‘I wanted to reclaim the art of the nude’: Renee Saliba on Manet’s ‘outrageous’ painting Olympia

No one entity can control what a woman is. And just as Manet broke through a mould set before him, I could break through the mould set before me, Renee Saliba tells Christine Manby

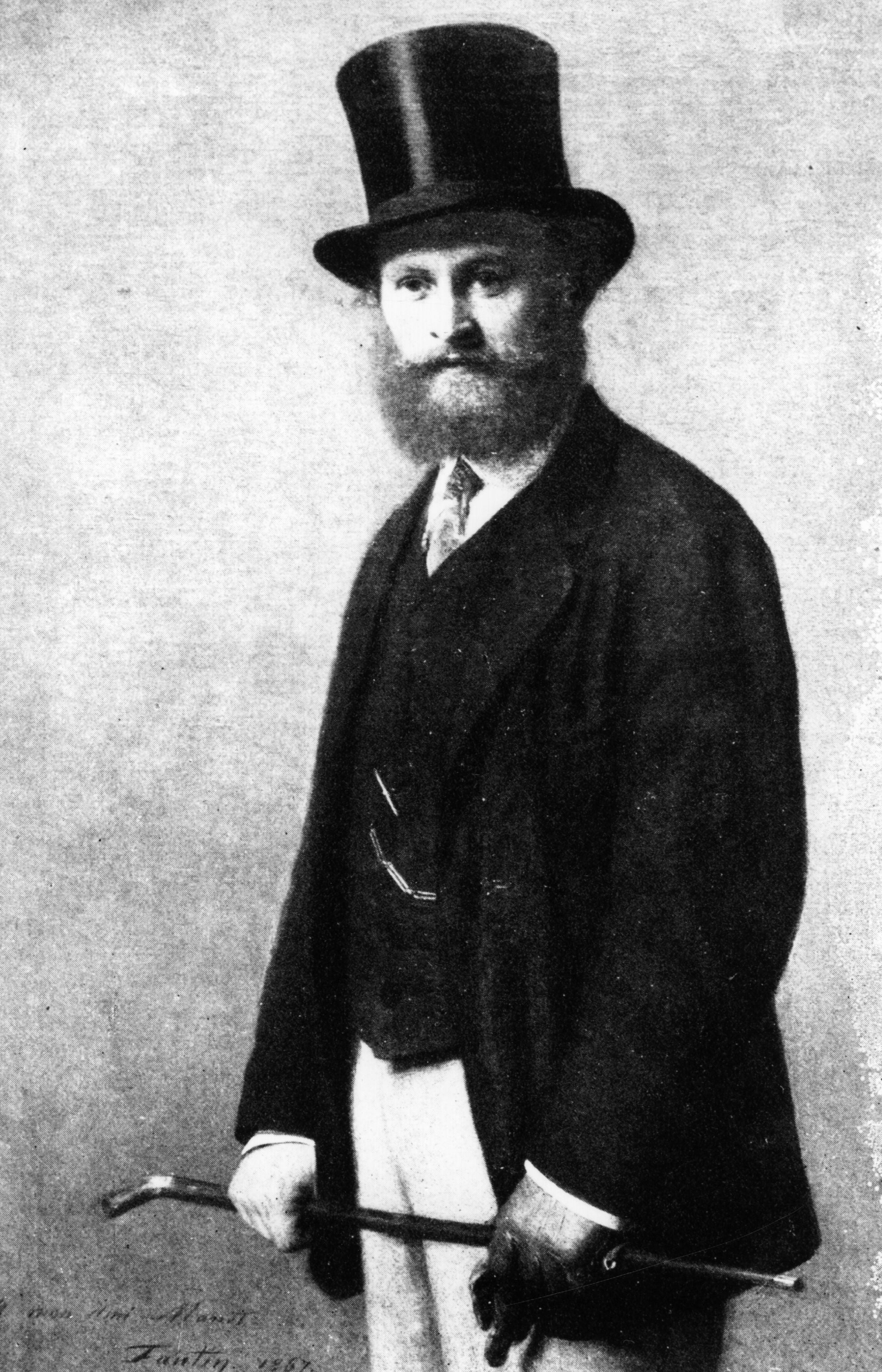

It’s not often that a naked woman holds all the power, but when you look at Edouard Manet’s famous painting Olympia, it seems his model does exactly that. As she reclines on a chaise, wearing nothing but a black ribbon around her neck to emphasise the whiteness of her skin, her gaze is direct and challenging. Manet’s painting outraged Parisian audiences in the 1860s. Five years ago, it inspired artist Renee Saliba to harness the power of that challenging gaze in her own art and life.

Saliba grew up in Australia, where she spent a lot of time with her grandmothers, who had emigrated from Italy and Malta. “I was raised on old-world traditional Catholic views. My grandmothers believed in beautiful food and furniture. They always made sure to put on lipstick. But they were judgmental when it came to ‘how a lady behaves’. Our family was run according to strict gender roles. From an early age I was interested in running my own business but was encouraged to pick up more household duties while my brother was encouraged to join my father at work.”

“The women in my family struggled with depression and anxiety. There was always a conflict between self and society for the women in my family. My mother tried to start a number of careers but was always being called away to deal with the kids. Seeing her struggle encouraged me to build up a rebellious nature.”

To that end Saliba chose a career in art, studying visual communications, photography and fashion. “I wanted to immerse myself in design and beauty and conceptual thinking.” Upon graduating, she worked for an Australian streetwear brand, designing menswear. But Saliba found the creative scene in Australia did not inspire her in the ways she’d hoped. She decided to move to London, hoping to find inspiration there. “But I got another job in menswear.”

Saliba’s first year in London was difficult. She was frustrated that, having moved to London to “change everything”, she had slipped into a life that was more or less the same as the one she’d left behind. In an attempt to reboot her creativity, she picked up her camera again and began to do some soul-searching. She also rekindled her interest in the Renaissance, “which means rebirth”, and in particular in the long tradition of the female nude. “I loved the freedom of nudity but it was always from the perspective of the male gaze. I wanted to reclaim the art of the nude and create my own from the perspective of the subject. That’s why I fell in love with Manet’s Olympia.”

Manet’s Olympia caused a scandal when it was first shown in 1865. Olympia was a pseudonym frequently used by prostitutes of the time and Manet had included several details in the painting to underline that hint. As Saliba explains: “Olympia was a direct rip of a painting by Titian called Venus of Urbino, which was a beloved painting from the Renaissance. In the eyes of religious and cultural expectations for paintings, Manet basically corrupted the image.”

Where Titian had painted a dog, to represent fidelity, for example, Manet painted a cat at Olympia’s feet, to suggest the opposite.

Saliba continues: “The ways in which Manet flips the technical expectations on its head to create Olympia leave you feeling very different when you look at the two paintings side by side. Titian’s Venus is warm and inviting whereas Olympia is cold, tense and almost makes you feel shame for intruding in on her.”

Manet wasn’t the only artist to closely reference Titian’s Venus, as Saliba noted when she investigated further. “All of these paintings, but in particular Manet’s, taught me that no one entity can control what art is. Once I was able to dive into my own story and why this struck me so much, I was able to see that it was about more than creative expression. It is really about how I see myself and my own story. No one entity can control what a woman is. And just as Manet broke through a mould set before him, I could break through the mould set before me.”

Empowered by this revelation, Saliba set up “Lethally Her” (https://lethallyher.com), which she describes as “a brand that provides product, events and content to inspire female artists and creators to attain their highest level of bad-assery. We are a community focused brand that imparts members with practical know-how on building a self-directed career and skill set in living autonomously. Our aim is to provide a safe space for our community to be able to celebrate the female creative with a future-forward focus.”

Forget ‘tonal contrast.’ We know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one

Writing on the Lethally Her website, Saliba says: “Every year we see more females choosing creative arts subjects, but a smaller number of females go into creative jobs after graduation. What is the reason behind this? Why have we not started to see a more equivalent proportion of women to men in creative fields? Why do women hesitate to become painters, musicians, illustrators, film directors and architects? The doors of the creative world seem to give warm welcomes for men and cold shoulders for women and other minority groups. There are so many supremely great female artists and creators, many intriguing and innovative ones who remain deficiently represented or appreciated.”

Manet’s model for Olympia would have appreciated Saliba’s efforts to expand opportunities for female artists. She was Victorine Meurent, an artist in her own right, whose paintings were regularly shown at the Paris Salon. But Meurent is of course not the only woman in Manet’s painting. Standing behind the courtesan is a black woman, her fully dressed maid. Manet used another professional model for this figure. She is described in his notebook as “Laure très belle négresse 11 rue de Vintimille 3e”.

When Olympia was first shown, Laure’s presence in the painting went largely unremarked except as a stylistic conceit. It was as though Laure was quite literally “part of the background”, there merely for the purposes of chiaroscuro. But though slavery was abolished in the French empire in 1848, the prejudices of the early 19th century undoubtedly persisted when Laure was posing for Manet. Black feminist Lorraine O’Grady wrote in her 1990s essay Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity: “Forget ‘tonal contrast’. We know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one … She is the chaos that must be excised, and it is her excision that stabilizes the West’s construct of the female body, for the ‘femininity’ of the white female body is ensured by assigning the not-white to a chaos safely removed from sight. Thus only the white body remains as the object of a voyeuristic, fetishizing male gaze.”

O’Grady’s essay raises the point that far more interesting than Olympia’s defiant gaze, which is traditionally seen as two fingers to the patriarchy, is Laure’s “oppositional gaze” as she looks at Olympia. A term first used by bell hooks in her 1992 essay The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators, it refers to the oppression of black people’s right to look – black slaves could be punished for looking at their white masters – which made simple observation a rebellious act. As hooks wrote: “There is power in looking.”

Manet painted Laure at least three times. In 2019, the Musee D’Orsay officially renamed Manet’s painting La Négresse from 1863 Portrait de Laure. Artist and model are believed to have met in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris, where Laure, who was working as a nursemaid, often took her charges. It’s thought she may also have been one of the models in Jacques-Eugene Feyen’s Le baiser enfantin, which was painted a couple of years after Olympia.

In 2018, Laure was captured on canvas once more by French American artist Elizabeth Colomba, for her show Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. Colomba’s portrait of Laure, titled Laure (Portrait of a Negresse) shows her on her way to Manet's studio. Laure is pictured in a beautiful pink dress, topped with a blue cape with gold buttons. She carries a red umbrella and an embellished bag in her gloved hand. Talking to Vogue, Colomba said: “I give her centre stage and a lightness of being that I’m not sure she had at the time.”

In the background of Colomba’s painting is the figure of white Englishwoman Cora Pearl, one of the most successful courtesans in 19th century Paris. Pearl’s face is unformed and indistinct. A black cat walks by her. It’s a clear reference to and a neat reversal of Olympia, as Laure gazes out from the portrait with a serenity and confidence that inspire every bit as much as Olympia’s defiance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks