For Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova the break-up of the union isn’t over

In 1991 Mary Dejevsky watched from her flat as the tanks entered Moscow. The attempted military coup lasted barely three days, but 30 years on the transformation of the former USSR still has some way to go

There is a certain fascination in watching events you have experienced and reported on become history, with everything neatly interpreted and the still open arguments set out on the printed page. The demise of the Soviet Union has to be a classic case. Over the past 30 years, dozens of explanations have been offered for the Soviet collapse, from the unsustainability of the planned economy, to the cost of trying to keep up with US arms spending, to the nationalist aspirations unleashed when censorship was relaxed, to the sheer inhumanity of Soviet communism.

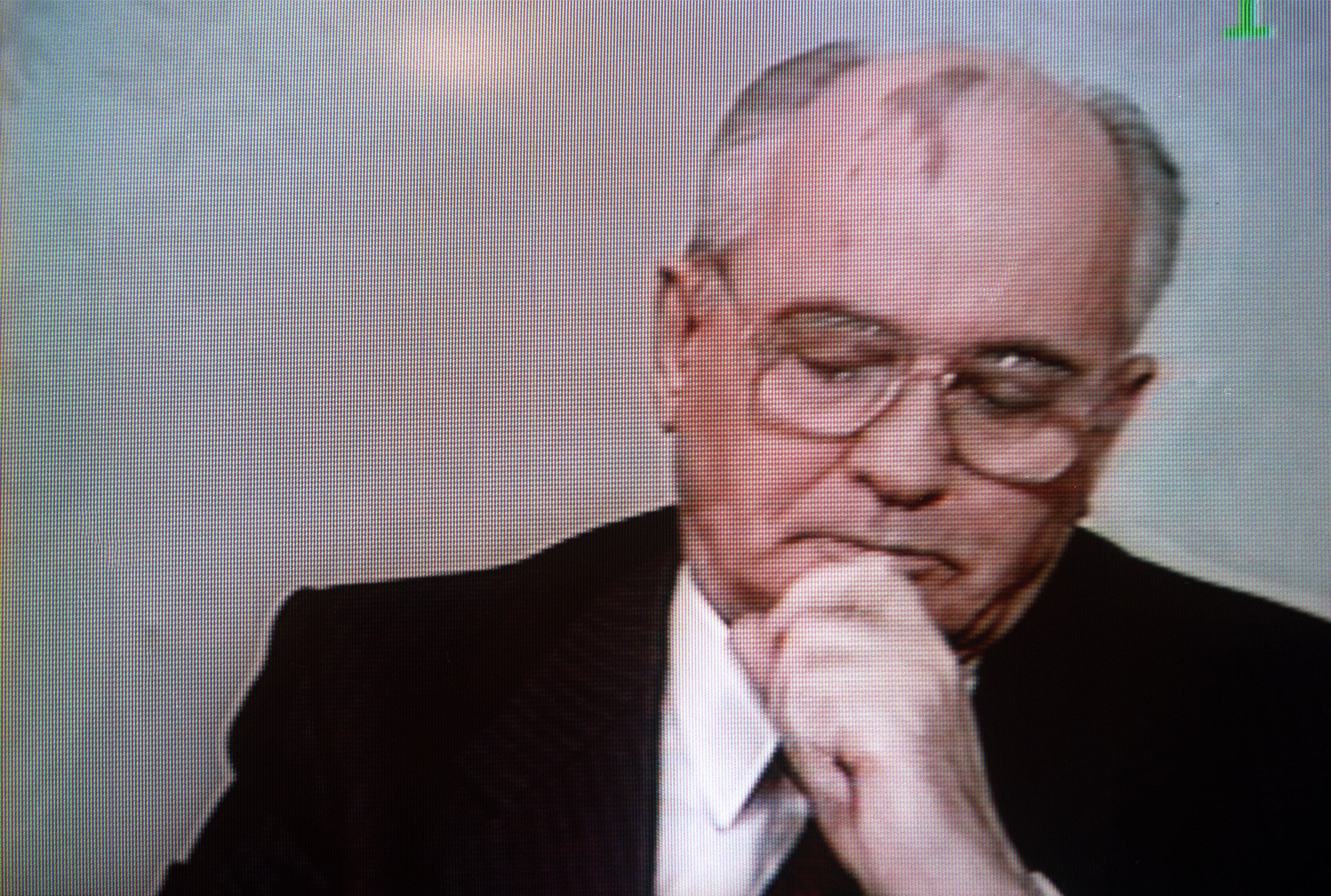

If there is still debate about why the Soviet Union collapsed, however, there is almost no debate about when. The red flag with the hammer and sickle that had flown over the Kremlin was lowered for the last time on the evening of 25 December 1991, shortly after President Mikhail Gorbachev had announced his resignation on TV. In its place was hoisted the Russian tricolour, and that, for the history books, is when the USSR reached its end.

Yet it is not quite as simple as that. You could argue, for instance, that the seeds of the Soviet demise were sown as soon as the USSR was formed by the Bolshevik government in 1922; that in its beginning was its end. Or you could say that it effectively ended with Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in the 1956 secret speech, which threw aside many of the principles that had governed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. It was then, by the way, that Crimea was transferred to the jurisdiction of Ukraine.

Then again you might contend that the Soviet Union was already little more than an empty shell when Gorbachev came to power in 1985. Or that, even if the union was still just about alive then, it had ceased to exist in any meaningful sense by 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, communism was rolled back across Europe, and the Baltic States, along with Georgia, started the quest to restore their independence.

Or maybe it was a year later that it all came to grief, when Gorbachev proposed a Union Treaty designed to hold the whole thing together by transforming it from a top-down federation to a bottom-up commonwealth. Or the following spring, when Boris Yeltsin – by virtue of being directly elected the first president of the Russian Federation – gained a popular mandate to steal a large part of Gorbachev’s power.

A case could be made for any of these events marking the real end of the Soviet Union. But my preference would rather fix on the hardline coup against Gorbachev that began 30 years ago on 19 August 1991. It lasted barely three days, but it changed everything, starting with the whole balance of power. It left Yeltsin the undisputed leader of Russia; it left the still nominally ruling Soviet Communist Party outlawed, and it left Gorbachev president in name only of a union that was disintegrating by the day.

It precipitated the renewed independence of the Baltic States – which was at once recognised by the western countries that had never formally accepted the Baltics’ enforced Second World War incorporation into the USSR. Within days, almost every other constituent republic of the Soviet Union had followed suit, with declarations of their own sovereignty or independence; within weeks many had held votes to secede.

Through the autumn, these were more declarations of intent than acts of actual secession, as they were not rewarded with the international recognition that the Baltic States’ now enjoy. Indeed, the US Administration, for one, made no secret of the fact that it regarded the Baltic States as an exception, and still hoped that the union in some form could be salvaged. The alternative – the disintegration of the second nuclear superpower – was just too momentous an eventuality to contemplate.

Those misgivings were shared by the largest of the Central Asian states, Kazakhstan, which became the last of the Soviet republics to adopt an independence declaration, just days before Gorbachev resigned. But the move that really proved decisive was the referendum at the beginning of December in Ukraine that produced an overwhelming vote for independence.

Just a week later, on 8 December, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarussia met at a hunting lodge at Belavezhskaya pushcha in Belarussia, renounced the 1922 treaty that had established the Soviet Union and set up what they called the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in its place. These were the three countries that had initially formed the Soviet Union, which gave them the judicial authority to disband it.

Their idea for the future – a confederation of independent states – was loosely modelled on the European Community, which, by a quirk of fate, became the more political European Union courtesy of the Maastricht Treaty that was finalised by heads of government in the two days (9–10 December) immediately after the Belavezhskaya accord sent the Soviet Union hurtling in the opposite direction. Nor did the CIS ever come into being, despite the ambitions of newly independent Belarus, with its capital, Minsk, to become the Brussels of the new grouping. The centrifugal forces tearing the Soviet Union apart were simply too great.

But all this is to jump ahead. It is not only because the August 19 coup effectively destroyed the centre of Soviet power beyond recall, accelerating separatist trends unleashed by Gorbachev’s reforms, that, to my mind, it constitutes the real end of the Soviet Union. It is also because of what the course of the coup demonstrated about changes in Russia – by far the biggest and most dominant constituent part of the USSR.

The coup was carried out by a self-appointed Emergency Committee of communist hardliners, who had travelled down to the Crimean villa where the Gorbachevs were enjoying their summer break, forced him to resign on the spurious grounds of “ill–health”, and seized power for themselves on the timehonoured pretext of “saving the country”.

![Leaders of the three most powerful ex-Soviet republics – Ukraine, Belarus and Russia – sign a communique agreeing that ‘the Soviet Union as a geopolitical reality [and] a subject of international law has ceased to exist’](https://static.the-independent.com/2021/08/10/14/GettyImages-51959225.jpg)

But the coup failed – but why it failed is crucial. Its leaders could not exercise the power they had tried to seize, and by the 21st it was all over when Yeltsin sent a delegation to free Gorbachev and bring him and his wife, Raisa, back to Moscow. The Moscow that Gorbachev had left for his holiday and the Moscow that greeted his return, however, were different places.

To be sure, the coup seemed something of an amateur affair from the start. The organisers had managed to take control of the media – there was only the state-controlled media in those days and they behaved in the standard way for an emergency, bringing all the channels together and broadcasting the same thing: in this case an old recording of Swan Lake (in black and white), with the statement by the Emergency Committee scrolled across it. But they had not secured the streets, even of central Moscow.

From around 8am, I could see from the window of my flat overlooking the main thoroughfare that columns of military vehicles, including armoured personnel carriers, had entered the city. But the rush hour, such as it was, proceeded as on a normal day in August. Buses, trolley buses and private cars threaded around the military convoy, with very little disruption.

From around 8am, I could see from the window of my flat overlooking the main thoroughfare that columns of military vehicles, including armoured personnel carriers, had entered the city

My driver – foreign correspondents had drivers in those days – arrived for work as usual and we took the car around the city just to see what was happening. I took all possible documentation on the grounds that there would be controls, and fully expected to be back within the hour. In the event, we cruised around Moscow encountering almost no blocked roads. In some ways, it seemed there were less blockages than usual. The first we encountered was very close to the Kremlin.

We then made our way to the White House, the building then used by the Russian Federation’s parliament, as opposed to the Soviet Parliament that met in the Kremlin. There was a row of tanks at the foot of the steps on the river side of the building, but no efforts had been made to keep people away and a crowd had gathered. As journalistic luck had it, we arrived in time to see the Russian president, Boris Yeltsin, emerge from the entrance at the top of the steps, and make his way down, surrounded by an entourage trying to persuade him not to.

This is when he clambered up on to the closest tank – again, with no security, either of his own or from any military personnel trying to stop him – and made the speech of defiance that consolidated his grip on power. Those images, subsequently beamed around the world, but not around the Soviet Union, became the defining images of the coup, or rather the resistance to it. But that was not evident at the time. And before social media, or even free broadcasting stations, there were few ways of getting the news out, other than by (substandard) landline telephone or by word of mouth.

By early evening, hearsay and the end of the working day were having their effect, and a much larger crowd had started to gather around the White House, now seen as a fortress of the resistance. And there were a few more signs already that the coup might not be going as planned: some of the people who had seen Yeltsin on the tank brought flowers and placed them in the turrets of tanks positioned on the parapet of the White House – without any objection from the vulnerably young-looking soldiers manning them.

Late afternoon had seen the embarrassing press conference at the media centre, to which, as I recall, we had been summoned by the telex service of the official news agency, Tass – the usual way of assembling reporters. This is where the Emergency Committee tried to present its case, where the shaking hands of its chairman, Gennady Yanayev, became the testimony to their nerves – or their drunkenness – and where a young Soviet woman reporter, Tatyana Malkina, made her name by daring to ask, straight out, whether they understood that what they had done was to carry out a coup d’etat.

For the coup plotters, the press conference – which was broadcast live – was a big mistake, not least because they were naive enough to take spontaneous questions from the floor, and because this question, from a Soviet, rather than a foreign, reporter, was so bold and the answers were so inadequate.

If the success of the coup was now in doubt, however, the attempt to seize power was by no means over. And what happened next was as remarkable as Yeltsin’s speech on the tank and Malkina’s question at the press conference. Hundreds of Muscovites massed outside the White House, in the pouring rain and the gathering darkness, to defend Yeltsin and oppose the coup. Young men trouped into the basement of the building to be sworn as volunteer fighters and have holy water splashed over them by Orthodox priests before taking up positions outside the building, where they fully expected they might have to die.

Tanks did begin to move late in the evening, circling around and around the Moscow inner ring road, but they went nowhere and there was only one clash, when three people were killed trying to stop one. Some state television staff had defied the state of emergency to gather and broadcast dramatic footage from the White House.

It also emerged that Soviet journalists’ film of Yeltsin’s tank speech had been rushed to the airport and entrusted to a passenger bound for the Russian Far East, where it was broadcast first thing the next morning. Whoever thought to do this understood that effective censorship might not extend to Russia’s Pacific and that the time difference meant that it could start the day’s bulletins – which it did. But it was another day and a half before the plotters gave up and Yeltsin was fully in charge.

For me, these three days marked the end of the Soviet Union. But it is also strange to read now the unanimous retrospective judgements of historians that the coup was always doomed to fail. It was not. For 36 hours the fate of this whole huge country hung in the balance. The reasons why it failed, however, are the same reasons why the Soviet Union collapsed.

It was not just that the coup plotters had not been efficient or ruthless enough to force their will. It was that Russians had a leader in Boris Yeltsin, who publicly rejected the coup. It was that enough of the troops did so, too, when they turned their tank turrets away from the White House and their officers ordered them to trundle around the ring road – but nothing more. It was also that Muscovites of all generations and backgrounds were brave enough to come out on to the streets to defend their president and parliament, and that a new generation of professionals – including a quorum of journalists – chose to rebel. It was this comprehensive change of mindset that brought the Soviet Union to an end.

This is why I reject the widespread thesis that the Soviet Union simply evolved into today’s Russia without the great break that characterised the overthrow of communism across Europe, as country after country threw off the Soviet yoke. Russia had its moment of casting off communism, too. And it has not returned.

If Ukraine and Moldova are still tied, if only in conflict, to Russia then the separation of Belarus has only just begun

How complete was the transformation is another matter, which prompts a wider look across the whole of what is now known as the former Soviet space. And the reality is that, even 30 years after the Soviet collapse, traces of that legacy stubbornly remain – and not just in Russia.

Through the summer, autumn and winter of 1991–92, what was once a single, if increasingly dysfunctional, federation split into its 15 parts. Wars in Georgia, Chechnya, Moldova, between Armenia and Azerbaijan and in the Osh valley of Kyrgyzstan, among others, accompanied the break–up, as age–old disputes were rekindled. But mercifully, even miraculously, the conflagration many had forecast, a reprise of the 1917–22 Russian civil war, did not happen.

The largest loss of life in Russia, before the two costly wars in Chechnya, came in 1993, with the constitutional stand-off between Yeltsin and his parliament, which cost 147 lives and left more than 400 injured. As imperial break-ups go, however, the collapse of the Soviet Union and its immediate aftermath, may be accounted among the more benign.

That said, though, the process goes on; there were few or no clean breaks. The cleanest came arguably with the secession of the three Baltic States, which was recognised internationally immediately after the August 1991 coup and only weeks later by Moscow itself. In time, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were welcomed into Nato and the European Union, where they have joined Poland and the former Warsaw Pact states as a sometimes awkward presence.

A problematic past, imprinted by Soviet and Nazi German occupation, remains not fully resolved, but they suffered fewer years under Soviet domination than the other 12 Soviet republics, had enjoyed independence and a market economy within living memory, and were allowed marginally more cultural leeway than other parts of the Soviet Union – all of which made for an easier post-Cold War transition. The treatment of ethnic Russian minorities, especially in Latvia, however, remains a difficult reminder of the past, and resistance to diversity in general has placed them at odds with the EU mainstream on the vexed question of resettling refugees from outside Europe.

The five Central Asian republics had independence more or less thrust upon them, and are progressively becoming reabsorbed into their own neighbourhood and reclaiming their distinct histories. Russian generally remains the lingua franca, though young people are now learning English, and the economic orientation towards Moscow, while still evident, is weakening. That they have been left mostly to their own devices may be in part because both Russia and China have had other things to do.

Beijing’s recent moves to suppress Uyghur Muslims in its westernmost region of Xinjiang, however, could signal that its relative inattention towards former Soviet Central Asia will not last. And the same could be said of Moscow, if fighters from a disintegrating Afghanistan start to regroup across the border in Tajikistan. The Great Game could be on again.

One mitigating factor might be the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, created by China and Russia in 2003, which could provide a forum for preventing conflict in the region. Hitherto, though, it has failed to make much of a mark. On the other hand, it has also survived as a regional organisation without drawing flak from the west.

The same cannot be said of Russia’s other post-Soviet project: a Eurasian Economic Union modelled – so Russia would say – on the EU, but denounced by the US and the EU as an attempt to bind former Soviet states into Soviet-era economic and security ties. Of the three former Soviet republics in the Caucasus, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, only Armenia has joined.

Georgia was following its own national path even before the Soviet collapse, and has steered a jerky individual course, punctuated by a civil war, a so far unsuccessful bid to join Nato, and a Russian invasion, but always distinguished by a strong sense of its own unique identity. Armenia has remained closest to Russia economically, but – like Georgia – benefits from its ancient roots, its singular culture and support from a global diaspora, allowing it to keep some space from Moscow. Azerbaijan, for its part, has capitalised on its oil revenues and cosied up to Turkey. All three always had a life and a culture that was distinct from Soviet communism, so that there was plenty to fall back on when communism and the Soviet Union collapsed.

Which leaves Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova as the former republics that have found it hardest to establish themselves as independent states and have still not completed their breakaway. Moldova has moved gradually from the Russian orbit into that of Romania – leaving the separatist territory of Transnistria stranded as a frozen conflict in between.

Ukraine has to a large degree succeeded in functioning as an independent state, thanks again to a sense of identity, buttressed by a devoted diaspora. But it finds itself still tied to Russia by Soviet-era gas pipelines, what remains of trade and defence manufacturing – and, more painfully, by two Russian-speaking border regions that felt their identity endangered by a more assertively Ukrainian Kiev, sparking a military conflict and a proxy Ukraine-Russia war. Even the gas link may soon be redundant with the completion of the direct Russia-Germany link, Nordstream 2, but Ukraine’s increasingly westward orientation remains contested, within Ukraine and, of course, by Russia.

For a Briton, there is something of the Northern Ireland conundrum about it: a big power that, while formally recognising that the smaller country has left its tutelage, still cannot bring itself to accept, deep-down, that it is a country in its own right, able to stand on its own two feet. Until the big power accepts its loss of empire and the smaller country ceases to define itself by its opposition to its self-styled older brother, the separation will not be complete.

If Ukraine and Moldova are still tied, if only in conflict, to Russia, the separation of Belarus has only just begun. The paradox is that Belarus, though the closest to Russia in every way after the Soviet collapse, was among the first to adopt the trappings of independence, the national symbols, the national currency, road signs in its own language. Yet for the best part of 30 years it hardly moved to break economic ties, harboured hopes of its capital becoming the meeting point for the never-realised CIS, and relied on Russia for its security. There was even talk from time to time of a merger, a union, with Russia. And now, following a popular uprising last summer after what was widely seen as a rigged election, the new talk is of a “soft annexation” of Belarus by Russia.

It is hard, though, to see that happening. The trends are all in the opposite direction. Internationally, almost no country, once it has gained independence, gives it up. And the Soviet collapse is no different. Not one former Soviet republic has made the slightest move to reverse that status, nor – despite claims that Vladimir Putin wants nothing better than to restore the Soviet Union – has Russia made any move in that direction. Exerting influence, yes; restricting sovereignty, possibly. But reincorporating any of the former constituent republics into a new Union state? Not a hint.

What cannot be denied, however, is that the shadow of the Soviet Union still hangs to varying degrees over its former republics; that vestigial economic and transport links still testify to an empire that was ruled from Moscow, and that those Soviet republics closest to Russia in geography and culture have been the last to start, still less complete, their true departure.

The Soviet Union was consigned to history virtually overnight – between 19 and 21 August, 1991. Its founding treaty was renounced that December. Before the end of that month, its parliament had disbanded, its president had resigned and its flag had come down. It turns out, though, that this was the easy part. It was a mistake to expect that 15 fully functional independent states could emerge just like that. The break-up of the Soviet Union has taken 30 years and, for all the transformations along the way, there is still some way to go.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks