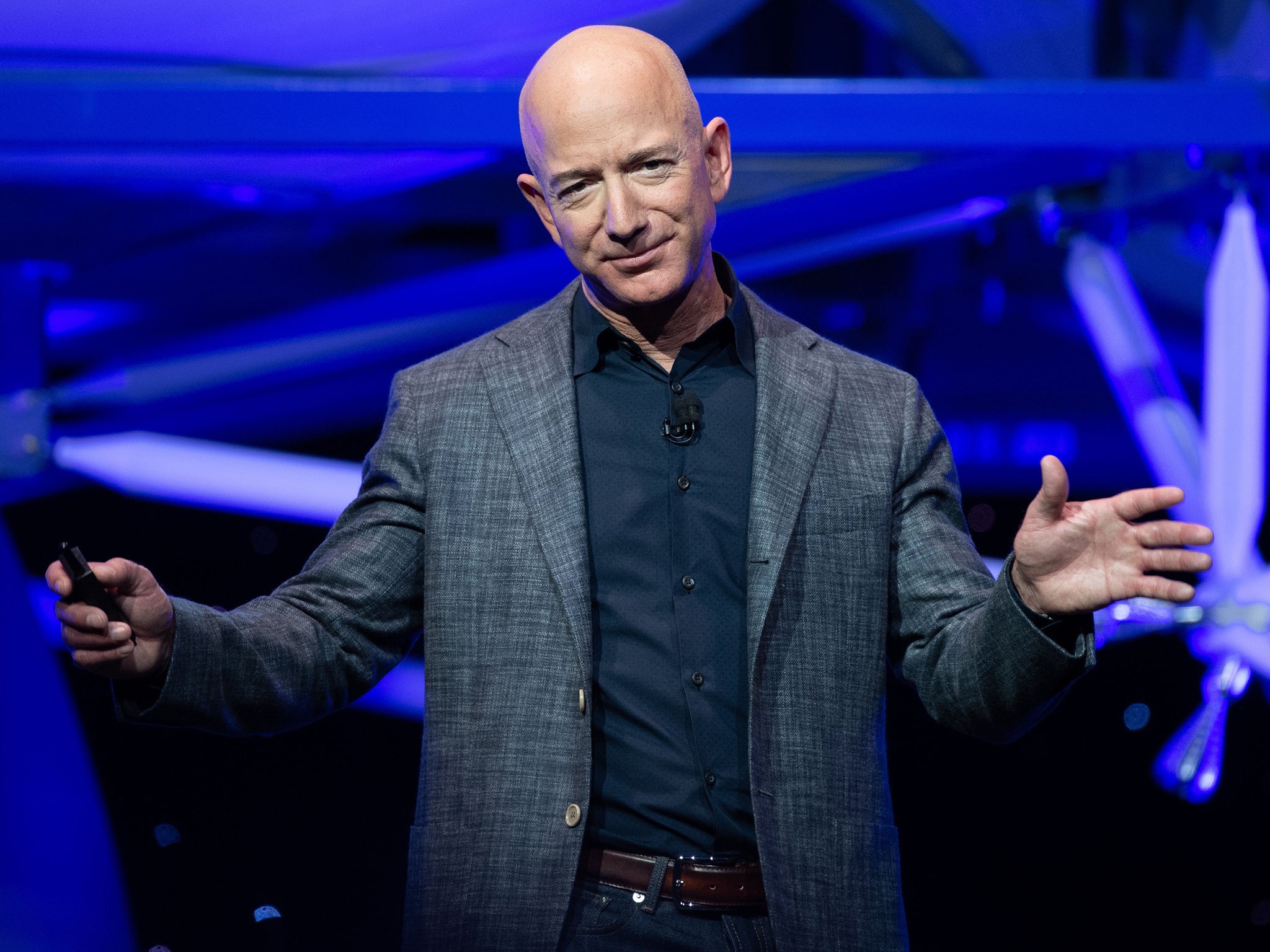

Jeff Bezos: What will the billionaire do after Amazon?

Now that Bezos has plenty of free time on his hands, could he be on track to win the brewing space race? Sean O'Grady finds out

Imagine, if you can, in a pre-Covid world, wandering into a highly exclusive cocktail party populated by some of the wealthiest people on earth. Mostly male, but you’d easily spot the Queen in there, maybe chatting over a Dubonnet and gin with the only other female in the room, Alice Walton, heiress of the Walmart fortune. Some distance away, conspiratorially in a corner there might be Donald Trump, Diet Coke in hand, Silvio Berlusconi and Rupert Murdoch. The Duke of Westminster, owner of much of central London, has caught the interest of Sir Paul McCartney. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor, might be dispensing sage advice to Lionel Messi, David Beckham and Cristiano Ronaldo about their nest eggs.

Quite the gathering, but if you sneaked away to do a little googling you’d soon discover that, loaded as they all are (the Queen would actually be the poorest attendee), if you put all their assets together, and give or take the odd billion down the back of a settee, their combined net worth is less than that of Jeff Bezos, technically still a bloke who works at Amazon (though given that he still owns 10 per cent of it, it might better be said that Amazon works for him).

Bezos’ share of the $1.6 trillion (£1.2 trillion) Amazon is worth as a quoted company outweighs the lot of them. Alongside Elon Musk, usually ranked at the top of the rich lists, Bezos is either the richest person on the planet, or else narrow runner-up. Bezos, by the way, points out that because he has sold 82 per cent of his shares over the years, he and his companies have also enriched many more shareholders and pension funds.

Still, who’s counting? Bezos always claims that be never set out to become quite as loaded as he’s become, though the progress he’s made from the $300,000 (£216,000) his parents gave him to start an online book store nearly three decades ago has proved a decent enough punt. His fortune, and how he came by it, is the most remarkable fact about Bezos, indeed the defining one. It is not, though, the most interesting or revealing thing. That’s his funny laugh.

Now that he has stepped back from his full-time role as chief executive of his baby turned tech giant, there’s been quite a bit of coverage about him. His new vision of interplanetary travel and space exploration is stirring stuff as he retails it, and, like his rival Musk’s parallel ambitions, it grabs the attention. Not, however, as much as his laugh, which has been heard quite a bit on the airwaves lately as he’s been in the news so much. Perhaps befitting his glabrous appearance, he sounds very much like a performing seal when something tickles his ribs, which happens quite a lot. It’s an almost alien, disruptive noise, part-honk, part-bark, part-Dr Evil (and he does bear a passing resemblance to Mike Myers’ comic creation). There are more centi-billionaires on earth than people who laugh like Bezos.

He is conscious of it. He’s always had it, and it’s caused some inconvenience. A dedicated swot, he once lost his school library privileges because of it, and he’s revealed there was a “multi-year period” in his adolescence when his younger brother and sister wouldn’t go to see movies with him because it was so embarrassing. “I laugh easily and often,” he’s explained in interviews; “Anyone who knows me well will say, ‘If Jeff’s unhappy, wait five minutes.’” Bezos explains it like this: “I can’t maintain unhappiness. Maybe I have good serotonin levels or something”.

Of course that happiness isn’t quite the same as jollity or generosity of spirit. He is not especially generous to his Amazon family, is hard on underperforming associates, and he is a driven, focused man. So focused indeed that he is incapable of multi-tasking, so he can’t, say, have dinner and the occasional glance at his emails. At his Montessori school, his teachers had to lift him from one desk to another when the time came to change task. (His formal education began, by the way, at the age of two.)

Bezos, despite the smart-casual apparel and relaxed, smiley public demeanour, is far from easygoing. Every day, he says, is “Day 1” at Amazon, the slogan supposedly inspiring his half-million employees with a spirit of exploration. Having rejected the odd, made-up, word “Cadabra”, Bezos’ original idea for the name of his new online bookstore back in 1994 was “Relentless”, which sums things up much better – there was always a wider ambition at work there.

Bezos is not smart enough to avoid all trouble, however, even the trouble that is avoidable; but he is smart enough to survive it

Bezos’ happiness, really a sort of contented restlessness, is more an outward expression of a man at ease with himself, nerdy as it is. He has the confidence, and nowadays experience, that his particular kind of intelligence will not only see him through most problems, but far transcend them. He believed it when he was a nobody who decided to work for himself, and he knows it for certain now. Bezos sometimes observes that there are many kinds of “smart” (adding that there are also many kinds of stupidity), and he learned the nature of his own towards the end of his time as a gifted computer science and electrical engineering student at Princeton in the early 1980s.

Having always been academically high-achieving and an alpha-plus student, Bezos and a friend one day became stumped on a particularly tricky partial quadratic equation. After some hours of frustration they made off to find the cleverest person on the campus who solved it, immediately, on paper within minutes, based on some remembered insights from a similar resolution some years before. Gazing at the perfectly laid-out workings of the campus genius, Bezos concluded there and then that he wasn’t going to be one of the top theoretical physicists in the world, and adjusted his sights accordingly. After a short time at a telecoms start-up he went into banking and joined a small, at the time, hedge fund in New York, DE Shaw. Dave Shaws’ approach was an early example of data-driven banking. Bezos fitted right in, and evidently learned a lot about business there. He combined this with an intense interest in the nascent world wide web, and a certain amount of imagination and brains to create his vision of online commerce.

According to Bezos he “fell in love with computers in the fourth grade”. He’d first been exposed to them via a mainframe that his school had access to, a rarity in the 1970s. He soon started to get the hang of the crude modem, paper ribbons punched with holes and elementary programming which “we taught ourselves”.

Books were chosen by Bezos for his virtual store because it was the category of merchandise with the largest number of items – there being far more books in print than could possibly be housed in even the biggest book store. It was the ideal area to get into. So Bezos quit his comfortable job on Wall Street, tried and failed to explain to his parents what the internet was – though they backed him – then loaded his belongings into his Chevrolet Blazer 4x4 and drove to Seattle. The business plan was written en route. He went to the west coast because there he knew Bill Gates and Microsoft were based there, and he might find the necessary skilled people to make his venture successful.

He’d been wed for only a year to MacKenzie Scott Tuttle, an English student he’d met at Princeton. In the early days, she did much to establish the embryonic empire, arranging the accounts and negotiating contracts. They were engaged on the classic tech start-up – parcelling up books on the floor of the garage. In those days they dreamed of having enough money to buy some packing tables. The first sale, on 3 April 1995, online of course, was a copy of Fluid Concepts and Creative Analysis by Douglas Hofstadter.

Bezos, in that breezy west coast way of a tech guru, likes to dismiss the idea of a work-life balance as a false choice

Bezos’ smartness, indeed brilliance, initially lay in being able to intuit the business opening and the wider opportunity it represented. Soon, of course, Amazon moved into selling music (CDs), DVDs, toys, hardware... until it became the “everything store”. Third parties were invited on to Bezos’ wholly-owned digital high street in 2000. A few years later came streaming services, downloads and the phenomenal Prime, now with 150 million subscribers. There was also the ebook revolution and the Kindle, the Echo and Alexa; Amazon Web Services; Amazon’s advertising business, Amazon Studios, as well as acquisitions of Whole Foods, The Washington Post and of course the creation of Bezos’ space division Blue Origin, his grandest project of all.

The key to these successes is not just the sort of fashionable management newspeak that Bezos comes out with. Rather it is also about in getting the consumer, knowingly or not, to help Bezos develop his products and, thus, make his business even bigger: that’s smart. Thus, from the earliest days when it was possible, the software would start to detect customers buying habits and preferences, which would then be used, as is familiar now, to suggest and nudge them toward other products or services. Early attempts were crude, but, thanks to the constant interaction with buyers, the algorithms became more accurate and useful to both sides of the bargain.

However, Amazon was accused of gathering data about its third party “partners” to steal their customers for itself, or use the information and threat to leverage better deals from other suppliers. When, controversially, Amazon offer police forces the use of early face recognition technology, called Amazon Rekognition, the officers and the law enforcement agencies are also helping Amazon hone the software to make it into a market-leading product (and thus early dominance of yet another emerging market). By the same token, too, knowing the way people variously behave towards their Alexa devices helps Amazon make them more responsive and useful. They do this through an even more sophisticated method of machine learning, artificial intelligence.

It is this technology, still in its infancy, that might well transform call centres, a low-skilled service occupation, and possibly rudimentary medical diagnoses in the same way that information technology, digitisation and robotics have changed manufacturing, retail and the media forever. The customer gets the benefit of lower crime rates and even easier access to products, entertainment and information, but Bezos gets the profit.

Bezos is not smart enough to avoid all trouble, however, even the trouble that is avoidable; but he is smart enough to survive it. His marriage to Scott ended in an apparently amicable divorce in 2019, possibly smoothed by a $36bn (£29bn) divorce settlement that immediately propelled MacKenzie to become the fourth richest woman in the world. By then a successful novelist and businesswoman she is now also a philanthropist. They had four children.

Bezos’ extramarital affair with Lauren Sanchez, a television presenter and now his partner, was breathlessly revealed by the National Enquirer in lurid terms, thus: “Bezos has been whisking his mistress to exotic destinations on his $65m (£47m) private jet, sending her raunchy messages and erotic selfies – including one steamy picture too explicit to print here”. The question arose as to how the National Enquirer knew, and what they wanted from their story. Bezos suspected, it seems rightly, that his personal iPhone X had been hacked. The suspicion, supported right up to UN special rapporteurs involved in the case, was that it was Saudi Arabian interests behind the exfiltration of large amounts of Bezos’ personal data. The Saudis and the Enquirer were accused by Bezos himself of trying to influence or blackmail him into restraining The Washington Post’s coverage of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, Saudi dissident and columnist of The Post, at which Bezos was by that point the proprietor.

Extraordinarily the hack reportedly might have resulted from a WhatsApp message sent to Bezos by Mohammad bin Salman, crown prince of Saudi Arabia. One way or another, Bezos emerged from the incident unscathed. He was similarly left apparently unharmed by the attacks on him by Donald Trump, who also disliked The Post’s coverage, calling him “Jeff Bozo”, one of his less catchy nicknames. Apparently, he’s had a couple of conversations with Trump, but he’s keeping them to himself. Spiteful as ever, Trump made sure the $10bn (£7bn) Department of Defence crowd computing contract went to Microsoft.

The general impression left from these controversies is that Bezos is a staunch defender of a free press, and his ownership of The Post seems a model one. He freely paid the asking price the Graham family wanted for it in 2013, $250m (£180m), and did no due diligence. Editorial interference is something he would find “demeaning” and “icky”. He also owns the most expensive mansion in DC, the better to entertain, engage with policymakers and defend his business interests. Privacy concerns about face recognition and Alexa “listening in” on householders or being hacked to spy on households seem to have been brought under control.

His critics, and there are of course very many, say he is more than relentless – ruthless too. They cite his occasional temper tantrums, apparently known as “Jeff’s nutters” among those who work with him. He is said to be a demanding boss. His companies have suffered much abuse over their treatment of suppliers, who complain of being squeezed mercilessly in return for access to Amazon platform. Famously, or infamously, Bezos once advised his executives to suborn smaller competitors as a cheetah would go after the weakest gazelle in the herd – predatory capitalism at its most literal. Low pay and arduous conditions, particularly in the warehouses, or “fulfilment centres” as they’re known, are other grievances.

Bezos, in that breezy west coast way of a tech guru, likes to dismiss the idea of a work-life balance as a false choice. To him, having success at work means harmony at home, and vice versa, the satisfaction gained in both harmoniously mixing and blurring. Someone on modest pay being monitored virtually step by step in some vast inhuman warehouse dodging the robots might not see life that way. Amazon is not especially keen on trade unions, and once walked away from siting its second HQ in New York when local politicians started demanding stronger employee protections.

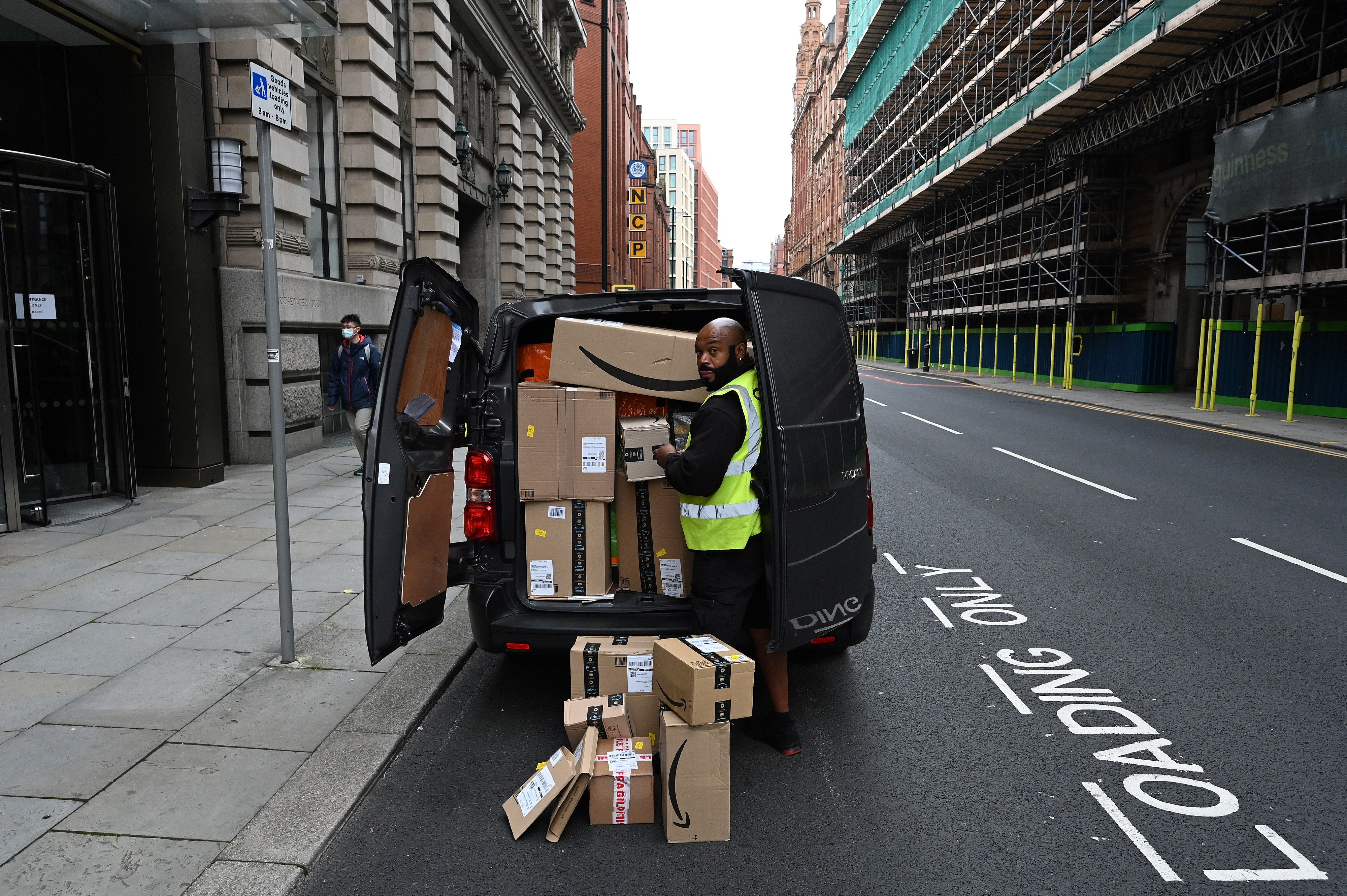

Delivery drivers, regarded as independent contractors, arguably come off even worse than the other manual workers. The default setting for any populist politician is to call for Amazon to be broken up because it is “too big”. Amazon’s image has become steadily more tarnished the more it has succeeded, and Bezos’ reputation with it. As Bezos often remarks, referring to Trump, no public figure can escape scrutiny, and he himself will still be under attack even as he crabs away from day-to-day control of Amazon.

The odd thing about that debate is that it misunderstands the nature of Amazon. It is not a monopoly, because there are still many other retailers around to choose from, and competition is fierce. It lacks market power over consumers, who can go elsewhere if they want. Usually, monopolies are busted because they are caught trying to keep prices high; Amazon has been responsible for reducing prices, increasing market transparency and, debatably, raising product standards and customer satisfaction, always said to be the overriding “compulsive obsessive” concern by Amazon - customer “ecstasy” as it has been absurdly defined.

It is less a monopolist than a monopsonist, a dominant buyer within some market segments, where it uses its heft to drive costs down and pass at least some of that on to consumers. That is very harsh on suppliers, and on producers (including authors), but not on end consumers. It is not so very different in that regard to any big retailers down the ages, including the large supermarket groups of today. Amazon is also a weak presence in South America, India and China, to name a few major growth markets, where local rivals far outsell it. If Bezos has made a lot of money for himself, has he not also put a few dollars into the hands of his customers as well, who can buy a book for 1p plus postage?

Your correspondent, his Dyson finally worn out, recently purchased an Amazon Basics “own brand” vacuum cleaner, which was as powerful, lighter and cheaper than the competition. No complaints there, though its fair to add that Amazon has been accused of selling shoddy or dangerous stuff from third parties. It is also true that Amazon usually pays very little tax on its earnings, making the most of weak international cooperation over tax avoidance. For that too Amazon has become a bete noire for the left, and Bezos with his unimaginable wealth, a man the politicians live to vilify. Yet that case for Amazon’s contribution to our modern standard of living is rarely heard, drowned out by the anguished, and no doubt genuine, groans of hurt from hard-worked staff.

It doesn’t help Bezos, or Amazon, that it “had a good pandemic”, as you might say. The boom in e-commerce and home deliveries during lockdown helped the company to a 44 per cent annual rise in sales, with revenues reaching the $100bn (£72bn) barrier in the third quarter of last year alone. Amazon is shifting something like $11,000 of sales every second, and dropping 3.5 billion parcels with a smiley logo every year.

You might take the view as well that the likes of Musk and Bezos are merely playing with space rocket toys, the centi-billionaires suffering a mid-life crisis in the way lesser mortals might buy a sports car or powerful motorbike

Amazon Web Services (AWS), the cloud computing arm of the organisation, is the real profit driver, and the 100 million Zoom calls made every day by remote workers, all hosted by AWS, were also good for business. Everyone from the CIA to Royal Dutch Shell to Netflix to the NHS stores its data in AWS server farms, and it’s still a fast-growing business. So Covid, albeit unintendedly, probably made Bezos another £36bn richer. To the extent that office work and shopping has moved further online and permanently, Bezos is going to be better off. But imagine a pandemic response where people couldn’t work at home or have their goods delivered – that would surely have cost lives.

The other facet of Bezos’ particular species of smartness is his self-styled resourcefulness, a mix of self-reliance and inventiveness. This sprang, accidentally enough, from his family background. He was born in 1964 Jeffrey Preston Jorgensen, son of a high school student Jacklyn, “Jackie”, Gise, shortly after her 17th birthday. His father, Theodore “Teddy” Jorgensen, was of Danish immigrant heritage a few generations back. Jackie and Teddy were married, but things didn’t turn out for them, and by the time Jeff was four his mum had remarried. This was to Miguel, or Mike, Bezos, who had arrived as a refugee from communist Cuba only in 1962, speaking no English. He eventually ended up in New Mexico where he met Jackie. Jeff took his stepfather’s surname, and Mike then had two more children, Mark (b1969) and Christina (b1970).

Mark and Christina are involved in the Bezos charities. Mark is a volunteer foreman and has appeared on stage with Bezos, and makes Jeff laugh even more loudly and frequently than usual. Christina married a chap by the name of Stephen Poore, thus becoming Christina Poore and gaining a highly ironic surname. The family still see much of each other, but Jeff had no contact with Teddy, and never met him before he died a few years ago. He couldn’t see much point in it, apparently, and Teddy had no idea that his baby boy had become one of the richest people in the world while he was running a bicycle shop in Arizona (no doubt itself under growing pressure from Amazon). Teddy died in 2015, aged 71, and had no other children.

But it was Jeff’s maternal grandfather, Preston Gise (hence the middle name), who seems to have had the biggest influence of anyone. Jeff and his siblings grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico and Miami, but spent every summer for about a decade, from when Jeff was 4 through to 16, on Preston’s ranch in West Texas, some 25,000 acres of it, where they would sound their time exploring the wide open empty rugged landscapes and fixing everything from bulldozers to windmills and performing minor surgery on injured cattle. Bezos was obsessed with science fiction and Star Trek from an early age, and the urge to explore “strange new worlds” might well have been further stimulated by finding ever deeper caves to clamber down into. When he graduated, naturally, as the top student at high school he concluded his valedictory speech declaring: “Space, the final frontier: Join me there!”

That was when he was 22. Now he has the means to make his dreams come true. Bezos’ fame helped him get to be an extra in the 2016 film Star Trek Beyond, fully made up and quite unrecognisable as some sort of scaly alien. It is a bit too fanciful to suppose that he decided to make such unimaginable sums of money here on earth just so he could build his very own version of the Starship Enterprise, but he is certainly at liberty to do so now. It is on this project that Bezos will now devote most of his energy and financial resources to, with The Post and the campaign against climate change also in the mix as he winds down his close involvement with Amazon.

His charitable giving has been increasing, but there is a wider point here about all the billionaire philanthropy’s and their foundations; would it not be better if they paid more tax and democratic governments determined how to allocate these huge resources, rather than the personal tastes of a few rather fortunate and unaccountable men and women. You might take the view as well that the likes of Musk and Bezos are merely playing with space rocket toys, the centi-billionaires suffering a mid-life crisis in the way lesser mortals might buy a sports car or powerful motorbike. They are wasting their own money, but some would argue, also squandering scarce resources that could be put to better use, alleviating poverty, say, or rebuilding Yemen, rather than going for a joy ride to the mesosphere pretending to be Spock.

Bezos has been selling around $1bn (£719m) of Amazon stock a year to fund his Blue Origin company – “incredibly important work that needs to be done as soon as possible”. Its first steps are comparatively limited and realistic – space tourism. A mission to the Moon in 2024 is planned – the first humans up there since Gene Cernan on Apollo 17 in 1972. Could they even be permanent inhabitants? The way Bezos proposes to make his space future work is by inventing reusable spacecraft, with some trials proving promising. The analogy is with your holiday flight (Covid permitting) to say Spain, and imagining how expensive it would be if the plane was binned on the way out and again on the way in.

Even so, how such energy-intensive travel can be reconciled with protecting the planet is unclear. For his part, Bezos is thinking centuries ahead, where the human race would run to a trillion people (just the 7.6 billion now), a wonder race with 1,000 Einsteins and 1,000 Mozarts. The earth itself would be preserved as a place of habitation and nature; heavy industry and mining would be shifted to other planets, and people would live in huge climate-controlled spacecraft, as permanent colonies and self-contained worlds. To Bezos, it is the only way to reconcile economic growth and rising standards of living for humanity and save the planet. The alternative is “stasis”, which would be in Bezos’ view impractical and cruel. It’s all very Arthur C Clarke, and you might think it a bit cranky, and laughable, but then again you might well have said the same in 1994 about the Amazonian world of Alexa and robots that we inhabit today. And look who’s laughing all the way to the interplanetary bank.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments