Labour has never enjoyed a wider field of candidates for leader – but there are problems ahead

From Rebecca Long Bailey and Ian Lavery possibly splitting the leftist vote, to the fact nobody has yet captured the public’s imagination – this leadership election will not be simple

Many men (though, as yet, no women) have led Britain’s Labour Party. They varied a good deal in their background and personalities. Some were educated at public schools and Oxford (Blair, Gaitskell); some left school in their teens (MacDonald, Callaghan); they came from Scotland (Brown, Smith), Wales (Kinnock) the north (Wilson) and the south (Attlee, Corbyn, Lansbury, Miliband). They emerged from every class, bar the aristocracy.

Some were more successful than others (only three managed to win a Commons majority), but they and their beliefs were not defined solely, or even principally, by whence they came or which boxes they ticked. That is not what politics is all about.

One of the few signs of hope in the Labour leadership election is that the early demands that the next leader has to be female, or have a northern accent or be working class or all three, has faded. (The fact that the man who won the 2019 election has the background he has and went to Eton might have helped quash that argument). Labour has started to look instead at the ideas, the policies and the techniques that failed so miserably only a few weeks ago. That’s progress.

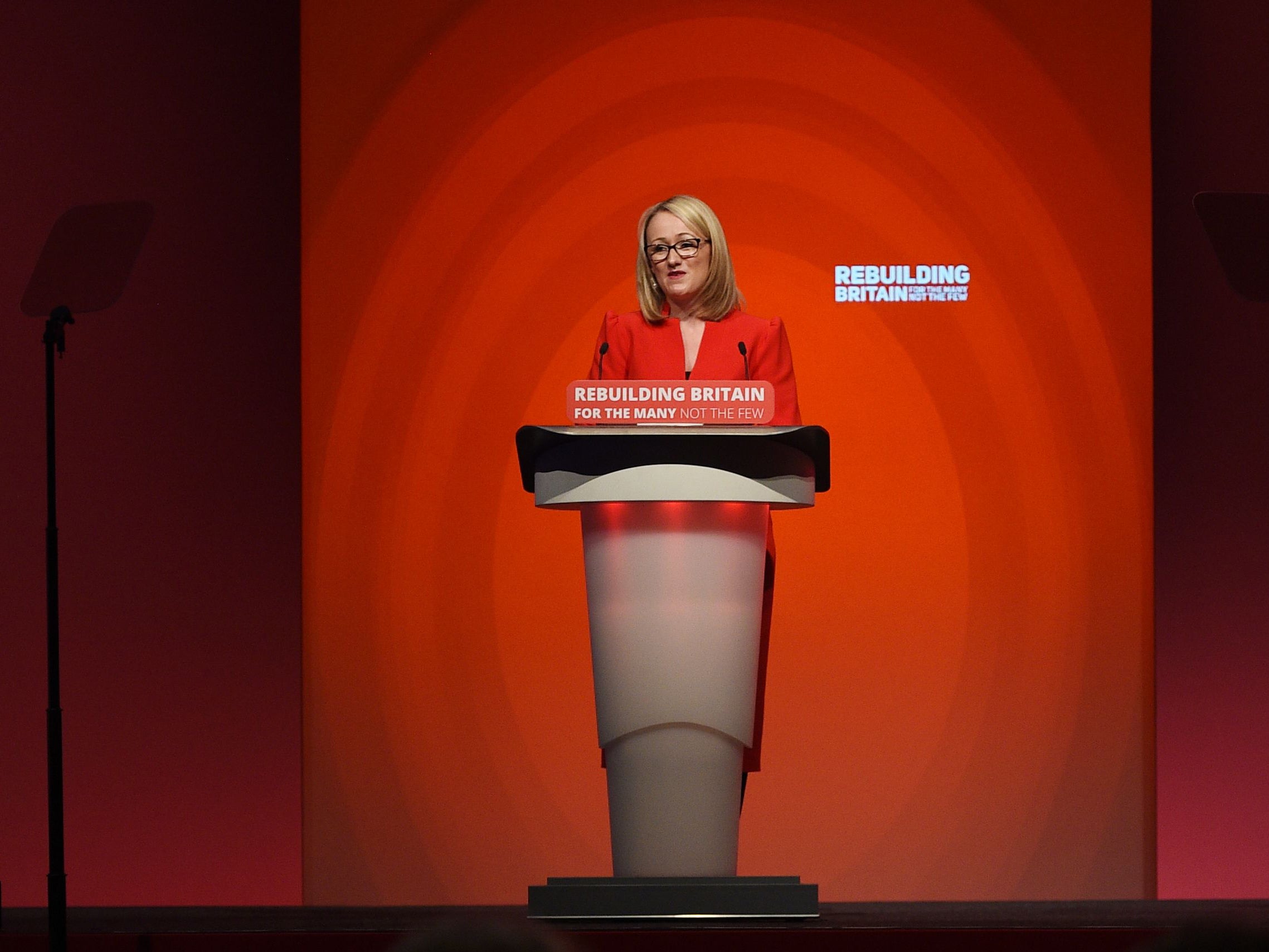

But as yet, the examination remains cursory. Rebecca Long Bailey plainly wants to be regarded as something more than Magic Granddaughter, the continuation of Corbynism by other means, so authentic that tall-tales have done the rounds that she was practically born on the pitch at Old Trafford during a match against Chelsea.

Ms Long Bailey has come up with something called “progressive patriotism”. As a mildly coded rebuke to the excesses of the Corbyn era it has promise, but it is ill-defined at best. Indeed, Ms Long Bailey seems still nervous about going too far too fast in abandoning her mentor and patron Mr Corbyn. “We didn’t lose because of our commitment to scrap universal credit, invest in public services or abolish tuition fees,” she argues. Perhaps not, but the public did not think Labour could achieve those things; and the party that promised to keep universal credit, tuition fees and only invest in limited ways in the public services, those Tories, won 3.7 million more votes than Labour. Ms Long Bailey is yet to explain why Labour did lose and, more to the point, how it can win next time. Indeed, she is yet to say she is actually running, though she seems happy to put Angela Rayner up for the deputy job. It doesn’t look politically skilful or decisive.

Even so, RLB, as we may learn to call her, is veering too far from Corbynite orthodoxy for some, including party chair Ian Lavery. Obscure even by current Labour front bench standards, Mr Lavery is probably best known for his rich Geordie brogue and for losing the last general election. If Labour concludes that nothing much went wrong last time, he’s their man.

Clive Lewis, again not yet a household name, is bolder in arguing that Labour ought to have mirrored what the Conservatives did with the Leave vote and tried to scoop the Remain vote. Labour might, indeed, have done better and been truer to its members’ beliefs if it had (here, on Europe, Mr Corbyn and the Corbynites of Momentum tend to part company).

In terms of choice, in background and outlook, Labour has never enjoyed a wider, richer field, also including, with varying prospects: Richard Burgon, Keir Starmer, Jess Phillips, Emily Thornberry, Lisa Nandy, Yvette Cooper, David Lammy and Dan Jarvis. There are enough for a football team. At the moment, none have set out anything like a path to power, and most are speaking in riddles. None has yet captured the public’s imagination. A case of more candidates, less choice, then, which is the one thing Labour doesn’t need.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments