Alcohol in No 10? ‘God, it was a bloody dry old do in our day’

Anji Hunter, one of Tony Blair’s closest advisers, talks to students about the differences between New Labour and the current government – noting that in contrast to Blair, Johnson never takes advice from previous prime ministers. By John Rentoul

Tony Blair’s former officials have been WhatsApping each other in amazement at the revelations of workplace drinking in No 10 during lockdowns, Anji Hunter told our class at King’s College London last month. “God, it was a bloody dry old do in our day,” they commented to each other.

“Honestly, none of us can remember ever having a drink in Downing Street,” Hunter said. “I remember Tim Allan [deputy director of communications] had a leaving party, an official party in the White Room, you could invite guests, and people went around with trays and drinks, and you’d have one or two. But that was it. And there were a lot of young people in there and quite a hard drinking culture, after work. It wasn’t like it was full of prissy people. But when we were there, we worked.”

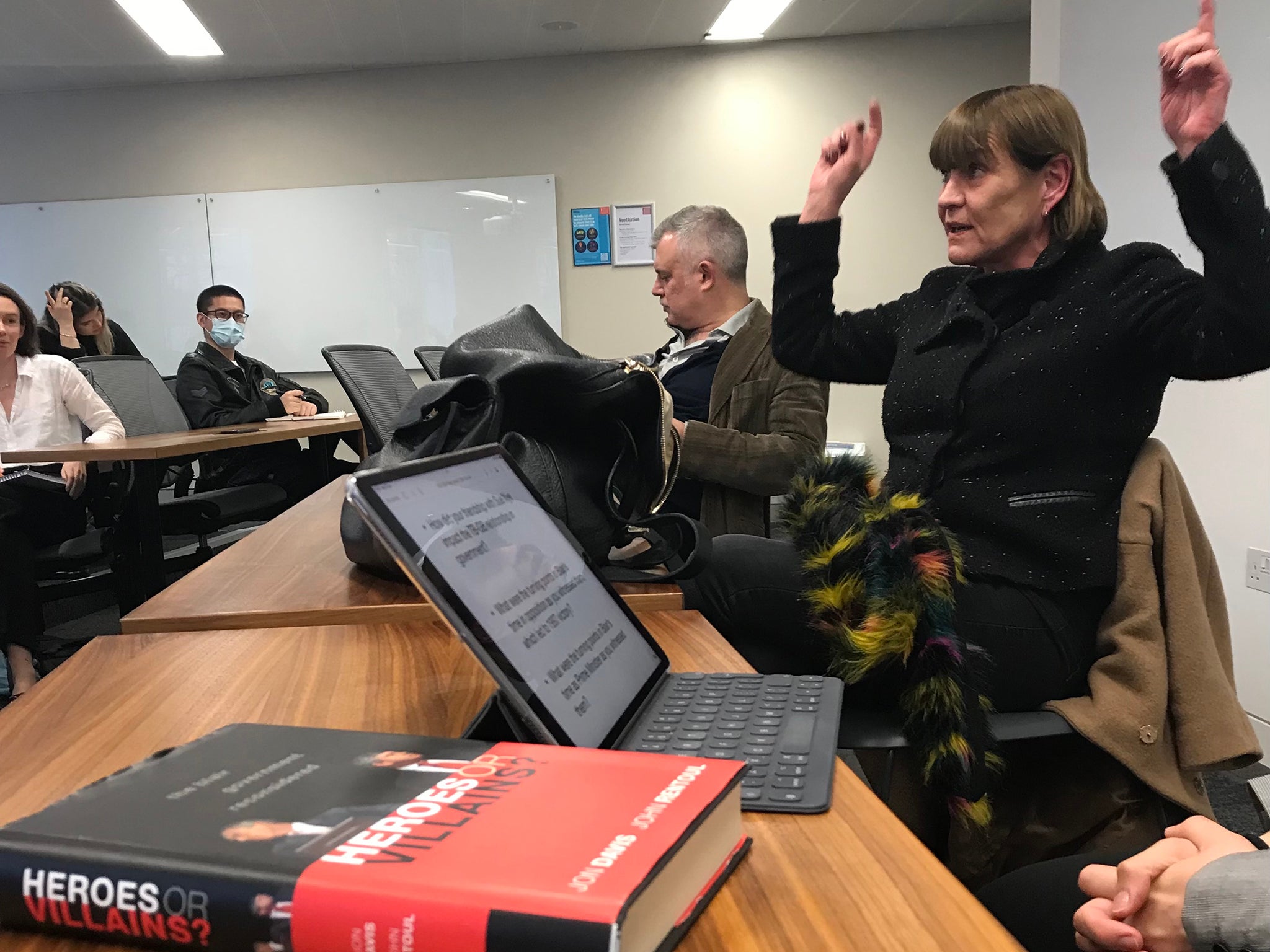

Hunter, who was research assistant to Blair in opposition and director of government relations during his first term as prime minister, came to talk about the New Labour government – and how different it was from the current one – to the “Blair Years” class that I teach with Dr Michelle Clement and Professor Jon Davis. Since she was last a special guest at one of our classes, she has become a TV star, in last year’s Blair & Brown: The New Labour Revolution, the BBC documentary.

One of the ways in which Boris Johnson is different from his predecessors, she said, is that he doesn’t seem to take advice from them. Blair was a “great fan” of Margaret Thatcher, she said, and would “phone her for counsel at tricky times; and she would willingly give it”. There is a prime ministers’ club, she said: “They help each other out, and it’s totally discreet.” One of the students asked if Blair had been asked for advice by Johnson. “I don’t know; he was giving advice to Matt Hancock at the beginning of the pandemic, regularly. He would definitely take a call from Boris Johnson – but I don’t think Boris would ever call him. He just couldn’t bear to.” But if he did ring, Blair would give him advice, she said.

She also thought that Blair was different from Johnson in his “desire to take as many conflicting views as possible”. Whatever the issue, “he wanted to get people in to say, ‘No, we shouldn’t be doing that.’ He wanted to hear the arguments; that’s the lawyer in him.” That wasn’t the only difference: “Once he had taken all these views, he would reflect, and prepare, prepare, prepare. And no complacency. You’ve got to prepare for everything. This is so the opposite of Boris Johnson, with his cavalier attitude. Tony would prepare for everything; really worked, thought about his position all the time, and the best way to get what he needed done.”

Hunter explained how she came to work for Blair, whom she had known at school and in Oxford, when he was at university and she was at a sixth-form college, in the House of Commons in 1986. “I went to work for him briefly and he said, ‘You’ve got to come back to me full time.’ So I go back to work for him full time as his research assistant. On my first or second day there I said to him, ‘What do you want me to do?’ He had just got his role in the [shadow] trade and industry team, and he said, ‘I want you to be my alliance-builder.’ And I thought, ‘That’s something I could do.’”

As Blair rose through the ranks of the Labour Party, she helped him build alliances with MPs, journalists, media proprietors and interest groups – the fabric of the New Labour “big tent”. She said she was “set” by Blair to “court” Conrad Black, the owner of the Telegraph group, Rupert Murdoch, owner of The Times, The Sunday Times, The Sun and the News of the World, and Lord Rothermere, Vere Harmsworth, father of the current owner of the Daily Mail. The high point of the courtship was a weekend trip halfway round the world to a conference of Murdoch’s News International executives on Hayman Island, Australia, in 1995. By the time of the election, The Sun urged its readers to vote Labour, while the rest of the formerly Conservative press was in a state of armed neutrality.

Guys can get a bit blokeish. And women can do things I think in a more subtle, discreet, quiet, and very effective way. We have our ways

In government, one of Hunter’s roles was to act as a channel of communication between the Blair and Brown camps. Her friendship with Sue Nye, an adviser to Gordon Brown, had been forged in the 1992 election, when Nye worked for Neil Kinnock, the Labour leader, and Hunter was seconded by Blair to work for her. “I was basically Sue’s assistant in ’91, ’92. And I learnt a hell of a lot from her. She’s ruthless, but charming; very political; very astute; and also had an eye for detail; that attention to detail was a very good lesson.” Hunter said that so much of election and event planning is defensive: about spotting possible pitfalls or embarrassing backgrounds for photos: “My name is WCS, Worst Case Scenario.”

The hours after Labour’s defeat in the 1992 election – the fourth defeat in a row – were critical in Blair’s rise to the leadership, and, according to Hunter, in framing his relationship with Brown. Blair’s view was that the party was “not radical enough”.

She said: “We weren’t. We hadn’t reformed the party enough. That was the main thing. He took away that the organisation was good, but there was not a good enough appeal to middle England. Before the ’92 election, he and Gordon were very frustrated. They didn’t think that we were going far enough. And he said, they both knew we were going to lose the election. I was working on the campaign and I hoped against hope that we would win it. But they knew, and he was already talking to Gordon and saying it can’t just be John Smith. ‘We can’t just give it to John Smith.’”

Smith, the shadow chancellor, was the leading candidate to succeed Kinnock after the 1992 defeat, but Smith was concerned that further dramatic changes would divide the party.

“But Gordon would never contemplate standing against John. And I thought Tony was going to – when they all went to have this chat – I thought Tony was going to say, ‘We should miss out John Smith; go straight to Gordon’ – and Tony would have backed Gordon. I remember waiting at home for news of what was going to happen. I’d been working on the campaign and honestly, working on a general election campaign is relentless, it is 24/7 for six weeks; you get like one or two hours sleep a night; and I remember I had just got home, I hadn’t seen my husband or kids for six weeks – and I got this call from Tony and he said, ‘Are you rested?’ And I said, ‘Not really.’ And he said, ‘I’ve got a new job for you: you’ve got to run Margaret Beckett’s deputy leadership campaign.’ I said: ‘What? What’s gone on?’ He said: ‘That’s what you’ve got to do. You all right?’”

Instead of Brown running for the leadership with Blair as his deputy, Brown had thrown his lot in with Smith, who immediately chose Beckett as his running mate, in order to shut down any thoughts on Blair’s part that he might still run for the deputy leadership.

However, the bond between Hunter and Nye was to serve Labour well in government: “I have a huge admiration for her,” said Hunter. “She’s still my best friend. And we see each other all the time.” She said she would text Nye straight after the class and tell her that the first question from the students was about their partnership. “I totally trusted her. And Gordon totally trusted her, and Tony totally trusted me. She’d be helpful to me. I remember once, Alastair sent Gordon an absolutely terrible memo, by hand; he got some poor Downing Street person to go around to the Treasury with this private note. And I rang Sue up and I said, ‘Sue, intercept it and put it in the bin.’ And she said, ‘Can I have a look at it first?’ She said, ‘You were right; it definitely went in the bin.’

“Being able to help each other out, when things were so tetchy between them – and with no disrespect to the gentlemen in the room, guys can get a bit blokeish. And women can do things I think in a more subtle, discreet, quiet, and very effective way. We have our ways.”

She said she and Blair put a lot of weight on loyalty, “driving into people a sense of commitment: you commit to me; I’ll commit to you”. She said she has a “razor-like beam” on the subject. “If it picks up something, they’ll be talked to: ‘Are you worried about something?’ You can do it nicely.” Not a culture of fear, then, asked a student. “Not a culture of fear. I don’t think people feared me.”

What about Clare Short, the international development secretary? “I was always very friendly with her, I liked her. And so did Tony. Alastair had a thing about Clare Short, but not Tony and certainly not me. I went out drinking with her.”

Another student asked what was the nature of Alastair’s “thing” about Clare Short. “He doesn’t mind me saying that. He might have admitted it himself. He was slightly misogynist. Alastair’s diaries – I’ve not read them cover to cover – when I first read them, I rang him up and said, ‘You know, there were three of us in these meetings.’ It’s basically him and Tony: him and Tony here; him and Tony there. I said: ‘There were three of us.’ He said, ‘Weren’t you always off making tea?’ Of course, I laughed my head off because he meant it in a funny way. But there’s a tiny bit of that. I love him, and we are really, really good mates. And we rib each other all the time. But yeah, there was a bit of that.”

John Major is really interesting on this: he said the worst thing about being prime minister was having to bestow these ghastly peerages. They hate all of this stuff

She was asked where her loyalty lay when Blair made Peter Mandelson resign. “I stuck absolutely by Peter in that. Robert Harris, the author, is Peter’s great friend, and a friend of mine as well, you know, I made him my friend. And when the furore was going on, Robert pops up on telly, defending Peter, saying, ‘This is an absolute outrage.’ And Alastair said to me, ‘Ring him up; ring up your effing friend Robert and tell him to get off the airwaves.’ And I did. It was the worst thing I’d ever done in Downing Street, the most treacherous thing I did. I said: ‘Robert, I don’t think you should be saying this.’ And you can imagine what Robert said. I think it was two words. Rightly.”

Another student was intrigued by Hunter’s comment that she had “made” Harris her friend. How do you make someone your friend? “I’m open. I’m honest. I’m fearless. I’m not frightened by anybody. And I was so consumed with the idea of doing the right thing. And building these alliances for him. I would – not exactly ‘do anything’, but I really worked hard at it. I’m good at making friends anyway. It’s not like I decide, ‘Oh, I’m going to make that person my friend.’

“But the Robert thing, I partly wanted to make friends with him because you don’t want them to write terrible things. You know, they’re journalists. I mean, I married a journalist.” (She is married to Adam Boulton, the former Sky News political editor.) “I bloody love them. I do. I’ve got nothing against journalists at all. But Robert, he was Peter’s friend. Alastair did not like him or trust him. And Robert persuaded Peter Mandelson, and Peter persuaded Tony, that in the ’97 campaign, Robert was going to come along for the ride, along with the leader and his team. Guess who was given the job of befriending Robert? And making sure that Robert was on board – that’s how it was: ‘Anji, you’re looking after Robert.’ So there were great photos of Robert and me jumping out of helicopters, and he became one of the team. You know, just because he got so enthused by it. You can suck people in just by absolute enthusiasm.”

That heady euphoria didn’t last, of course, and Harris became disillusioned with Blair, eventually writing a poisonous novel, The Ghost, obviously based on Tony and Cherie. Harris’s disaffection echoes that of the general public, and a million people have recently signed a petition to oppose Blair’s award of a knighthood of the garter.

“I don’t think he is that unpopular, actually,” said Hunter. “I think you’ve got to get your heads around this. There’s this unholy alliance between the right wing and the left wing. The Daily Mail and Momentum are as one: let’s do in Blair. And it’s an extraordinary alliance. It pops up; goes back; but it’s strong at the moment. I have to say, there may be a million people signing this petition saying he shouldn’t get this [knighthood]. He just lets all this stuff go over now. He has to. He can’t be in a position where these things get to him.”

We asked her what she, once a youthful rebel who was expelled from her private boarding school for being “agin the system”, thought of the knighthood? “I think it’s fantastic. It’s a thing, whether we like it or not. This is a thing. I mean, you should read him [Blair] on peerages. He thinks the whole thing is dreadful. John Major is really interesting on this: he said the worst thing about being prime minister was having to bestow these ghastly peerages. They hate all of this stuff. They don’t think it’s democratic.

“However, this one is in the gift of the Queen. And he has a massive respect for the Queen. And if the Queen’s private equerry, principal private secretary, Edward Young, rings him up and says to him, ‘I have a message from the Queen: she would like to bestow this on you,’ in my view, I’m afraid you can’t say no. Maybe I’m establishment, too establishment; maybe he is, as well. Also, the other thing is: it’s a blocker. May can’t get it until he does. Gordon can’t get it either. The Mail were already building up about that, saying, ‘Bastard, he’s holding these people up from getting their garters.’ That’s what they were doing, and now…”

She tailed off, and allowed us to finish her sentence about the hypocrisy of the Daily Mail, complaining when Blair didn’t get the knighthood, and then complaining when he did.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks