When this is all over, Andrew Lloyd Webber may well be seen as the saviour of theatre

He says his production of ‘Cinderella’ will open today come hell or high water, and if the government wants to arrest him, so be it, theatres must be saved. David Lister reports

Two occasions when I came into contact with Andrew Lloyd Webber gave me an insight into a man, who is, not for the first time, becoming the most important figure in British theatre.

The first occurred when as an arts journalist on the Independent, I chaired the Arts Correspondents Group. I invited Lloyd Webber to our monthly lunch and sat next to him as he conversed with, and took questions from, the assembled group. It was a surprising experience. The hugely successful, multi-millionaire composer, theatre owner and impresario was shy and nervy, visibly sweating.

A few days after the event I received a letter from him, advising me how I could improve proceedings. At the time, Lloyd Webber had, rather oddly, closed down his hit musical Sunset Boulevard, rethought it and opened it up again. I rather cheekily replied to his letter, saying that he was not going to close down the Arts Correspondents Group and have it re-open with his preferred changes.

The other episode that sticks in my mind, and seems barely credible in these straitened times, was when he flew a few of us to see his most successful musical Phantom of the Opera in Basel. But it was much more than that. He flew us in a private plane, sporting the Phantom logo, and with music from the show playing throughout the journey. Plus, the idea of the Basel production was that it would run in perpetuity, the specially built theatre showing Phantom, only Phantom and nothing but Phantom to audiences from across Europe for all time.

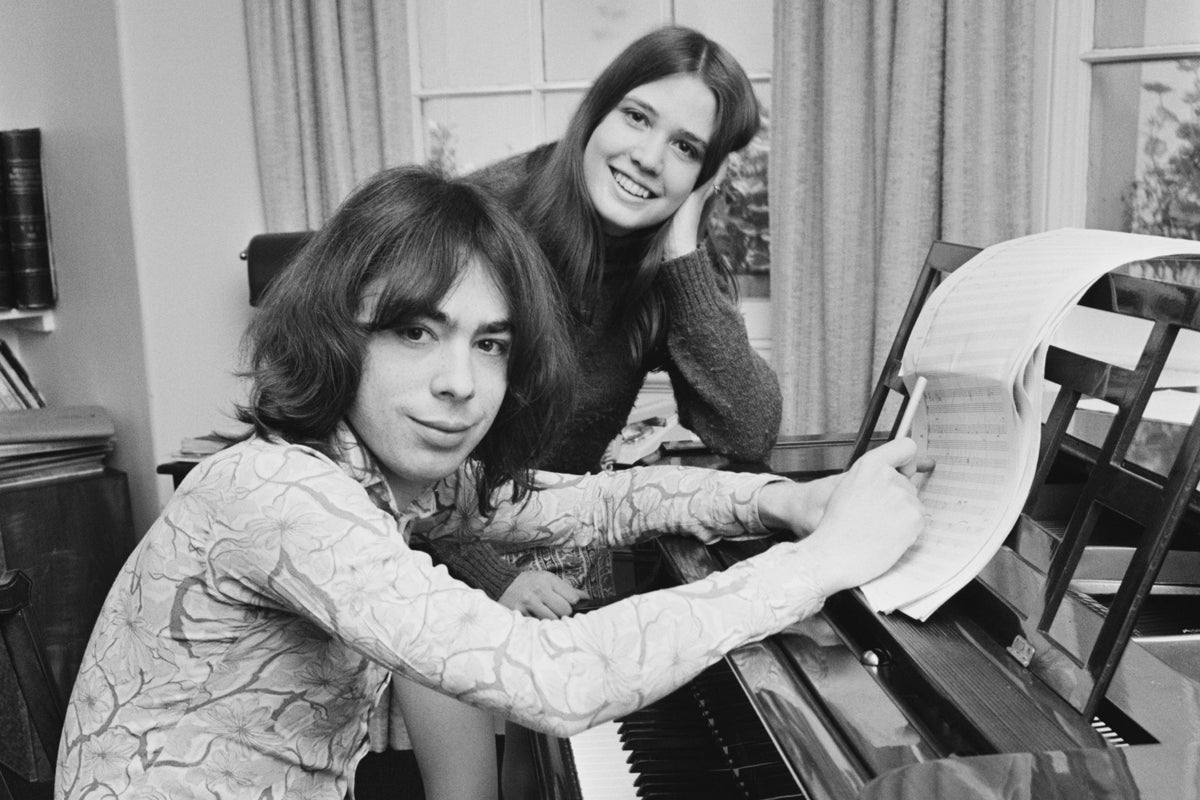

That particular musical had strong personal resonances for him, as it was inspired by his ex-wife Sarah Brightman.

Alas, the Basel theatre was an unwelcoming hangar-like building, and the production closed relatively quickly. But it was an interesting and imaginative aspiration.

Maybe, the arts establishment could never quite get their heads round a figure whose wildly successful musicals attracted coach parties rather than a cultural elite

Those two memories, in their different ways, say a lot about Lord Lloyd-Webber, and a lot about why he has been in the headlines throughout Covid and most especially in the last few weeks.

The first showed one side of the Lloyd Webber character, shy, nervy and a little defensive. The other showed the admirable entrepreneurship of the man with a mind ever bustling with imaginative concepts. Perhaps that defensiveness springs from the fact that the British arts establishment has always been a bit sniffy towards him and his music. I couldn’t disagree more, as I love his swirling, romantic, operatic and often deeply affecting scores.

Maybe, the arts establishment could never quite get their heads round a figure who voted Tory and was ennobled by the Tories, and whose wildly successful musicals attracted coach parties rather than a cultural elite. That sniffiness towards his work could certainly bewilders and upsets him.

I once wrote a piece for the Independent questioning why some in the arts had a visceral dislike for Lloyd Webber. It was baffling as not only were his musicals a massive success in box office and exports. Not only did they shift the centre of gravity for stage musicals from the US to Britain. They were, crucially – and this is often forgotten now – artistically daring.

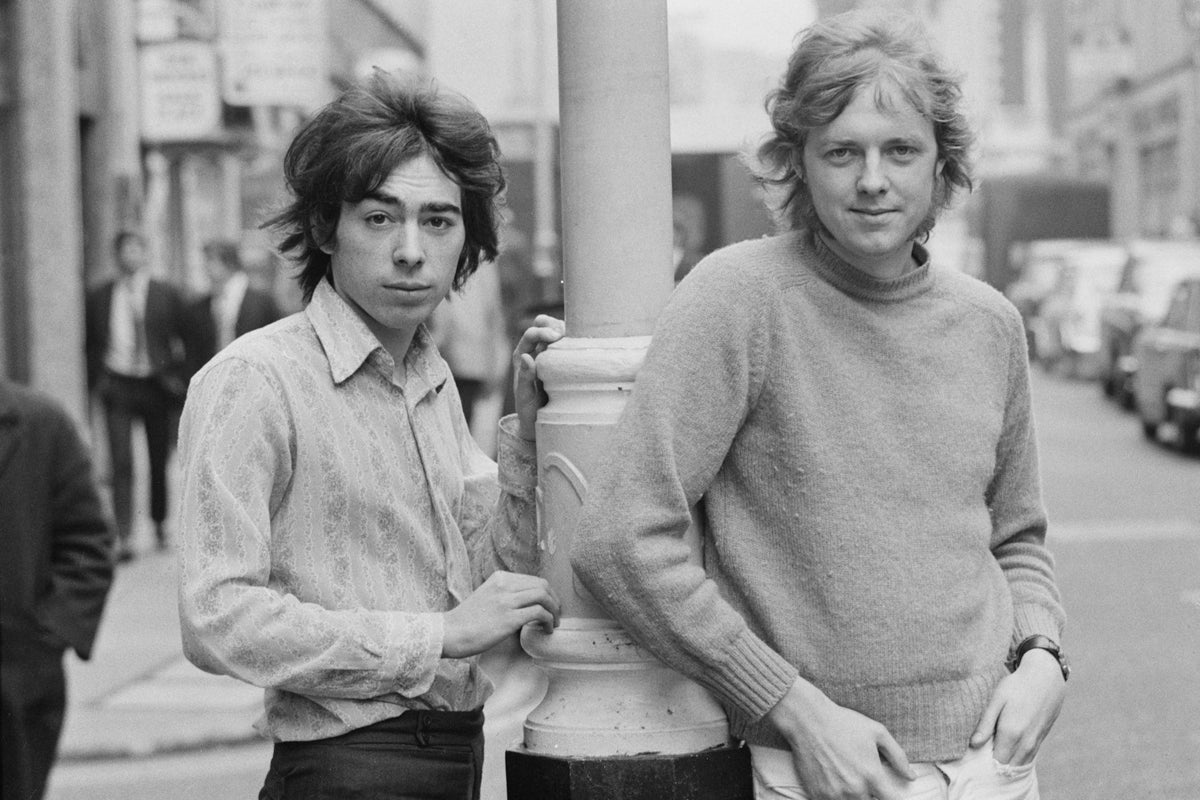

The early collaborations with Tim Rice not only presented musicals in a rock’n’roll idiom (Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Jesus Christ Superstar), they could choose a deeply unfashionable and politically incorrect subject, the fascist Eva Peron, and turn it into the global success, Evita.

The lyricist Don Black, who collaborated with him on Sunset Boulevard, was not wrong when he said: “Andrew more or less single-handedly reinvented the musical.”

For years, of course, Lloyd Webber has been a towering figure in theatre, not just because of the success of his shows, or how he has exported them around the world, but because of his buying up, restoration and renovation of key West End venues such as the Theatre Royal Drury Lane and the London Palladium.

But only since the advent of Covid has he become something rather different: the key spokesman for the art form, a champion of theatre and a man with a plan.

It marks a change to the landscape, as in general in recent decades we have looked to the titans of the subsidised sector – Peter Hall, Nicholas Hytner, Trevor Nunn et al – to make the case for theatre. True, one leading light of the commercial sector, Sonia Friedman, has voiced her concern on a number of occasions. But even she is largely a producer of straight plays. For someone whose fame, wealth and success come from musical theatre to take on the mantle of spokesman for the entire art form is unexpected, when there is still just a whiff of snobbery towards musicals from the arts world. Despite the contentment in recent decades that Lloyd Webber has found in his personal life with his marriage to former equestrian Madeleine Gurdon, the lack of acceptance and praise in some quarters hurts him.

Yet, since Covid and lockdown closed the theatres, putting their existence in peril, 73-year-old Lloyd Webber has taken on the mantle of defender of the faith. Of course, it is not without some self-interest. Two shows are about to open in his own theatres. His own new twice-delayed musical version of Cinderella is scheduled to open on 25 June. And later in the summer a musical of the Disney film Frozen is set to open at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, a venue he has lovingly restored – at a cost of £60m – to its original glory for the occasion.

As he said in an interview in The Times: “I don’t run theatres for profit. I never have. I’ve been very, very lucky. This is a way of putting something back in.”

Interestingly, Lloyd Webber’s love of theatre and particularly its buildings and architecture has led to him using his muscle against the mighty Disney organisation. He has forbidden the company from putting adverts for Frozen on the front of the theatre. “We are putting it on the building down the road,” he said, “I hate advertising on theatres. The theatre itself should be the advertisement.”

During the first lockdown it was Lloyd Webber who was prominent among those making the case for government money to be set aside to keep theatres afloat.

But latterly a new side to the composer and theatre owner has been visible. Not shy, not defensive, but direct, angry, aggressive and threatening. After all the setbacks his theatres, and all theatres, have suffered over the last year, Lloyd Webber has quite simply had enough. He will, he threatened, open Cinderella as planned, whatever government restrictions are in place and if they wanted to come and arrest him, so be it.

“We are going to open, come hell or high water, he told The Daily Telegraph. Asked what he would do if the government postponed lifting lockdown, he said: ‘Come to the theatre and arrest us’.” He added that scientific evidence showed that theatres were “completely safe” and do not cause outbreaks, adding: “If the government ignore their own science, we have the mother of all legal cases against them. If Cinderella couldn’t open, we’d go ‘look, either we go to law about it or you’ll have to compensate us’.”

Several days later he looked prepared to compromise – a little. He pleaded with ministers to increase the permitted attendance from 50 per cent to 75 per cent. Perhaps the prospect of a prison cell was becoming less appealing. But he had thought it through and had a concrete proposal to make. He suggested a bigger crowd being allowed in to his shows in exchange for audience members wearing facemasks and producing a negative Covid test in advance.

He said: “Delaying the full capacity reopening of theatres will be devastating. A 50 per cent house is not a viable solution for any length of time. At this last chance saloon, I hope the government would consider a small – and safe – step to 75 per cent capacity, with all proven safety mitigations. A small step from them, yet a giant leap for theatres up and down the country.”

His words, and perhaps his suggested compromise, were being heard in Downing Street. It was no surprise that when the prime minister gave his press conference on Monday 14 June announcing there would be a four week delay to the 21 June date for national reopening, that the name of Andrew Lloyd Webber was raised by one of the questioners. “I have colossal admiration for Andrew Lloyd Webber,” replied Boris Johnson, “and as regards Cinderella we are in talks with him about a pilot scheme.”

A pilot scheme in which performances could take place in front of an audience, with proof of vaccination or a recent test, would in other words include Cinderella. Lloyd Webber’s stance has paid some dividends, if not the full dividend he has been demanding. And, Lloyd Webber made clear to Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden when Dowden made the pilot scheme offer to him, that the scheme must not just be for him, but must be a wider scheme for the whole industry. The last thing he wanted was to be seen as part of a small elite, receiving a favour from the Tory government.

He wanted to be seen as a unifier for the industry, and the champion of it. Indeed, he was careful to say after the PM’s tribute to him: “My goal is, and will always be, to fight for the full and safe reopening of theatre and live music venues up and down the country.”

Nevertheless, some took umbrage and did indeed see it as special treatment. Craig Hassall, chief executive of the Royal Albert Hall, said he felt “bitter and twisted” about the process. He said: “Isn’t it funny that the test events being mooted now are the Wimbledon final, a car race and probably a Cinderella production by Lloyd Webber?”

For all his best efforts to be a unifier, Lloyd Webber will always be seen by some as the Tory-ennobled billionaire who gets special treatment. It’s an unfair analysis. Lloyd Webber has, over this long disaster for theatre, kept the art form in the public eye and shown that when he speaks the government and the prime minister listen. There are few others in theatre, perhaps in the whole of the arts, of whom that can be said with such certainty.

For all his best efforts to be a unifier, Andrew Lloyd Webber will always be seen by some as the Tory-ennobled billionaire who gets special treatment. It’s an unfair analysis

When a more measured history of the arts during Covid comes to written, it is very possible that he will be seen as far more than the saviour of Cinderella. Lloyd Webber may well be acknowledged as the saviour of theatre.

Furthermore, he cannot be regarded as a recipient of special treatment. For in a totally unexpected development, Lloyd Webber turned down the government offer to be part of the pilot scheme with a larger audience for his show.

He said on Friday 18 June that theatre “had been treated as an afterthought and undervalued”. He added: “I have made it crystal clear that I would only be able to participate if others were involved and the rest of the industry – theatre and music – were treated equally. This has not been confirmed to me.”

So Cinderella will open with a 50 per cent capacity audience. And what of the defiant assertion that he was determined to play to bigger houses and risk arrest? He explained that it would mean his cast, orchestra and indeed audiences also risking arrest, and he couldn’t countenance that, adding: “If it were just me, I would happily risk arrest and fines to make a stand and lead the live music and theatre industry back to the full capacities we so desperately need.”

No wonder a government source said: “We are bemused that Lloyd Webber has decided not to take part in the ERP (Events Research Programme).

“This would have given him the opportunity to have audiences at 100 per cent for Cinderella and at the same time play a crucial part for his sector in the fuller reopening.

“It’s baffling that he’s pulled out and is instead opening his theatre at 50 per cent given all the noise he’s been making about opening fully and threatening to sue.”

Yes, but that’s Lloyd Webber for you. Baffling, defiant, provocative, sometimes contradictory, sometimes divisive, but always prepared to go out on a limb for the art form he loves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments