Handcuffed emotions: Is the police force doing enough to protect officers from trauma?

Ben Pearson was a traffic cop, attending several fatalities every week. But when his mother died and he returned to work too soon, his grief overwhelmed him. He talks to David Barnett about his new book, and how the force deals with mental health problems

Ben Pearson was parked in his patrol car on an icy February day when the call came through that an officer was needed to assist at a road traffic accident on his West Yorkshire patch. It was only half a mile away, but Pearson was fervently hoping that someone else would respond. No one did. He knew it was his duty, and he had to do it.

Pearson had just returned from compassionate leave after the death of his mother. The break from work wasn’t long enough for him to come to terms with his grief. He was on anti-depressants and struggling hugely, but privately. And what happened next was going to make things far worse than he could ever have imagined.

When Pearson arrived at the scene he discovered that the accident was fatal. And it involved a 44-ton, 18-wheeler truck. And a child.

Read More:

The members of the public who had gathered at the scene were relieved when Pearson, the first emergency services member to arrive on the scene, pulled up. Here was someone from authority, someone who was going to take control. Ben Pearson felt anything but in control. The scene he arrived at was horrific – and described in his book, Handcuffed Emotions – and it broke him. Instead of taking charge he started to cry.

“I could feel my legs on the floor, but I couldn’t feel any other part of my body,” he writes. “I looked up and there were about six people just staring at me. Lights and sirens were going. I thought they were saying ‘don’t panic, the cops are here. We’re okay now! But why is he crying?’ I remember they were shouting at me on the radio, but I couldn’t move my arms. The ambulance and air ambulance arrived. I heard the control room shouting, ‘Ben needs help here’. Someone put an arm around me and walked me to the car to sit down. The only thing I could think about was my daughter. It was like seeing her lying there.”

By the time he went on long-term sick leave in August 2019, eventually retiring from the West Yorkshire Police force in October last year, Pearson had served 19 years, most of them as a traffic officer. He appeared in the fly-on-the-wall Channel 5 documentary series, Police Interceptors, as the face of the county’s high-speed, high-octane, road-patrolling cops.

But through it all he was struggling to cope with the things he was seeing day in, day out, which eventually led to his breakdown and diagnoses with Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“I was seeing a therapist,” says Pearson, 44, who lives near Bradford with his wife Milly and their children, “and I was told that if I found it difficult to talk about things, I should try writing them down. I’ve struggled with dyslexia and I’m not really that good with computers, but once I started typing the floodgates just opened.”

Over the course of many months Pearson wrote down his thoughts, and then marshalled them into what became his first book. It is a powerful story of not only his life with the police in a hugely stressful role, but also a rallying call for more to be done to tackle mental health issues within the force.

After that particular flashpoint incident with the fatal accident, Pearson relates how the paramedics who were at the scene were sent home to recover from the things they had witnessed. He was told to go back to the station and write up his report, and finish his shift.

Although that accident was a pivotal moment, it had been building up for years. Pearson does not come across as someone easily triggered — it’s hard to see that he could be with the job he did.

I was coming home after picking dead children up off the floor, and then I would have to try to switch off and play with my daughter

“Writing everything down chronologically helped me to see where the breaking points were,” he says. “I can see things looking back where I should have changed the course of action or got help but you never really recognise them at the time, you just get on with the job, until you hit that point where you are actually broken.”

After his mother died, Pearson was taking anti-depressants, which made him, he says, somewhat numb to the job — he would lose fear, even when in a pursuit at 140 miles per hour. He had never been fond of heights but found he was almost reckless when his job took him to high places. But the pills were only masking the pain that he was trying to suppress while doing the job.

“Some weeks you would attend six or seven fatal accidents,” he says. “You would come into work and it would be one after the other, fatal, fatal, fatal… and you’ve not even allowed yourself to come to terms with attending the first one when you’ve already been to four or five more. They’re all mounting up in your head.”

One coping strategy for Pearson was to put each incident in a black box and file it on a shelf in his head. That worked for a while but, he says, “the black boxes keep mounting up and you’ve no more shelf space in your head”.

While he was keeping it together at work, albeit bolstered by the tablets, the dark hours of the night were a completely different – and terrifying – matter.

“I was coming home after picking up dead children off the floor, and then I would have to try to switch off and play with my daughter,” he says. “And then I would lie there in bed and I would be surrounded by dead people.” He is almost apologetic about how this sounds, but it was very real to him. “I could smell their presence, taste it,” he says. “They really were there to me. I would leap out of bed and think there was someone in the room and go to tackle them, but when the light went on there was no one there.”

Pearson’s big issue – and that which led him to publishing his story – was that there was never any proper support during those years. The culture of the police, he says, means it was difficult to admit to having mental health problems. Colleagues didn’t know how to handle it, officers were afraid to show signs of what might be seen as weakness. The general advice was for anyone who was having a wobble to “man up”.

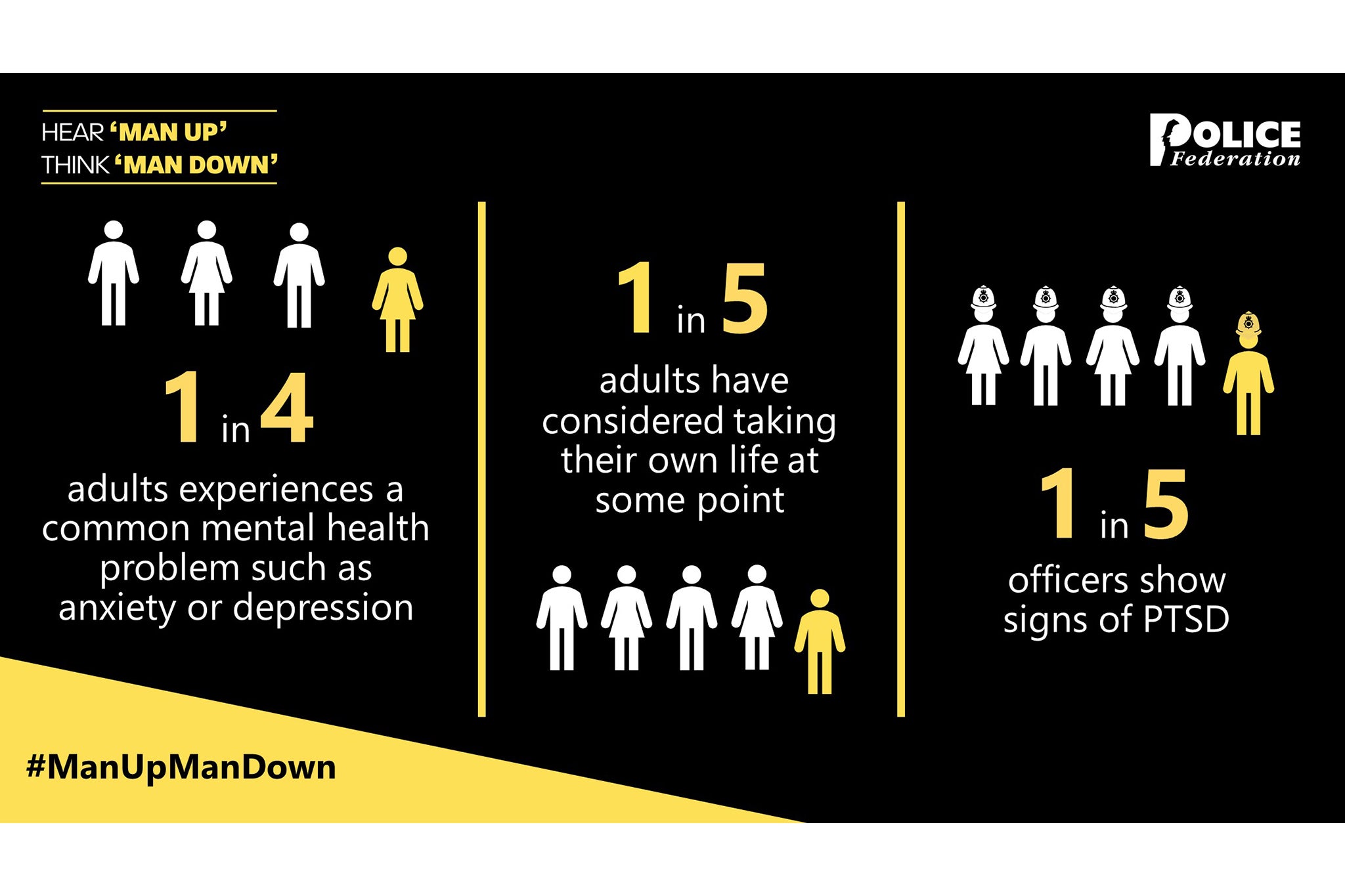

According to the Police Federation, that's a widespread issue in the force. Gemma Fox, the Roads Police Lead with the federation, says: “Sharing the load can make the world of difference to you and your colleagues – in every respect but especially when it come to dealing with the difficult and often harrowing nature of policing. How do we even begin to process trauma? Especially for the mental health of our roads policing officers, for whom dealing with trauma can be an almost daily occurrence.”

The federation has a campaign called Hear “Man Up”, Think “Man Down” – essentially to encourage all officers to be more empathic and if they think someone is struggling, to offer support.

“The campaign is about recognising the signs when you or your colleagues are struggling,” says Fox. “It is about changing attitudes, reaching out early to avoid pain and stress spiralling out of control. If we can get one person to seek support before it all gets too much, then the campaign has been worth it.

“Trauma affects us all differently and no one is invincible. Talking is priceless and sharing the strains, stresses and anxieties of the job goes a long way in looking after each other’s mental health.”

Pearson knew he needed help when he was in his local Morrison’s supermarket. He imagined he was walking around the aisles with his black boxes full of horrific memories clutched under his arms – because there was no more room in his head. He says: “I got to the checkout and I was crying and everyone was looking at me because they didn’t have any black boxes.”

As well as doing his day job, Pearson had extra pressure through his appearances on the TV show. It’s something he enjoyed and relished, but he calls it “a double pretend. I didn’t really know I was poorly at the time,” he says. “I loved every minute of the show. But somehow I knew I was dying inside a bit and I had to not only put on a happy face for the job, but do it for the show as well.”

Organisations such as the police have been doing what they’ve been doing for a long time, and change with regard to mental health is slow

With his distinctive streak of white hair, Pearson became something of a local celebrity while Police Interceptors was airing, and would get stopped in the street for his autograph and to chat. And that had a positive effect. “It helped people see beyond the uniform,” he says. “I’d go for a drink in the pub and even criminals would be coming up to me shaking my hand. They weren’t just seeing a copper, they were seeing a human being.”

Pearson wishes he would have sought help earlier, and that the culture of the police had been more set up to recognise the signs of mental health issues, and to realise that they needed to be tackled and did not mean there was any weakness in the officer. Even in the 18 months since he went on sick leave, leading to his eventual retirement, he says things have got a lot better.

“I know they are far more on the ball with things,” he says. “There is much more of an open door policy at West Yorkshire and people are watchful for the signs.”

Assistant Chief Constable Angela Williams of West Yorkshire Police agrees that much has been done. “Policing is well recognised as a stressful job and the Chief Officer Team at West Yorkshire Police is acutely aware that pressures on officers and staff have increased during the past year because of the Coronavirus pandemic,” she says.

“We have always taken a very proactive approach with regards health and wellbeing here in West Yorkshire, and have implemented an ambitious Wellbeing programme, which includes support and assistance at a local and Force level. This approach focusses on all types of ‘health’ such as workplace health, lifestyle health, financial health, physical health and mental health.

“Throughout the past year, the full wellbeing programme has been in place and even more support has been offered virtually over the use of Skype video calls and other social platforms. We also have lots of support services for officers and staff, both online and in person.”

A Peer Support Network has been instituted, with officers trained to spot colleagues who might be suffering and to reach out to them first, rather than waiting for things to get to breaking point. A year ago the force started a Trauma Risk Management programme to help officers deal with the aftermath of attending highly traumatic incidents.

Pearson is glad about the changes and hopes that many of his former colleagues will seek the help that is available to avoid the problems that built up to such an extent they essentially ended his career early.

He is still in therapy once a week, and his illness has taken its toll. He cannot bear to watch violent movies, nor any TV shows featuring police work. He still gets a racing heart if he sees a police car flying past in the street. And he knows he has a long way to go.

“It’s about recognising there will still be bad days,” says Pearson. “I learned a new technique in therapy. Instead of carrying around all those black boxes, and there being too many to hold, I put them all in a rucksack. And every day I pick up this rucksack and decide whether it’s OK to put on my back and go out and do something. If it feels too heavy, then I accept that and just do nothing for the day. But that’s all part of the recovery.”

Read More:

His book has already sold in many countries and he’s had messages from not only police but other front-line workers – firefighter, military, paramedics – from across the world, telling him that they recognised in what he went through their own problems, and have started to seek help.

“Organisations such as the police have been doing what they’ve been doing for a long time, and change with regard to mental health is slow,” says Pearson. “But change is happening. It’s a learning curve, but we’re going the right way. It makes sense that officers are properly listened to and looked after, so they can get out there and do their job – protecting the public.”

‘Handcuffed Emotions’ by Ben Pearson. Independently published, £9.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks