Britain promised to take 3,000 refugee children. So far it’s taken 220

The death of Alan Kurdi in 2015 spurred the government into action, but efforts have stalled, reports Katy Fallon – and campaigners say ministers need to do much more to protect unaccompanied minors waiting for help in France

On 2 September 2015, a three-year-old Syrian child, Alan Kurdi, drowned in the Mediterranean while his family was attempting to cross the short distance from Turkey to the Greek island of Kos. Alan’s death sparked an international debate about how to deal with refugees and migrants making their way across Europe, many via dangerous means.

Four years later, organisations working with displaced people in northern France are concerned about how the lack of available legal routes into Britain are pushing unaccompanied children to risk their lives crossing the English Channel. In August two people, an Iranian woman and an Iraqi man, drowned on separate attempts to cross to the UK.

“We know that children should be arriving in trains and not under them; and sat on a ferry not underneath a lorry inside a ferry; and that’s what the kids are wanting. They would rather have a safe way into the UK,” Maddy Allen, the field manger for Help Refugees in northern France tells The Independent.

Refugee Youth Service, a UK-based group which works with unaccompanied child refugees, has recently been in contact with children as young as nine and 10 years old, who have arrived in northern France hoping to get to the UK. These two children, Farzaad and Mateen* are the youngest that the service has worked with. They are just a few years older than Lord Alf Dubs was when he arrived at London Liverpool Street, 80 years ago on the Kindertransport, at the age of six. Lord Dubs has taken a leading role in pushing the government to act over child refugees.

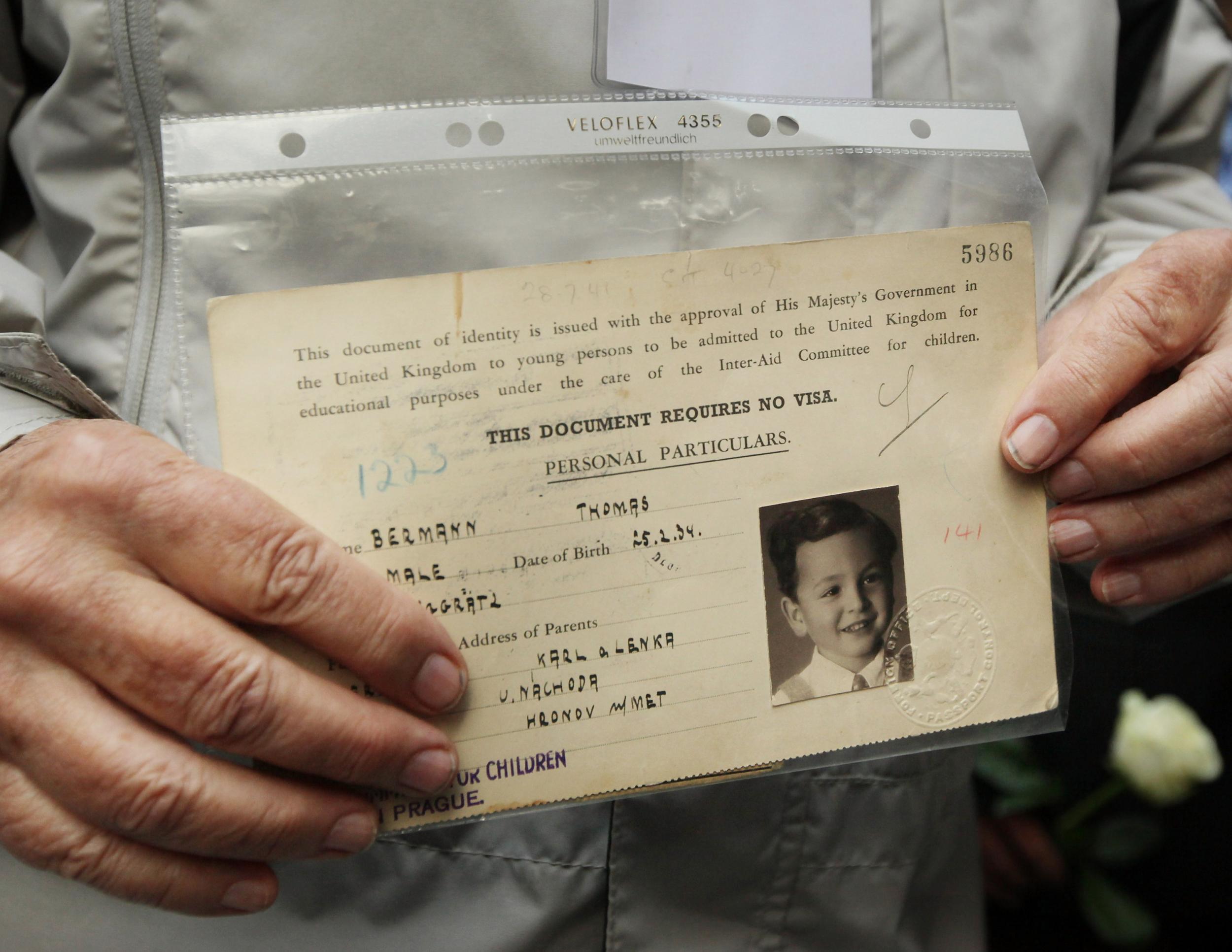

The Kindertransport, an initiative by the British government, brought 10,000 Jewish refugee children to the UK from 1938-1939. This was in response to, Kristallnacht, a Nazi-organised pogrom which destroyed Jewish homes, hospitals and schools in November 1938 in Germany and German-occupied territories.

On 21 November 1938, home secretary Sir Samuel Hoare announced that the UK would take in an unspecified number of unaccompanied Jewish refugee children. Sir Nicholas Winton, often referred to as the British Schindler, helped in the rescue of 669 Czechoslovak children. One of these children was Lord Dubs.

Lord Dubs, a little less than 80 years later, would find himself dependent on the goodwill of another home secretary, Theresa May. Lord Dubs proposed creating an amendment to the Immigration Act of 2016, which would provide sanctuary for unaccompanied children seeking refuge in the UK. This is during the period often referred to as the “refugee crisis’’ when the United Nations reported the biggest movement of people since the Second World War.

“Theresa May asked me into her office and asked me to absolve the amendment,” he says. “She said if these children come, others will follow; and I said we can’t leave these children in terrible conditions, sleeping rough and with no one to protect them, vulnerable to criminality, prostitution, trafficking. We can’t just turn our backs on them.”

Lord Dubs says that Alan Kurdi’s death changed the government’s attitude. “Theresa May summoned me back again and said they proposed to accept the amendment.”

The death of the Syrian boy was seen as a watershed moment for the perception of the refugee crisis. The photograph of his body, washed up on a Turkish beach, made the front cover of six national British newspapers, led by The Independent. In the aftermath of this, Lord Dubs was given hope for the success of his amendment. “The immigration minister phoned me up and said, we propose to accept the spirit and the letter of the amendment,” Lord Dubs pauses, “But I don’t think they’ve done any such thing.”

Initially envisaged as bringing in 3,000 child refugees, the Dubs amendment was capped at 350 places. This number increased to 480 in 2017 after the government admitted that due to an “administrative error”, 130 places had been overlooked.

Beth Gardiner-Smith, CEO of charity Safe Passage, says they were initially hopeful about the Dubs amendment: “I think there was a real sense of optimism that parties from across the political spectrum had come together and been united in this issue”. Safe Passage campaigns for safe and legal routes to the UK for unaccompanied minors. Gardiner-Smith says that after hearing there were fewer places made available than had been initially suggested their mood changed. “That was the first disappointment.”

In February 2017, the government announced that it would close the Dubs scheme. Home secretary Amber Rudd stated that it acted as a “pull” factor. Gardiner-Smith rejects this justification. “If you ask any person working with children on the move nobody would say a child has ever said to them, ‘The reason why I’m here in Europe is that I’ve heard of this thing called the Dubs scheme.’ There is no evidence for that,” she says. “Why children make desperately dangerous journeys is that they are leaving a situation that is even more desperate.”

Jemal, 17, is one of the estimated few hundred unaccompanied child refugees currently living between Calais and Dunkirk. Originally from Eritrea, he has made the journey of thousands of miles alone. He left home in 2014 at the age of 12. He sits on the kerb of a disused car park in Calais, watching his friends play football. The evening is warm and sunny. He has the wisps of a moustache on his upper lip but the eyes of a child. “I had to give my fingerprints in Italy… they weren’t nice to me there,” he says. “I have friends in Calais but it’s still sometimes scary,” he admits. “The police come everyday, they teargas us and beat us. This happened in my first few weeks of being here, just when we were sleeping.”

He has lived in Calais for eight months, which have been marked by his interactions with the police. “It’s like Tom and Jerry,” he says.

Jemal has hopes for the UK: “I would like to study, perhaps medicine because I like science and I think I’m good at it.” Jemal speaks seven languages, among them English and Arabic. “I learned English along the way,” he says. He shouts in support of his friends playing the intense game of football. “I support Manchester United. Marcus Rashford is my favourite player.”

Jemal is here to get to the United Kingdom. “It’s dangerous to get to the UK but it’s worth the risk,” he says. “You can’t stay here. I want to go to the UK for a better life. I hope that they will treat me better.” Jemal says that he left home because he had to. “Eritrea is very beautiful but for people like me, they force you to do military service, and that’s the truth,” he pauses in between the joyous cheers of a friend who has just scored a goal. “I want to be free, not to be a soldier for a lifetime like my father or my brothers,” he adds. “The police here don’t care, they think we are enemies but we are refugees you know, not criminals.”

The hostile environment is a concern to Lord Dubs, who is actively campaigning for unaccompanied children in Europe and in particular northern France. “Calais is now like Fort Knox,” he says.

The UK has contributed significant funds towards border security at Calais. In January 2018 it agreed to pay £44.5m in extra security measures to prevent another refugee camp arising in the area. Freedom of information requests in April 2017 showed that the government had spent £316m between 2010 to 2016 to deter illegal immigration in Calais and the surrounding region.

One of the issues around the Dubs amendment is what charities consider to be the relatively small number of places made available for it. In 2018 charity Help Refugees challenged the process the Home Office used to establish the number of places for minors in the Dubs scheme, calling it “seriously defective”. It lost this challenge but the Court of Appeal ruled that reasons given to child refugees in Calais who were rejected for the scheme were “patently inadequate”, and required the Home Office to provide more detailed reasoning for their rejection.

There is evidence from freedom of information requests made by Vice that local authorities offered significantly more places, 1,572, rather than the 480 places which were ultimately offered for unaccompanied minors. The first transfer of children under the Dubs amendment began in October 2016 after the closure of the Calais refugee camp. Organisations have told The Independent that they have struggled to get accurate figures about how many of the 480 Dubs places have been filled to date.

When asked about how many children had now been transferred under the amendment, the Home Office replied: “Over 220 children were transferred to the UK under section 67 when the Calais camp was cleared in late 2016, however we are not providing a running commentary on numbers.”

Stephen Cowan, leader of Hammersmith and Fulham council, says he considered the government’s approach to the Dubs amendment flawed. “I wouldn’t say it’s a failure because the government didn’t even try. Look at what they did at crucial points and it’s clear that rather than implementing the Dubs scheme they tried to scupper it from the start. It’s only through the work of Lord Dubs, Safe Passage, Help Refugees and other campaigners that any children have been saved.”

Cowan says that councils such as his would be able to do more if they were given support. “Many councils have joined together to tell the government that if they guarantee to pay the full costs of looking after these desperate children, thousands more can be saved. That’s exactly what great British governments have done in the past and it’s what this government needs to do now.”

Maddy Allen who works on the ground in northern France with Help Refugees agrees. “It’s important that we don’t frame that as a success because it’s been a massive failing that we can’t even transfer 480 children,” she says.

Greece, Italy and France were designated as the three countries where minors could be eligible for the amendment. Conditions for unaccompanied minors are under scrutiny in Greece after news that in Moria refugee camp, on the Greek island of Lesvos, one child was killed during a fight with another unaccompanied child in a designated “safe zone”. Charities alleged that conditions in the camp have lead to this death.

“The safe zones, as well as all other sections, are severely overcrowded. Provision of services is scarce and inefficient. Incidents go unattended and create more tension. The staff and organisations can’t cope with the numbers,” Better Days, a charity which works on Lesvos, said in a statement. Moria has a population of more than 10,000, which is 10 times over its official capacity.

In Italy, Marta Welander, executive director of Refugee Rights Europe, told The Independent that conditions are little better. “Poor reception conditions and frustration with lengthy procedures, resulting from the large volume of asylum applications received, mean many unaccompanied minors attempt to cross the border into France to either claim asylum there or to continue on to another European country such as the UK where they may have relatives or other support networks.”

Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, notorious for his uncompromising stance towards migrants and asylum seekers, reluctantly agreed to let 27 migrant teenagers disembark from a rescue ship on to the island of Lampedusa in August. He said this was in spite of it being “divergent to my orientation”.

After making the journey through countries such as Greece and Italy, many unaccompanied minors arrive in northern France with their sights set on the UK. “I don’t really sleep at night because I’m trying to get to the UK,” says Mazar, 17, from Iraqi Kurdistan. He has a large smile and is tall and long-limbed. “I still have family in Kurdistan,” he says, “but I had to leave because I had a problem.” Mazar says that he will not give up trying to get to the UK. “I hope I can study to become a mechanic when I get there.”

He has heard this week that the large disused gym in Dunkirk where he is living with 900 others, of which 130 are unaccompanied minors, will be closed. “I don’t want them to close the gym,” he says quietly, looking at his temporary home.

Gardiner-Smith says legal routes to the UK are essential for the welfare of unaccompanied children seeking asylum. “If we don’t want to see children risking their lives, whether it’s in the Mediterranean, or in Libya, or in the Channel itself we need to be offering safe and legal routes. We are a country that has managed great things internationally and diplomatically and the fact that we’ve still seen so few children come through this scheme is depressing and disappointing.”

Aazar, 17, from Afghanistan, says that living in northern France is difficult. “I’ve been here for two months and life is not good,” he says in nearly fluent English. “The reason I want to go to the UK is that it’s better for children. It’s not good in France, they will put you in a camp.” He says his family is still in Afghanistan but he made the long journey alone. “It’s very dangerous there, I saw a policeman killed in front of me, there are bomb blasts everyday.”

“I love biology, I will try to be a doctor,” he says. “I will try the trucks; it’s scary and dangerous.”

Azar enjoys cricket. “I like cricket a lot. I support the English cricket team.” He has cousins in the UK but he knows of no other way to get there other than the dangerous methods he’s been trying. “There are no legal ways possible for me I don’t think,” he says, “but if there were it would be great.”

Like all the other minors who spoke to The Independent for this article, Aazar also says that he won’t give up trying to get to the UK.

Magid Magid, the Green MEP for Yorkshire and the Humber who came to the UK as a child refugee himself, says that he thought more children should have been taken under the Dubs amendment. “I’ve got a lot of admiration for Alf Dubs and I had the privilege to spend some time with him. He’s someone who has dedicated his life to this.”

“I think we keep forgetting unaccompanied minors aren’t just statistics. It’s just really difficult; and we’ve all got a role and responsibility in it.” he says. “In comparison to other countries, say Germany, we’re quite awful in accommodating people,” he says. “Our happiness and relative safety doesn’t and shouldn’t come at the expense of equality and opportunity for everyone else.”

Magid suggests that there are elements of racism at play. “God forbid it was Australian, American or white European children. They would not be in the same situation that these black and brown children are in at the moment. The people of Britain are full of love and compassion and are really able to, and want to, welcome these child refugees in.”

When asked why it had not yet filled all the spaces for Dubs, a Home Office spokesperson replied that: “The UK has made a significant contribution to protecting vulnerable children, providing protection to more than 39,500 children since the start of 2010. In 2018, the UK received the third highest number of asylum claims from unaccompanied children in the EU. We remain fully committed to relocating 480 children under section 67 and are continuing to make progress to achieve that objective.”

The Home Office stated that in the year ending June 2019, the UK received 3,496 asylum claims from unaccompanied children, a similar number to that received in Germany.

As well as the lack of legal and safe routes, one of the issues raised by campaigners is the inadequate process to report missing migrant children. “Government-imposed restrictions prevent the European hotline for missing children in France from taking on cases of missing migrant children. This is morally unacceptable. In other countries such as Greece, the hotline operates as intended and treats all missing children cases, migrant or not,” says Aagje Ieven, secretary general of Missing Children Europe.

Brexit is another issue. “Brexit has sucked the life out of politics,” says Lord Dubs, who admits it’s difficult to lobby for changes among such political turmoil. “People say why don’t Muslim countries do something? Well there’s a million in Turkey, four million in Lebanon. I make that five to six million… we are arguing about a handful,” he says.

Alan Kurdi drowned on the journey from Bodrum to Kos, a distance of 2.5 miles. The Channel is 20.7 miles at its shortest distance between the UK and France and at least 80 children have crossed the channel in boats this year.

There is light, however, for some who have made it over on the Dubs scheme. Mohamed, 17, was previously living in a refugee camp in Greece. He is currently being cared for by a local authority in the West Midlands.

“I was so happy when I found out I could come to the UK, because it meant I could have a good life,” he says. “My eyes were really damaged because I have diabetes and I lost sight in one eye. I had to wear dark glasses. But here the doctors gave me special contact lenses, which cover the damage. Now I feel much better and my diabetes is under more control.”

Stella Creasy, Labour MP for Walthamstow and a vocal supporter of the Dubs amendment, says the government had failed to live up to its word on the issue. “There are children living in squalid conditions on our doorstep because this country made a promise and failed to honour it. Three years ago we said we would help 3,000 of the child refugees in Europe through the Dubs amendment, and only 220 have been able to come here to safety.

Many more are still sleeping rough and at risk of violence or exploitation, with some as young as nine, all alone and frightened. “Without providing a safe and legal route for these children to travel it’s likely many will risk their lives trying to cross the Channel or be lost to the traffickers. The Home Office wants us to give up on these children and pretend they don’t exist. If we let them, all of us should hang our heads in shame.”

Lord Dubs says that the Kindertransport set an important precedent about how the UK deals with unaccompanied refugee children. “I don’t think I would have survived the Holocaust,” he says. “One thing about Kindertransport was that Britain was the only country that took them. America said no and Europe shut its doors.”

“I still believe whatever the attitudes to migrants as a whole, people in Britain are sympathetic to child refugees, providing one explains the situation; and I think politically we can take more and I argue we should take our share, not take them all – we can’t – but our share.”

Lord Dubs says that he will keep putting pressure on the government to do more for child refugees. “We think the government has not delivered on its words; and I think they’ve abdicated their responsibilities.”

* All names have been changed to protect the identities of the minors

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks