It took Cambridge more than 600 years to allow the first women through its doors

Girton College opened its doors to women 150 years ago today. Olivia Campbell looks back at the battle waged by middle-class women to attend university, study the same courses as men, and finally be awarded a degree

On 16 October 1869, the doors of Girton College, Cambridge, opened wide for the first time. Formidable feminist campaigners had fought, hustled and campaigned to establish the UK’s first residential college that allowed women through its gates. Five of them, possessing considerable intelligence, began their first term at university – and changed the very nature of women’s education. One hundred and fifty years later, it’s hard to imagine not being able to access a decent education simply because you were born the wrong sex.

In 2018, women were storming their way across university. Data shows that 57 per cent of all students in higher education were female. Statistics from Ucas revealed that 98,000 more women than men applied to university. However, this road has been long, complicated and defined by the unwavering resilience of the women who recognised their right to learn. “In a way, the opening of Girton changed everything,” says Professor Susan Smith, who has been the mistress of Girton since 2009: “It opened a doorway and was part of an unstoppable movement across the UK whereby women were seeking to improve their participation in wider society.”

Originally named the College for Women at Benslow House, Girton was an experiment in how far women with a desire for knowledge could go. The University of Cambridge, which had been founded more than 600 years earlier, was known for its prestige and renowned worldwide but remained woefully sexist. To get women into this institution had the potential to change women’s lives forever.

Entrance exams were held in London in July 1869, in which 18 candidates entered. Sixteen of them would pass, despite many originating from poor educational backgrounds. When term first started three months later, five women entered the grounds and began their education. The impact was significant. Between October 1869 and June 1900, at least 725 students attended the college, setting a precedent for women everywhere.

So who exactly where the Girton girls? Emily Gibson (1849-1934) was the first applicant to start at the college, having intellectually outgrown the limited education that had been previously available to girls. Next was the slightly older student, Anna Lloyd, who ended up dropping out before her residency ended. Like many female students, she faced considerable scorn from her sisters for pursuing an education and eschewing the domestic activities that were expected of her. Isabella Townshend – Gibson’s sister-in-law – also dropped out in 1872. She was described by fellow students as being “artistic” and was perhaps better suited to the arts.

Inspired by the pioneering legacy of Girton, Dame Louisa Innes Lumsden (1840-1935) was particularly gifted. She originally attended the Edinburgh Ladies Education Association, where she took part in lectures but was not allowed to go further. After being a student at Girton until 1872, she became a tutor for 1873-74. Beyond Girton, Lumsden’s reach was significant. A stint as a headmistress at the progressive St Leonards School in Fife, from 1877-82, and a job as warden of University Hall, Scotland’s first residential hall for women, followed. If this wasn’t enough, she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by St Andrews University in 1911 and was made a dame in 1925.

Finally, we come to Sarah Woodhead (1851-1912), who was the first women to sit and pass the prestigious Tripos examinations. A Tripos refers to the examinations that would qualify a student to gain a bachelor’s degree – initially the only way to obtain one was to complete a mathematics Tripos. Woodhead did exactly that, gaining the equivalent to a first-class honours in the subject. To say she was a trailblazer would be accurate.

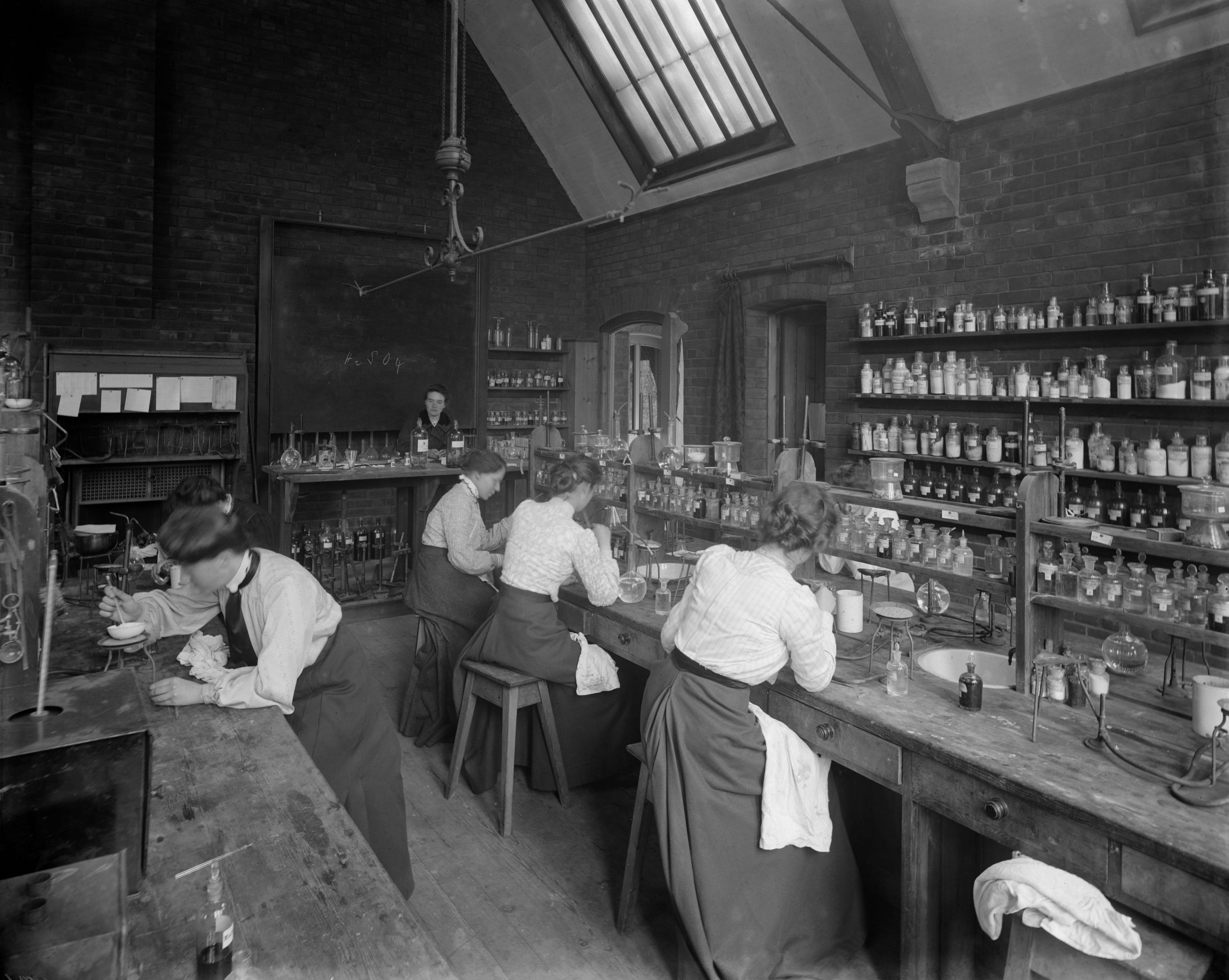

Woodhead, Lumsden and Rachel Scott (1848-1905) became the first three to complete a Cambridge Tripos at the same level as their male counterparts. At a time when women were seen as intellectually inferior to men, such academic achievements were unprecedented. The three became known as the “Girton Pioneers”. Between 1869 and 1900 there were as many as 10 different subjects in which at least one student had passed Tripos examinations. This was of particular significance – women were able to take the same subjects as men, even if they were still unable to officially get a degree.

“The insistence of Emily Davies [one of the founders of Girton] that women should study the same subjects as men was an important principle,” says June Purvis, an emeritus professor of women’s and gender history at the University of Portsmouth. “Creating ‘separate’ and ‘different’ education for women could always be seen as second-rate. Also, by not studying the same subjects as men, they would not be able to compete for a professional career. The founding principle of Girton was that different education can never be the same as equal education.”

The insistence of Emily Davies that women should study the same subjects as men was an important principle. The founding principle of Girton was that different education can never be the same as equal education

The college was established following a tiresome joint effort from aforementioned suffragist Emily Davies (1830-1921) and Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827-1891). Inspired by the same goal, their aim was to create an institution in Cambridge that allowed women to study full-time at degree level, just like the opportunities that were given to men. Before managing to secure £7,000 in funding in 1871, the college was originally based in Hitchin, Hertfordshire. The location was strategic – it was still close as to make clear that the founders were gunning for female participation, but not so close as to scare the male chauvinists who feared women “tainting” the good masculine name of Cambridge.

Both women were heavyweights in the fight for female emancipation. Bodichon was the daughter of radical politician Benjamin Leigh Smith (1783-1860), a son of radical abolitionist William Smith. From a young age she was exposed to the world of radicals and political campaigners, so the transition into feminist pioneer was natural. Davies came from a humbler background as the daughter of an evangelical clergyman. She was drawn to the fight after spending time with the Ladies of Langham Place, a social group that Bodichon frequented often to discuss women’s rights.

Even before Girton, these women had made considerable waves to advance women’s position in society. Bodichon established the first ever Women’s Suffrage Committee in 1866, which was a precursor to the movement spearheaded by the Pankhursts and many other female activists. She also worked tirelessly to challenge stringent divorce laws, campaigned for greater working rights and helped develop the English Woman’s Journal.

Davies, on the other hand, built her activism around learning. “Education was a constant struggle for her,” says Susan Smith. “She forged on in the wake of opposition and simply wouldn’t compromise. She wasn’t just about lectures for ladies. Formal education had to be on the same terms as men.” Whether this was taking the same examinations or accessing the same curriculum, educational equality was something Davies pursued doggedly.

She forged on in the wake of opposition and simply wouldn’t compromise. She wasn’t just about lectures for ladies. Formal education had to be on the same terms as men

Her work on the London School Board and in the Schools Inquiry Commission was instrumental in obtaining the admission of girls into local secondary school examinations, something which transitioned further into fighting at degree level.

Bodichon and Davies met through the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, an organisation set up by the former alongside Jessie Boucherett and Adelaide Anne Proctor. Together, they lamented that they could not go to Cambridge and set out to do something about it. Their start came in 1865 when Cambridge officially opened local examinations to girls. Why should this not extend to obtaining degrees?

The long, slow journey for greater education continued. By 1871, land had been acquired and the college moved to the village of Girton where it stands today. Costing £12,000, the college finally had a home and has earned its position as a pivotal part of women’s education.

The push for access to Oxbridge institutions was largely spearheaded by women from the middle and upper classes, who were concerned about future economic struggles. “The push for women to get into universities was intimately linked with their desire to earn a living,” Carol Dyhouse, an emeritus professor and social historian from the University of Sussex, tells me. “Ironically, industrialisation gave working-class women more professional – although often exploitative – work opportunities.”

By the 1840s, many young middle-class women found themselves unmarried and needing to earn a living. An 1851 census found that 26 per cent (nearly three million) of women over the age of 25 were unmarried; by 1871 this figure had risen to more than three million. This demographic became known as “surplus women” and suffered from the stifling effect that traditional Victorian gender roles caused.

Women were not deemed marriageable if they tried to find work. It would not be wrong to say that they were essentially trapped.

“Apart from the poorly paid overstocked job of being a governess, the range of occupations opened to them was very limited,” says Purvis. “Many were motivated by the desire to learn and to enter other professions, but their education, which put emphasis on social priorities, prevented this.”

Teaching at schools and institutions became a particular area of campaigning for women, but in order to get the same opportunities as men, they had to pursue a more formal education. “Women in the 19th century were very much second-class citizens,” says Purvis – and it was essential that women proved they were not just going to sit in the background.

The path to gaining higher education was plagued by obstacles. “There was a prevailing separate spheres ideology that caused significant resistance to women entering university,” Purvis says. It was expected that middle-class women should remain “ladylike homemakers” and stay as “creatures who were relative to men rather than individual beings in their own right”. This pervasive notion, of women as simply domestic homemakers had an oppressive effect upon nearly every facet of Victorian society. The fight for education was a severe blow to this deeply rooted ideology, and thus faced resistance at nearly every opportunity.

“It was a common belief that an educated woman would not be able to manage a household or have knowledge, as one commentator put it, about ‘pies and puddings’,” Purvis continues. “There were some who argued that the energy spent studying would shrink women’s breasts so that they would be unable to breastfeed a baby, even if they were lucky enough to catch a husband.”

Women who dared seek an education were vilified and often had to make significant sacrifices to their social reputation. The derogatory term “bluestocking” entered the cultural vocabulary and was used to disparage intellectual women. They were depicted as “frumpy” and not beautiful enough to be graced with a husband.

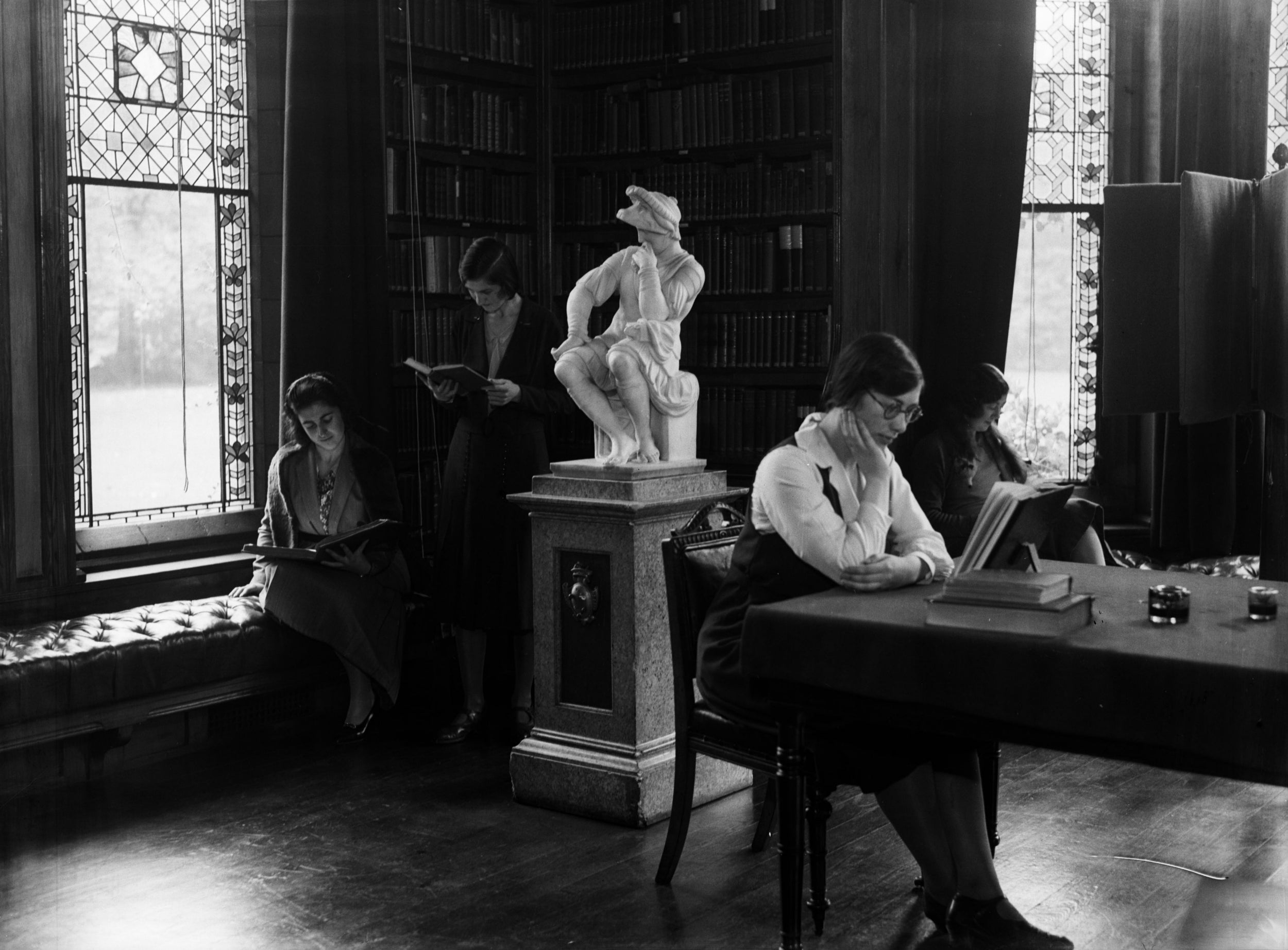

Those who found themselves at Girton – or at any of the other institutions that were slowly allowing women in – also found that their experiences were vastly different to their male counterparts. The idea of universities as places where you could let off steam or engage in activities that could be called hedonistic was different in reality.

“Slight deviations from good behaviour could blow up into nasty affairs,” Dyhouse says. “Towards the end of the century there were many scandals when women didn’t behave in the modest and constrained way they had been burdened with in Victorian society.”

Women were chaperoned to lectures that were taught by men and were forced to adhere to strict regulations about how they could socialise with men. Davies was particularly aware of the scrutiny that Girton was under and sought to control outside opinion at all costs. Dancing into the early hours of the morning wasn’t an option for the first Girton students. “If a student showed herself to be a ‘women of the world’ she was out on her ear because of the double standard within education,” Dyhouse says.

There were some who argued that the energy spent studying would shrink women’s breasts so that they would be unable to breastfeed a baby, even if they were lucky enough to catch a husband

However, for all of Girton’s pioneering, Purvis asserts that “universities were still strongholds of masculine privilege” in England. Despite fierce campaigning, Oxford and Cambridge dug their heels in and refused to award women the same degrees as men. Female students were only granted this right at Cambridge in 1947 – nearly eight decades after Girton opened its doors.

Oxford did however relent earlier in 1920, and women were allowed to officially be matriculated and graduate. However, they were only granted this because Oxford believed that Cambridge would do the same. What followed was an institution that desperately tried to backpedal out of fear of being viewed as less masculine – and therefore less prestigious. Oxford ended up voting in favour of a statute that limited the quota of women students.

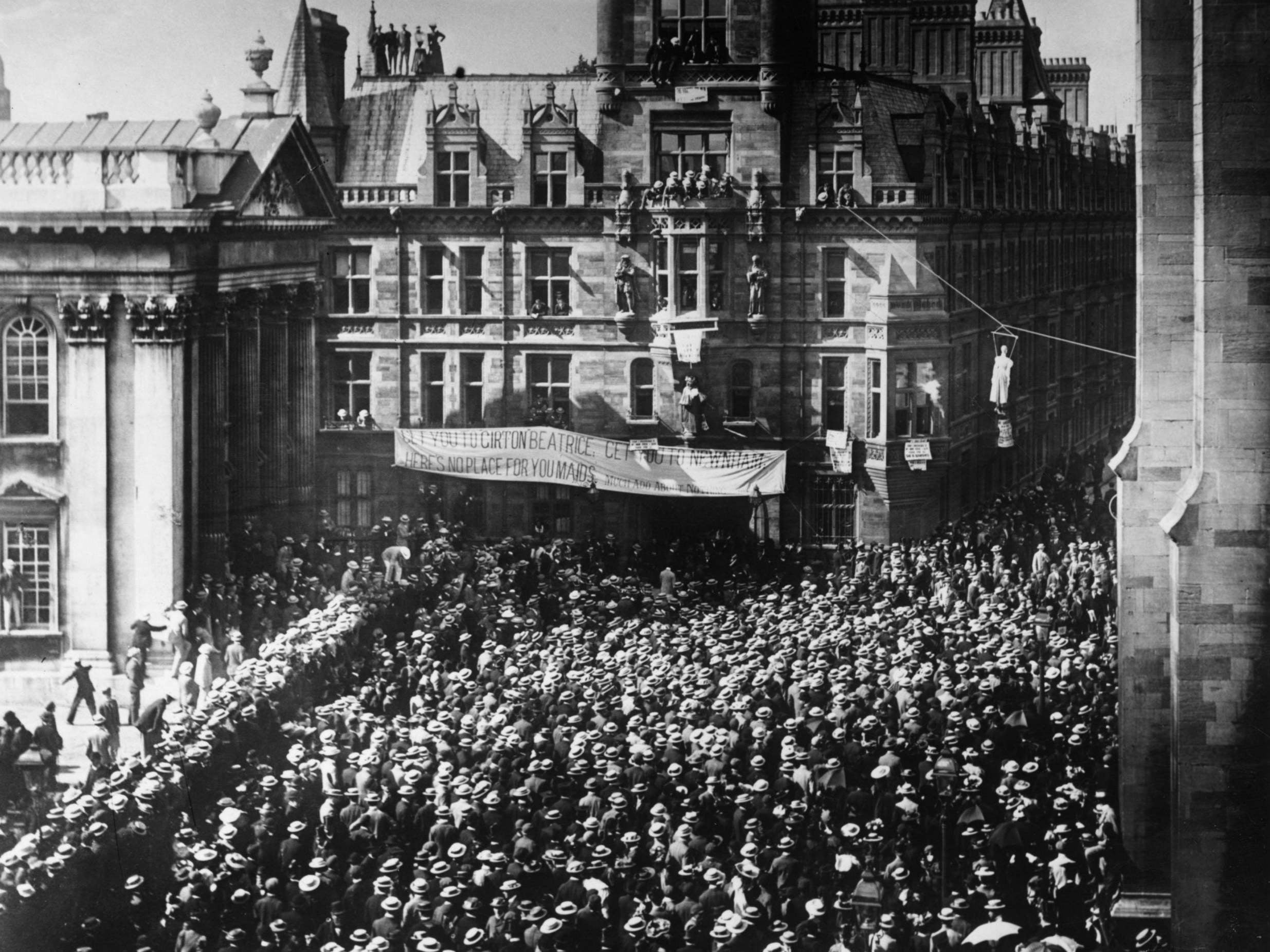

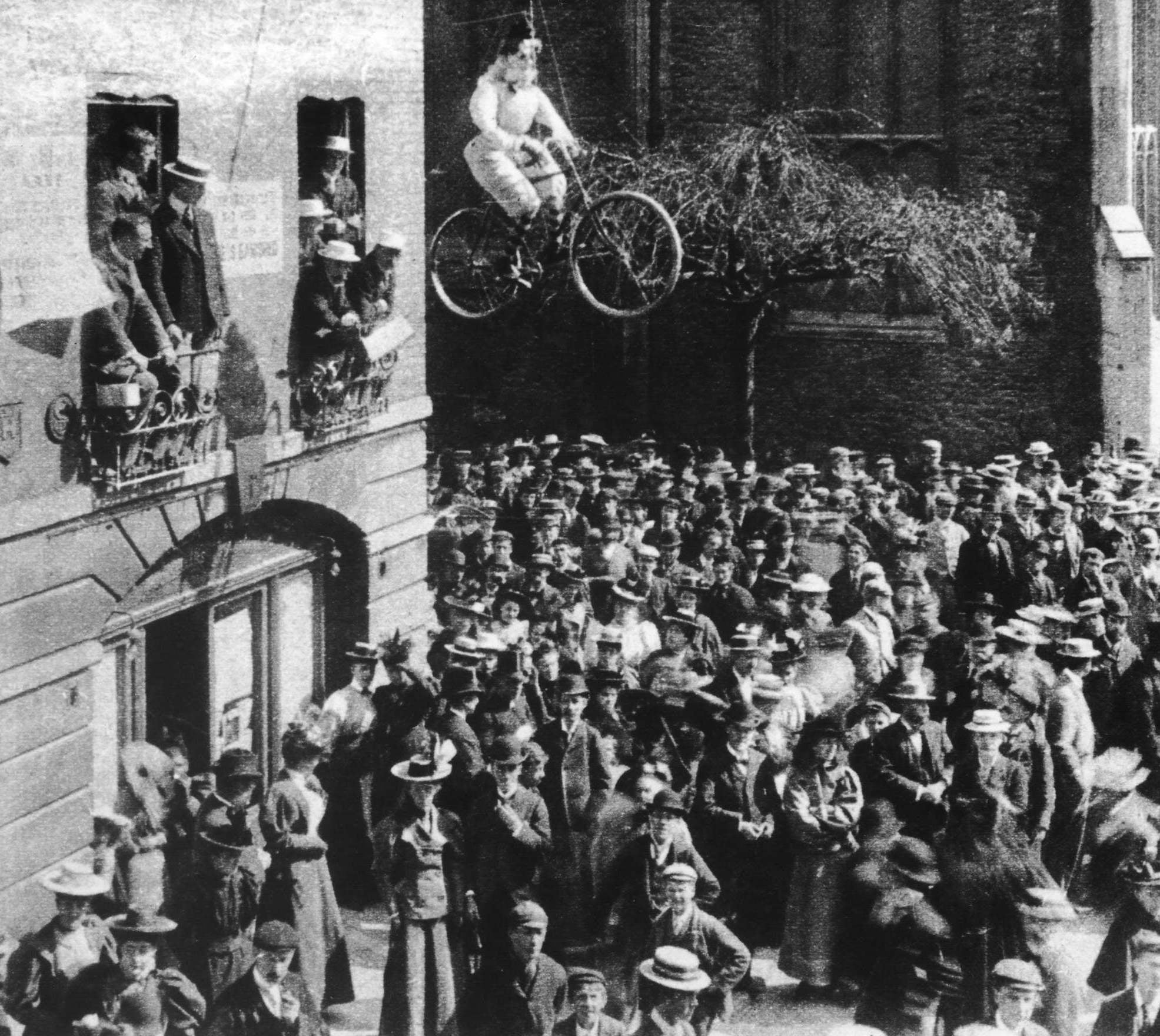

The subject of degrees at Cambridge was debated fiercely, and “every time women pushed to have full entitlement to degrees, there were terrible scenes”, Dyhouse explains. The most notorious incident occurred in 1897 after a motion for full membership was defeated with 1051 against it. In scenes that would shock feminists today, male chauvinists, elated by success, took to the city’s Market Street with an effigy of an aforementioned “bluestocking”. After hearing the result, they mutilated and burnt the effigy.

Other universities also capitulated way before Cambridge did: the University of London in 1878, Durham University in 1895 and the Scottish universities in 1892 all offered degrees.

It is worth mentioning that the original site of Girton was chosen by Davies and Bodichon as it carried less risk and was less likely to cause controversy. “In a sense [campaigners] were originally hedging their bets because they didn’t actually know whether they would gain access to Cambridge,” Smith points out. “They were pushing on all the doors and it was ultimately a question of which door would open first.”

Nonetheless, in 150 years of standing, more than 15,000 students have walked through the doors of Girton College. Notable alumni include Arianna Huffington, co-founder of The Huffington Post; and Margrethe II, the queen of Denmark. What started out as a notion that women should receive an education equal to men proved that a powerful idea can change what people thought was possible.

The education we have the privilege of accessing today would not exist without the relentless effort of women in the 19th century, who fought doggedly and often at great sacrifice. The legacy of Girton, which proved that women were every bit as intelligent as men, will be remembered.

“Girton put the idea of a women’s college into popular imagination,” Dyhouse asserts. “It wasn’t just a pioneer for opening up opportunities for women, it was actually an important move to change what people thought was possible in a culture. In building Girton, it gave weight to that image in the cultural imagination.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks