The chefs changing the problem with diversity in restaurant kitchens

We may have a wealth of different cultures that are well represented by on our high streets, from Japanese to Argentinian and everything inbetween. But why doesn’t the workforce in them reflect this, asks Clare Finney

“I’m writing this from the kitchen, and right now I’m watching the hot line work; guys from Greece, Poland, Brazil and Italy working in synergy,” writes Taylor Sessegnon-Shakespeare, head pastry chef of Tavolino in London. She was brought up in the UK, but her maternal grandmother is African American and her father’s family are Jamaican. “To my right, an Antiguan man works back to back with an Italian woman. They’re laughing, they’re joking – everybody is one, there is a sense of unity.”

It’s a beautiful image – and one which, up until recently, I imagined to be fairly typical of Britain’s restaurant scene.

Sure, more rural restaurants were unlikely to be models of diversity, but metropolitan restaurant kitchens were bound to reflect the make-up of the city’s population – far more so than other industries I thought. Only when I came to speak to Sessegnon-Shakespeare for this feature did I realise quite how hopelessly naive I had been.

“I am really confused as to where the illusion that restaurants kitchens are manned by a cohesive motley crew came from,” she exclaims down the phone later, the hub of the critically acclaimed Italian restaurant bubbling in the background. “People seem to imagine them full of diverse people coming together over their passion for food, when in reality it’s not like that at all.”

Tavolino’s kitchen, far from being the rule, is one of the hard-won exceptions to an industry dominated by white men: “This industry is not remotely representative of the wider community.”

That she can see and hear a diverse range of faces and voices is testimony solely to her and her head chef Louis Korovilas’ hard work and open-mindedness.

“We actively took charge of the hiring and took the focus away from previous skill and experience. We didn’t really pay that much attention to where an interviewee trained, or where they worked; we paid attention to their passion; to what excited them and to what they were interested in learning,” she says. “I made sure we lined up people from a minority background and said, I don’t get care if they don’t have as much experience. Get them in the door and give them a chance.”

Of course, I knew diversity was an issue in the industry in general. Only 11 of those restaurants named as the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list are run by women – despite their apparent attempts to diversify the selection. Earlier this week, a Vice article reported that only two out of 328 UK restaurants reviewed by major British newspapers between January 2019 and January 2020 were black-owned.

Earlier this year, a piece penned by Melissa Thompson for the newsletter Vittles reported that between the Guardian, The Observer, The Telegraph, Financial Times, The Times and The Sunday Times, there have been only two reviews of a restaurant serving African or Caribbean cuisines in the last 10 years. Such glaring omissions have become headline news in the wake of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests – but they are just the symptoms of a problem that has its roots in the same systemic sexism and racism that afflicts all industries which end up predominantly white and male.

“We are the end result of a flow chart that is designed to preserve the status quo,” says Alex Claridge of Wilderness in Birmingham. Though Claridge draws on an eclectic mix of cuisines, the paucity of experienced chefs means he has struggled to make his kitchen as diverse as his menu. Reversing this flow isn’t easy.

With very few races represented either in the kitchen of high-end restaurants or in dining rooms themselves, the issue becomes “a circular one”, he continues. “There aren’t the role models. The inspiration isn’t there.” How on earth do you get chefs of African or Asian extraction through the kitchen door if neither the faces nor the cuisines they are most familiar with are visible at the highest end?

Of course, Ikoyi quickly got labelled as ‘a west African restaurant with a Michelin star’– a misnomer which is in itself revealing

“I think this is changing, but it’s a painfully slow process. There are a few high-end Indian restaurants now” – Tamarind and Benares in London and Pushkar in Birmingham being notable examples – “and Ikoyi is doing interesting stuff with west African ingredients. On the whole, though, European cooking is pretty much the expectation when it comes to fine dining, and that’s a big barrier.”

While we’re prepared to pay above the odds for the drizzles, carpaccios and foams of fancy French cooking, the manifold cuisines of India, the Middle East and Africa tend to be put in the boxes marked “soul food”, “comfort food”, “street food” – and therefore, “cheap”.

The reasons for this are complex: tied to the cost of property in city centres, the fact immigrants have historically settled on the outskirts and been economically disadvantaged, and the fact that “fine dining has historically been the preserve of a certain demographic,” says Claridge.

It can often be seen that those of colour or are an ethnic minority are found in the low skilled areas of the workplace, but they have the ability and talent which should be nurtured and trained

This was all too evident when Ikoyi, a high-end restaurant which draws upon west African flavours, opened in London’s Mayfair and won a Michelin star in 2018. “I had never been in a fine dining restaurant where I was surrounded by other black diners. It blew my mind,” recalls Sessegnon-Shakespeare. “It made me realise the extent to which, everywhere else, the standard customer is white.”

Of course, Ikoyi quickly got labelled as “a west African restaurant with a Michelin star” – a misnomer which is in itself revealing. “Jeremy [Chan, Ikoyi’s co-founder] would be the first to tell you they’re not a west African restaurant,” says Adejoke Bakare of Chishuru. Hers is a west African restaurant, combining the best of British and African produce and modern cooking techniques to bring the cuisine of her homeland Nigeria to Brixton in London; Ikoyi got labelled thus because Chan’s business partner, Iré Hassan-Odukale, is west African and their menu is partly inspired by west African ingredients.

Unlike Chishuru it makes no claim towards authenticity, and Chan and Hassan-Odukale have stressed that time and again. The fact that the qualifier of “African” or “west African” so often gets inserted before “Michelin starred restaurant” when it comes to Ikoyi is “such a shame,” says Sessegnon-Shakespeare. “It’s like it takes away from the achievement. It’s an incredible restaurant with incredible cooking, just like any other Michelin starred restaurant.” Instead, says Claridge, there’s this “weird fetishisation of the pseudo-exotic” on the part of press whenever a fine dining restaurant that isn’t European gets feted.

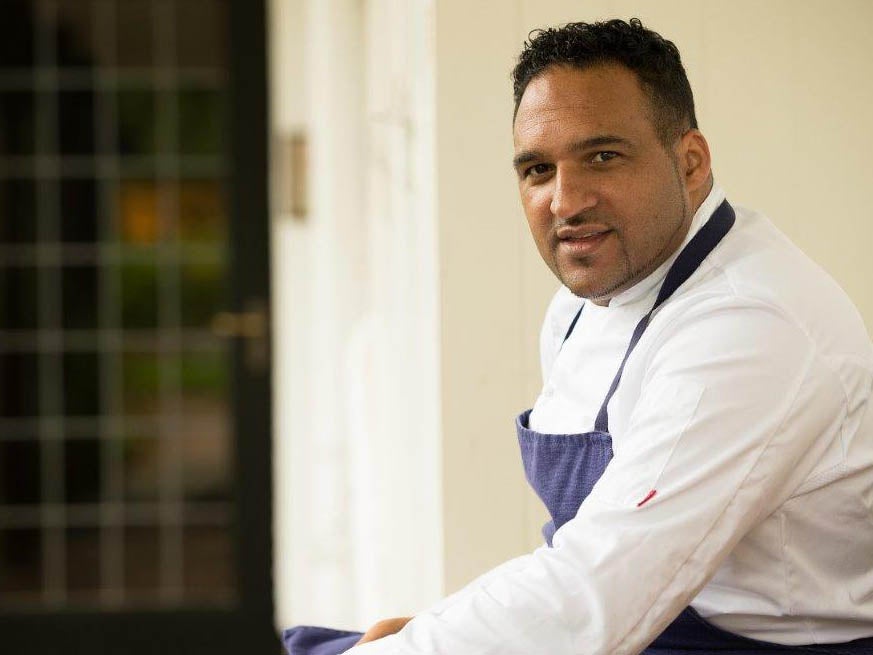

Fortunately, Ikoyi is not the only restaurant whose success suggests Britain’s restaurant scene might be changing – albeit at a speed that is glacial at best. In Exeter, Michael Caines is one of only two black chefs in the country to hold a Michelin star, for his restaurant in Lympstone Manor hotel. Though for many years he shied away from talking about race, the rise of the far right and the notable lack of diversity within his industry has prompted him to speak out. “There are less people of black, Asian and ethnic minorities and therefore there are fewer of us in represented within a workplace and industry to start with, and therefore even less represented the higher you go,” he says. That said, he acknowledges that while “fine dining was once only seen as French haute cuisine, you now find chefs celebrating Asian, Indian and north African influences”.

One of the many barriers entry minorities face is the assumption that they will be more experienced or more comfortable with the cuisine of their ‘homeland”’– regardless of whether or not they were born in Britain

Caines’ own success he owes to hard work and to Raymond Blanc, who saw beyond his skin colour to his talent, graft and determination. One of the many barriers ethnic minorities face is the assumption that they will be more experienced or more comfortable with the cuisine of their “homeland” – regardless of whether or not they were born in Britain. “I think that’s maybe why I went into French patisserie,” muses Sessegnon-Shakespeare. After all, if ever a culinary genre was white and male it is French baking. “There is an element of having something to prove.”

While we will welcome an almost infinite number of English chefs cooking pasta, when Sabrina Gidda (now executive chef at AllBright in London) took the job at Italian restaurant Bernardi’s, people questioned what an Indian girl knew about Italian food. The spurious idea that a cuisine is best cooked by those who are steeped in its heritage is further undermined by Bakare, who has found hiring chefs of west African extraction can sometimes prove more problematic. “I don’t need someone telling me how their auntie or their grandma cooks, telling me I’m doing it wrong!” she laughs. “When I’m hiring, my question is are you willing to do it the Chishuru way, and are you willing to learn.”

Though both Bakare and Sessegnon-Shakespeare have experienced racism within the industry, they have been far more adversely affected by the toxic masculinity still rife in restaurant kitchens. “On the whole I would say being a woman has impacted me more than being black in this industry,” says Sessegnon-Shakespeare. “The restaurant world is still, essentially, a boys club,” agrees Bakare, “and the women that are there tend to want to be in the with the boys – to be part of the pack. There is a bit of vag-blocking.” This is largely because opportunities for women are so limited; because the hours are so punishing, because the chances of a woman staying in the industry post having a family is vanishingly small; and because of inherent bias that “we don’t have what it takes, or don’t have the knowledge”, says Sessegnon-Shakespeare. It’s a bias compounded by the intense environment of restaurant kitchens which, “for lack of a better term, are like pressure cookers. And under pressure people can start acting like a**holes”.

“As a black woman, I know walking into a homogeneous kitchen filled with white men there are going to be problems,” she continues. “Naturally we band to people we see as similar to us. In-group bias is just human nature, and it isn’t a phenomenon that is always sinister and dangerous.”

Add sleep deprivation, burnout, alcohol, drugs and adrenaline to this mixture, however, and this behaviour can manifest itself in more unpleasant, insidious ways. “Somebody, usually myself, is always on the outside, wondering why they’re being treated differently” – whereas when you have a diverse team, as she does now “you force people to bond because of reasons other than ‘you look like me, you sound like me, you act like me’”. Shuko Oda, head chef and co-founder of Koya, a Japanese restaurant in Soho, has “subconsciously leant towards hiring other females in the kitchen and people from different races”.

“Having staff from different races forces our team to communicate in new and fun ways to combat the language barrier, which actually helps our team get to know each other better and become closer,” she observes. “I want to make sure we’re a good fit for London’s diverse community and don’t fall down the male dominance trap that you often find in kitchens throughout the UK.”

If you’re going to hire minorities just to hit your diversity quota and not take on board their experiences, their voices and struggles, then you’re just doing more harm than good

Yet you don’t need to hear about the inner workings of the kitchens to appreciate the value a diverse team brings to a restaurant. “The best example of how culture and backgrounds can influence menus and techniques is simply by looking at the diversity of British cuisine today,” says Caines. “You see there is a variety of cultural influences.”

Look at the menus of those restaurants which do indeed boast a diverse workforce, and you’ll likely find a rich and sumptuous mix of techniques and ingredients. “Our staff cook for each other rotationally at staff lunches and dinners, meaning they can introduce the rest of the team to new flavours and cooking techniques from their home countries,” says Oda. “It’s worked so well that we started to introduce one-off dishes created by our diverse team of chefs to our daily blackboard specials, allowing them to create their own takes on our classic Japanese dishes and express themselves – so we’ve had specials with twists from around the world, including Taiwan, India and Portugal.”

“Knowledge of other cultures and cuisines is what stops our dining out experience being bland and one dimensional,” says Gemma Simmonite, co-founder of Gastrono-me in Bury St Edmunds. A chef of Greek Cypriot heritage she has been determined to “always keep that diversity in our kitchen” and to reflect it in her menu, which draws on cafe cultures from all over the world.

Though Tavolino is an Italian restaurant, Sessegnon-Shakespeare’s inspiration is also international. “The polenta cake we use … was actually developed from a traditional cornbread recipe as my roots go back to the southern states of the US. The execution is similar to that of classic financiers – so via Louisiana and Paris we have an Italian dolce varese on the menu.” Yet employing ethnic minorities in the kitchen and drawing upon their culinary heritage is meaningless, she says, unless one is also invested in looking after them and growing their careers.

“It can often be seen that those of colour or are an ethnic minority are often found in the low skilled areas of the workplace, but they have the ability and talent which should be nurtured and trained,” says Caines.

I am perturbed by Bakare’s observation of “the clear division between chefs and kitchen porters. The porters are usually from minority backgrounds – but the funny thing is, many chefs I have met have heard of [west African spice blend] tsire because their KPs have brought it to the restaurant, and they’ve liked and incorporated it into their food.” To do that at the same time as training and promoting those porters – that is one thing. But to simply “draw inspiration” without giving back seems to be the line between assimilation and cultural appropriation.

“If you’re going to hire minorities and individuals that have been systematically failed time and time again over the course of history you owe them support,” says Sessegnon Shakespeare firmly. “If you’re going to hire minorities just to hit your diversity quota and not take on board their experiences, their voices and struggles, then in reality you’re probably just doing more harm than good.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks