Homage to Catalonia: Exploring Barcelona’s cycling revolution

The Spanish city is putting itself at the forefront of urban mobility when it comes to cycling and e-bikes, so what can we learn from it? Asks Sean Russell

The children attached purple balloons to their bags and to their bicycles – in recognition of international women’s day – and music blared out before they set off for school. This might seem normal, but this wasn’t just a few children, it was 50, most of whom were with their parents – they also had a police car to follow them. This was Barcelona’s BiciBus, and they were taking over the roads during Friday morning rush hour.

We left the Sant Antoni district at 8.30am and joined a busy road. The traffic had a green light to go but the cars did not move, instead adult volunteers on bikes in high-vis vests lined the junction, stopping traffic while the children swarmed on to the wide road. The police car followed on behind quietly, and we followed the music all the way to school.

It is a simple idea really. If you have nearly a hundred people riding, there’s not much a car can do but sit behind, therefore creating a totally safe environment in which children can cycle to school. Should it really take this minor form of protest to create safe roads for children? Perhaps not, but right now it’s necessary, and it might not be needed just in Barcelona but in cities across the world if real safe roads are to become normal.

There is an aim to the BiciBus. Yes, it is a party and there is music and a carnival atmosphere, but underlying the whole thing is a message. Put simply by Mireia Boix, a mother and volunteer with the BiciBus, if the city doesn’t provide the people with safe bike lanes, then we’re going to take over the roads every Friday morning during the school run until they do. Does it cause much disruption? Not really, although the group definitely have their “haters”, the whole thing lasts 20 minutes and who can get mad at small children cycling to school? But nevertheless, the police provide a car that follows behind, just in case. It also shows that the authorities are paying attention to the group aware of what they stand for.

“The way we see it, if the roads aren’t safe for children, then they’re not safe for anyone,” Boix told me.

Barcelona, like many cities across Europe, is going through something of a cycling revolution. Cleaner, healthier and more environmentally friendly modes of transport are key not just for our planet’s future but also the health of a city’s inhabitants and children. Air pollution causes 9,400 premature deaths a year in London at a cost of between £1.4bn and £3.7bn a year to the health service. Meanwhile the average CO2 emissions per car in the UK is 228.2 grams per mile, according to the Department of Transport and 25,341 reported collisions in London in 2019 resulting in 125 deaths.

With 68 per cent of the world’s population due to live in cities by 2050 there are currently only a few ways to alleviate these problems. One is, of course, electric cars. While this may deal with pollution and CO2 it does not deal with congestion, and if you have a million cars, you need a million parking spots at the point of departure and arrival. That’s a lot of space taken away from people. And so that’s where cycling comes in: a machine invented in 1817 may well be the future of our cities.

Didac Sabate is the co-founder and force behind Panot, a Barcelona based e-bike company, which has produced a bicycle expressly for the purpose of getting around a city. He sees the e-bike and cycling in Barcelona in general, as the second urban revolution of the city. The first, he says, was the Panot floor tiles, which cover much of the pavement. The city used to be mud streets, and it was very slippery, but with the creating of the flower tiles people stopped slipping. It was about urban mobility, and so is the e-bike – hence the borrowing of the iconic name “Panot”.

What we rode

PANOT e-bike

Frame

Material: aluminum

Sizes: one size (max 125 kg).

Transmission

Shimano Nexus Mechanical Internal Geared Rear Hub 5 speed

Shimano Nexus 5 speed shifter V (grip)

Motor: Shimano STEPS E5000 40Nm

Battery: Shimano

Display: Shimano STEPS E5000

Wheels

Rims: aluminum 20″

Components

Brakes: Tektro hydraulic discs

Handlebar: folding

Pedals: folding (included)

Other accessories: lights, fenders and rear rack.

His Panot bikes have small wheels, fat tyres, and a Shimano-powered pedal assist electric motor which you barely feel working away under youThe bike has a range of 75km. It’s comfortable, easy to store in small homes and it’s fun to ride. Above everything it reliable, that’s why they chose Shimano’s STEPS system and battery, that’s also why instead of a chain it has a carbon belt like a motorbike. Sabate wants it to be the ultimate city bike for the future of urban transport.

What the e-bike does that a regular bike does not is open up cycling to almost everyone, regardless of fitness levels or physical ability, which means people that might not have cycled before now can. Barcelona is a hilly city, but with a Panot bicycle you’ll feel like you have the fitness of Tour de France winner Geraint Thomas. Sabate took me out on a Panot and it was like stepping on to a bicycle for the first time again. “The key,” says Sabate, “is if the rider smiles when they first step on.”

This is a trend where Barcelona is ahead of the likes of London. Whereas in London and other UK cities you can get a Santander bicycle, there is less provision for a rented e-bike. Barcelona on the other hand gives a choice between regular pedal-powered rental bikes known as Bicing and also an e-bike version. The percentage of bike rentals has gone up, but most notably those choosing to rent e-bikes over the pedal-powered sister is soaring, leading the city to invest in more e-bikes for rental. It can only be a good thing for the city. More demand for bikes, more people cycling, means more demand for better infrastructure. And the feeling of change is in the air. “It’s crazy how much the city has changed recently,” said Sabate. “We want to be the main city for mobility.”

This is echoed by Manuel Valdes, the city manager of infrastructure and mobility for City Hall. We sat down near the arch of triumph to talk about urban mobility and his eyes lit up as we began to talk about cycling; he showed me pictures of himself cycling in the snow of Scandinavia and in the hills and mountains of Italy. He says there is a three-pronged approach to changing the city: walking, cycling and public transport. There will always be cars he says, but there needs to be less. More space needs to be taken back from cars.

One of the issues with the cycle lanes in the city, certainly of some of the older sections, is that they are two-way. Imagine your average one-way cycle lane in London, then split it in two. There is barely enough space for regular bicycles to pass each other, let alone a tricycle, cargo bike or handbike. Several times while riding around the city with Sabate I winced as oncoming riders fired by at speed just inches away from me.

“People ask us why we don’t we use bike lanes,” says Genis Dominguez, another parent and the founder of BiciBus. “We say they’re not safe for kids, they’re just too narrow.” Another parent and BiciBus volunteer, Rosa Surinach, tells me about cycling with her own child through the city, and about how her son wants to ride side-by-side with her, but is terrified of oncoming traffic. These lanes do not encourage new cyclists.

So why is it two-way? To provide more space for cars. Something that Manual says he is changing. Soon, bikes will be taking back space on the roads and the two-way lanes will be replaced with something similar to what we have in London. But that is not to say that London is by any means better or safer to cycle around. The cycling infrastructure we have in London and other cities is often good where it exists, but it there is just not enough of it. Over three days in Barcelona I rode on roads perhaps twice while covering approximately 75km. The rest was on dedicated lanes. The lanes in Barcelona are disparate and sometimes confusing, but they exist and mostly feel safe.

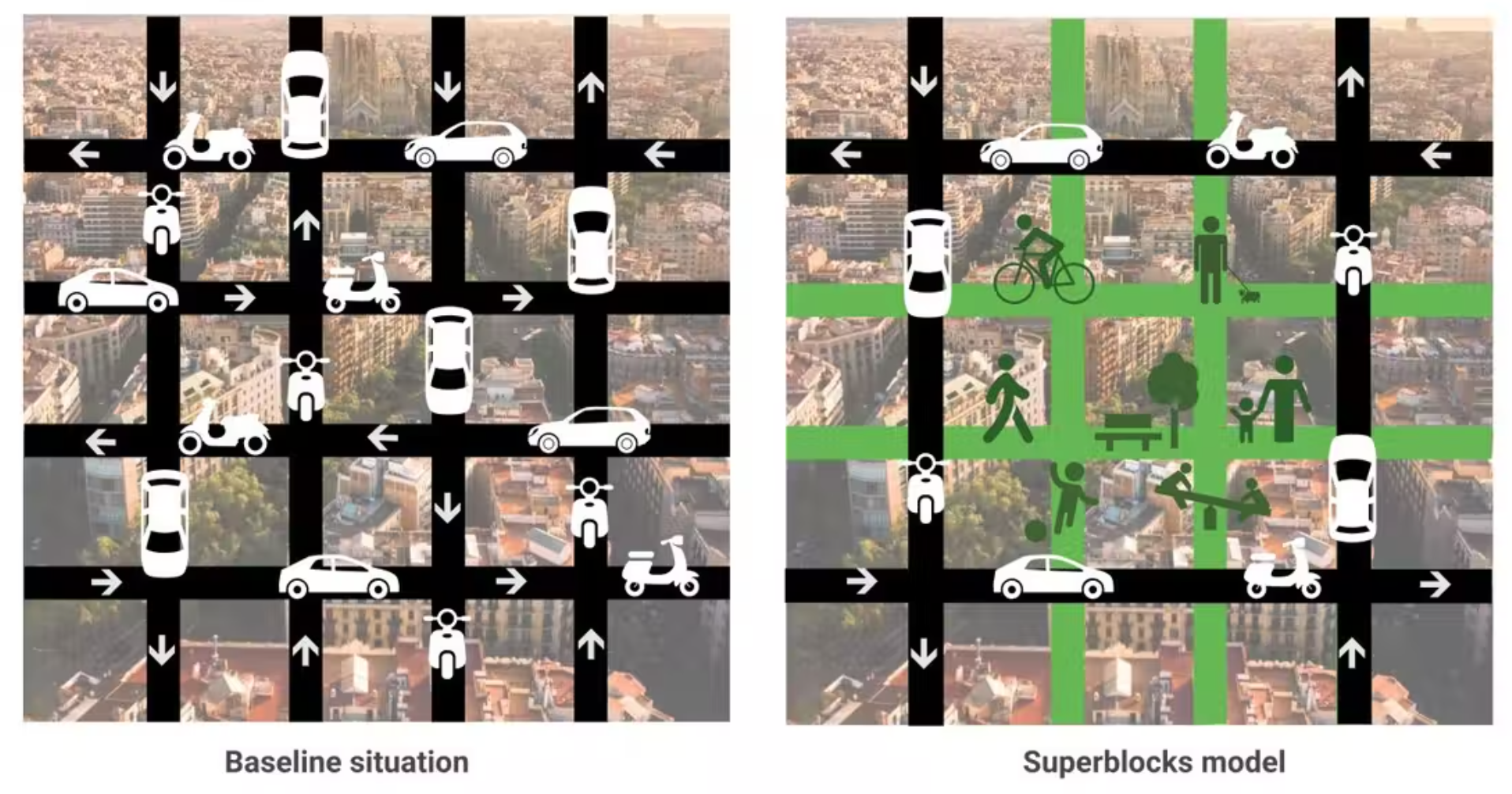

Why is Barcelona setting itself up to be one of the leading urban mobility cities in Europe? Well, why not? It is a small city with a lot of people. If there can be a revolution here, there can be a revolution anywhere. Taking streets back from traffic isn’t particularly new here. Sabate took me to see one of several “superblocks”, a glimpse of what a low-traffic could look like in the future.

Barcelona has a unique set up. Outside of the higgledy-piggledy old town, the city is made up of uniform square-like blocks of buildings. The superblock idea is to take nine of the blocks and turn them into low traffic neighbourhoods, allowing more space for people to meet, walk, cycle, and play.

As we arrived at the first block in the Sant Antoni area, I was struck by the quiet. I could hear voices, I could even hear birds, but I couldn’t hear cars. It was a little oasis in the city. Streets where people could meet safely, where children could cycle and walk around without fear. In many ways it is how one imagines the past before cars, when kids could play in the streets. It was a vision of the city of the future, not just Barcelona but the world.

In the first superblock we visited there were chessboards and benches, flower planters, and tables. Along with the bars and coffee shops dotted round, it was a social centre where people could hang out and meet away from the busy roads. Another superblock we visited made use of the extra space by installing climbing frames. All is done in consultation with residents, giving each block a unique feeling and somehow representative of that individual neighbourhood.

There have been push backs, of course: in L’Eixample for example, where shop owners worry that their businesses and customer bases will be affected. While the council has argued that only 5 per cent of customers access L’Eixample’s businesses by car, there is still strong opposition there. “The change is hard for them,” says Sabate of the shopkeepers, “but this is the future and so far it seems that the businesses are doing even better where the superblocks are.”

London’s low traffic neighbourhoods have been a start, but so much more needs to be done. There is always a feeling that any changes London makes are only temporary. We only have to look back at the pandemic to see that. Where roads were closed to traffic, and restaurants and pubs took over the streets, we saw what could be: a bustling space full of people chatting and being with each other, but come the end of the toughest restrictions came the end of these low-traffic areas, and the vision of the future came tumbling down.

The same can be said of cycling lanes. As people sought to travel by bike during the pandemic more lanes were put in and for many of us it seemed like a corner had been turned, that the only way was forward. Instead, many of those lanes were removed at the first opportunity. So would that happen to Barcelona’s superblocks? “No,” says Valdes. “No,” says Sabate. “No,” says Surinach. The superblocks are part of a plan for the future. There are currently six superblocks with the intention of building many more.

“Cycling makes me happy,” says Laura “Lola” Vargas. “It’s the way I choose to move around with freedom. For me as a woman in Latin America it is a strong choice to make, to move around by bike.”

Vargas’s Brompton is somewhat unique. Bought in Bogota, where she is from, it is now with her in Barcelona, half-way across the world. It is blue and pink and if it were lost, stolen, or broken then Vargas would be devastated. Vargas is part of Bicicleta Club de Catalunya, a non-profit organisation dedicated to improving cycling across the city and getting as many people cycling as possible. It carries out research to help decisions across the city but they also work at the grass-roots level helping to teach people how to cycle.

That is Vargas’s favourite part, getting out every weekend to teach people of all ages how to use this tool. She says that more women cycle in Barcelona than Bogota, but more can be done. She believes that by creating better infrastructure more groups of people will feel safe. If the signs are easy to read it’s hard to get lost, if the lanes are wider and separated from traffic then there are less terrifying moments. She also thinks which bikes people ride is important.

“I did a survey and found that women were just as likely as men to ride a foldable bike, like a Brompton, while road bikes were ridden much more by men.” Perhaps there’s something in that, is the bike itself more accessible to groups less traditionally involved in cycling? Do certain bikes intimidate while others are more welcoming? There’s another part to it as well, Vargas says. There needs to be more communication between groups. There needs to be cooperation to change cities in a way that benefits cleaner, safer modes of transport but which doesn’t ignore the issues of car users.

“The most important thing is the confidence of people,” says Valdes. “If we don't have public confidence, all these policies are impossible.”

Valdes says the aim is for 81 per cent of all trips to be walking, cycling and public transport, with the number of private vehicle journeys dropping from 26 per cent to 18. Meanwhile, currently 2.2 per cent of all trips are made by bicycle and this number they want to increase to 5. A key part of reaching that 5 per cent is, Valdes believes, increasing and improving cycle lanes and infrastructure. Currently Barcelona has about 250km of bike lanes (it is also legal to ride on pavements more than 4m wide), and they are working on another 32km while transforming 11km – taking them out of the pavements and taking back the space of cars. Part of this is replacing the two-way bike lanes in the oldest parts of the system.

Along with the roads, Barcelona is increasing the number of streetlights and signposts along with the number of bike storage points across the city. “One line of four parked vehicles could be more than 22 bicycles,” he says.

The e-bike is an important part of the vision for the city; in 2022 Barcelona will have 4,000 electric bikes on their Bicing rental system and 3000 traditional mechanical bikes, because quite simply, the use of electric bikes is higher. Sharing bikes, and other forms of transport, is key to reducing congestion in the city, says Valdes, and Barcelona’s council is aiming to push sharing initiatives, like Bicing, across the city.

It’s hard not to draw comparisons to London while riding around Barcelona. Both cities are doing many of the same things: London now has more than 100 low-traffic neighbourhoods and is always adding bike lanes and quiet routes to the more than 250km in place, although due to the size of London it doesn’t feel quite as connected as Barcelona. School streets are also a good step forward in London, of which there are now more than 500. But only 5.3 per cent of all trips in London are made on bicycle.

There is a feeling that communication is key. Valdes had just returned from a trip to London and is interested to see what London is doing. Meanwhile, there’s a lot we can learn from Barcelona. The main thing, perhaps, is to embrace e-bikes. By making e-bike rental affordable, to rival the Santander Cycles, is something that would open up cycling to those who may not have cycled before. Increasing fully segregated lanes to fit all types of bike from Brompton’s to cargos to handcycles would also help. We need to make cycling open and safe for everyone, if we don’t feel safe letting our kids ride their bikes then it’s not safe for anyone.

Sabate took us to one of the entrances to Barcelona near Finestrelles in the northwest of the city. We rode up and down twisting, new, fully segregated lanes cruising beneath the roar of the motorways crisscrossing above. It felt truly safe, and there were lots of different people out on their bikes, old and young alike. It felt like this was exactly what was needed, safe, but also fun. A place where everyone can cycle freely. “Barcelona’s time is now,” says Sabate. “It’s the second urban revolution.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments