The Berlin Wall bricklayer whose death became instrumental in its destruction

The fatal shooting of Peter Fechter created a simmering fury that was only becalmed when, on an astonishing night 30 years ago, Berliners tore down the despised wall with their bare hands. Mick O’Hare remembers the tragedy that kickstarted it all

Gruesome is probably the most apposite word to sum up the death of Peter Fechter. Alongside, perhaps, cowardly. Fechter died at about 3pm on 17 August 1962 at a point near Zimmerstrasse in East Berlin. At least that’s when he stopped screaming. He was the 27th known person to die trying to cross the Berlin Wall.

The wall had been built a year earlier in August 1961. After Germany had been partitioned into four zones by the victorious allies at the end of the Second World War, two nations had been created. The Federal Republic of Germany (the FRD or West Germany) was born out of the British, American and French-administered zones while the communist state of the German Democratic Republic (DDR or East Germany) had been created from the Soviet Union’s zone. Berlin was wholly within the DDR but it too was divided into four, leaving a tiny exclave of West Germany inside the east once more formed from the British, American and French zones of Berlin.

And this was proving to be a headache for the East German authorities. People in East Germany were fleeing en masse to the west, tempted by its freedoms and living standards. Between 1949 and 1961, 2.7 million East Germans had fled to the west, most of them young and educated. And while the oppressive DDR stiffened up the border between East and West Germany, Berlin was proving to be a safety valve that wasn’t easy to shut off. Essentially you could defect from east to west simply by walking down the street – by 1961, nine out of 10 defectors were fleeing through Berlin. The order was given to build the wall.

The first person to die attempting to cross was Ida Siekmann, who was fatally injured jumping from a window into West Berlin nine days after the wall went up on 13 August. The first person deliberately killed by border guards was 24-year-old Gunter Litfin, who was shot in the head as he ran across railway tracks towards the west on 24 August. More would die in the following months as the wall became ever more fortified, guarded over by watchtowers and with the notorious "death strip" running alongside the eastern edge of the wall – spotlit and covered with tripwires and anti-vehicle traps. The outside world watched appalled and impotent.

The wall would eventually fall in 1989 but 27 years earlier one event had brought its singular horror into the front rooms of people watching around the world and, maybe with hindsight, was the first step towards its demise. The death of Peter Fechter shocked the planet. Egon Bahr, secretary of state between 1969 and 1972 to former West German chancellor Willy Brandt (who was mayor of Berlin at the time of Fechter’s death), said: “You can draw a direct line from the moment of Peter Fechter to the moment where the oppressive part of Germany collapses.”

Fechter was 18, the only boy of four children, and a bricklayer in East Berlin. His sister Lieselotte had moved to West Berlin before the wall was built and Peter rued missing his chance. His father was an engineer and his mother a saleswoman and he resented the lack of opportunities young people now had in East Germany. He had applied to visit his sister on more than one occasion but his requests had been turned down with no reason given. So instead, he began planning an escape and was joined by his co-worker Helmut Kulbeik. Kulbeik recalled that Fechter “had been planning to get to the west for some time. I too was disillusioned with my life and our government and the police and we were young and I was a bit headstrong and went along with it…” Ironically Kulbeik would make it to the west.

They scouted for sites where crossing might be easier. Only a year after being built the wall hadn’t reached the almost four-metre height it would top out at by the end of the decade. “We looked at a few places,” said Kulbeik. “But we had no definite plan.” Then they found an unused carpenter’s workshop in a building overlooking the death strip at Zimmerstrasse, not far from the border crossing point at the now-famous Checkpoint Charlie. One window had not been bricked up and the wall opposite was only two metres high, topped off with barbed wire. Crucially, although the nearest East German watchtower could see the wall, it couldn’t see the window. “We decided this was the spot,” Kulbeik recalled.

The two youths sneaked out of work on the afternoon of 17 August, intending to wait until dusk. But once hidden in the workshop they heard voices and panicked. Fechter now had moments left to live. They jumped from the window and set out across the death strip, Fechter leading, Kulbeik behind. The wall was 10 metres away. They were spotted, no warning was issued, and the guards began to shoot. Astonishingly Kulbeik made it to the top of the wall and turned round to pull Fechter up. But the latter was terrified, and was attempting to hide behind one of the supports propping up the wall. Kulbeik dropped to the western side and freedom. He heard the bullet strike Fechter in the pelvis and heard him screaming “Helft mir doch, helft mir doch!” (“Help me, why aren’t you helping me?”). They were words that would never leave him.

Margit Hosseini was a student celebrating her birthday nearby on the western side of the wall. She told the-berlin-wall.com website that it “was traumatic, hearing him scream for help, and pleading as his life was seeping out of his body. It was terrible.” Hundreds of onlookers gathered, including journalists and photographers, on the western side watching Fechter lying in the death strip, still alive but mortally wounded.

The border guards on the east left him alone, either shocked at what had transpired or as a message to any other would-be defectors. Later, the head of the East German guards said his men were unwilling to intervene because they feared being shot at from the west. American soldiers and West German police were urged by members of the public to help Fechter. He was thrown bandages (he couldn’t reach them) but nobody would go to his aid, some fearing for their lives but also aware that they would be violating one of the most politicised borders in the world.

This would later lead to accusations of cowardice. Why hadn’t the West Germans and Americans gone to help him, under the truce of a white flag or under the protection of the red cross, many asked? Stories differ, American soldiers on the spot insist they were told not to intervene by their superiors, and members of the public were stopped from going to his aid by the police.

Although at the eventual investigation into his death after the fall of the wall the forensic pathologist said that had help reached Fechter, he would have died anyway, and that would not have deterred furious West Berliners from rioting that evening. Shouting “murderers” they attacked American soldiers and West German police who they believed were complicit in Fechter’s death, as well as throwing rocks and bottles at East German guards. Mayor Brandt had to issue calls for calm as chants of “Yankees go home” and “Yankee cowards” echoed around the city.

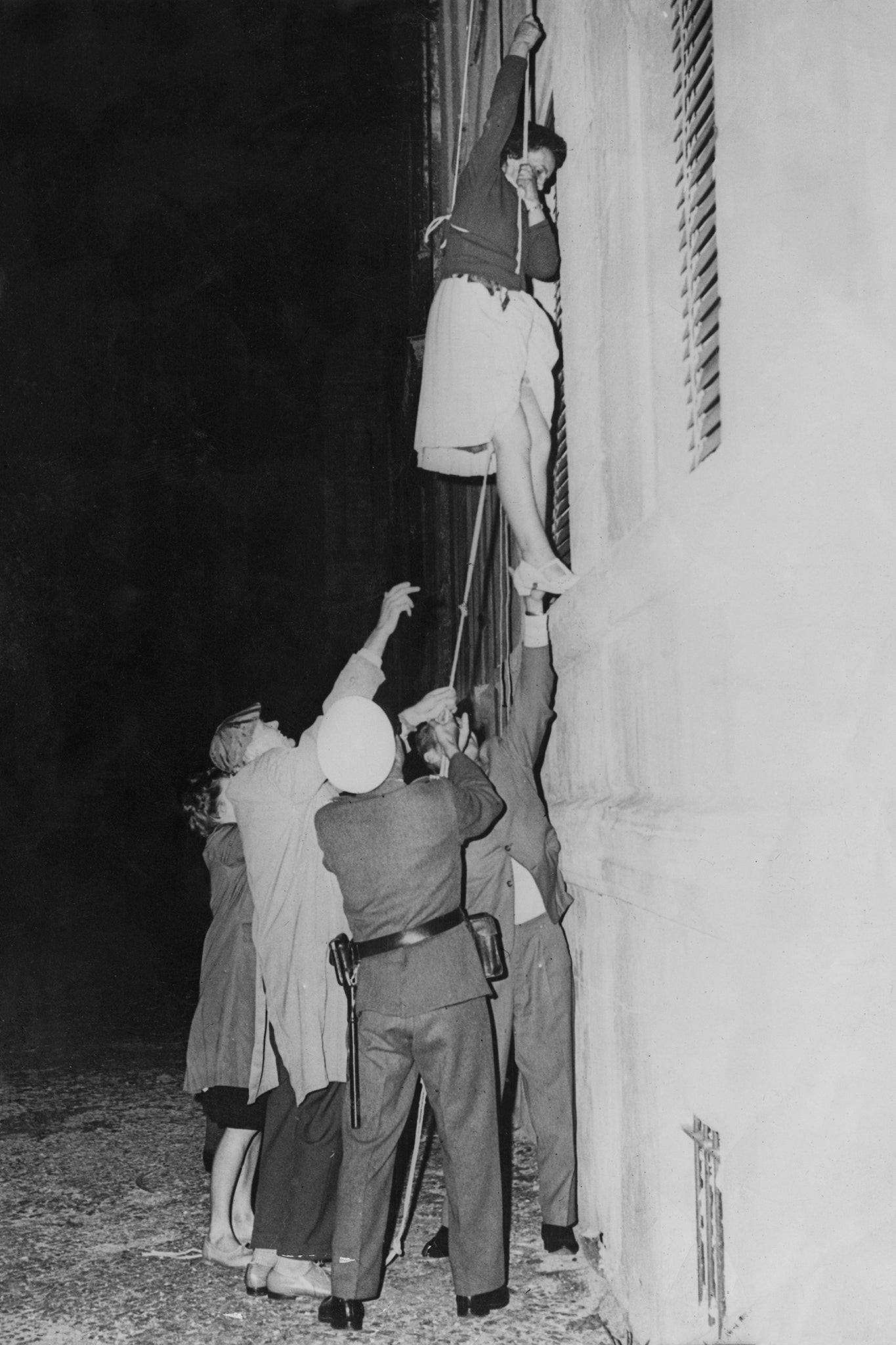

About an hour after he was shot Peter Fechter died. “He was the only son, the darling of his family,” his sister Gisela Geue was later to say. Eventually his body was carried away by the East German guards. The world’s media was looking on. Wolfgang Bera, a German news photographer, climbed the western side of the wall and took photographs through the wire of Fechter lying at the foot of the wall, while cameraman Herbert Ernst stood on a viewing platform and began to film. He and Bera took shots of the guards dragging Fechter away, like a “wet sack” according to Ernst. Their pictures would be shown to the world and remain some of the most traumatic of the Cold War era.

German newspaper Das Bild used Bera’s photographs beneath the headline “Guards let 18-year-old bleed to death – as Americans watch”. Morgenpost used Fechter’s dying pleas as its headline. Every news outlet in the west carried the story and its aftermath for weeks. “Wall of Shame” proclaimed Time magazine. Ten days after his death Fechter was buried. The funeral was supposed to be secret but 300 turned up. The Stasi, or East German secret police, were present, checking to see who came. A government official spoke at the ceremony saying Fechter had been “foolish”. “The Stasi even took away the flowers,” said Geue. “My parents never recovered,” she added, describing their later years as “miserable mental cases”.

After the wall came down Ruth Fechter, Peter’s younger sister, brought charges against the guards who had killed her brother. One had already died but the other two, Rolf Friedrich and Erich Schreiber, admitted manslaughter. It was impossible to prove whose bullet had killed Fechter but he was hit only once despite many rounds being fired, which suggests the guards had been reluctant to kill him. This mitigated in their favour especially when a letter was discovered, written in 1962, from Schreiber to his girlfriend in which he said he was scarred by what had happened and believed he might be a “murderer”. The letter was intercepted by the Stasi and never read by his girlfriend.

Both guards showed remorse for what had happened. Ruth Fechter said that after years of “objectivity” and “powerlessness” for her family the trial had given her a chance to evaluate the circumstances surrounding her brother’s death after years of hostility from the East German state. “World history fatally intersected with the fate of a single individual,” she concluded.

Fechter’s death spawned many TV documentaries, an Institute of Contemporary Arts live performance directed by Mark Gubb, an orchestral work by Aulis Sallinen, a play by Jordan Tannahill, a song by Spanish artist Nino Bravo and a memorial to him built at the spot where he died on Zimmerstrasse. The memorial replaced a wooden cross that initially stood on the western side of the wall next to where he was shot. “He just wanted freedom,” reads its inscription.

There can never be any solace over such slaughter however much we may wish it upon dreadful circumstances, and it is trite to believe or hope otherwise. Insisting that good came of tragedy is a device merely used to comfort those saying it. So the fact that Peter Fechter is still widely remembered today is of no particular benefit to his family nor the many more people who would die at the wall.

But while there can be no consolation for his family nor those who witnessed his death, Peter Fechter went on to symbolise the absolute failure and utter futility of an ideology that had lost any moral compass it might have claimed to possess. The moment the bullet shattered his pelvis was the moment the whole project was doomed to fail. His death created a simmering fury that was only becalmed when on an astonishing night in November 1989 Berliners tore down the despised wall with their hands. At that moment the epitaph on Peter Fechter’s gravestone took on new meaning. “Unforgotten by all,” it reads. “He was shot only because he wanted to go from Germany to Germany, just like everybody can now,” said Geue. “But these inhuman people did not let him.”

Figures are uncertain but around 200 people would die at the Berlin Wall. The final death by shooting was Chris Gueffroy, a waiter who was about to be conscripted into the East German army. He was killed on 6 February 1989, a full 27 years after Fechter’s murder, and only nine months before the wall was torn down.

A final irony. Peter Fechter was a bricklayer and had been asked to help build the wall that would lead to his death. He helped build it but was perhaps more instrumental than anybody in its destruction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks