A most unlikely superhero: The lawyer of unwinnable cases

Andrew McCooey is one of the finest lawyers of his generation, and arguably its most humble. Now fighting Parkinson’s disease, Steve Boggan speaks to him about his incredible career

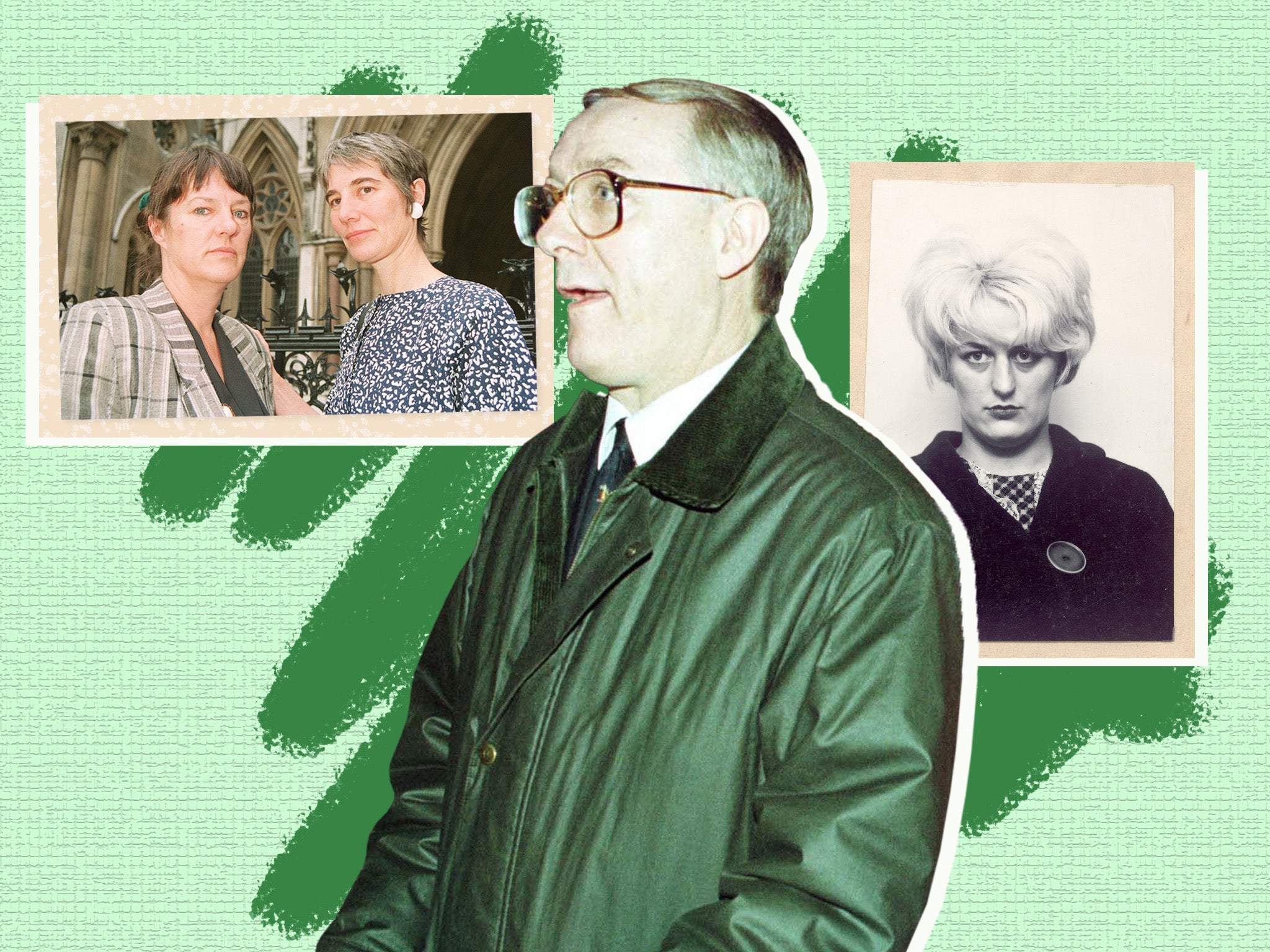

Andrew McCooey was the unlikeliest of superheroes, wearing clunky spectacles and off-the-peg suits that never came off to reveal a cape or mask or any noticeable superpowers. If he was taking on governments or judges, he would go about it quietly and without fuss, just as he would if you had reached out to him and asked him to save your life.

McCooey, now 73, is one of the finest lawyers of his generation, and arguably its most humble. He would take on unpopular causes, fight seemingly unwinnable cases and travel thousands of miles to save prisoners from the noose or the electric chair, often without taking a fee.

When no one else fancied the job, he took on Moors murderer Myra Hindley as a client, genuinely believing she was a changed person. “I do believe that everyone deserves justice and that they can be rehabilitated – no matter how horrendous the crime,” he said at the time, shrugging off death threats and disapproval.

I am sitting next to McCooey’s bed at his home in Sittingbourne, Kent, reading to him old clippings of past glories, of mammoth legal battles and of defeats and victories. Some of them generate smiles, others tears. We are taking stock of an incredible career because McCooey is in the final stages of Parkinson’s disease. His wife, Margaret, 75, who describes his life as being akin to “a Boy’s Own adventure”, says he has made peace with the fact that he is dying – his Catholic faith has seen to that – but he is frustrated that he can’t tell me this himself; his vocal cords are damaged and so speaking is almost impossible for him.

He squeezes my hand and whispers, almost inaudibly. I think he says: “We always tried to do the right thing, didn’t we?”

McCooey’s legal campaigning almost didn’t happen. He abandoned a putative law career in the 1960s and decided to study theology instead at Ambassador College, a religious university in St Albans, Hertfordshire.

“The plan was for us to go off and be missionaries but Andrew always asked too many awkward questions. I think they decided we weren’t what they were looking for,” smiles Margaret. “Instead, he went back to the law. He believed he could help more people that way. The staff at Ambassador told him he’d never make a good lawyer, but he proved them wrong.”

In 1989, his first high-profile case came along when he received a call from a distraught father whose 19-year-old daughter, a computer operator named Tara Terry, had been arrested in Miami and accused of deliberately starting a hotel fire in which two people died. If found guilty, she could face the death penalty, he said.

Though I believe Ian Brady is wicked beyond belief without hope of redemption (short of a miracle), I cannot feel that the same is necessarily true of Hindley once removed from his influence

McCooey flew to the US and found evidence that the blaze had been caused by an electrical fault. On the first day of Tara’s trial, the prosecution dropped the case. This led to the McCooeys and Tara’s family setting up Freedom Now, a foundation that would help people like Tara facing wrongful arrest, the threat of capital punishment or miscarriage of justice.

Funded by a handful of wealthy donors (and, often, McCooey himself), Freedom Now quickly chalked up a number of high-profile successes. As a solicitor, McCooey did not have right of audience at all courts, but where he needed a barrister, he often turned to the celebrated human rights lawyer Edward Fitzgerald QC, who also gave his time for free. “Even where Andrew did have right of audience, he would often call on Edward,” says Margaret. “He saw brilliance in Edward in those early years.”

Fitzgerald once said of his sidekick: “Andrew has the ability to cut through red tape, get to the heart of the matter and achieve results. It’s a case of small is beautiful. Most importantly, he’s a great diplomat – non-confrontational. He goes to a country, enters into a dialogue and works alongside the local lawyers.”

After saving Tara, Freedom Now fought for Lucy Christof, a British woman accused of heroin smuggling in Greece. McCooey proved she had been duped by drug traffickers and she was released. He then went on to successfully defend Layola Lynch, a woman facing a murder charge – and the gallows – in Belize. Lynch had had no money to fund her defence and would surely have lost were it not for Freedom Now.

In 2008, McCooey helped free Scottish-born former US Marine Kenny Ritchie, after finding new evidence to support Ritchie’s claims that he wasn’t responsible for a fire that killed a young girl in 1987. In a bizarre twist, Ritchie was jailed for 12 years in 2020 after posting videos on Facebook that appeared to threaten “the man who ruined my life”. Even though he did not name anybody, witnesses said they believed he meant Randall Basinger, the prosecutor who achieved his original conviction.

McCooey wasn’t always successful. His most high-profile “defeat” came at the end of a four-year battle against the extradition to the US of two gentle middle-aged Englishwomen, Sally Croft and Susan Hagan. They had been part of a religious community that followed the teachings of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh during the 1970s and 1980s, first in India and later in Portland, Oregon.

The women left the community in the late 1980s but six years later, to their astonishment, they were charged with conspiring to murder a federal prosecutor, Charles Turner, who had been investigating the group’s activities. The prosecutor was neither murdered, attacked nor harmed, and the only evidence against Croft and Hagan came in the form of uncorroborated statements by other members of the community offering up names in return for plea bargains.

The fight ended at the High Court in July 1994 with the women being told to surrender themselves to American law enforcement officers at Heathrow airport within a few hours. McCooey and I, and a stunned media circus, accompanied them on the long Piccadilly line Tube ride to Heathrow. Andrew tried to comfort them as they cried with members of their family. The women were released on bail in the US for a year and finally served just two years for conspiracy to murder, a term so short as to demonstrate the spurious nature of the charge.

Croft told me: “Andrew is such a really, really good-hearted man, a brilliant lawyer and a wonderful force for good. He has spent his life fighting miscarriages of justice everywhere. For us, he generated such support – with even Lord Scarman writing to the American court on our behalf – that it made all the difference. He is a quite extraordinary person.”

After the Croft/Hagan case, McCooey asked if I would highlight the plight of another of his clients. Of course, I said, who? He said it was Myra Hindley. I was never as passionate as he was about having her released. I never met her so found it difficult to share his conviction that she was fully rehabilitated, but I did agree with him about one aspect of her case that was patently unfair: that the decision to release her, and prisoners like her, rested not with a judge but with a politician, the home secretary of the day.

“Whenever she got close to being released, the press would hear about it and the subsequent media outrage meant home secretaries would buckle under the pressure,” Andrew told me. “But they shouldn’t make such decisions. An independent judiciary should.”

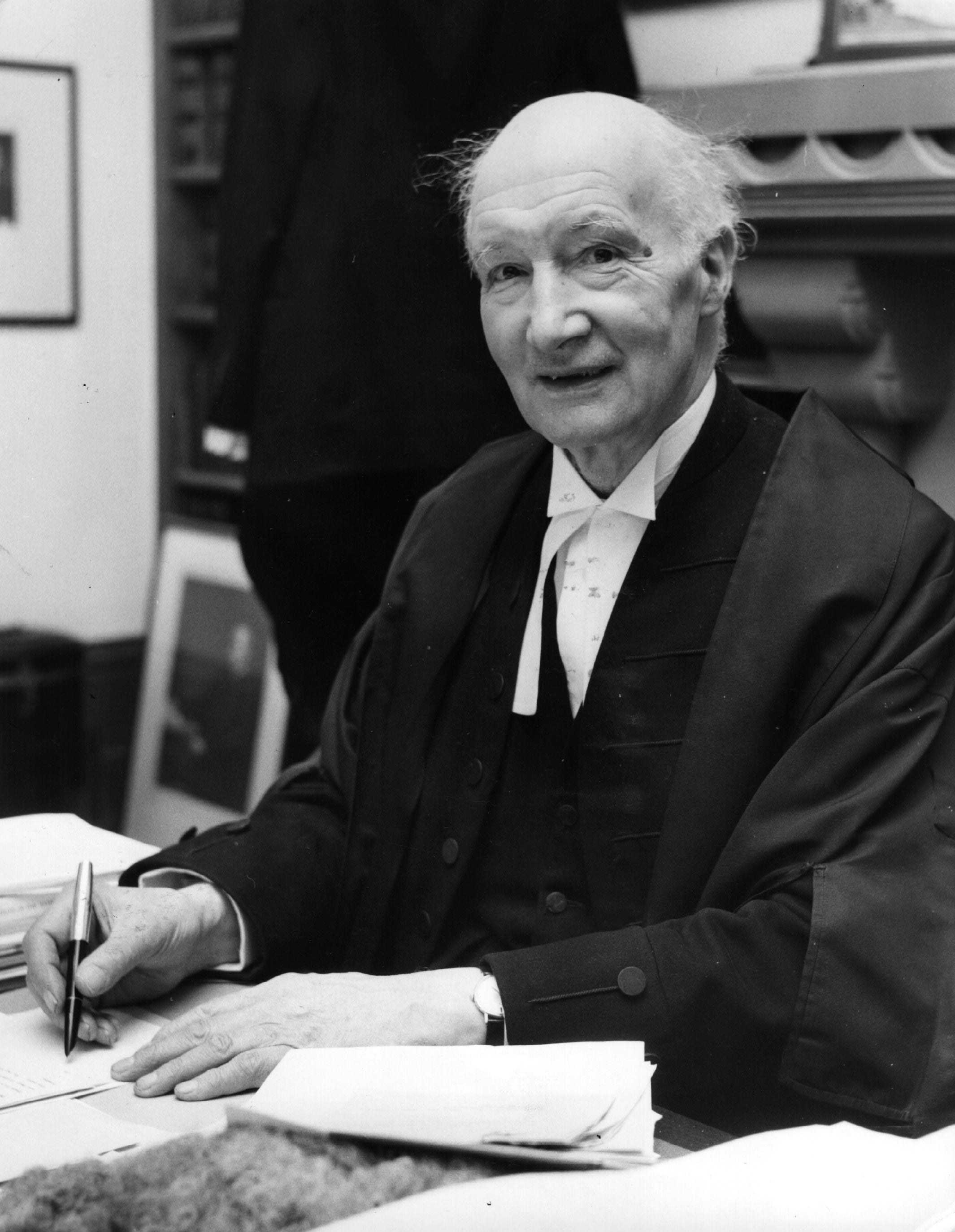

We obtained evidence that the judge who sentenced Hindley and Brady did not intend her to die in prison. Mr Justice Fenton Atkinson wrote to Roy Jenkins, the home secretary, in 1966 to say: “Though I believe Ian Brady is wicked beyond belief without hope of redemption (short of a miracle), I cannot feel that the same is necessarily true of Hindley once removed from his influence.

“At present, she is as deeply corrupted as Brady, but it is not so long ago that she was taking instruction in the Catholic Church and was a communicant and a normal sort of girl.”

I spoke to Hindley often by phone, and she wrote to me on numerous occasions. She claimed she was coerced, raped and manipulated by Brady, who, she said, threatened to kill her aunt – who had brought her up – unless she participated in their terrible crimes, the murders of five children. Was she telling the truth or was she trying to manipulate me? I never reached a firm conclusion.

When it comes to Judgment Day, it’s not about how clever you are or how important. It’s about whether you helped ... those less fortunate. My task is to stand up for such people

McCooey was convinced she had redeemed herself but he never tried to force that conviction on me or judge me harshly me when, later, I reported in this newspaper Brady’s claims from his cell that Hindley was lying. It became academic anyway; Hindley died, still in prison, in 2002.

Supported by Margaret back in their home in Sittingbourne, McCooey continued to travel the world helping people who couldn’t afford a defence. Margaret reckons he got at least eight prisoners off a variety of Death Rows.

Among his many stunning victories was the remarkable case of Stephen Owen, whose 12-year-old son, Darren, was killed under the wheels of a lorry just a stone’s throw from McCooey’s office. It turned out that the lorry driver, Kevin Taylor, who had driven off after the accident and showed no remorse, had never had a driving licence. But he was given only an 18-month sentence for dangerous driving, spent just 12 months in prison – and then returned to illegally driving lorries. There were also reports that he had desecrated the boy’s grave.

Owen reported all this to the police, and wrote to the Queen and Lady Thatcher asking them to support Taylor’s sentence being increased, all to no avail. In desperation, he acquired a shotgun and shot Taylor, wounding him. Owen was charged with several offences, including attempted murder. In a stroke of genius at the 1992 trial, McCooey advised his client to plead not guilty, even though Owen went on to admit everything to the jury. The jury freed him and he walked out of the court to the cheers of hundreds of supporters.

When I later told McCooey I thought this was a risky tactic, he simply said: “I had faith that the jury would do the right thing. That’s the very essence of justice.”

In 1997, McCooey became a higher court advocate, which meant he could represent more clients at crown courts without a barrister. In 1999 he became a judge – a recorder – a rank to which few solicitors rise. His sponsors for that role were Lord Denning, former Master of the Rolls, and Lord Scarman, renowned for his report into the causes of the Brixton riots of 1981.

Denning once described McCooey as: “A very good sort of person. One of the most energetic and able lawyers, who will work for nothing if he thinks the cause is right.”

McCooey retired in 2012. We met at the time and he told me his decision had in part been made because of painful back problems. That was later diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease. He received treatment over the years but most recently when doctors advised he needed residential care, Margaret fought to have him brought home where she has help to care for him.

He listens to Classic FM surrounded by pictures of their daughters, Juliet, 41, a solicitor, Christabel, 32, a human rights barrister, and Caroline, a human rights advocate working in Peru, who tragically took her own life in 2019 at the age of 41. He and Margaret are desperately proud of them all.

It’s time to go, but before I leave, I remind McCooey of something he once told Heather Mills, who was then The Independent’s home affairs correspondent.

“Defendants need to believe that you believe in and care for them,” he said. “When it comes to Judgment Day, it’s not about how clever you are or how important. It’s about whether you helped the least person – you know, those less fortunate. My task is to stand up for such people and do all I can to help.”

And no one can deny he did that to the best of his very considerable abilities.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments