. Several West German leaders have expressed severe misgivings that such an influx would be beyond the ability of their country to cope with, in view of its serious housing shortage and 1.9 million unemployed.

Hans-Jochen Vogel, chairman of the West German Social Democrats, appealed to would-be emigrants “to think carefully whether they should not stay in the GDR and support the process of democratisation”. And Oskar Lafontaine, the deputy SPD chairman, warned: “If we ask too much of our own population, we will drive them to the [ultra right-wing] Republicans.”

An impassioned appeal for moral support for Mr Krenz was made yesterday by the vice-president of the European Commission, Martin Bangemann, who argued that it was essential to generate confidence in Mr Krenz’s reform efforts. “It is a good idea to support the reforms, even if we know that they are not going to lead to the total democratisation of East Germany,” he said.

The European Community’s foreign ministers decided, however, to continue to watch developments in East Germany rather than take immediate action in offering preferential trade and cooperation agreements.

Patricia Clough in Bonn, 7 November 1989

The East German cabinet quits

The East German government yesterday yielded to pressure from vast demonstrations and the rapid haemorrhage of its young people, and resigned to make way for change. Shortly afterwards the Communist Party’s Politburo – the real organ of power – gathered to decide on its own fate, while outside hundreds of thousands of demonstrators were chanting: “All power to the people, not to the party!”

Egon Krenz, the country’s new leader, announced recently that five more of the 21-strong Politburo had asked to go, in the wake of the three – including his predecessor, Erich Honecker – who have already resigned. But as the lights burned late in the stern grey building in the city centre, expectations rose that they would all go soon.

The announcement that a government had resigned for the first time in East Germany’s 40-year history carried no explanation. It was accompanied, however, by an appeal to the population “to ensure in this grave political and economic situation that all services that are vital to the people, to society and the economy are maintained”. It was also in their interests to maintain public order, the appeal added.

The government called on East Germans who were planning to go to West Germany to think again: “Our socialist fatherland needs each and every one of you.”

The way the announcement was made was also epoch-making: at a press conference by a government spokesman, neither of which East Germany had ever had before. The new spokesman, whose appointment was announced only a couple of hours earlier, is Wolfgang Meyer, hitherto head of the Foreign Ministry’s press department. After reading the statement, however, he declined to answer any questions.

The dizzying speed of change in East Berlin appeared to have no effect on the determination of vast numbers of East Germans to leave. They were pouring out through Czechoslovakia at the rate of 9,000 a day, or an average of 375 an hour. Some 30,000 have come since Czechoslovakia opened its border on Friday, filling the reception camps in southeastern Germany to overflowing, and causing serious concern to the government in Bonn, which fears the country will not be able to absorb such numbers?

The East German Communist Party’s Central Committee starts a crucial three-day meeting today, at which it will elect new members to the Politburo and thereby, through its choice, set the political course for the future. The 45-strong cabinet, however, is elected by the parliament, the Volkskammer, which may be convened for a special session some time next week.

The ministers will carry on in office until their resignations have been accepted and their successors chosen. The government in East Germany does not enjoy the same powers as its equivalent in the west. It is more an executive body which carries out decisions made in the Politburo. But the Volkskammer is shortly to be given wider powers and is in any case beginning to assert itself after 40 years of passivity, so it appears likely that the government could become much more independent.

The resignation looks like the end of the road for the 75-year-old prime minister, Willi Stoph, one of the first and oldest of the “old guard”. Trained, like many of East Germany’s Stalinist leaders, in political and military schools in the Soviet Union, he was sent in after the war to turn the Soviet occupation zone into a communist state. For 40 years he has held top party jobs and has been prime minister for 22 of them.

It was the first time a government had resigned in East Germany’s 40-year history. And it was in their interests to maintain public order. An appeal went out: Our socialist fatherland needs each and every one of you

His government’s departure was only one of a series of events which followed each other with staggering speed. The constitutional and legal committee of the Volkskammer virtually threw out the new travel laws which the government had presented only the day before, saying they were “not acceptable”.

It demanded the abolition of the exit visa, or official permission to travel, which was retained in the law, even though it was supposed to give East Germans more freedom to travel. It insisted that the government must think again about only allowing people to go abroad for 30 days a year, and about clauses which enable it to prevent certain categories of people going at all.

Not content with just that, it also demanded an immediate session of the Volkskammer, and protested publicly that the Volkskammer’s president’s office had ignored such demands, even though they had been backed by the required number of members.

The prospect of multi-party elections was held out by the liberal-minded mayor of Dresden, Wolfgang Berghofer. In an interview with Le Monde, Mr Berghofer said that the leadership was working on a new electoral law “whose main feature will be that one has the choice between several candidates belonging to different parties. There will also be a completely transparent system for counting votes so that there can be no suspicion of manipulation.”

Mr Berghofer did not specify whether this would just mean parties which already exist, or whether new, independent ones would be allowed. Until now East German voters have always been presented with no-choice lists composed of candidates from the Communist Party and its four small satellites. Civil rights and church groups – which monitored counting during municipal elections this year – found that the results had been rigged.

Patricia Clough in Bonn, 8 November 1989

Berlin Wall breaks open

East Germany last night decided to throw open its heavily-fortified “iron curtain” border, including the Berlin Wall. Soon after the announcement was made at 6.55pm local time, East Germans on foot and in cars had begun arriving in the west. One couple crossed the Bornholmer Strasse checkpoint into West Berlin at 9.15pm, their identity cards stamped with new-style visas. Later, hundreds more were seen coming by way of the Friedrichstrasse underground station. Unusually, others were allowed to come in through the military-run Checkpoint Charlie. Many apparently came even without visas, although these were technically necessary under the new regulations.

Chancellor Helmut Kohl, on a state visit to Poland, told West German television that he wanted talks with the new East German leader, Egon Krenz. “We will be in contact with the East German leadership shortly after my return,” he said, “and I would like to meet very soon with Mr Krenz.” Asked how many refugees West Germany could absorb, Mr Kohl said: “We shall have to wait and see how many actually come.” He added that it would be in West Germany’s interest for East Germans to “stay at home”.

President George Bush said he was elated with the decision, calling it “a dramatic happening”.

The announcement struck West Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag, like a thunderbolt. A debate about taxation erupted into ecstatic applause. An impromptu rendition of the third verse of the national anthem – “unity and law and freedom” – filled the chamber. Many parliamentarians called for the immediate destruction of the Berlin Wall, built in 1961.

The mayor of West Berlin, Walter Momper, said: “This is the day that we have been waiting for for so long. The border will no longer keep us apart. It is a day of happiness for Berlin.” Eberhard Diepgen, a Christian Democrat, declared “the dawning of a new era. The wall has lost its meaning. It can and must be torn down.” But Günter Schabowski, the East German Politburo media chief who announced the open border, said that the wall would remain standing, for the time being, for military reasons. It was needed to “ensure peace”, pending a change of attitude by Nato towards the east

The demographic implications of the decision to open the border may prove immense. Some 1.3 million East Germans – out of a population of 16.6 million – had already applied to emigrate to the west. With 200,000 having left East Germany this year alone, the army has been brought in to maintain public transport, food deliveries and hospital services.

In West Germany, an Interior Ministry official promised last night that no one would be turned back from the east. But some West Germans now fear that potential problems of jobs and accommodation could provoke a right-wing political backlash. In Berlin, Mr Schabowski said that the opening of the border was an interim solution, adopted by the outgoing government pending legislation by the Volkskammer, or parliament. The Volkskammer is to be reconvened on Monday to debate the upheavals.

The East German move has followed weeks of huge street demonstrations and calls for political reform. Though Egon Krenz, the new Communist Party chief and head of state, hinted at forthcoming “free” elections on Wednesday, he dampened hopes yesterday by adding that he was “working on the basis that our elections are already not unfree”.

Party officials have said that the process of formulating a new electoral law still has to take place, and that all sectors of society will be consulted, including the New Forum opposition group. The East German Communist Party may re-examine its policies and constitution more fundamentally next month. The Central Committee, meeting this week in Berlin, yesterday announced that a party conference would be held on 15-17 December. On Monday, the Volkskammer will elect a new government to replace the one that resigned on Tuesday. It is expected to back the Politburo’s proposal of Hans Modrow, the country’s most prominent liberal, as prime minister.

Mr Modrow yesterday addressed the Central Committee, strongly criticising its past record and presenting ideas for economic reform. These included decentralisation of the economy and more incentives for workers.

Patricia Clough in East Berlin, 10 November 1989

Bulldozers move in to breach Berlin Wall

Amid a cloud of dust and the cheers of the watching crowd, the first piece of the Berlin Wall crumbled easily under the jaws of East German bulldozers last night. Bystanders scrambled for pieces of the rubble to keep as souvenirs as border guards opened new crossing-points for the hundreds of thousands of East Berliners who have swarmed to the west for the first taste of freedom in 28 years.

The sealed crossing at Glienicke Bridge, famous as the location of many east-west spy swaps over the decades, was thrown open. Others to follow will include a crossing at Potsdamer Platz, Europe’s busiest interchange before the Second World War.

A seemingly endless series of extraordinary announcements delighted Berlin yesterday. Friedrich Dickel, East Germany’s outgoing interior minister, said cross-city bus services would link East and West Berlin; and that old, defunct underground railway stations would be reopened.

In the western section of the city, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, breaking off his trip to Poland, addressed a “freedom rally” swollen by crowds of the visitors. Many who crossed from the east yesterday seemed confident that Egon Krenz, who took over the leadership of East Germany’s Communist Party last month, would keep his promises of reform. “This has done a lot for Krenz’s credibility,” said one young man as he drove his Trabant towards Checkpoint Charlie. “People now believe he means business.” As a welcoming gift from the West German government, the visitors received DM100 each.

In East Berlin, the Communist Party continued its struggle to win popular support by unveiling reforms including the promise of free elections. The official ADN news agency said: “A revolutionary people’s movement has set in motion a process of serious upheaval ... East Germany is awakening.”

It is our duty to see that stability reigns along this sensitive frontier where capitalism and socialism meet. Without stability there cannot be peace and without peace everything is brought to nought

Mr Krenz, addressing a Communist Party demonstration yesterday, said the new freedom would show that the party was sincere in its attempts to regain the confidence of the people. He said the two Germanys would “need to behave like good neighbours along this sensitive border” and that East Germany was certainly prepared to do so.

“It is our duty to see that stability reigns along this sensitive frontier where capitalism and socialism meet. Without stability there cannot be peace and without peace everything is brought to nought.” He confirmed that a party control commission would investigate allegations of corruption and abuse of office against deposed members of the old guard and promised “free elections which would send our best people into parliament”, but remained vague as to precisely how “free” the elections would be.

As the Communist Party Central Committee met for a third day in East Berlin, signs of internal tension continued to emerge. Two former leading members of the Politburo, Günter Mittag and Joachim Herrmann, were expelled for “gross violation of party rules”. Another disgraced and dismissed Politburo member, an ideologist, Kurt Hager, criticised himself at yesterday’s Central Committee meeting, saying he had to bear a deal of responsibility for the current crisis because of his continual rejection of the need for reform. “I distanced myself more and more from real life,” he said.

Professors at the Central Committee’s Marxist-Leninist Institute said they wanted an investigation that would delve beyond the recent past to examine Stalinist excesses against German exiles in the Soviet Union and Stalinist crimes in East Germany. The country’s Prosecutor-General, Günter Wendland, called for parliament to investigate charges of official corruption.

The Soviet Union praised the East German Communist Party’s decision to allow its citizens freedom of travel, but warned Bonn that it was too early to speak of German reunification. “This is a symbolic event, a wise decision in my view, because it destroys all the stereotypes about the Iron Curtain,” the Foreign Ministry spokesman, Gennady Gerasimov, said.

In Britain, Margaret Thatcher hailed the opening of the Berlin Wall as “a great day for freedom, a great day for liberty”.

Czechoslovakia welcomed East Berlin’s move. “From our side, this solution presents a very positive step to the complex solution of this problem of refugees,” the Foreign Ministry said. But when asked whether Prague also welcomed the political changes in East Germany, a ministry spokesman replied: “At this moment it is hard to say. We must wait.”

In Bonn, the West German Chancellery minister, Rudolf Seiters, summed up local feelings: “The Wall cannot last, socialism is at an end and the drive to freedom is unstoppable,” he said. Late last night trouble broke out at the Brandenburg Gate, where jubilant crowds from both sides of the city had gathered. Franz Schoenhuber, the leader of West Germany’s far-right Republican Party, began a march to the gate with his supporters, but faced with crowds shouting “Nazis out”, they were forced to turn back.

Patricia Clough and Adrian Bridge in Berlin, 11 November 1989

East Germany names liberal PM

East Germany’s Communist Party struggled yesterday to restore stability to the country’s political system by appointing a new Politburo and nominating as prime minister a liberal reformer, Hans Modrow. Günter Schabowski, a Politburo member, said the Central Committee was working on electoral reform which could “theoretically” result in the communists being voted out of power.

Egon Krenz, who succeeded Erich Honecker as party boss last month, was re-elected general secretary; he emerged from a Central Committee meeting to confront a crowd of 5,000 demonstrators, and begged for their patience. The flood of East Germans to the west reached new heights, as 350 refugees crossed the West German border each hour to bring the total number of emigrants since Friday to 48,000. In Bonn, Chancellor Kohl spoke in his State of the Nation address about the possibility of a reunified Germany.

The day began with the resignation en bloc of Mr Krenz and the party’s all-powerful Politburo, following the example of the government 24 hours earlier. It was replaced by a roughly even mix of hardliners, most of whom had been in the previous Politburo, and liberals, or at least more open-minded politicians. The Politburo, whose number had swelled to 22 in recent years, was cut back to its more normal size of 11, with five non-voting candidate members.

The election of Mr Modrow, the Dresden party chief, was seen as a message to the doubting population that Mr Krenz and the party are serious about the need for change. But at the same time, Mr Krenz has handed his potential rival a rope to hang himself: he now has the toughest and possibly the most unpopular job in the country, and if he is seen to fail, he will be eliminated as a future leader. This threat will become even greater if, as seems likely, the government is given more independence from party control than it has had so far.

The good news, as far as the East German reform movement is concerned, was the disappearance of 12 members of the Stalinist old guard, including 81-year-old Erich Mielke, head of the hated state security apparatus, Kurt Hager, the chief party ideologist, and Willi Stoph, the 75-year-old outgoing prime minister. Nine of these did not stand again for re-election but three of them, put up by Mr Krenz, simply failed to get enough votes.

Nevertheless, enough hardliners remain to reassure the Communist Party faithful – probably the majority – who do not want much change, only a few improvements. In balance, a new leadership looked like a step in the direction of reforms but it also means that East Germany still has a long and difficult way to go.

Mr Krenz opened the Central Committee meeting with a long report in which he accused “enemies of socialism” – presumably the west – of interfering in East German affairs and trying to exploit the population’s “justified demands” to destroy communism. He warned the population to be vigilant and said that the achievements of 40 years should not be gambled away irresponsibly. He then launched into extremely sharp criticism of the old guard, of which he does not evidently consider himself a member any more, for failing to see the crisis in the country and not acting soon enough. It had failed to draw the right conclusion from what was going on in the Soviet Union and had estranged itself “from our best friend”.

While the Central Committee was meeting, some 5,000 communists held a demonstration outside calling for a congress to clear up the mess in their crisis-ridden party. Speakers attacked their own leadership for its mistakes and demanded internal democracy. Mr Krenz came out to beg them for patience and understanding. He was met by boos and whistles as well as cheers.

Mr Schabowski, who is responsible for the media in the Politburo, said the Central Committee would propose an election law to allow all political groupings with the right credentials to participate. “If we have an electoral law that allows all political forces to announce their programmes and defend them, then the SED [Communist Party] will accept the challenge,” he said. Asked if this meant that the party could be voted out of power, he said: “Theoretically that is possible.”

From Patricia Clough in East Berlin, 11 November 1989

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks