Social media gives young female celebrities a platform Britney Spears didn’t have – but it hasn’t stopped the torture

We might collectively squirm watching archive footage of noughties celeb interviews, but Rachel Brodsky says we shouldn’t kid ourselves that women in the spotlight have an easier time now

There’s a sequence in Framing Britney Spears, the New York Times documentary about the pop star’s conservatorship battle, in which old television interviews conducted during Spears’ early career are cut together. Industry veterans like Diane Sawyer pelt the teenage singer with shaming questions about her breakup with Justin Timberlake, comedians like Sarah Silverman call Spears’s two children “the most adorable mistakes you will ever see”, and presenter Ivo Niehe asks a 17-year-old Spears whether she has had breast implants.

When the documentary was released in February, archive interviews with other female celebrities began circulating on social media. We collectively watched the footage with fresh eyes and nauseated stomachs.

The revered late-night host David Letterman was remembered as a repeat perpetrator of the uncomfortable interview genre, including one in which the former Tonight Show host teased Lindsay Lohan about returning to rehab in 2013; another in which he presses Paris Hilton for details about her time in jail in 2007 [Hilton has recently criticised the interview as “very cruel”] and a bizarre moment from 1998, in which he pretends to eat Jennifer Aniston’s hair. Elsewhere a 2001 interview with Tina Fey focuses not so much on the comedian’s career as it does on how she feels being Saturday Night Live’s resident sexy geek (“Meet Four-Eyed New Sex Symbol”, read one headline).

Are these interviews only uncomfortable with hindsight - seeing them now through the prism of movements like #MeToo - or were they just as bad when they first aired? Should we have seen it then? Framing Britney Spears has forced a major reckoning on the treatment of female celebrities, in particular how we thought of, consumed, and portrayed them in the 1990s and 2000s. But how much has really changed?

Read more: Piers Morgan is gone. Time to admit the truth is worse than the rumours

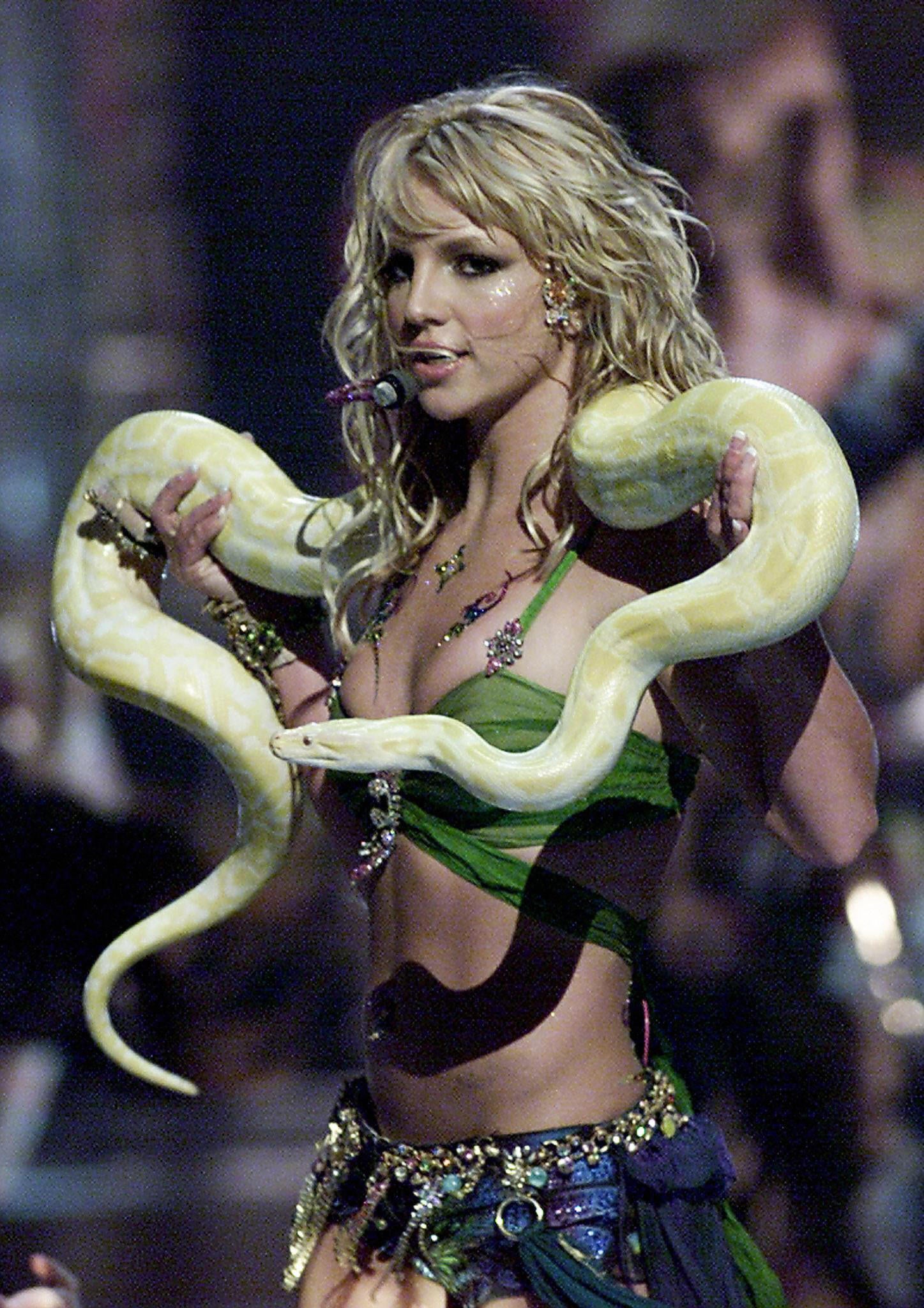

One of the central themes of the documentary is Britney’s public image. She was the archetypal example of a woman who was simultaneously sexualised and angelic. Her management, record labels, and agencies all worked to craft this good girl-gone-bad paradox, to fit a Venn diagram that made parents feel uncomfortable, titillated men, and appealed to but didn’t threaten young fans: the layers of the success to the Britney empire.

Paul McEwan, a professor of film at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, recalls one particular moment that encapsulates this complex narrative. “I always go back to that 1999 Rolling Stone article [where the writer describes] her ‘honeyed thigh’. That moment when she’s super hyper-sexualized, when she’s underage. At the same time, she is insisting that she’s a virgin. And that was important, apparently, that she keep insisting that,” he tells The Independent.

For McEwan, Britney as a product to be sold, has a lot in common with how India has historically marketed its female Bollywood stars. “Women in Indian films, because it’s such a patriarchal society, it’s common for women to do these wet sari scenes. There’s limited sexuality in Indian films, but there are these scenes of feminine display where someone’s dancing in the rain for five minutes. But then the film and the narrative will insist on that her virtue is so important. It’s the same with Britney, where her sexuality is for other people. It’s for men and the audience to enjoy, but she’s not to have any part of it.”

It’s the same with Britney, where her sexuality is for other people. It’s for men and the audience to enjoy, but she’s not to have any part of it.

This lack of agency for Britney is a key tenet of her struggle - infantilised in public [who can forget the schoolgirl video for Baby One More Time] while dealing with being disenfranchised by her conservatorship in private. Today we still see a requirement for young women to be both powerful and inspiring to young fans, but wholesome and deferential enough to be aligned with family values.

Despite being 16 years younger than now 39-year-old Britney, Bella Thorne, 23, an actor and former Disney personality - Britney was a member of the Mickey Mouse Club - commented on her own industry experience, noting: “There [is] definitely a lot of pressure in the Disney eye to be so perfect and I think that’s where Disney in a sense goes wrong because they make their kids seem perfect.” Indeed post-Disney fame in particular is one of the trickiest and most infamous transitions celebrities face.

Another Disney alum, Selena Gomez, 28, has also shared insight into the perilous tightrope you walk as a child in a world of adult stars. "I remember just feeling really violated,” Gomez told Elle magazine in 2017. “I was maybe 15 or 16 and people were taking pictures – photographers," she recalled. "I don’t think anyone really knew who I was. But I felt very violated and I didn’t like it or understand it, and that felt very weird, because I was a young girl, and they were grown men.” Although we retrospectively feel uneasy about Britney’s treatment, it is clear it didn’t end as long ago as we hoped - or even end at all.

But there were certain factors in the early noughties that created a boom period, most notably digital photography. “The change in paparazzi’s equipment from film cameras to digital cameras allowed them to take an infinite number of pictures of celebrities,” says Maura Johnson, a Boston-based pop culture writer and journalism teacher. Suddenly, consumers could see endless photographs of stars going about their daily business, and the pictures sold magazines (titles such as Heat! and Closer later experienced a decline in sales when gossip pages moved online).

Society is well aware of the impact of looking at these images on audiences - a study from 2018 found 58 per cent of 11 to 16 year olds were driven to achieving physical perfection by celebrity culture. But what about the impact on those featured in the images? Former child star Mara Wilson wrote in The New York Times about desperately trying to retain control over her image. Wilson also saw the good-girl-gone-bad paradox at work. “By 2000, Ms Spears had been labelled ‘Bad Girl’. Bad Girls, I observed, were mostly girls who showed any sign of sexuality,” she wrote. “People had been asking me, ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ in interviews since I was six. Reporters asked me who I thought the sexiest actor was.”

Read more: Why we are all suddenly talking about the noughties

And these are just the stories that have been shared. Dr Charlynn Ruan, Los Angeles-based clinical psychologist and founder of Thrive Psychology Group, who treats a number of high-profile women says: “The stories I hear from my clients are even worse than what is talked about openly. The system is so deeply broken that it is almost impossible for there not to be negative consequences [for] women in the industry.

“Some of my clients with reputations for being ‘divas’ or ‘difficult’ are some of the kindest, sweetest, and most respectful people I’ve met. But, once someone in the media labels them as difficult, often based on their looks or them asking for equitable treatment to their male co-stars, it is very hard for them to change that narrative.” The main question Dr Ruan came away with after watching Framing Britney Spears was “I wonder how her life would have been different, had the response of society been one of respect and support?”

So are things different now? Since the advent of social media, celebrities undoubtedly have much more control over their personal narratives - given it does not have to be fed through the media middleman. Society is also having ever greater conversations around mental health, body image, and the abuse of power often seen in male-female dynamics. Even so, an insatiable need for content remains. And the women in front of the camera are every bit as susceptible.

One positive change is that there is less tolerance for reporters to say openly sexist things but the bar was so painfully low

McEwan has noticed that just because female celebrities can shape their own narratives on social media, and are less reliant on positive press commentary, it hasn’t ended the persistent negativity and criticism that stars like Britney experienced over 20 years ago. “In some of those cases that have gotten really harassing or, there’s this sense that if you want to be on Twitter, that’s just what you have to put up with,” McEwan says.

But some things have improved - namely that society is less tolerant of certain aspects of reporting. Dr Raun says: “One positive change is that there is less tolerance for reporters to say openly sexist things to celebrities,” but she adds, “the bar was so painfully low, we have a very long way to go.”

The feedback loop that social media provides has also changed the dynamics of media coverage. For example, when Page Six posts photos of Billie Eilish in a tank top, inviting us to gawk at her figure, the outlet is overrun by social media commenters with accusations of body shaming. Likewise, when body shamers started on Lady Gaga for her appearance at the 2017 Super Bowl, she shot back: “I heard my body is a topic of conversation so I wanted to say, I’m proud of my body and you should be proud of yours too.

Dr Raun says: “The rise of the internet in the last 20 years has brought with it good and bad consequences for women in the public eye. I do a lot of work with clients on developing strategies for managing the negative impact of painful and cruel words on the internet.”

Read more: Demi Lovato says she was sexually assaulted in 2018

It would be easy to assume that because celebrities are in control of their own narratives via social media, the problematic way we treat female celebrities could have fizzled out. But the patriarchal, conservative values remain, even in 2021.

Where Britney was forced to contend with hoards of paparazzi trailing her every move in the 2000s, today’s celebrities have to put up with endless bullying comments on social media and — as we recently saw in Meghan Markle’s interview with Oprah Winfrey — tabloid headlines and clickbait.

Ultimately, while the power may be increasingly in the hands of celebrities, the media is still hungry for content and as long as talent can be commoditised, it’s unlikely that things will change as much as we need them to.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments